Amtrak Cascades

The Amtrak Cascades is a passenger train corridor in the Pacific Northwest, operated by Amtrak in partnership with the U.S. states of Washington and Oregon. It is named after the Cascade mountain range that the route parallels. The 467-mile (752 km) corridor runs from Vancouver, British Columbia, through Seattle, Washington and Portland, Oregon to Eugene, Oregon.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

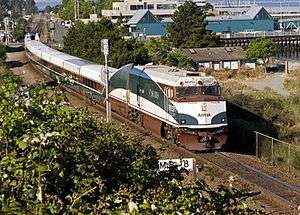

The Cascades near Edmonds, Washington in 2006 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service type | Inter-city rail | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Operating (truncated) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | Pacific Northwest | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | BN/UP/SP corridor trains | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First service | May 1, 1971 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Current operator(s) | Amtrak, in partnership with Washington and Oregon Departments of Transportation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ridership | 2,038 daily 792,481 total (FY16) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | www | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Route | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Start | Vancouver, BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stops | 18 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| End | Eugene, OR | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Distance travelled | 467 miles (752 km) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Train number(s) | northbound (even): 500, 502, 504, 506, 508, 516, 518 southbound (odd): 501, 505, 507, 511, 513, 517, 519 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| On-board services | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Class(es) | Business class, Coach class | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Catering facilities | Bistro car | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Observation facilities | Lounge car | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Baggage facilities | Checked baggage available at select stations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rolling stock | Siemens Charger diesel locomotives Talgo Series 8 articulated tilting train sets Non-Powered Control Units (former EMD F40PH locomotives) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operating speed | 79 mph (127 km/h) (top) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track owner(s) | Union Pacific and BNSF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In the fiscal year 2017, Cascades was Amtrak's eighth-busiest route with a total annual ridership of over 810,000.[1] In fiscal year 2018, farebox recovery ratio for the train was 63%.[2]

As of January 2018, 11 trains operate along the corridor each day–two between Vancouver, BC and Seattle, two between Vancouver, BC and Portland, three between Seattle and Portland; one from Portland to Eugene, and three between Eugene and Seattle.[3] Presently, no train travels directly through the entire length of the corridor. For trains that do not travel directly to Vancouver or Eugene, connections are available on Amtrak Thruway Motorcoach services.[3] Additionally, Amtrak Thruway Motorcoach services offer connections to other destinations in British Columbia, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington not on the rail corridor.

History

Passenger train service between Seattle and Portland–the core of what became the Cascades corridor–was operated as a joint partnership by the Northern Pacific, Great Northern, and Union Pacific from 1925 to 1970, with the three railroads cross-honoring tickets on their Seattle-Portland routes. When Great Northern and Northern Pacific were folded into the Burlington Northern in 1970, the reconfigured partnership continued to operate the Seattle-Portland service until the creation of Amtrak in 1971.[4] Service between Vancouver, BC and Seattle was provided via the Great Northern/Burlington Northern International, and between Portland and Eugene by Southern Pacific.

Amtrak took over intercity passenger rail operations from the private railroads on May 1, 1971. Initial service on the Seattle–Portland portion of the corridor consisted of three daily round trips–one long-distance train running all the way to San Diego, along with two corridor trains inherited from Burlington Northern. There was no corridor service south to Eugene, and no service to the Canadian border at all. The trains were unnamed until November 1971, when the two corridor trains were named the Mount Rainier and Puget Sound and the long-distance train became the Coast Starlight.[5]

Passenger rail service to Vancouver, BC was restarted on July 17, 1972, with the inauguration of the Seattle–Vancouver Pacific International, which operated with a dome car (unusual for short runs).[6][7] The train was Amtrak's first international service.[7]

The next major change to service in the corridor came on June 7, 1977, when Amtrak introduced the long-distance Pioneer between Seattle, Portland and Salt Lake City, Utah. To maintain the same level of service between Seattle and Portland, the Puget Sound was eliminated, and the schedule of the Mount Rainier was shifted.[8]:59

The corridor expanded south of Portland to Eugene on August 3, 1980 with the addition of the Willamette Valley, which operated with two daily round trips, financially subsidized by the State of Oregon.

