Raid on Havre de Grace

The Raid on Havre de Grace was a seaborne military operation that took place on 3 May 1813 during the broader War of 1812. A squadron of the British Royal Navy under Rear Admiral George Cockburn attacked the town of Havre de Grace, Maryland, at the mouth of the Susquehanna River. Although the raid resulted in just one American casualty, it catalyzed widespread hatred of Cockburn by the Americans.

| Raid on Havre de Grace | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of 1812 | |||||||

During the War of 1812, British naval forces attacked Havre de Grace, Maryland which showed resistance from the townspeople and Maryland Militia. After the British defeated them they plundered the town at will until withdrawing back to their warships. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Royal Navy |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

George Cockburn John Lawrence George Augustus Westphal | John O'Neill | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

150 Royal Marines Royal Regiment of Artillery Seamen | Fewer than 40 Maryland Militiamen | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1 wounded[1] | 1 dead | ||||||

Background

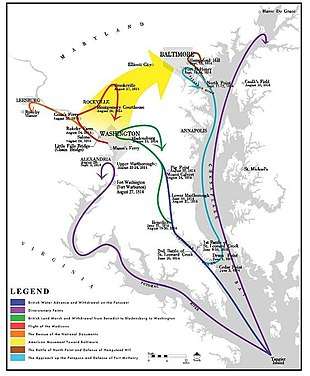

Cockburn sailed for the upper Chesapeake Bay from near Baltimore and occupied Spesutie Island on 23 April 1813.[2]:25–27 After a successful raid on Frenchtown on the Elk River on 29 April, Cockburn attempted to venture further upriver until forces at Fort Defiance stopped him.[2]:27–29 [3]

Cockburn had vowed to destroy any town that showed resistance. The admiral had not initially planned to attack Havre de Grace but when he saw an American flag flying over the town and the local battery fired shots, he decided to attack.[1][2]:27, 29

Attack

Cockburn's fleet was anchored off Turkey Point, separated from Havre de Grace by an area of shoal water too shallow for large ships to navigate.[2]:29 Cockburn therefore sent Commander John Lawrence at the head of a flotilla of sixteen[2]:29 or nineteen[3] boats to row across the shoals, beginning at midnight on 3 May.[1]

Despite or because of intelligence warning of an impending attack, most of the militia that had been in Havre de Grace had departed before the raid.[2]:30 Fewer than forty[3] troops remained at the Concord Point battery when the flotilla attacked at dawn. These troops briefly returned fire until a Congreve rocket killed a civilian.[2]:30 Lieutenant George Augustus Westphal then stormed and captured the battery.[3]

Second Lieutenant John O'Neill single-handedly manned another battery—the so-called "Potato Battery"—until his cannon's recoil struck him.[2]:30 O'Neill retreated to fire on the British with a musket while he unsuccessfully signaled the militia to return.[2]:30–31

The townspeople and remaining militia retreated as Westphal and his troops drove them further from town.[2]:32 The British looted the town and burned 40 of its 60 houses. They spared the Episcopal church from being burned but they did vandalize it.[2]:32 Cockburn removed six cannons from the town and took O'Neill and two other Americans back to his flagship, HMS Maidstone. However, Cockburn released O'Neill upon appeal from local magistrates.[2]:34 Cockburn reported only one injury: Westphal was shot in the hand.[1]

After the raid on Havre de Grace, Cockburn sent troops up the Susquehanna River to destroy a depot and vessels there. Forces also navigated to nearby Principio Furnace, a large ironworks and cannon foundry, and destroyed the facilities there.[1][2]:34

Accounts

Cockburn's account of the raid appeared in the London Gazette on 6 July 1813.[1]

Jared Sparks—an educator, historian, and later president of Harvard University—who was tutoring the children of a local family also saw the attack. Sparks wrote an account of the attack that was published in 1817 in the North American Review and Miscellaneous Journal.[4][5]

James Jones Wilmer was living in Havre de Grace at the time and published an account of the incident soon after it happened.[6]

Benjamin Henry Latrobe did not witness the event but is known to have written to Robert Fulton about it.[2]:32

The raid was depicted in a near-contemporary etching by William Charles, a Scottish-born engraver who immigrated to the United States. The etching, Admiral Cockburn Burning & Plundering Havre de Grace, is now held by the Maryland Historical Society.[7][8]

See also

References

- "No. 16750". The London Gazette. 6 July 1813. pp. 1331–1333.

- George, Christopher T. (2000). Terror on the Chesapeake: The War of 1812 on the Bay. Shippensburg, Pennsylvania: White Mane Books. ISBN 978-1-57249-276-9.

- Malcomson, Robert (2006). Historical Dictionary of the War of 1812. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. pp. 241–242. ISBN 978-0-8108-5499-4.

- Adams, Herbert B. (1893). The Life and Writings of Jared Sparks: Comprising Selections from His Journals and Correspondence. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company. p. 65.

- "Conflagration of Havre de Grace". North American Review and Miscellaneous Journal. 5 (14): 157–163. July 1817. JSTOR 25121304.

- Wilmer, James Jones (1813). Narrative Respecting the Conduct of the British from Their First Landing on Spesutia Island till Their Progress to Havre de Grace ... By a Citizen of Havre de Grace. Baltimore: P. Mauro.

- Lanmon, Lorraine Welling (1976). "American Caricature in the English Tradition: The Personal and Political Satires of William Charles". Winterthur Portfolio. 11: 1–51. JSTOR 1180589.

- "Admiral Cockburn Burning and Plundering Havre de Grace on the 1st of June 1813". Maryland Historical Society. Retrieved May 7, 2011.