Aquileia

Aquileia (UK: /ˌækwɪˈliːə/ AK-wil-EE-ə,[3] US: /ˌɑːkwɪˈleɪə/ AH-kwil-AY-ə,[4] Italian: [akwiˈlɛːja]; Friulian: Olee / Olea / Acuilee / Aquilee / Aquilea;[5] Venetian: Aquiłeja / Aquiłegia; German: Aglar / Agley / Aquileja; Slovene: Oglej) is an ancient Roman city in Italy, at the head of the Adriatic at the edge of the lagoons, about 10 kilometres (6 mi) from the sea, on the river Natiso (modern Natisone), the course of which has changed somewhat since Roman times. Today, the city is small (about 3,500 inhabitants), but it was large and prominent in Antiquity as one of the world's largest cities with a population of 100,000 in the 2nd century AD.[6][7] and is one of the main archeological sites of Northern Italy.

Aquileia | |

|---|---|

| Comune di Aquileia | |

The Basilica of Aquileia. | |

Coat of arms | |

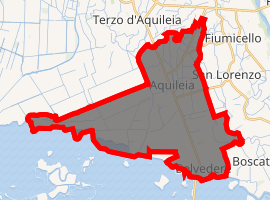

Location of Aquileia

| |

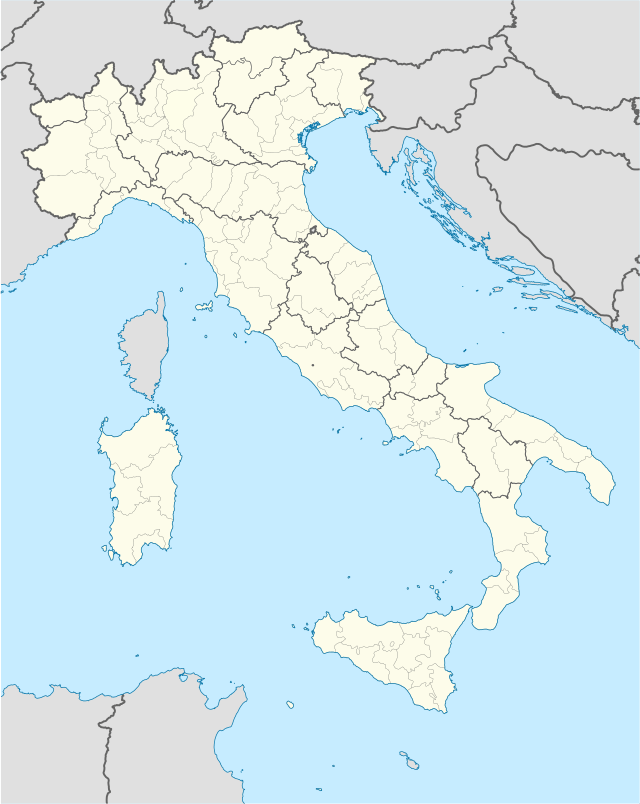

Aquileia Location of Aquileia in Italy  Aquileia Aquileia (Friuli-Venezia Giulia) | |

| Coordinates: 45°46′11.01″N 13°22′16.29″E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Friuli-Venezia Giulia |

| Province | Udine (UD) |

| Frazioni | Beligna, Belvedere, Viola, Monastero |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Emanuele Zorino |

| Area | |

| • Total | 37.44 km2 (14.46 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 5 m (16 ft) |

| Population (30 April 2017)[2] | |

| • Total | 3,302 |

| • Density | 88/km2 (230/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Aquileiesi |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 33051 |

