Pseudonym

A pseudonym (/ˈsjuːdənɪm/) or alias (/ˈeɪliəs/) is a name that a person or group assumes for a particular purpose, which can differ from their first or true name (orthonym).[1] This differs from a new name that entirely replaces an individual's own. The pseudonym identifies a holder, that is, one or more persons who have but do not disclose their true names (that is, legal identities).[2] Most pseudonym holders use pseudonyms because they wish to remain anonymous, but anonymity is difficult to achieve and often fraught with legal issues.[3] True anonymity requires unlinkability, such that an attacker's examination of the pseudonym holder's message provides no new information about the holder's true name.[4]

Scope

Pseudonyms include stage names and user names, ring names, pen names, nicknames, aliases, superhero or villain identities and code names, gamer identifications, and regnal names of emperors, popes, and other monarchs. Historically, they have sometimes taken the form of anagrams, Graecisms, and Latinisations, although there are many other methods of choosing a pseudonym.[5]

Pseudonyms should not be confused with new names that replace old ones and become the individual's full-time name. Pseudonyms are "part-time" names, used only in certain contexts – to provide a more clear-cut separation between one's private and professional lives, to showcase or enhance a particular persona, or to hide an individual's real identity, as with writers' pen names, graffiti artists' tags, resistance fighters' or terrorists' noms de guerre, and computer hackers' handles. Actors, voice-over artists, musicians, and other performers sometimes use stage names, for example, to better channel a relevant energy, gain a greater sense of security and comfort via privacy, more easily avoid troublesome fans/"stalkers", or to mask their ethnic backgrounds.

In some cases, pseudonyms are adopted because they are part of a cultural or organisational tradition: for example devotional names used by members of some religious institutes, and "cadre names" used by Communist party leaders such as Trotsky and Lenin.

A pseudonym may also be used for personal reasons: for example, an individual may prefer to be called or known by a name that differs from their given or legal name, but is not ready to take the numerous steps to get their name legally changed; or an individual may simply feel that the context and content of an exchange offer no reason, legal or otherwise, to provide their given or legal name.

A collective name or collective pseudonym is one shared by two or more persons, for example the co-authors of a work, such as Carolyn Keene, Ellery Queen, Nicolas Bourbaki, or James S. A. Corey.

Etymology

The term pseudonym is derived from the Greek ψευδώνυμον (pseudṓnymon),[6] literally "false name", from ψεῦδος (pseûdos), "lie, falsehood"[7] and ὄνομα (ónoma), "name".[8] The term alias is a Latin adverb meaning "at another time, elsewhere".[9]

Distinction from allonyms, ghost writers and pseudepigrapha

A pseudonym is distinct from an allonym, which is the (real) name of another person, assumed by the author of a work of art.[10] This may occur when someone is ghostwriting a book or play, or in parody, or when using a "front" name, such as by screenwriters blacklisted in Hollywood in the 1950s and 1960s. See also pseudepigraph, for falsely attributed authorship.

Usage

Name change

Sometimes people change their name in such a manner that the new name becomes permanent and is used by all who know the person. This is not an alias or pseudonym, but in fact a new name. In many countries, including common law countries, a name change can be ratified by a court and become a person's new legal name.

For example, in the 1960s, civil rights campaigner Malcolm X, originally known as Malcolm Little, changed his surname to "X" to represent his unknown African ancestral name that had been lost when his ancestors were brought to North America as slaves. He then changed his name again to Malik El-Shabazz when he converted to Islam.

Likewise some Jews adopted Hebrew family names upon immigrating to Israel, dropping surnames that had been in their families for generations. The politician David Ben-Gurion, for example, was born David Grün in Poland. He adopted his Hebrew name in 1910, when he published his first article in a Zionist journal in Jerusalem.[11]

Many transgender people also choose to adopt a new name, sometimes around the time of their transitioning, to match their desired gender better than their birth name.

Concealing identity

Business

Businesspersons of ethnic minorities in some parts of the world are sometimes advised by an employer to use a pseudonym that is common or acceptable in that area when conducting business, to overcome racial or religious bias.[12]

Criminal activity

Criminals may use aliases, fictitious business names, and dummy corporations (corporate shells) to hide their identity, or to impersonate other persons or entities in order to commit fraud. Aliases and fictitious business names used for dummy corporations may become so complex that, in the words of The Washington Post, "getting to the truth requires a walk down a bizarre labyrinth" and multiple government agencies may become involved to uncover the truth.[13]

Literature

A pen name, or "nom de plume" (French for "pen name"), is a pseudonym (sometimes a particular form of the real name) adopted by an author (or on the author's behalf by their publishers).