The Pacific International and Willamette Valley struggled to attract riders and were discontinued in September 1981 and December 1981, respectively.[5][9]

This left three trains on the Seattle–Portland corridor: the regional Mount Rainier and the long-distance Pioneer and Coast Starlight. This level of service would remain unchanged for 13 years.

Expansion in the 1990s and 2000s

In 1994, Amtrak began a six-month trial run of modern Talgo equipment over the Seattle–Portland corridor. Amtrak named this service Northwest Talgo, and announced that it would institute a second, conventional train on the corridor (supplementing the Mount Rainier) once the trial concluded. Regular service began on April 1, 1994.

Looking toward the future, Amtrak did an exhibition trip from Vancouver through to Eugene. Amtrak replaced the Northwest Talgo with the Mount Adams on October 30.[10][11] At the same time, the state of Oregon and Amtrak agreed to extend the Mount Rainier to Eugene through June 1995, with Oregon paying two-thirds of the $1.5 million subsidy.[12]

Vancouver service returned on May 26, 1995, when the Mount Baker International began running between Vancouver and Seattle. The state of Washington leased Talgo equipment similar to the demonstrator from 1994.[13][14] The Mount Rainier was renamed the Cascadia in October 1995; the new name reflected the joint Oregon–Washington operations of the train.[15]

A third Seattle–Portland corridor train began in the spring of 1998 with leased Talgo equipment, replacing the discontinued long-distance Pioneer. The other Seattle–Portland/Eugene trains began using Talgo trainsets as well, while the Seattle-Vancouver train used conventional equipment. In preparation for the Vancouver route receiving Talgo equipment as well, Amtrak introduced the temporary Pacific Northwest brand for all four trains, dropping individual names, effective with the spring 1998 timetable.

Amtrak announced the new Amtrak Cascades brand in the fall 1998 timetable; the new equipment began operation in December.[16][17] The full Cascades brand was rolled out on January 12, 1999, following a six-week delay due to an issue with the seat designs on the Talgo trainsets.[18][19] Amtrak extended a second train to Eugene in late 2000.

From the mid-1990s to the May 12, 2008 Amtrak system timetable, full service dining was available on trains going north out of Seattle's King Street Station to Vancouver. The southern trains to Portland briefly had full dining services until the May 16, 1999 system timetable.

In 2004, the Rail Plus program began, allowing cross-ticketing between Sound Transit's Sounder commuter rail and Amtrak between Seattle and Everett on some Cascades trains.[20]

The corridor has continued to grow in recent years, with another Portland–Seattle train arriving in 2006, and the long-awaited through service between Vancouver and Portland, eliminating the need to transfer in Seattle, beginning on August 19, 2009[21] as a pilot project to determine whether a train permanently operating on the route would be feasible. With the Canadian federal government requesting Amtrak to pay for border control costs for the second daily train, the train was scheduled to be discontinued on October 31, 2010. However, Washington State and Canadian officials held discussions in an attempt to continue the service,[22] which resulted in the Canadian government permanently waiving the fee.[23]

Two additional round trips between Seattle and Portland were added on December 18, 2017; an early morning departure from each city and a late evening return, enabling same-day business travel between the two cities.[24][25][26] On the first day of service, a train derailed outside of DuPont, Washington, south of Tacoma.[27]

In March 2020, Amtrak Cascades service north of Seattle was suspended indefinitely after all non-essential travel across the Canadian border was banned in response to the coronavirus pandemic.[28][29]

Rolling stock

.jpg)

Service on the Cascades route is provided using seven articulated trainsets manufactured by Talgo, a Spanish company. These cars are designed to passively tilt into curves, allowing the train to pass through them at higher speeds than a conventional train. The tilting technology reduces travel time between Seattle and Portland by 25 minutes.[30] Current track and safety requirements limit the train's speed to 79 miles per hour (127 km/h), although the trainsets are designed for a maximum design speed of 124 miles per hour (200 km/h).[30]

