Geshtinanna

Geshtinanna (also known as Geštinanna or Ngeshtin-ana) is the ancient Sumerian goddess of agriculture, fertility, and dream interpretation, the so-called "heavenly grape-vine". She is the sister of Dumuzid and consort of Ningisida. She is also the daughter of Enki and Ninhursag. She shelters her brother when he is being pursued by galla demons and mourns his death after the demons drag him to Kur. She eventually agrees to take his place in Kur for half the year, allowing him to return to Heaven to be with Inanna. The Sumerians believed that, while Geshtinanna was in Heaven and Dumuzid in Kur, the earth became dry and barren, thus causing the season of summer.

Worship

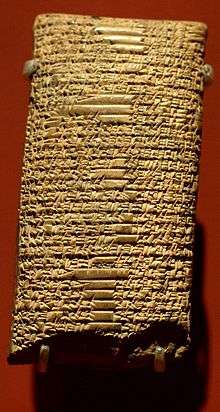

Geshtinanna is first attested in texts from the Early Dynastic IIIb Era. Her main cult centers were the cities of Nippur, Isin, and Uruk. She continued to be worshipped throughout the Akkadian Period, but her cult seems to have disappeared during the Old Babylonian Era. Even after she ceased to be worshipped, however, her name was not forgotten; she is mentioned in various antiquitarian works as late as the Seleucid Era.[1] Geshtinanna was viewed as a mother goddess[2] and was closely associated with the interpretation of dreams.[2] Like her brother Dumuzid, she was also a rural deity, associated with the countryside and open fields.[2]

Mythology

The Dream of Dumuzid

The Sumerian poem The Dream of Dumuzid begins with Dumuzid telling Geshtinanna about a frightening dream he has experienced. Then the galla demons arrive to drag Dumuzid down into the Underworld as a replacement for his wife Inanna, who has been rescued from the Underworld by Enki, the Sumerian god of water. Dumuzid flees and hides. The galla demons brutally torture Geshtinanna in an attempt to force her to tell them where Dumuzid is hiding. Geshtinanna, however, refuses to tell them where her brother has gone. The galla go to Dumuzid's unnamed "friend," who betrays Dumuzid, telling the galla exactly where Dumuzid is hiding. The galla capture Dumuzid, but Utu, the god of the Sun, who also happens to be Inanna's brother, rescues Dumuzid by transforming him into a gazelle. Eventually, the galla recapture Dumuzid and drag him down into the Underworld.[3][4]

The Return of Dumuzid

In the Sumerian poem The Return of Dumuzid, which picks up where The Dream of Dumuzid ends, Geshtinanna laments continually for days and nights over Dumuzid's death, joined by Inanna, who has apparently experienced a change of heart, and Sirtur, Dumuzid's mother. The three ladies mourn continually until a fly reveals to Inanna the location of her husband. Together, Inanna and Geshtinanna go to the place where the fly has told them they will find Dumuzid. They find him there and Inanna determines that, from that point onwards, Dumuzid will spend half of the year with her in Heaven and the other half of the year with her sister Ereshkigal in the Underworld.[5]

References

- Richter 2004.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 88.

- Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 74-84.

- http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr143.htm

- Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 85-89.

Bibliography

- Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony (1992), Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary, The British Museum Press, ISBN 0-7141-1705-6CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Michael Jordan (2002). Encyclopedia of Gods. Kyle Cathie Limited.

- Richter, T. (2004), Untersuchenungen zu den lokalen Panthea Süd- und Mittelbabyloniens in altbabylonidcher Zeit, 2, Münster, Germany: Ugarit-Verlag

- Wolkstein, Diane; Kramer, Samuel Noah (1983), Inanna: Queen of Heaven and Earth: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer, New York: Harper & Row Publishers

_-_EnKi_(Sumerian).jpg)