Although the term is most frequently used today with regard to identity and the Internet, the concept of pseudonymity has a long history. In ancient literature it was common to write in the name of a famous person, not for concealment or with any intention of deceit; in the New Testament, the second letter of Peter is probably such. A more modern example is all of The Federalist Papers, which were signed by Publius, a pseudonym representing the trio of James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay. The papers were written partially in response to several Anti-Federalist Papers, also written under pseudonyms. As a result of this pseudonymity, historians know that the papers were written by Madison, Hamilton, and Jay, but have not been able to discern with complete accuracy which of the three authored a few of the papers. There are also examples of modern politicians and high-ranking bureaucrats writing under pseudonyms.[14][15]

Some female authors used male pen names, in particular in the 19th century, when writing was a male-dominated profession. The Brontë sisters used pen names for their early work, so as not to reveal their gender (see below) and so that local residents would not know that the books related to people of the neighbourhood. The Brontës used their neighbours as inspiration for characters in many of their books. Anne Brontë's The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848) was published under the name Acton Bell, while Charlotte Brontë used the name Currer Bell for Jane Eyre (1847) and Shirley (1849), and Emily Brontë adopted Ellis Bell as cover for Wuthering Heights (1847). Other examples from the nineteenth-century are the novelist Mary Ann Evans (George Eliot) and the French writer Amandine Aurore Lucile Dupin (George Sand). Pseudonyms may also be used due to cultural or organization or political prejudices.

On the other hand, some 20th and 21st-century male romance novelists have used female pen names.[16] A few examples are Brindle Chase, Peter O'Donnell (as Madeline Brent), Christopher Wood (as Penny Sutton and Rosie Dixon), and Hugh C. Rae (as Jessica Sterling).[16]

A pen name may be used if a writer's real name is likely to be confused with the name of another writer or notable individual, or if the real name is deemed unsuitable.

Authors who write both fiction and non-fiction, or in different genres, may use different pen names to avoid confusing their readers. For example, the romance writer Nora Roberts writes mystery novels under the name J.D. Robb.

In some cases, an author may become better known by his pen name than his real name. A famous example is Samuel Clemens, writing as Mark Twain. The British mathematician Charles Dodgson wrote fantasy novels as Lewis Carroll and mathematical treatises under his own name.

Some authors, such as Harold Robbins, use several literary pseudonyms.[17]

Some pen names have been used for long periods, even decades, without the author's true identity being discovered, as with Elena Ferrante and Torsten Krol.

Some pen names are not strictly pseudonyms, as they are simply variants of the authors' actual names. The authors C.L. Moore and S.E. Hinton were female authors who used the initialled forms of their full names, Moore being Catherine Lucille Moore, writing in the 1930s male-dominated science fiction genre, and Hinton, (author of The Outsiders) Susan Eloise Hinton. Star Trek writer D.C. Fontana (Dorothy Catherine) wrote using her own abbreviated name and under the pen names Michael Richards and J. Michael Bingham. Author V.C. Andrews intended to publish under her given name, Virginia Andrews, but was told that, due to a production error, her first novel was being released under the name of "V.C. Andrews"; later she learned that her publisher had in fact done this deliberately. Joanne Rowling[18] published the Harry Potter series as J.K. Rowling. Rowling also published the Cormoran Strike series, a series of detective novels including The Cuckoo's Calling under the pseudonym "Robert Galbraith".

Winston Churchill wrote as Winston S. Churchill (from his full surname "Spencer-Churchill" which he did not otherwise use) in an attempt to avoid confusion with an American novelist of the same name. The attempt was not wholly successful – the two are still sometimes confused by booksellers.[19][20]

A pen name may be used specifically to hide the identity of the author, as with exposé books about espionage or crime, or explicit erotic fiction. Some prolific authors adopt a pseudonym to disguise the extent of their published output, e. g. Stephen King writing as Richard Bachman. Co-authors may choose to publish under a collective pseudonym, e. g., P. J. Tracy and Perri O'Shaughnessy. Frederic Dannay and Manfred Lee used the name Ellery Queen as a pen name for their collaborative works and as the name of their main character. Asa Earl Carter, a Southern white segregationist affiliated with the KKK, wrote Western books under a fictional Cherokee persona to imply legitimacy and conceal his history.[21]

"Why do authors choose pseudonyms? It is rarely because they actually hope to stay anonymous forever," mused writer and columnist Russell Smith in his review of the Canadian novel Into That Fire by the pseudonymous M.J. Cates.[22]

A famous case in French literature was Romain Gary. Already a well-known writer, he started publishing books as Émile Ajar to test whether his new books would be well received on their own merits, without the aid of his established reputation. They were: Émile Ajar, like Romain Gary before him, was awarded the prestigious Prix Goncourt by a jury unaware that they were the same person. Similarly, TV actor Ronnie Barker submitted comedy material under the name Gerald Wiley.