A typical trainset consists of 12 or 13 cars: one baggage car; two "business class" coaches; one lounge car; one cafe car (also known as the Bistro car); six or seven "coach class" coaches; and one power car (which houses a head-end power generator and other equipment). [31] Trainsets are typically paired with a Siemens Charger locomotive painted in a matching paint scheme. Additionally trainsets without a cab car are paired with a Non-Powered Control Unit (NPCU), an older locomotive with no engine, that is also painted in a matching paint scheme and is used as a cab car.[32]:140

The fleet consists of five Talgo Series VI trainsets built in 1998 and two Talgo Series 8 trainsets built in 2013. The service offered by the different trainset types is similar, but there are some minor differences between the two models. The most notable difference is the older Series VI trainsets have 7-foot-tall (2.1 m) tail fins at both ends of the train that serve as an aesthetic transition from the low-profile trainsets and the larger locomotives.[30] The Series 8 trainsets do not have the tail fins, but instead have a cab built into the power car allowing push-pull operation without a separate control unit. There are also minor differences in the interior appointments.

The Cascades service started in Fall 1998 with four Series VI trainsets, two were owned by the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) and two were owned by Amtrak. Each trainset was built with 12 cars and a six-car spare set, including a baggage car, service car, lounge car, café car and two "coach class" coaches, was also built. The trainsets can hold 304 passengers in 12 cars.

In 1998, Amtrak also purchased an additional Series VI trainset as a demonstrator for potential service between Los Angeles and Las Vegas. This trainset was built with two additional "coach class" coaches, for a total of 14 cars. The demonstration route was not funded and WSDOT purchased the trainset in 2004 to expand service.[31] The purchase also allowed Amtrak and WSDOT to redistribute the "coach class" coaches. By using the two additional coaches from this new trainset and placing the two coaches from the spare set into regular service, the agencies were able to create four 13-car trains and one 12-car train.

In 2013, the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) purchased the two Series 8 trainsets to enable further expansion of services.[33] Each trainset was equipped with 13 cars.

The Cascades equipment is painted in a special paint scheme consisting of colors the agency calls evergreen (dark green), cappuccino (brown), and cream.[30][34] The trainsets are named after mountain peaks in the Pacific Northwest (many in the Cascade Range). The four original Series VI trainsets were named after Mount Baker, Mount Hood, Mount Olympus, and Mount Rainier. The Series VI trainset built to operate between Las Vegas and Los Angeles was renamed the Mount Adams when it was purchased by the state of Washington. This trainset was subsequently destroyed in the December 18, 2017, derailment on the Point Defiance Cutoff. The two Series 8 trainsets are named Mount Bachelor and Mount Jefferson.

In early 2014, the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT), awarded a contract to Siemens USA to manufacture 8 new Siemens Charger locomotives for the Cascades. The order was part of a larger joint purchase between Illinois, California, Michigan, and Missouri. These locomotives were delivered to WSDOT in Summer 2017 and went into service in late 2017.[35][36] The additional locomotives were to have enabled two additional runs to be added as part of the Point Defiance Bypass project (the additional service was suspended and its recommencement has not been announced) and will replace the six EMD F59PHI locomotives leased from Amtrak; these were sold to Metra in early 2018. One SC-44 locomotive was destroyed in the December 18, 2017, derailment on the Point Defiance Cutoff. In the wake of the accident, Amtrak proposed to lease or buy two Talgo trainsets which were originally bought for use in Wisconsin but never operated.[37]

In August 2019, the Federal Railroad Administration awarded WSDOT up to $37.5 million to purchase three new trainsets for the route, allowing the replacement of the older Talgo VI trainsets.[38] The Talgo VI trainsets were withdrawn in July 2020.[39]

Funding

Funding for the route is provided separately by the states of Oregon and Washington, with Union Station in Portland serving as the dividing point between the two. As of July 1, 2006, Washington state has funded four daily round trips between Seattle and Portland. Washington also funds two daily round trips between Seattle and Vancouver, BC. Oregon funds two daily round trips between Eugene and Portland. The seven trainsets are organized into semi-regular operating cycles, but no particular train always has one route.

Local partnerships

As a result of Cascades service being jointly funded by the Washington and Oregon departments of transportation, public transit agencies and local municipalities can offer a variety of discounts, including companion ticket coupons.