| Dialing code | 0431 |

| Patron saint | Sts. Hermagoras and Fortunatus |

| Saint day | July 12 |

| Website | Official website |

| Official name | Archaeological Area and the Patriarchal Basilica of Aquileia |

| Criteria | Cultural: iii, iv, vi |

| Reference | 825 |

| Inscription | 1998 (22nd session) |

History

Roman Era

Aquileia was founded as a colony by the Romans in 180/181 BC along the Natiso River, on land south of the Julian Alps but about 13 kilometres (8 mi) north of the lagoons. The colony served as a strategic frontier fortress at the north-east corner of transpadane (on the far side of the Po river) Italy and was intended to protect the Veneti, faithful allies of Rome during the invasion of Hannibal and the Illyrian Wars. The colony would serve as a citadel to check the advance into Cisalpine Gaul of other warlike peoples, such as the hostile Carni to the northeast in what is now Carnia and Histri tribes to the southeast in what is now Istria. In fact, the site chosen for Aquileia was about 6 km from where an estimated 12,000 Celtic Taurisci nomads had attempted to settle in 183 BC. However, since the 13th century BC, the site, on the river and at the head of the Adriatic, had also been of commercial importance as the end of the Baltic amber (sucinum) trade. It is, therefore, theoretically not unlikely that Aquileia had been a Gallic oppidum even before the coming of the Romans. However, few Celtic artifacts have been discovered from 500 BC to the Roman arrival.[8]

The colony was established with Latin rights by the triumvirate of Publius Cornelius Scipio Nasica, Caius Flaminius, and Lucius Manlius Acidinus, two of whom were of consular and one of praetorian rank. Each of the men had first hand knowledge of Cisalpine Gaul. Nasica had conquered the Boii in 191. Flaminius had overseen the construction of the road named after him from Bologna to Arezzo. Acidinus had conquered the Taurisci in 183.[9][10]

The triumvirate led 3,000 families to settle the area meaning Aquileia probably had a population of 20,000 soon after its founding. Meanwhile, based on the evidence of names chiseled on stone, the majority of colonizing families came from Picenum, Samnium, and Campania, which also explains why the colony was Latin and not Roman. Among these colonists, pedites received 50 iugera of land each, centuriones received 100 iugera each, and equites received 140 iugera each. Either at the founding or not long afterward, colonists from the nearby Veneti supplemented these families.[8]

Roads soon connected Aquileia with the Roman colony of Bologna probably in 173 BC. In 148 BC, it was connected with Genua by the Via Postumia, which stretched across the Padanian plain from Aquileia through or near to Opitergium, Tarvisium, Vicetia, Verona, Bedriacum, and the three Roman colonies of Cremona, Placentia, and Dertona. The construction of the Via Popilia from the Roman colony of Ariminium to Ad Portum near Altinum in 132 BC improved communications still further. In the 1st century AD, the Via Gemina would link Aquileia with Emona to the east of the Julian Alps, and by 78 or 79 AD the Via Flavia would link Aquileia to Pula.

Meanwhile, in 169 BC, 1,500 more Latin colonists with their families, led by the triumvirate of Titus Annius Lucius, Publius Decius Subulo, and Marcus Cornelius Cethegus, settled in the town as a reinforcement to the garrison.[11] The discovery of the gold fields near the modern Klagenfurt in 130 BC[12] brought the growing colony into further notice, and it soon became a place of importance, not only owing to its strategic military position, but as a center of commerce, especially in agricultural products and viticulture. It also had, in later times at least, considerable brickfields.

In 90 BC, the original Latin colony became a municipium and its citizens were ascribed to the Roman tribe Velina. The customs boundary of Italy was close by in Cicero's day. Caesar visited the city on a number of occasions and pitched winter camp nearby in 59-58 BC.

Although the Iapydes plundered Aquileia during the Augustan period, subsequent increased settlement and no lack of profitable work meant the city was able to develop its resources. Jewish artisans established a flourishing trade in glasswork. Metal from Noricum was forged and exported. The ancient Venetic trade in amber from the Baltic continued. Wine, especially its famous Pucinum was exported. Oil was imported from Proconsular Africa. By sea, the port of Aquae Gradatae, modern Grado, Friuli-Venezia Giulia was developed. On land, Aquileia was the starting-point of several important roads leading outside Italy to the north-eastern portion of the empire — the road (Via Iulia Augusta) by Iulium Carnicum to Veldidena (mod. Wilten, near Innsbruck), from which branched off the road into Noricum, leading by Virunum (Klagenfurt) to Laurieum (Lorch) on the Danube, the road leading via Emona into Pannonia and to Sirmium (Sremska Mitrovica), the road to Tarsatica (near Fiume, now Rijeka) and Siscia (Sisak), and the road to Tergeste (Trieste) and the Istrian coast.