A collective pseudonym may represent an entire publishing house, or any contributor to a long-running series, especially with juvenile literature. Examples include Watty Piper, Victor Appleton, Erin Hunter, and Kamiru M. Xhan.

Another use of a pseudonym in literature is to present a story as being written by the fictional characters in the story. The series of novels known as A Series Of Unfortunate Events are written by Daniel Handler under the pen name of Lemony Snicket, a character in the series. This applies also to some of the several 18th-century English and American writers who used the name Fidelia.

An anonymity pseudonym or multiple-use name is a name used by many different people to protect anonymity.[23] It is a strategy that has been adopted by many unconnected radical groups and by cultural groups, where the construct of personal identity has been criticised. This has led to the idea of the "open pop star".

Medicine

Pseudonyms and acronyms are often employed in medical research to protect subjects' identities through a process known as de-identification.

Science

Nicolaus Copernicus put forward his theory of heliocentrism in the manuscript Commentariolus anonymously.[24] Sophie Germain and William Sealy Gosset used pseudonyms to publish their work in the field of mathematics.[25][26] Satoshi Nakamoto is a pseudonym of a still unknown author or authors' group behind a white paper about bitcoin.[27][28][29][30] In the field of physics, one case of usage of pseudonyms is denounced.[31] Ignazio Ciufolini is accused of publishing two papers on the scientific preprint archive arXiv.org under pseudonyms, each criticizing one of the rivals to LAGEOS, what is argued to be a form of ventriloquism.[32] Such conduct is a violation of arXiv terms of use.[33][34][32]

Military and paramilitary organizations

In Ancien Régime France, a nom de guerre ("war name") would be adopted by each new recruit (or assigned to them by the captain of their company) as they enlisted in the French army. These pseudonyms had an official character and were the predecessor of identification numbers: soldiers were identified by their first names, their family names, and their noms de guerre (e. g. Jean Amarault dit Lafidélité). These pseudonyms were usually related to the soldier's place of origin (e. g. Jean Deslandes dit Champigny, for a soldier coming from a town named Champigny), or to a particular physical or personal trait (e. g. Antoine Bonnet dit Prettaboire, for a soldier prêt à boire, ready to drink). In 1716, a nom de guerre was mandatory for every soldier; officers did not adopt noms de guerre as they considered them derogatory. In daily life, these aliases could replace the real family name.[35]

Noms de guerre were adopted for security reasons by members of the World War II French resistance and Polish resistance. Such pseudonyms are often adopted by military special-forces soldiers, such as members of the SAS and similar units of resistance fighters, terrorists, and guerrillas. This practice hides their identities and may protect their families from reprisals; it may also be a form of dissociation from domestic life. Some well-known men who adopted noms de guerre include Carlos, for Ilich Ramírez Sánchez; Willy Brandt, Chancellor of West Germany; and Subcomandante Marcos, spokesman of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN). During Lehi's underground fight against the British in Mandatory Palestine, the organization's commander Yitzchak Shamir (later Prime Minister of Israel) adopted the nom de guerre "Michael", in honour of Ireland's Michael Collins.

Revolutionaries and resistance leaders, such as Lenin, Trotsky, Golda Meir, Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque, and Josip Broz Tito, often adopted their noms de guerre as their proper names after the struggle. George Grivas, the Greek-Cypriot EOKA militant, adopted the nom de guerre Digenis (Διγενής). In the French Foreign Legion, recruits can adopt a pseudonym to break with their past lives. Mercenaries have long used "noms de guerre", sometimes even multiple identities, depending on country, conflict and circumstance. Some of the most familiar noms de guerre today are the kunya used by Islamic mujahideen. These take the form of a teknonym, either literal or figurative.

Online activity

Individuals using a computer online may adopt or be required to use a form of pseudonym known as a "handle" (a term deriving from CB slang), "user name", "login name", "avatar", or, sometimes, "screen name", "gamertag" "IGN (In Game (Nick)Name)" or "nickname". On the Internet, pseudonymous remailers use cryptography that achieves persistent pseudonymity, so that two-way communication can be achieved, and reputations can be established, without linking physical identities to their respective pseudonyms. Aliasing is the use of multiple names for the same data location.