- FlexPass and University of Washington UPass holders receive a 15% discount (discount code varies) on all regular Cascades travel. Employers participating in these programs may also receive a limited number of free companion ticket coupons for distribution to employees.[40]

- The Sound Transit RailPlus program allows riders to use weekday Cascades trains between Everett and Seattle with the Sounder commuter rail fare structure.[41]

The Cascades service also benefits from Sound Transit's track upgrades for Sounder service, notably the Point Defiance Bypass project.

Proposed changes

According to its long-range plan, the WSDOT Rail Office plans eventual service of 13 daily round trips between Seattle and Portland and 4–6 round trips between Seattle and Bellingham, with four of those extending to Vancouver, BC.[42] Amtrak Cascades travels along the entirety of the proposed Pacific Northwest High Speed Rail Corridor; the incremental improvements are designed to result in eventual higher-speed service. According to WSDOT, the "hundreds of curves" in the current route and "the cost of acquiring land and constructing a brand new route" make upgrades so cost-prohibitive that, at most, speeds of 110 mph (177 km/h) can be achieved.[43]

The eventual high-speed rail service according to the long-range plan should result in the following travel times:

- Seattle to Portland – 3:30 (2006); 3:20 (after completion of Point Defiance Bypass);[43] 2:30 (planned)

- Seattle to Vancouver BC – 3:55 (2006); 2:45 (planned)

- Vancouver BC to Portland – 7:55 (2009); 5:25 (planned)

In order to increase train speeds and frequency to meet these goals, a number of incremental track improvement projects must be completed. Gates and signals must be improved, some grade crossings must be separated, track must be replaced or upgraded and station capacities must be increased.

In order to extend the second daily Seattle to Bellingham round trip to Vancouver, BNSF was required to make track improvements in Canada, to which the government of British Columbia was asked to contribute financially. On March 1, 2007, an agreement between the province, Amtrak, and BNSF was reached, allowing a second daily train to and from Vancouver.[44] The project involved building an 11,000-foot (3.35 km) siding in Delta, BC at a cost of US$7 million; construction started in 2007 and has been completed.

In December 2008, WSDOT published a mid-range plan detailing projects needed to achieve the midpoint level of service proposed in the long-range plan.[45]

In 2009, Oregon applied for a $2.1 billion Federal grant to redevelop the unused Oregon Electric Railway tracks, parallel to the Cascades' route between Eugene and Portland.[46] But it did not receive the grant. Instead, analysis of alternative routes to enable more passenger trains and higher speeds proceeded. In 2015, the current route, with numerous upgrades, was chosen by the Project Team as the Recommended Preferred Alternative.[47] The Preferred Alternative, if built, would decrease the trip time by 15 minutes from 2 hours and 35 minutes to 2 hours and 20 minutes and increase the number of daily trains from 2 to 6 from Eugene to Portland.[48]

In 2013, travel times between Seattle and Portland remained the same as they had been in 1966, with the fastest trains making the journey in 3 hours 30 minutes.[49][50] WSDOT received more than $800 million in high-speed rail stimulus funds for projects discussed in the mid-range plan, since the corridor is one of the approved high-speed corridors eligible for money from ARRA.[51] The deadline for spending the stimulus funds is September 2017. The schedule was for the Leadership Council to vote on this in December 2015, then a Draft Tier 1 Environmental Impact Statement was to be released in 2016 and hearings held on it, for the Leadership Council to finalize the Recommended Selected Alternative in 2017, then publish the Final Tier 1 EIS and receive the Record of Decision in 2018.[52] Then if funds can be found, design and engineering must be done before any construction can begin.

