Batavia, Illinois

Batavia (/bəˈteɪviə/) is a city in DuPage and Kane Counties in the U.S. state of Illinois. A suburb of Chicago, it was founded in 1833 and is the oldest city in Kane County.[5] As of the 2010 census, the city had a total population of 26,045, which was estimated to have increased to 26,420 by July 2019.[6]

Batavia, Illinois | |

|---|---|

City | |

Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad Depot Museum | |

| Nicknames: The Windmill City, City of Energy[1] | |

| Motto(s): "Where Tradition and Vision Meet"[2] | |

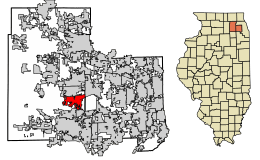

Location of Batavia in Kane County Illinois. | |

.svg.png) Location of Illinois in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 41°50′56″N 88°18′30″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Illinois |

| Counties | Kane, DuPage |

| Townships | Batavia (Kane), Geneva (Kane), Winfield (DuPage) |

| Settled | 1833 |

| Incorporated | July 27, 1872 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager |

| • Mayor | Jeff Schielke |

| Area | |

| • Total | 10.71 sq mi (27.75 km2) |

| • Land | 10.53 sq mi (27.27 km2) |

| • Water | 0.19 sq mi (0.48 km2) |

| Elevation | 666 ft (203 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 26,045 |

| • Estimate (2019)[4] | 26,420 |

| • Density | 2,509.26/sq mi (968.81/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Code(s) | 60510 and 60539 |

| Area codes | 630 and 331 |

| FIPS code | 17-04078 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2394077 |

| Wikimedia Commons | Batavia, Illinois |

| Website | www |

.jpg)

During the latter part of the 19th century, Batavia, home to six American-style windmill manufacturing companies, became known as "The Windmill City."[5] Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, a federal government-sponsored high-energy physics laboratory, where both the bottom quark and the top quark were first detected, is located in the city.

Batavia is part of a vernacular region known as the Tri-City area, along with St. Charles and Geneva, all western suburbs of similar size and relative socioeconomic condition.[7]

History

Batavia was first settled in 1833 by Christopher Payne and his family. Originally called Big Woods for the wild growth throughout the settlement, the town was renamed by local judge and former Congressman Isaac Wilson in 1840 after his former home of Batavia, New York.[8][9] Because Judge Wilson owned the majority of the town, he was given permission to rename the city.

Batavia's settlement was delayed one year by the Black Hawk War, in which Abraham Lincoln was a citizen soldier, and Zachary Taylor and Jefferson Davis were Army officers.[10] Although there is no direct evidence that Lincoln, Taylor, or Davis visited the future site of Batavia, there are writings by Lincoln that refer to "Head of the Big Woods," which was Batavia's original name from its first settler, Christopher Payne. The city was incorporated on July 27, 1872.[11]

After the death of her husband, Mary Todd Lincoln was an involuntary resident of the Batavia Institute on May 20, 1875.[12] At the time the institute was known as Bellevue Place, a sanitarium for women. Mrs. Lincoln was released four months later on September 11, 1875.[13] In the late 19th century, Batavia was a major manufacturer of the Conestoga wagons used in the country's westward expansion.[14] Into the early 20th century, most of the windmill operated waterpumps in use throughout America's farms were made at one of the three windmill manufacturing companies in Batavia.[15][16] Many of the original limestone buildings that were part of these factories are still in use today as government and commercial offices and storefronts. The Aurora Elgin and Chicago Railway constructed a power plant in southern Batavia and added a branch to the city in 1902. The Campana Factory was built in 1936 to manufacture cosmetics for The Campana Company, most notably Italian Balm, the nation's best-selling hand lotion at the time.

Geography

Batavia is located at 41°50′56″N 88°18′30″W (41.8488583, −88.3084400).[17]

According to the 2010 census, Batavia has a total area of 9.707 square miles (25.14 km2), of which 9.64 square miles (24.97 km2) (or 99.31%) is land and 0.067 square miles (0.17 km2) (or 0.69%) is water.[18]

- Major streets

- Batavia Avenue (IL-31)

- Main Street (Route 10)

- Randall Road

- Washington Street/River Street (IL-25)