More sophisticated cryptographic systems, such as anonymous digital credentials, enable users to communicate pseudonymously (i. e., by identifying themselves by means of pseudonyms). In well-defined abuse cases, a designated authority may be able to revoke the pseudonyms and reveal the individuals' real identity.

Use of pseudonyms is common among professional eSports players, despite the fact that many professional games are played on LAN.[36]

Pseudonymity has become an important phenomenon on the Internet and other computer networks. In computer networks, pseudonyms possess varying degrees of anonymity,[37] ranging from highly linkable public pseudonyms (the link between the pseudonym and a human being is publicly known or easy to discover), potentially linkable non-public pseudonyms (the link is known to system operators but is not publicly disclosed), and unlinkable pseudonyms (the link is not known to system operators and cannot be determined).[38] For example, true anonymous remailer enables Internet users to establish unlinkable pseudonyms; those that employ non-public pseudonyms (such as the now-defunct Penet remailer) are called pseudonymous remailers.

The continuum of unlinkability can also be seen, in part, on Wikipedia. Some registered users make no attempt to disguise their real identities (for example, by placing their real name on their user page). The pseudonym of unregistered users is their IP address, which can, in many cases, easily be linked to them. Other registered users prefer to remain anonymous, and do not disclose identifying information. However, in certain cases, Wikipedia's privacy policy permits system administrators to consult the server logs to determine the IP address, and perhaps the true name, of a registered user. It is possible, in theory, to create an unlinkable Wikipedia pseudonym by using an Open proxy, a Web server that disguises the user's IP address. However, most open proxy addresses are blocked indefinitely due to their frequent use by vandals (see Wikipedia:Blocking policy). Additionally, Wikipedia's public record of a user's interest areas, writing style, and argumentative positions may still establish an identifiable pattern.[39][40]

System operators (sysops) at sites offering pseudonymity, such as Wikipedia, are not likely to build unlinkability into their systems, as this would render them unable to obtain information about abusive users quickly enough to stop vandalism and other undesirable behaviors. Law enforcement personnel, fearing an avalanche of illegal behavior are equally unenthusiastic.[41] Still, some users and privacy activists like the American Civil Liberties Union believe that Internet users deserve stronger pseudonymity so that they can protect themselves against identity theft, illegal government surveillance, stalking, and other unwelcome consequences of Internet use (including unintentional disclosures of their personal information and doxing, as discussed in the next section). Their views are supported by laws in some nations (such as Canada) that guarantee citizens a right to speak using a pseudonym.[42] This right does not, however, give citizens the right to demand publication of pseudonymous speech on equipment they do not own.

Confidentiality

Most Web sites that offer pseudonymity retain information about users. These sites are often susceptible to unauthorized intrusions into their non-public database systems. For example, in 2000, a Welsh teenager obtained information about more than 26,000 credit card accounts, including that of Bill Gates.[43] In 2003, VISA and MasterCard announced that intruders obtained information about 5.6 million credit cards.[44] Sites that offer pseudonymity are also vulnerable to confidentiality breaches. In a study of a Web dating service and a pseudonymous remailer, University of Cambridge researchers discovered that the systems used by these Web sites to protect user data could be easily compromised, even if the pseudonymous channel is protected by strong encryption. Typically, the protected pseudonymous channel exists within a broader framework in which multiple vulnerabilities exist.[45] Pseudonym users should bear in mind that, given the current state of Web security engineering, their true names may be revealed at any time.

Online reputations

Pseudonymity is an important component of the reputation systems found in online auction services (such as eBay), discussion sites (such as Slashdot), and collaborative knowledge development sites (such as Wikipedia). A pseudonymous user who has acquired a favorable reputation gains the trust of other users. When users believe that they will be rewarded by acquiring a favorable reputation, they are more likely to behave in accordance with the site's policies.[46]

If users can obtain new pseudonymous identities freely or at very low cost, reputation-based systems are vulnerable to whitewashing attacks[47] (also called serial pseudonymity), in which abusive users continuously discard their old identities and acquire new ones in order to escape the consequences of their behavior: "On the Internet, nobody knows that yesterday you were a dog, and therefore should be in the doghouse today."[48] Users of Internet communities who have been banned only to return with new identities are called sock puppets.

