Siege of Fort St. Philip (1815)

The Siege of Fort St. Philip was a battle taking place during the ending of the War of 1812 between a sizable British naval fleet attempting to sail the Mississippi River by force in order to provide reinforcements to British forces already attacking New Orleans as part of the Louisiana Campaign, and the single American garrison of Fort St. Philip guarded by a far numerically-inferior force. The siege lasted from January 9 to January 18, 1815.

Background

The Royal Navy had begun the Louisiana Campaign to capture New Orleans. However, to reach New Orleans, the destruction of the small U.S. Navy squadron in the area and the U.S. Army forts and batteries was necessary. Fort St. Philip, an irregular work guarding the Mississippi River, the body of a parallelogram, was one of the said forts.

The fort mounted twenty-nine 24-pound cannons, two 32-pound cannons, and two howitzers, an 8-inch and a 5.5-inch. One 13-inch mortar and another 6-pound cannon were also used. Thirty-five pieces in all were used. The Americans had 163 infantry, 84 white and freed African-American militia and 117 artillery men to man the fort's armaments.

In December 1814, American forces were warned of an approaching British flotilla off Louisiana. This encouraged the garrison of Fort St. Philip to begin constructing better defenses such as a battery on the opposite side of the Mississippi, which would support the two said 32-pound cannons and the 18-inch mortar; the battery was not finished though by the time the British flotilla arrived and was abandoned during the engagement.

The Americans built a signal station three miles below the installation and an earthen redoubt to defend the fort's rear side in case of a land assault. They also erected overhead cover above the fort's gun batteries to prevent shell fragments from hitting the gun-crews. The gunners repaired the worn-out U.S. artillery carriages and moved some to other batteries in the fort. They destroyed the old powder magazine, replacing it with several additional magazines that they built, which had wood and dirt piled on top to protect them. The idea being that if one powder magazine was destroyed, the others would still be usable.

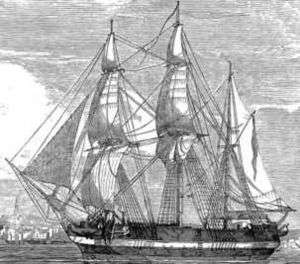

The British flotilla consisted of the sloop-of-war HMS Herald, the brig-of-war HMS Thistle, the schooner HMS Pigmy, and two bomb vessels, HMS Aetna and HMS Volcano.[2] The vessels provided armed longboats, armed barges, launches, and armed gigs.

A British landing party of unknown size soon captured and occupied the signal station and other areas around the land side of Fort St. Philip. This action effectively cut off the American land supply and communication lines.

Siege

With Major Walter H. Overton in command of the American forces, and Admiral Cochrane leading the British, the siege of Fort St. Philip began at 12:00 am on January 9, 1815 when the Royal Navy approached the fort, formed a line of battle and made preparations for a bombardment. Immediately the fort's furnace was lit for hot shot, burning red cannonballs that can have a devastating effect against warships.

At 1:00 pm, the signal station was abandoned and partially burned by the Americans who wanted to leave nothing for a fast-approaching British shore party. The men made it to their fort and the signal station fell into enemy hands. The preparations for a naval bombardment continued. At about 3:00 pm, the British sent a number of their boats forward to discover the strength of Fort St. Philip.

Two of the fort's batteries fired a salvo, hitting at least one of the longboats; this quickly forced the British to abandon their effort but not before the British learned of the American artillery strength on the riverside of the fort. St. Philip's riverside strength forced the larger UK vessels to stay out of range. Enabling the British only to fire their broadsides at great distances, around 3,960 yards from the American positions.

After learning of the American strength, the British commenced their bombardment at about 3:30 pm. The first shot fell too short and the second exploded over the fort. One shell fell every two minutes according to the U.S. commander and lasted all day and night of January 9. During the first day of battle, no Americans became casualties.

Due to the wet terrain from rain during most of the battle, a large quantity of the British cannonballs and shells slammed into the ground, buried themselves, and failed to explode. Some shots exploded underground but had no effect on the American troops above the surface. That same night, the British armed boats returned in strength, firing several rounds of grape and round shot into the fort.

The British force was reportedly so close to the fort that the Americans could hear the British officers shouting commands at their men. This close range allowed some of the American infantry to fire their small arms on the easy targets sitting in their boats. The Americans, believing this to be a British trick to distract their gunners and subsequently allow the British fleet to pass the fort, were ordered to not fire a shot from their heavy weapons.

The British failed to distract the Americans, so the boats withdrew for the night but continued to bombard the fort at long range. The next day, the siege continued with the British occasionally advancing their boats to fire on the Americans. One bombardment at 12:00 am for two hours and another advance and bombardment at sundown for two more hours.