Accidents and incidents

July 2017 derailment

On July 2, 2017, northbound train 506 derailed while approaching the Chambers Bay drawbridge southwest of Tacoma, Washington. The train was traveling above the speed limit of 40 miles per hour (64 km/h) after passing an "Approach" signal (indicating that it be prepared to stop short of the next signal) at the bridge. As the bridge was raised and open, a device known as a "de-rail" was engaged, used to prevent a train from proceeding and falling in to the water by derailing it beforehand. The incident root cause was human error due to the engineer losing situational awareness. Only minor injuries were sustained due to the low speed at time of event as the engineer did attempt to stop on seeing the bridge up. The train's consist, an Oregon DOT-owned Talgo VIII set, was returned to the Talgo plant in Milwaukee, Wis. for repairs and returned to service in April 2018.[53]

December 2017 derailment

On December 18, 2017, while making the inaugural run on the Point Defiance Bypass, Amtrak Cascades passenger train 501 derailed near Dupont, Washington, killing three passengers.[54][55] The National Transportation Safety Board said in a news conference later that day that the event data recorder showed the speed to be 80 mph, while the speed limit in the area was 30 mph.[56] Positive train control (PTC), a technology meant to help regulate train speed and prevent operator error, was reported to have been installed on the line, but preliminary reports state it was not active.[57] WSDOT announced that it would not resume service until the full implementation of PTC. (Sounder service to Lakewood continued to operate.) Service was then scheduled to restart in early 2019.[58] PTC was activated on the Bypass in March 2019 and the NTSB report was released in May that year, however Cascades service will remain off the bypass indefinitely.[59][60]

Ridership

Total ridership for 2008 was 774,421, the highest annual ridership since inception of the service in 1993.[61] Ridership declined in 2009 to 740,154[62] but rose 13% in fiscal year 2010 to 836,499 riders,[62] and to 847,709 riders in 2011.

Ridership declined steadily between 2011 and 2015, attributed in part to competition from low-cost bus carrier BoltBus, which opened a non-stop Seattle–Portland route in May 2012.[63][64][65] Low gasoline prices and schedule changes due to track construction also contributed to the decline. Ridership rose again in 2016, and is expected to continue rising in 2017 and beyond, after the completion of the Point Defiance Bypass construction project.[66]

Data from the Washington State Department of Transportation:[2][65][67][68][69]

| Year | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ridership | 94,061 | 180,209 | 286,656 | 304,566 | 349,761 | 425,138 | 452,334 | 530,218 | 560,381 | 584,346 | 589,743 | 603,059 |

| YoY Diff. | — | 86,148 | 106,447 | 17,910 | 45,195 | 75,377 | 27,196 | 77,884 | 30,163 | 23,965 | 5,397 | 13,316 |

| YoY Diff. % | — | 91.6% | 59.1% | 6.2% | 14.8% | 21.6% | 6.4% | 17.2% | 5.7% | 4.3% | 0.1% | 2.3% |

| Year | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ridership | 636,092 | 629,996 | 676,765 | 774,531 | 761,610 | 838,251 | 847,709 | 836,000 | 807,000 | 781,000 | 745,000 | 817,000 | 811,000 | 802,000 |

| YoY Diff. | 33,033 | −6,096 | 46,769 | 97,766 | −12,921 | 76,641 | 9,458 | −11,700 | −29,000 | −26,000 | −36,000 | 72,000 | –6,000 | –9,000 |

| YoY Diff. % | 5.5% | −1.0% | 7.4% | 14.4% | −1.7% | 10.1% | 1.1% | −1.4% | −3.5% | −3.2% | −4.6% | 9.7% | –0.7% | –1.1% |

See also

References

- "Amtrak Fact Sheet, Fiscal Year 2017 - State of Washington" (PDF). Amtrak. November 2017. Retrieved March 31, 2019.

- "Amtrak Cascades: 2018 Performance Data Report" (PDF). Washington State Department of Transportation. WSDOT. February 2019. Retrieved March 31, 2019.

- "Amtrak Cascades Schedule" (PDF). Amtrak. January 2, 2018. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- The official guide of the Railways and Steam Navigation Lines of the U.S., Rand McNally & Company, May 1966. The guide shows that the service was operated jointly, some trains using Seattle's King Street Station and the rest Seattle's Union Station.

- Schafer, Mike, Bob Johnston and Kevin McKinney. All Aboard Amtrak. Piscataway, NJ: Railpace Co., 1991

- Zimmermann, Karl. Amtrak at Milepost 10. Park Forest IL: PTJ Publishing, 1981.