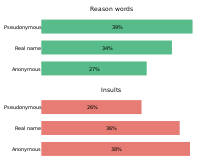

The social cost of cheaply discarded pseudonyms is that experienced users lose confidence in new users,[51] and may subject new users to abuse until they establish a good reputation.[48] System operators may need to remind experienced users that most newcomers are well-intentioned (see, for example, Wikipedia's policy about biting newcomers). Concerns have also been expressed about sock puppets exhausting the supply of easily remembered usernames. In addition a recent research paper demonstrated that people behave in a potentially more aggressive manner when using pseudonyms/nicknames (due to the effects of Online disinhibition effect) as opposed to being completely anonymous.[52][53] In contrast, research by the blog comment hosting service Disqus found pseudonymous users contributed the "highest quantity and quality of comments", where "quality" is based on an aggregate of likes, replies, flags, spam reports, and comment deletions,[49][50] and found that users trusted pseudonyms and real names equally.[54]

Researchers at the University of Cambridge showed that pseudonymous comments tended to be more substantive and engaged with other users in explanations, justifications, and chains of argument, and less likely to use insults, than either fully anonymous or real name comments.[55] Proposals have been made to raise the costs of obtaining new identities (for example, by charging a small fee or requiring e-mail confirmation). Others point out that Wikipedia's success is attributable in large measure to its nearly non-existent initial participation costs.

Privacy

People seeking privacy often use pseudonyms to make appointments and reservations.[56] Those writing to advice columns in newspapers and magazines may use pseudonyms.[57] Steve Wozniak used a pseudonym when attending the University of California, Berkeley after co-founding Apple Computer, because "I knew I wouldn't have time enough to be an A+ student."[58]

Stage names

When used by an actor, musician, radio disc jockey, model, or other performer or "show business" personality a pseudonym is called a stage name, or, occasionally, a professional name, or screen name.

Film, theatre, and related activities

Members of a marginalized ethnic or religious group have often adopted stage names, typically changing their surname or entire name to mask their original background.

Stage names are also used to create a more marketable name, as in the case of Creighton Tull Chaney, who adopted the pseudonym Lon Chaney, Jr., a reference to his famous father Lon Chaney, Sr.

Chris Curtis of Deep Purple fame was christened as Christopher Crummey ("crumby" is UK slang for poor quality). In this and similar cases a stage name is adopted simply to avoid an unfortunate pun.

Pseudonyms are also used to comply with the rules of performing arts guilds (Screen Actors Guild (SAG), Writers Guild of America, East (WGA), AFTRA, etc.), which do not allow performers to use an existing name, in order to avoid confusion. For example, these rules required film and television actor Michael Fox to add a middle initial and become Michael J. Fox, to avoid being confused with another actor named Michael Fox. This was also true of author and actress Fannie Flagg, who chose this pseudonym; her real name, Patricia Neal, being the name of another well-known actress; and British actor Stewart Granger, whose real name was James Stewart. The film-making team of Joel and Ethan Coen, for instance, share credit for editing under the alias Roderick Jaynes.[59]

Some stage names are used to conceal a person's identity, such as the pseudonym Alan Smithee, which was used by directors in the Directors Guild of America (DGA) to remove their name from a film they feel was edited or modified beyond their artistic satisfaction. In theatre, the pseudonyms George or Georgina Spelvin, and Walter Plinge are used to hide the identity of a performer, usually when he or she is "doubling" (playing more than one role in the same play).

David Agnew was a name used by the BBC to conceal the identity of a scriptwriter, such as for the Doctor Who serial City of Death, which had three writers, including Douglas Adams, who was at the time of writing the show's Script Editor.[60] In another Doctor Who serial, The Brain of Morbius, writer Terrance Dicks demanded the removal of his name from the credits saying it could go out under a "bland pseudonym".[61] This ended up as Robin Bland.[61][62]

Music

Musicians and singers can use pseudonyms to allow artists to collaborate with artists on other labels while avoiding the need to gain permission from their own labels, such as the artist Jerry Samuels, who made songs under Napoleon XIV. Rock singer-guitarist George Harrison, for example, played guitar on Cream's song "Badge" using a pseudonym.[63] In classical music, some record companies issued recordings under a nom de disque in the 1950s and 1960s to avoid paying royalties. A number of popular budget LPs of piano music were released under the pseudonym Paul Procopolis. Another example is that Paul McCartney used his fictional name "Bernerd Webb" for Peter and Gordon's song Woman.[64]

Pseudonyms are used as stage names in heavy metal bands, such as Tracii Guns in LA Guns, Axl Rose and Slash in Guns N' Roses, Mick Mars in Mötley Crüe, Dimebag Darrell in Pantera, or C.C. Deville in Poison. Some such names have additional meanings, like that of Brian Hugh Warner, more commonly known as Marilyn Manson: Marilyn coming from Marilyn Monroe and Manson from convicted serial killer Charles Manson. Jacoby Shaddix of Papa Roach went under the name "Coby Dick" during the Infest era. He changed back to his birth name when lovehatetragedy was released.