Augustus was the first of a number of emperors to visit Aquileia, notably during the Pannonian wars in 12‑10 BC. It was the birthplace of Tiberius' son by Julia, in the latter year. The Roman poet Martial praised Aquileia as his hoped for haven and resting place in his old age.[13]

In terms of religion, the populace adopted the Roman pantheon, although the Celtic sungod, Belenus, had a large following. Jews practiced their ancestral religion and it was perhaps some of these Jews who became the first Christians. Meanwhile, soldiers brought the martial cult of Mithras.

In the war against the Marcomanni in 167, the town was hard pressed; its fortifications had fallen into disrepair during the long peace. Nevertheless, when in 168 Marcus Aurelius made Aquileia the principal fortress of the empire against the barbarians of the North and East, it rose to the pinnacle of its greatness and soon had a population of 100,000. Septimius Severus visited in 193. In 238, when the town took the side of the Senate against the Emperor Maximinus Thrax, the fortifications were hastily restored, and proved of sufficient strength to resist for several months, until Maximinus himself was assassinated.

An imperial palace was constructed in Aquileia, in which the emperors after the time of Diocletian frequently resided.

During the 4th century, Aquileia maintained its importance. Constantine sojourned there on numerous occasions. It became a naval station and the seat of the Corrector Venetiarum et Histriae; a mint was established, of which the coins were very numerous, and the Catholic bishop obtained the rank of metropolitan archbishop. A council held in the city in 381 was only the first of a series of Councils of Aquileia that have been convened over the centuries. However, the city played a part in the struggles between the rulers of the 4th century. In 340, Emperor Constantine II was killed nearby while invading the territory of his younger brother Constans.

Late Roman Empire and Middle Ages

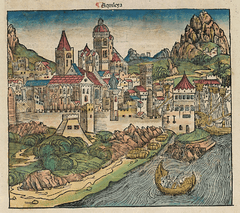

At the end of the 4th century, Ausonius enumerated Aquileia as the ninth among the great cities of the world, placing Rome, Constantinople, Carthage, Antioch, Alexandria, Trier, Mediolanum, and Capua before it. However, such prominence made it a target and Alaric and the Visigoths besieged it in 401, during which time some of its residents fled to the nearby lagoons. Alaric again attacked it in 408. Attila attacked the city in 452. During this invasion, on July 18, Attila and his Huns so utterly destroyed the city that it was afterwards hard to recognize its original site. The fall of Aquileia was the first of Attila's incursions into Roman territory; followed by cities like Mediolanum and Ticinum.[14] The Roman inhabitants, together with those of smaller towns in the neighborhood, fled en masse to the lagoons, and so laid the foundations of the cities of Venice and nearby Grado.

Yet Aquileia would rise again, though much diminished, and continue to exist until the Lombards invaded in 568; the Lombards destroyed it a second time in 590. Meanwhile, the patriarch fled to the island town of Grado, which was under the protection of the Byzantines. When the patriarch residing in Grado reconciled with Rome in 606, those continuing in the Schism of the Three Chapters, rejecting the Second Council of Constantinople, elected a patriarch at Aquileia. Thus, the diocese was essentially divided into two parts, with the mainland patriarchate of Aquileia under the protection of the Lombards, and the insular patriarchate of Aquileia seated in Grado being protected by the exarchate of Ravenna and later the Doges of Venice, with the collusion of the Lombards. The line of the patriarchs elected in Aquileia would continue in schism until 699CE. However, although they kept the title of patriarch of Aquileia, they moved their residence first to Cormons and later to Cividale.

