Huaxia

Huaxia is a historical concept representing the Chinese nation and civilization, and came from the self-awareness of a common cultural ancestry by the various confederacy (pre-Qin) era Han Chinese people.

| Huaxia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

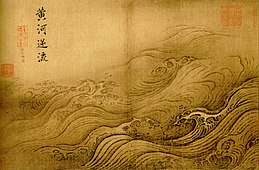

The Yellow River Breaches its Course by Ma Yuan, Song dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 華夏 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 华夏 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | beautiful grandeur | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Names of China |

|---|

Etymology

According to the Zuo zhuan, xia (夏) signified the "grandness" in the ceremonial etiquette of China, while hua (華) was used in reference to the "beauty" in the clothing that the Chinese people wore (中國有禮儀之大,故稱夏;有服章之美,謂之華).[1][2]

History

Origin

Huaxia refers to a confederation of tribes—living along the Yellow River—who were the ancestors of what later became the Han ethnic group in China.[3][4] During the Warring States (475–221 BCE), the self-awareness of the Huaxia identity developed and took hold in ancient China.[4] Initially, Huaxia defined mainly a civilized society that was distinct and stood in contrast to what was perceived as the barbaric peoples around them.[5]

Modern usage

Although still used in conjunction, the Chinese characters for hua and xia are also used separately as autonyms.

The official Chinese names of both the People's Republic of China (PRC) and the Republic of China (ROC) use the term Huaxia in combination with the term Zhongguo (中國, 中国, translated as "Middle Kingdom"), that is, as Zhonghua (中華, 中华).[6] The PRC's official Chinese name is Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo (中华人民共和国), while that of the ROC is Zhonghua Minguo (中華民國). The term Zhongguo is confined by its association to a state, whereas Zhonghua mainly concerns culture.[7] The latter is being used as part of the nationalist term Zhōnghuá Mínzú which is an all Chinese nationality in the sense of a multi-ethnic national identity.

The term Huaren (華人) for a Chinese person is an abbreviation of Huaxia with ren (人, person).[8] Huaren in general is used for people of Chinese ethnicity, in contrast to Zhongguoren (中國人) which usually (but not always) refers to citizens of China.[7] Although some may use Zhongguoren to refer to the Chinese ethnicity, such usage is not accepted by some in Taiwan.[7] In overseas Chinese communities in countries such as Singapore and Malaysia, Huaren or Huaqiao (overseas Chinese) is used as they are not citizens of China.[9][10]

See also

- Yan Huang Zisun, literally the "Descendants of Yan and Huang"

- Zhongyuan, the central regions associated with Huaxia

- Zhonghua (disambiguation)

References

- Liu, Xuediao [劉學銚] (2005). 中國文化史講稿 (in Chinese). Taipei: 知書房出版集團. p. 9. ISBN 978-986-7640-65-9.

古時炎黃之胄常自稱,「華夏」有時又作「諸夏」《左傳》定公十年(西元前 500 年)有:裔不謀夏,夷不亂華。對於此句其疏曰:中國有禮儀之大,故稱夏;有服章之美,謂之華。

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Zhu, Ruixi; Zhang, Bangwei; Liu, Fusheng; Cai, Chongbang; Wang, Zengyu (2016). A Social History of Medieval China. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107167865.

To quote an ancient text, "there is grand ceremonial etiquette so it is called xia (夏), and there is the beauty of apparel which is called hua (华)."[1] (And that's how China is also called huaxia [华夏].) [...] [1] 'The Tenth Year of Duke Ding of Lu' (定公十年), Zuo Qiuming's Commentary on Spring and Autumn Annals (左傳), explained by Yan Shigu (顏師古, 581–645).

- Cioffi-Revilla, Claudio; Lai, David (1995). "War and Politics in Ancient China, 2700 BC to 722 BC". The Journal of Conflict Resolution. 39 (3): 471–72. doi:10.1177/0022002795039003004.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Guo, Shirong; Feng, Lisheng (1997). "Chinese Minorities". In Selin, Helaine (ed.). Encyclopaedia of the history of science, technology and medicine in non-western cultures. Dordrecht: Kluwer. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-79234066-9.

During the Warring Stares (475 BC–221 BC), feudalism was developed and the Huaxia nationality grew out of the Xia, Shang, and Zhou nationalities in the middle and upper reaches of the Yellow River. The Han evolved from the Huaxia.

- Holcombe, Charles (2010). A history of East Asia: From the origins of civilization to the twenty-first century. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-521-73164-5.

Initially, Huaxia seems to have been a somewhat elastic cultural marker, referring neither to race nor ethnicity nor any particular country but rather to "civilized," settled, literate, agricultural populations adhering to common ritual standards, in contrast to "barbarians."

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Holcombe, Charles (2011). A history of East Asia: From the origins of civilization to the twenty-first century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-521-73164-5.

Zhongguo — [...] Today, Zhongguo is probably the closest Chinese-language equivalent to the English word China. Even so, both the modern People's Republic of China, on the mainland, and the Republic of China (confined to the island of Taiwan since 1949) are still officially known, instead, by a hybrid combination of the two ancient terms Zhongguo and Huaxia: Zhonghua 中華.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Hui-Ching Chang, Richard Holt (2014-11-20). Language, Politics and Identity in Taiwan: Naming China. Routledge. pp. 162–164. ISBN 9781135046354.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Solé-Farràs, Jesús (2013). New Confucianism in twenty-first century China: The construction of a discourse. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-13473908-0.

Huaren 華人 equivalent to a 'Chinese person'—hua 華 is the abbreviation of Huaxia, a synonym of Zhongguo 中國 (China), and ren 人 is 'person'.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Sheng Lijun (30 June 2002). China and Taiwan: Cross-strait Relations Under Chen Shui-bian. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 53. ISBN 978-9812301109.

- Karl Hack, Kevin Blackburn (30 May 2012). War Memory and the Making of Modern Malaysia and Singapore. NUS Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-9971695996.