David Johansen, front man for the hard rock band New York Dolls, recorded and performed pop and lounge music under the pseudonym Buster Poindexter in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The music video for Poindexter's debt single, Hot Hot Hot, opens with a monologue from Johansen where he notes his time with the New York Dolls and explains his desire to create more sophisticated music.

Ross Bagdasarian, Sr., creator of Alvin and the Chipmunks, wrote original songs, arranged, and produced the records under his real name, but performed on them as David Seville. He also wrote songs as Skipper Adams. Danish pop pianist Bent Fabric, whose full name is Bent Fabricius-Bjerre, wrote his biggest instrumental hit "Alley Cat" as Frank Bjorn.

For a time, the musician Prince used an unpronounceable "Love Symbol" as a pseudonym ("Prince" is his actual first name rather than a stage name). He wrote the song "Sugar Walls" for Sheena Easton as "Alexander Nevermind" and "Manic Monday" for The Bangles as "Christopher Tracy". (He also produced albums early in his career as "Jamie Starr").

Many Italian-American singers have used stage names, as their birth names were difficult to pronounce or considered too ethnic for American tastes. Singers changing their names included Dean Martin (born Dino Paul Crocetti), Connie Francis (born Concetta Franconero), Frankie Valli (born Francesco Castelluccio), Tony Bennett (born Anthony Benedetto), and Lady Gaga (born Stefani Germanotta)

In 2009, the British rock band Feeder briefly changed its name to Renegades so it could play a whole show featuring a set list in which 95 per cent of the songs played were from their forthcoming new album of the same name, with none of their singles included. Front man Grant Nicholas felt that if they played as Feeder, there would be uproar over him not playing any of the singles, so used the pseudonym as a hint. A series of small shows were played in 2010, at 250- to 1,000-capacity venues with the plan not to say who the band really are and just announce the shows as if they were a new band.

In many cases, hip-hop and rap artists prefer to use pseudonyms that represents some variation of their name, personality, or interests. Examples include Iggy Azalea (her stage name is a combination of her dog's name, Iggy, and her home street in Mullumbimby, Azalea Street), Ol' Dirty Bastard (known under at least six aliases), Diddy (previously known at various times as Puffy, P. Diddy, and Puff Daddy), Ludacris, Flo Rida (whose stage name is a tribute to his home state, Florida), British-Jamaican hip-hop artist Stefflon Don (real name Stephanie Victoria Allen), LL Cool J, and Chingy. Black metal artists also adopt pseudonyms, usually symbolizing dark values, such as Nocturno Culto, Gaahl, Abbath, and Silenoz. In punk and hardcore punk, singers and band members often replace real names with tougher-sounding stage names such as Sid Vicious (real name John Simon Ritchie) of the late 1970s band Sex Pistols and "Rat" of the early 1980s band The Varukers and the 2000s re-formation of Discharge. The punk rock band The Ramones had every member take the last name of Ramone.

Henry John Deutschendorf Jr., an American singer-songwriter, used the stage name John Denver. The Australian country musician born Robert Lane changed his name to Tex Morton. Reginald Kenneth Dwight legally changed his name in 1972 to Elton John.

See also

- Alter ego

- Anonymity

- Anonymous post

- Anonymous remailer

- Bugō

- Code name

- Confidentiality

- Data haven

- Digital signature

- Friend-to-friend

- Heteronym

- Hypocorism

- John Doe

- List of Latinised names

- List of pseudonyms

- List of pseudonyms used in the American Constitutional debates

- List of stage names

- Mononymous person

- Nym server

- Nymwars

- Onion routing

- Penet.fi

- Pseudepigraphy

- Pseudonymization

- Pseudonymous Bosch

- Pseudonymous remailer

- Public key encryption

- Secret identity

Notes

- Room (2010, 3).

- May, Timothy C. (1991). The Crypto Anarchist Manifesto .

- du Pont, George F. (2001) The Criminalization of True Anonymity in Cyberspace Archived 2006-02-21 at the Wayback Machine 7 Mich. Telecomm. Tech. L. Rev.

- Post, David G. (1996). Pooling Intellectual Capital: Thoughts on Anonymity, Pseudoanonymity, and Limited Liability in Cyberspace Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine. University of Chicago Legal Forum.

- Peschke (2006, vii).