The Lombard Dukes of Friuli ruled Aquileia and the surrounding mainland territory from Cividale. In 774, Charlemagne conquered the Lombard duchy and made it into a Frankish one with Eric of Friuli as duke. In 787, Charlemagne named the priest and master of grammar at the Palace School Paulinus the new patriarch of Aquileia. The patriarchate, despite being divided with a northern portion assigned to the pastoral care of the newly created Archbishopric of Salzburg, would remain one of the largest dioceses. Although Paulinus resided mainly at Cividale, his successor Maxentius considered rebuilding Aquileia. However, the project never came to fruition.

While Maxentius was patriarch, the pope approved the Synod of Mantua, which affirmed the precedence of the mainland patriarch of Aquileia over the patriarch of Grado. However, material conditions were soon to worsen for Aquileia. The ruins of Aquileia were continually pillaged for building material. And with the collapse of the Carolingians in the 10th century, the inhabitants would suffer under the raids of the Magyars.

By the 11th century, the patriarch of Aquileia had grown strong enough to assert temporal sovereignty over Friuli and Aquileia. The Holy Roman Emperor gave the region to the patriarch as a feudal possession. However, the patriarch's temporal authority was constantly disputed and assailed by the territorial nobility.

In 1027 and 1044 Patriarch Poppo of Aquileia, who rebuilt the cathedral of Aquileia, entered and sacked neighboring Grado, and, though the Pope reconfirmed the Patriarch of the latter in his dignities, the town never fully recovered, though it continued to be the seat of the Patriarchate until its formal transference to Venice in 1450.

In the 14th century the Patriarchal State reached its largest extension, stretching from the Piave river to the Julian Alps and northern Istria. The seat of the Patriarchate of Aquileia had been transferred to Udine in 1238, but returned to Aquiliea in 1420 when Venice annexed the territory of Udine.

In 1445, the defeated patriarch Ludovico Trevisan acquiesced in the loss of his ancient temporal estate in return for an annual salary of 5,000 ducats allowed him from the Venetian treasury. Henceforth only Venetians were allowed to hold the title of Patriarch of Aquileia. The Patriarchal State was incorporated in the Republic of Venice with the name of Patria del Friuli, ruled by a provveditore generale or a luogotenente living in Udine. The Patriarchal diocese was only finally officially suppressed in 1751, and the sees of Udine and Gorizia established from its territory.

Notable people

Saint Chrysogonus was martyred here in the beginning of the 4th century.

Main sights

Cathedral

The Aquileia Cathedral is a flat-roofed basilica erected by Patriarch Poppo in 1031 on the site of an earlier church, and rebuilt about 1379 in the Gothic style by Patriarch Marquard of Randeck.

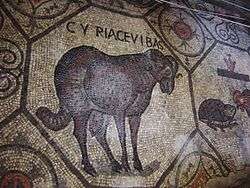

The façade, in Romanesque-Gothic style, is connected by a portico to the so-called Church of the Pagans, and the remains of the 5th-century baptistry. The interior has a nave and two aisles, with a noteworthy mosaic pavement from the 4th century. The wooden ceiling is from 1526, while the fresco decoration belongs to various ages: from the 4th century in the St. Peter's chapel of the apse area; from the 11th century in the apse itself; from the 12th century in the so-called "Crypt of the Frescoes", under the presbytery, with a cycle depicting the origins of Christianity in Aquileia and the history of St. Hermagoras, first bishop of the city.

Next to the 11th-century Romanesque chapel of the Holy Sepulchre, at the beginning of the left aisle, flooring of different ages can be seen: the lowest is from a Roman villa of the age of Augustus; the middle one has a typical cocciopesto pavement; the upper one, bearing blackening from Attila's fire, has geometrical decorations.

Externally, behind the 9th-century campanile and the apse, is the Cemetery of the Fallen, where ten unnamed soldiers of World War I are buried. Saint Hermagoras is also buried there.