- Goldberg, Bruce (1981). Amtrak – the first decade. Silver Spring, MD: Alan Books. pp. 16–17. OCLC 7925036.

- Amtrak (May 1, 1977). "National Train Timetables". Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- Wyant, Dan (December 29, 1981). "Slide closes rail line near Oakridge". The Register-Guard. p. 1A.

- Esteve, Harry (March 31, 1994). "Talgo 200 tantalizes train fans". Eugene Register-Guard. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- Amtrak (October 30, 1994). "Pacific Northwest Corridor". National Timetable. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- Bishoff, Don (November 2, 1994). "Seattle in six, and a nap, too". Eugene Register-Guard. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- "For Riders, Vancouver Train's Just the Ticket". The News Tribune. Tacoma, Washington. May 27, 1995. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- "TRAVEL ADVISORY; Amtrak Resumes Seattle-Vancouver Run". The New York Times. June 11, 1995. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- Amtrak (January 1996). "Pacific Northwest Corridor". National Timetable. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- Bishoff, Don (December 2, 1998). "Budget boosts trains service". Eugene Register-Guard. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- Wade, Betsy (December 13, 1998). "Practical Traveler: On Amtrak, Full Speed Ahead". The New York Times. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- Bailey, Mike (January 15, 1999). "No more clickety-clack: Fast track for Amtrak". The Columbian. p. E1.

- Hicks, Matt (January 9, 1999). "Don't miss the trains: Talgo models make area stop". Statesman Journal. Salem, Oregon. p. C1. Retrieved March 21, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The New Math: Sound Transit + Amtrak Cascades = RailPlus" (Press release). Sound Transit. September 17, 2004.

- "Second Amtrak Cascades train between Seattle and Vancouver, B.C to begin service August 19, 2009" (PDF) (Press release). Amtrak. August 12, 2009. Retrieved July 22, 2010.

- "Washington state working to keep second Vancouver, B.C., Amtrak train". Trains magazine. September 22, 2010. Retrieved September 23, 2010.

- "Second daily Amtrak train to Vancouver, B.C., made permanent". The Seattle Times. August 17, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- Matkin, Janet; LaBoe, Barbara (October 3, 2017). "WSDOT adds two daily Amtrak Cascades roundtrips starting Dec. 18". Washington State Department of Transportation. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- Shaner, Zach (July 7, 2016). "Amtrak Cascades Looks Toward 2017". Seattle Transit Blog. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- Pittman, Travis (December 17, 2017). "New Amtrak Cascades route starts Monday". KING 5 News. Retrieved December 17, 2017.

- Chokshi, Niraj (December 18, 2017). "Amtrak Passenger Train Derails in Washington State". The New York Times.

- "Service Adjustments Due to Coronavirus" (Press release). Amtrak. March 24, 2020. Archived from the original on March 25, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- Dickson, Jane (March 18, 2020). "Canada-U.S. border to close except for essential supply chains". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- "Amtrak Cascades Facts". Archived from the original on July 2, 2017. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- "Trainset Roster". On Track On Line. January 1, 2013. Retrieved June 2, 2013.

- Solomon, Brian (2004). Amtrak. Saint Paul, Minnesota: MBI. ISBN 978-0-7603-1765-5.

- Oregon DOT

- "Amtrak Cascades Train Equipment". Washington State Department of Transportation. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- "Rail - Amtrak Cascades New Locomotives | WSDOT". www.wsdot.wa.gov. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- Lloyd, Sarah Anne (November 20, 2017). "Amtrak Cascades rolls out new locomotives". Curbed Seattle. Retrieved December 17, 2017.

- Federal Railroad Administration (February 1, 2018). "Petition for Waiver of Compliance" (PDF). Federal Register. Government Publishing Office. 83 (22): 4728.

- "U.S. Transportation Secretary Elaine L. Chao Announces $272 Million in 'State of Good Repair' Program Grants" (Press release). Federal Railroad Administration. August 21, 2019.

- "Talgo VI trainsets withdrawn from Amtrak Cascades service". Railway Gazette. July 16, 2020.