- Harper, Douglas. "pseudonym". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ψεῦδος, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus project

- ὄνομα, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus project

- Cassell's Latin Dictionary, Marchant, J.R.V, & Charles, Joseph F., (Eds.), Revised Edition, 1928

- Turco, Lewis (1999). The Book of Literary Terms: The Genres of Fiction, Drama, Nonfiction, Literary Criticism, and Scholarship. Hanover and London: University Press of New England. p. 182. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

allonym.

- "Biography David Ben-Gurion: For the Love of Zion". Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- Robertson, Nan, The Girls in the Balcony: Women, Men, and The New York Times (N.Y.: Random House, [2nd printing?] 1992 (ISBN 0-394-58452-X)), p. 221. In 1968, one such employer was The New York Times, the affected workers were classified-advertising takers, and the renaming was away from Jewish, Irish, and Italian names to ones "with a WASP flavor".

- The Ruse That Roared, The Washington Post, 5 November 1995, Richard Leiby, James Lileks

- https://www.politico.com/story/2016/09/hillary-clinton-emails-fbi-228607

- http://thehill.com/regulation/energy-environment/297255-former-epa-chief-under-fire-for-new-batch-of-richard-windsor-emails

- Rubin, Harold Francis (1916–), Author Pseudonyms: R. Accessed 27 November 2009.

- "J.K. Rowling". J. K. Rowling. c. 2019. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- The Age 19 October 1940, hosted on Google News. "Two Winston Churchills". Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- My Early Life – 1874–1904, hosted on Google Books (11 May 2010). Oldham. ISBN 9781439125069. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- Carter, Dan T. (4 October 1991). "The Transformation of a Klansman". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- Smith, Russell (19 February 2019). "Review: Into That Fire is promising in its themes and canvas ...". Globe and Mail.

- Home, Stewart (1997). Mind Invaders: A Reader in Psychic Warfare, Cultural Sabotage and Semiotic Terrorism. Indiana University: Serpent's Tail. p. 119. ISBN 1-85242-560-1.

- Oxenham, Simon. "soft question - Pseudonyms of famous mathematicians". MathOverflow. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- Case & Leggett 2005, p. 39.

- "soft question - Pseudonyms of famous mathematicians". MathOverflow. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "The misidentification of Satoshi Nakamoto". theweek.com. 30 June 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- Kharif, Olga (23 April 2019). "John McAfee Vows to Unmask Crypto's Satoshi Nakamoto, Then Backs Off". Bloomberg.

- "Who Is Satoshi Nakamoto, Inventor of Bitcoin? It Doesn't Matter". Fortune. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- Bearman, Sophie (27 October 2017). "Bitcoin's creator may be worth $6 billion — but people still don't know who it is". CNBC. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- Iorio, L. (2014). "Withdrawal: 'A new type of misconduct in the field of the physical sciences: The case of the pseudonyms used by I. Ciufolini to anonymously criticize other people's works on arXiv' by L. Iorio". Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology. 65 (11): 2375. arXiv:1407.2137. doi:10.1002/asi.23238.

- Neuroskeptic. "Science Pseudonyms vs Science Sockpuppets". Discover Magazine. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- Retraction Watch (3 June 2014). "Journal retracts letter accusing physicist of using fake names to criticize papers". Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- Retraction Watch (16 June 2014). "Retraction of letter alleging sock puppetry now cites "legal reasons"". Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- "Home | Historica – Dominion". Historica. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- Cocke, Taylor (26 November 2013). "Why esports needs to ditch online aliases". Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- Froomkin, A. Michael (1995). "Anonymity and Its Enemies (Article 4) Archived 2008-05-25 at the Wayback Machine". Journal of Online Law.

- Pfitzmann, A., and M. Köhntopp (2000). "Anonymity, Unobservability, and Pseudonymity: A Proposal for Terminology". In H. Federrath (ed.), Anonymity (Berlin: Springer-Verlag), pp. 1-9.

- Rao, J.R., and P. Rohatgi (2000). "Can Pseudonyms Really Guarantee Privacy?" Proceedings of the 9th USENIX Security Symposium (Denver, Colorado, Aug. 14-17, 2000).

- Jasmine Novak, Prabhakar Raghavan and Andrew Tomkins (17 May 2004). "AntiAliasing on the Web" (PDF). Association for Computing Machinery Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on World Wide Web. New York, NY, USA. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- Clarke, Roger (1998). "Technological Aspects of Internet Crime Prevention." Archived 2008-08-14 at the Wayback Machine Paper presented at the Australian Institute for Criminology's Conference on Internet Crime (February 16–17, 1998).