- Wilson Street

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 1,621 | — | |

| 1880 | 2,639 | — | |

| 1890 | 3,543 | 34.3% | |

| 1900 | 3,871 | 9.3% | |

| 1910 | 4,436 | 14.6% | |

| 1920 | 4,395 | −0.9% | |

| 1930 | 5,045 | 14.8% | |

| 1940 | 5,101 | 1.1% | |

| 1950 | 5,838 | 14.4% | |

| 1960 | 7,496 | 28.4% | |

| 1970 | 9,060 | 20.9% | |

| 1980 | 12,574 | 38.8% | |

| 1990 | 17,076 | 35.8% | |

| 2000 | 23,866 | 39.8% | |

| 2010 | 26,045 | 9.1% | |

| Est. 2019 | 26,420 | [4] | 1.4% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[19] | |||

As of the 2000 U.S. census, there were 23,866 people, 8,494 households, and 6,268 families residing in the city.[20] The population density was 2,638.4 people per square mile (1,018.2/km2). There were 8,806 housing units at an average density of 973.5 per square mile (375.7/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 93.21% White, 2.42% Black or African American, 0.11% Native American, 1.35% Asian, none Pacific Islander, 1.53% from other races, and 1.39% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 5.27% of the population.

There were 8,494 households, out of which 41.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 63.0% were married couples living together, 7.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 26.2% were non-families. 22.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.75 and the average family size was 3.27.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 31.3% under the age of 18, 6.0% from 18 to 24, 30.6% from 25 to 44, 22.2% from 45 to 64, and 9.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 94.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 89.4 males.

Males had a median income of $55,913 versus $35,083 for females. The per capita income for the city was $38,576. About 2.5% of families and 3.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 4.1% of those under age 18 and 5.6% of those age 65 or over.

According to the 2008 U.S. Census Bureau estimate, the median income for a household in the city was $90,680, the median income for a family was $103,445, and the median home value was $329,800.[21]

Economy

Aldi, Inc., the U.S. subsidiary of Aldi Süd, has its headquarters in Batavia.[22]

Fermilab is located just outside the town borders and serves as employment for many of the town's residents.

According to the City's 2017 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[23] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fermi Research Alliance | 1,700 |

| 2 | Suncast Corporation | 800 |

| 3 | Aldi, Inc. | 500 |

| 4 | AGCO Corporation | 365 |

| 5 | Power Packaging | 300 |

| 6 | HOBI International | 225 |

| 7 | VWR Scientific | 221 |

| 8 | Batavia Container | 160 |

| 9 | Flinn Scientific Inc. | 150 |

| 10 | DS Containers, Inc. | 140 |

Accolades

Batavia is an award-winning community.

- In 2007, BusinessWeek ranked Batavia #21 on a national list of the 50 best places in America to raise kids.[24]

- In 2009, Batavia was ranked #56 on CNN Money's Best Small Towns in the nation.

- In 2011, Batavia was voted by RelocateAmerica as one of the Top 100 Places to Live in America.[25]

- In 2013, Batavia won the Best Street Award from the Illinois Chapter of the Congress of New Urbanism for the City's Streetscape redevelopment of River Street.[26] The River Street design was also awarded the Lieutenant Governor's Award for Excellence in Downtown Revitalization at the Illinois Main Street Conference in 2013.[27]

- In 2013, the City of Batavia was designated as a Bike Friendly Community (Bronze Level) by the League of American Bicyclists. Currently, only six communities in Illinois are designated Bike Friendly Communities.[28][29]

- In 2013, Batavia's collection of historic windmills was designated as an Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

- In 2020, the City of Batavia's Wastewater Treatment Plant rehabilitation project won a Project of the Year Award from the American Public Works Association Fox Valley Branch in the environmental category in the $25-$75 million division.[30]

Education

Batavia is served by Batavia Public School District No. 101. The district currently consists of six K–5 elementary schools, one 6–8 middle school, and Batavia High School.[31] Small pockets of the city are served by Geneva Community Unit School District 304 and West Aurora Public School District 129.

Library

Batavia is served by Batavia Public Library District, which was founded in April 1881 as a township library; the first Board of Library Trustees was elected in April 1882. It converted to a district library in June 1975. The library serves most of Batavia Township, Kane County, Illinois and portions of Winfield Township, DuPage County, Illinois, Geneva Township, Kane County, Illinois, and Blackberry Township, Kane County, Illinois. Its current facility opened in January 2002.[32]

Transportation

Notable people

- Ken Anderson, quarterback with the Cincinnati Bengals; grew up in Batavia[33]