- Amtrak Cascades. "Amtrak Cascades - Special Offers". Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- Sound Transit. "Sounder train fares". Archived from the original on October 17, 2011. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- "Long Range Plan for Amtrak Cascades" (PDF). WSDOT. February 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 8, 2009. Retrieved July 7, 2009.

- Schrader, Jordan (May 17, 2011). "Federal money to improve Amtrak Cascades train travel". Seattle Times. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- "WSDOT - Second Amtrak Cascades Train to Canada". Archived from the original on April 12, 2008. Retrieved July 5, 2007.

- "Amtrak Cascades Mid-Range Plan" (PDF). WSDOT. December 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2009. Retrieved July 7, 2009.

- Esteve, Harry (July 25, 2009). "Oregon bids big for faster trains". The Oregonian.

- http://oregonpassengerrail.org/files/library/newsletter/opr-newsletter-fall-2015-final-20151013.pdf

- Tier 1 Draft Environmental Impact Statement (PDF) (Report). Oregon Department of Transportation. October 2018. Retrieved December 27, 2018.

- The Official guide of the Railways and Steam Navigation Lines of the U.S., Rand McNally & Company, May 1966

- Amtrak Winter-Spring Timetable 2013

- "ARRA Funded High Speed Rail". WSDOT. Archived from the original on July 5, 2009. Retrieved July 7, 2009.

- http://oregonpassengerrail.org/page/schedule

- Miller, Susan (December 18, 2017). "Amtrak's Cascades rail lines saw a derailment in July". USA Today. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

- Chokshi, Niraj (December 18, 2017). "Amtrak Train Derailment Leaves Multiple People Dead in Washington State". The New York Times. Retrieved December 18, 2017.

- "Amtrak Cascades Train 501 Derailment" (PDF). Amtrak. December 18, 2017. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- La Corte, Rachel; Flaccus, Gillian; Sisak, Michael (December 19, 2017). "Train speeding 50 mph over limit before deadly derailment in Washington state". News and Record. Associated Press. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- Ostrower, Jon; Sterling, Joe; Ellis, Ralph (December 19, 2017). "At least 3 dead in Amtrak derailment in Washington state, official says". cnn.com. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

- Baker, Mike (December 21, 2017). "Washington state: No passenger trains on Amtrak derailment route until safety systems are in place". The Seattle Times. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- "Positive train control fully activated on Amtrak Cascades corridor, WSDOT says". KIRO 7. March 25, 2019.

- Virgin, Bill (June 12, 2019). "Washington city wants Point Defiance Bypass to stay closed until all recommended safety installations are complete | Trains Magazine". TrainsMag.com. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- Washington State Department of Transportation. "Amtrak Cascades Annual Ridership Report 2008" (PDF). Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- "Amtrak sets new ridership record, thanks passengers for taking the train (link to PDF download)". Amtrak. October 11, 2010. Retrieved November 4, 2010.

- Pucci, Carol (July 7, 2012). "BoltBus gives Amtrak a run for the money on Seattle-Portland travel". The Seattle Times. Retrieved May 3, 2017.

- Cook, John (May 1, 2012). "Seattle to Portland for a $1? That's the promise of BoltBus". GeekWire. Retrieved May 3, 2017.

- Balk, Gene (October 14, 2013). "Amtrak ridership is down in the Northwest–is Bolt Bus to blame?". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on November 10, 2017. Retrieved November 9, 2017.

- Johnson, Graham (April 1, 2016). "Amtrak Cascades ridership declining but state predicts a rebound". KIRO 7. Retrieved May 3, 2017.

- Washington State Department of Transportation (December 2009). "Amtrak Cascades Fourth Quarter and Annual Ridership Report – 2009" (PDF). Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- Washington State Department of Transportation (December 2010). "Amtrak Cascades Quarterly Ridership Report - October to December 2010" (PDF). Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- Washington State Department of Transportation (December 2011). "Amtrak Cascades Quarterly Ridership Report - October to December 2011" (PDF). Retrieved February 11, 2012.

External links

- Amtrak Cascades – Amtrak

- Official website

- Amtrak Cascades Train Equipment (Washington State Department of Transportation)

- 1972 first draft of "Cascades" concept (Oregon Department of Transportation)