Ancient Roman Remains

Today, Aquileia is a town smaller than the colony first founded by Rome. Over the centuries, sieges, earthquakes, floods, and pillaging of the ancient buildings for materials means that no edifices of the Roman period remain above ground. The site of Aquileia, believed to be the largest Roman city yet to be excavated, is inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. Excavations, however, have revealed some of the layout of the Roman town such as a segment of a street, the north-west angle of the town walls, the river port, and the former locations of baths, of an amphitheater, of a Circus, of a cemetery, of the Via Sacra, of the forum, and of a market. The National Archaeological Museum contains over 2,000 inscriptions, statues and other antiquities, mosaics, as well as glasses of local production and a numismatics collection.

Others

In the Monastero fraction is a 5th-century Christian basilica, later a Benedictine monastery, which today houses the Paleo-Christian Museum.

Twin towns – sister cities

Aquileia is twinned with the following settlements:[15]

See also

- Schism of the Three Chapters

- Aquileian rite

- Councils of Aquileia

- List of Aquileia Bishops and patriarchs

- Acaste Bresciani

References

- "Superficie di Comuni Province e Regioni italiane al 9 ottobre 2011". Istat. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- "Popolazione Residente al 1° Gennaio 2018". Istat. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- "Aquileia". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved April 6, 2019.

- "Aquileia". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved April 6, 2019.

- Bilingual name of Aquileja – Oglej in: Gemeindelexikon, der im Reichsrate Vertretenen Königreiche und Länder. Herausgegeben von der K.K. Statistischen Zentralkommission. VII. Österreichisch-Illyrisches Küstenland (Triest, Görz und Gradiska, Istrien) (in German). Vienna. 1910.

- The Oxford Classical Dictionary, p. 129, at Google Books

- A Brief History of Venice, p. 16, at Google Books

- G. Bandelli, "Aquileia dalla fondazione al II secolo d.C" in Aquileia dalla fondazione al alto medioevo, M. Buora, ed. (Udine: Arte Grafiche Friulane, 1982), 20.

- Livy, XL, 34, 2-4.

- E. Mangani, F. Rebecchi, and M.J. Srazzulla, Emilia Venezie (Bari: Laterza & Figli, 1981), 210.

- Livy XLIII 17,1

- Strabo IV. 208

- Martial, Epigrams lib. 4, 25: Aemula Baianis Altini litora villis et Phaethontei conscia silva rogi, quaeque Antenoreo Dryadum pulcherrima Fauno nupsit ad Euganeos Sola puella lacus, et tu Ledaeo felix Aquileia Timauo, hic ubi septenas Cyllarus hausit aquas: uos eritis nostrae requies portusque senectae, si iuris fuerint otia nostra sui. http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/martial/mart4.shtml

- Jordanus (1997). "THE ORIGINS AND DEEDS OF THE GOTHS". Getica. University of Calgary. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- "Gemellaggi". Retrieved 4 November 2014.

Sources

- Catholic Encyclopedia

- Neher in Kirchenlexikon I, 1184–89

- De Rubeis, Monumenta Eccles. Aquil. (Strasburg, 1740)

- Ferdinando Ughelli, Italia Sacra, I sqq.; X, 207

- Cappelletti, Chiese d'Italia, VIII, 1 sqq.

- Menzano, Annali del Friuli (1858–68)

- Paschini, Sulle Origini della Chiesa di Aquileia (1904)

- Glaschroeder, in Buchberger's Kirchl. Handl. (Munich, 1904), I, 300-301

- Hefele, Conciliengesch. II, 914–23.

- For the episcopal succession, see P. B. Gams, Series episcoporum (Ratisbon, 1873–86), and Eubel, Hierarchia Catholica Medii Aevi (Muenster, 1898).

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Aquileia. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aquileia. |

- Aquileia virtual tour (Italian Landmarks)

- Pre-Roman and Celtic Aquileia

- Aquileia featured on 10 Euro Italian Coin