On the third day, January 11, shrapnel struck the American flag post, nailing the halyards to the mast. The flag was removed for an hour which possibly made the British think the Americans were surrendering. The flag was repaired and replaced on the flag pole, an hour after lowering, by an American sailor who braved the British bombardment by climbing up the mast and securing the flag while shots burst overhead. The sailor completed this without injury.

At 12:00 am and sunset the British boats moved forward again and attacked. This pattern of British boat attacks continued for the remainder of the siege. Other than the first longboat attack, the American batteries fired on all of the other enemy longboat advances. Most of the shots fell too short.

The evening of January 11, the Royal Navy bombarded the fort's store house, thinking it to be the powder magazine. Several shots passed straight through the store house; two exploded within it, killing one man and wounding another. The real powder magazines escaped harm with the exception of the main magazine which suffered some minor damage but failed to explode.

Realizing that their weapons were not very effective during the first few days of battle, on January 14, the British re-fused all of their artillery projectiles to explode over the fort, in order to shower the garrison with shards of burning hot metal. The shots thus were more efficient and the Americans sustained another death and a few more wounded. The rounds also damaged several of the fort's gun carriages.

The British shells managed to silence the two American 32 pounders, but only for an hour before repairs were completed. On this night, still the 14th, several British rounds struck the blacksmith's shop, damaging it severely. By the night of January 15, the United States garrison constructed more adequate defenses around their batteries from stockpiles of wood which were being brought into the fort from the nearby forest.

The powder magazines were also reinforced by another layer of dirt. At some point one of the British bomb vessels came within range and was damaged by an American cannonball which put the ship out of action for a short while. On the morning of the 16th, almost constant rain had left the interior of the fort underwater, making it similar to a livestock pond. All of the garrison's tents were ripped up from shell fragments though they were unoccupied.

That same day, a U.S. supply boat arrived at the fort from New Orleans, carrying ammunition and fuses. This helped morale of the Americans, who were now in a better form for defense than when the battle began. The fighting continued during the night of the January 17 and just before daylight on the 18th; several shells were lodged in Fort St. Philip's parapet; one burst passing through a ditch and into the center bastion. These were the last shots the Americans received.

Throughout the rest of the day, the British remained in view of the fort but did not fire again. They withdrew their landing force and on January 19, 1815 the British abandoned their attempt to destroy the fort by sailing away to find an alternate waterway to New Orleans. After learning of the British defeat at the city, the Royal Navy canceled their cruise to reinforce their already defeated army.

Aftermath

The siege of Fort St. Philip ended with an American victory due to the British failure to pass the fort in order to reinforce the British army at New Orleans. The siege provided Andrew Jackson with valuable time to re-deploy his forces for another possible British invasion. Only two Americans were killed and seven were wounded while sustaining severe damage to their fort.

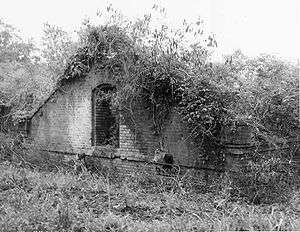

United Kingdom human casualties are unknown, one bomb vessel and several small boats were damaged though. Well over 1,000 British shots were fired, an estimated seventy tons of munitions. After the siege ended, the Americans discovered that over 100 enemy shells lay buried within the fort, unexploded. Nearly all of the buildings were in ruins and the ground for a half mile around the fort was littered with bomb craters.

Three currently active Regular Army battalions (1-5 FA, 1-1 Inf and 2-1 Inf) perpetuate the lineages of two American units (Wollstonecraft's Company, Corps of Artillery, and the old 7th Infantry) that were present at Fort St. Philip during the bombardment.

See also

- British occupation of St. Marys and Cumberland Island

- American South theatre of the War of 1812

- Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip

References

- Lossing, Benson (1868). The Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812. Harper & Brothers, Publishers. p. 1051.

- "Royal Marines on the Gulf Coast". Retrieved 3 June 2014.

Extracted information from the log of HMS Volcano

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- a b c d "Fort St. Philip". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. https://web.archive.org/web/20110308014818/http://tps.cr.nps.gov/nhl/detail.cfm?ResourceId=261&ResourceType=Structure. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- Patricia Heintzelman (1978), National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Fort St. PhilipPDF (506 KiB), National Park Service]|32 KB and Accompanying 6 photos, aerial photos from 1935 and others, undated. PDF (1.45 MiB)

- Sutton, James (2007-09-10). "Ft. St. Philip – Vella-Ashby". Panoramio. https://www.panoramio.com/photo/4502551. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- Marshall, John (1830). Royal naval biography; or, Memoirs of the services of all the flag-officers, superannuated rear-admirals, retired captains, post-captains, and commanders, whose names appeared on the Admiralty list of sea-officers at the commencement of the year 1823, or who have since been promoted. Supplement. Volume 4. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown and Green.

External links

- The Gulf Theatre in the War of 1812

- Siege of Fort St. Philip — eyewitness accounts, as published in the Louisiana Historical Quarterly