- "EFF Press Release: Federal Court Upholds Online Anonymous Speech in 2TheMart.com case". web.archive.org. 20 April 2001. Archived from the original on 11 December 2006. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- Reuters News Service (2000). "Report: Hackers Had Gates' Credit Card Data" (March 26, 2000).

- Katayama, F. (2003) "Hacker accesses 5.6 Million Credit Cards" CNN.com: Technology (February 18, 2003).

- Clayton, R.; Danezis, G.; Kuhn, M. (2001). Real World Patterns of Failure in Anonymity Systems (PDF). Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 2137. pp. 230–244. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.16.7923. doi:10.1007/3-540-45496-9_17. ISBN 978-3-540-42733-9.

- Kollock, P. (1999). "The Production of Trust in Online Markets." Archived 2009-02-26 at the Wayback Machine In E.J. Lawler, M. Macy, S. Thyne, and H.A. Walker (eds.), Advances in Group Processes (Greenwich, CT: JAI Press).

- Feldman, M., S. Papadimitriou, and J. Chuang (2004). "Free-Riding and Whitewashing in Peer-to-Peer Systems." Paper presented at SIGCOMM '04 Workship (Portland, Oregon, Aug. 30-Sept. 3, 2004).

- Friedman, E.; Resnick, P. (2001). "The Social Cost of Cheap Pseudonyms" (PDF). Journal of Economics and Management Strategy. 10 (2): 173–199. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.30.6376. doi:10.1162/105864001300122476. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 November 2008.

- Disqus. "Pseudonyms drive communities". Archived from the original on 16 May 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- Rosen, Rebecca J. (11 January 2012). "Real Names Don't Make for Better Commenters, but Pseudonyms Do". The Atlantic. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- Johnson, D.G.; Miller, K. (1998). "Anonymity, Pseudonymity, and Inescapable Identity on the Net". ACM SIGCAS Computers and Society. 28 (2): 37–38. doi:10.1145/276758.276774.

- Tsikerdekis, Michail (2011). "Engineering anonymity to reduce aggression online". Proceedings of the IADIS International Conference - Interfaces and Human Computer Interaction. Rome, Italy: IADIS - International association for development of the information society. pp. 500–504.

- Tsikerdekis Michail (2012). "The choice of complete anonymity versus pseudonymity for aggression online". EMinds International Journal on Human-Computer Interaction. 2 (8): 35–57.

- Roy, Steve (15 December 2014). "What's In A Name? Understanding Pseudonyms". The Disqus Blog. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- Fredheim, Rolf; Moore, Alfred (4 November 2015). "Talking Politics Online: How Facebook Generates Clicks But Undermines Discussion". SSRN 2686164. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Ryan, Harriet; Yoshino, Kimi (17 July 2009). "Investigators target Michael Jackson's pseudonyms". Latimes.com. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- "Toronto Daily Mail, "Women's Kingdom", "A Delicate Question", April 7, 1883, page 5". Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- Stix, Harriet (14 May 1986). "A UC Berkeley Degree Is Now the Apple of Steve Wozniak's Eye". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- "Roderick Jaynes, Imaginary Oscar Nominee for 'No Country' – Vulture". Nymag.com. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- "BBC – Doctor Who Classic Episode Guide – City of Death – Details". bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- Gallagher, William (27 March 2012). "Doctor Who's secret history of codenames revealed". Radio Times. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2013.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Howe, Walker and Stammers Doctor Who the Handbook: The Fourth Doctor pp. 175–176.

- Winn, John (2009). That Magic Feeling: The Beatles' Recorded Legacy, Volume Two, 1966–1970. Three Rivers Press. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-307-45239-9.

- "45cat - Peter And Gordon - Woman / Wrong From The Start - Capitol - USA - 5579". 45cat. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

Sources

- Peschke, Michael. 2006. International Encyclopedia of Pseudonyms. Detroit: Gale. ISBN 978-3-598-24960-0.

- Room, Adrian. 2010. Dictionary of Pseudonyms: 13,000 Assumed Names and Their Origins. 5th rev. ed. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-0-7864-4373-4.

External links

| Look up pseudonym in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Pseudonym. |

- A site with pseudonyms for celebrities and entertainers

- Another list of pseudonyms

- The U.S. copyright status of pseudonyms

- Anonymity Bibliography Excellent bibliography on anonymity and pseudonymity. Includes hyperlinks.

- Anonymity Network Describes an architecture for anonymous Web browsing.

- Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) Anonymity/Pseudonymity Archive

- The Real Name Fallacy - "Not only would removing anonymity fail to consistently improve online community behavior – forcing real names in online communities could also increase discrimination and worsen harassment." with 30 references