- Charlie Briggs, second baseman with the Chicago Browns

- Bernard J. Cigrand, father of Flag Day; lived in Batavia

- Jackie DeShannon, 1960s singer-songwriter; attended Batavia High School

- J.W. Eddy, 19th Century politician, lawyer and railway engineer, acquaintance of Abe Lincoln; lived in Batavia

- Winfield S. Hall, physiologist and writer[34]

- Dan Issel, power forward and coach in the Basketball Hall of Fame[35]

- Mary Todd Lincoln, President Abraham Lincoln's wife; committed by her son to the Bellevue Place psychiatric hospital in Batavia (1875)[12]

- Samuel D. Lockwood, politician and judge

- Meredith Mallory, former US Congressman

- John F. Petit, businessman and politician; lived in Batavia[36]

- Birgit Ridderstedt, folk singer and producer

- Craig Sager, sportscaster for TNT and TBS; born in Batavia[37]

- Isaac Wilson, former US Congressman

See also

References

- Edwards, Jim; Edwards, Wynette (2000). "City of Energy Entrepreneurs". Batavia: From the Collection of the Batavia Historical Society. Chicago, IL: Arcadia. pp. 21–32. ISBN 978-0-7385-0795-8.

- "City of Batavia, Illinois". City of Batavia, Illinois. Retrieved August 31, 2012.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Schielke, Jeffery (2010). "Batavia History: Our Town". City of Batavia. Archived from the original on 2010-10-17. Retrieved 2010-02-08.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- [Scheetz, George H.] "Whence Siouxland?" Book Remarks [Sioux City Public Library], May 1991.

- Callery, Edward (2009). Place names of Illinois. Champaign-Urbana, Ill: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-03356-8.

- "Several Towns Named After Founders and Heroes". The Daily Herald. December 28, 1999. p. 220. Retrieved August 17, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- Blackhawk War

- Illinois Regional Archives Depository System. "Name Index to Illinois Local Governments". Illinois State Archives. Illinois Secretary of State. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- Emerson, Jason (June–July 2006). "The Madness of Mary Lincoln". American Heritage. Archived from the original on 2009-09-05. Retrieved 2009-09-03.

- "Mary Lincoln's Stay at Bellevue Place". www.abrahamlincolnonline.org.

- Robinson, Marilyn; Schielke, Jeffery D.; Gustafson, John (1998) [1962]. John Gustafson's Historic Batavia. Batavia, Ill: Batavia Historical Society. ISBN 0-923889-06-X. OCLC 38030962.

- Cisneros, Stacey L.; Scheetz, George H. (2008). Windmill City: A Guide to the Historic Windmills of Batavia, Illinois. Batavia, Ill: Batavia Public Library. OCLC 247081989.

- "Batavia History". Batavia Historical Society. 2000. Archived from the original on 2010-01-15. Retrieved 2010-02-08.

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: City of Batavia

- "G001 - Geographic Identifiers - 2010 Census Summary File 1". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2020-02-13. Retrieved 2015-12-25.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Batavia city, Illinois - Fact Sheet". American FactFinder. United States Census Bureau. 2000. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2010-02-08.

- "2006-2008 American Community Survey 3-Year Estimates". American FactFinder. United States Census Bureau. 2008. Archived from the original on 2020-02-10. Retrieved 2010-02-08.

- Wollam, Allison. "Discount retailers bulk up in Houston as economy stutters." Houston Business Journal. Monday November 28, 2011. Retrieved on December 8, 2011.

- "Financial Reports". Batavia, IL - Official Website. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-09-30. Retrieved 2011-06-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-08-14. Retrieved 2012-08-03.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "CNU Illinois". cnuillinois.

- "Archived copy". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 2014-05-08. Retrieved 2014-05-07.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-05-08. Retrieved 2014-05-07.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Batavia Wins National Recognition as Bicycle Friendly Community". Batavia, IL Patch. October 15, 2013.

- "Batavia, IL". Batavia, IL.

- "Batavia Public Schools". Batavia Public School District No. 101. 2010. Archived from the original on 18 January 2010. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- "Library History". Batavia Public Library. 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-10-30. Retrieved 2010-02-08.

- "Ken Anderson". IMDb. Retrieved October 19, 2012.

- White, James Terry. (1944). The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography. Volume 31. New York: James T. White & Company. p. 446

- "Dan Issel". NBA Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on November 9, 2012. Retrieved October 22, 2012.

- 'Illinois Blue Book 1937-1938,' Biographical Sketch of John F. Petit, pg. 160-161

- "Craig Sager". CNN/Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on August 23, 2011. Retrieved October 22, 2012.