Wuthering Heights

Wuthering Heights is a novel by Emily Brontë published in 1847 under her pseudonym "Ellis Bell". Brontë's only finished novel, it was written between October 1845 and June 1846. Wuthering Heights and Anne Brontë's Agnes Grey were accepted by publisher Thomas Newby before the success of her sister Charlotte's novel Jane Eyre. After Emily's death, Charlotte edited a posthumous second edition in 1850.[1]

_-_Wuthering_Heights%2C_1847.jpg) Title page of the first edition | |

| Author | Emily Brontë |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Tragedy, gothic |

| Published | December 1847 |

| Publisher | Thomas Cautley Newby |

| ISBN | 0-486-29256-8 |

| OCLC | 71126926 |

| 823.8 | |

| LC Class | PR4172 .W7 2007 |

| Text | Wuthering Heights online |

Although Wuthering Heights is now a classic of English literature, contemporaneous reviews were deeply polarised; it was controversial because of its unusually stark depiction of mental and physical cruelty, and it challenged Victorian ideas about religion,[2] morality, class[3] and a woman's place in society. The English poet and painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti, although an admirer of the book, referred to it as "A fiend of a book – an incredible monster [...] The action is laid in hell, – only it seems places and people have English names there."[4]

Wuthering Heights was influenced by Romanticism including the novels of Walter Scott, gothic fiction, and Byron, and the moorland setting is significant.

The novel has inspired many adaptations, including film, radio and television dramatisations; a musical; a ballet; operas; and a hit song.

Plot

Opening

In 1801, Lockwood, the new tenant at Thrushcross Grange in Yorkshire, pays a visit to his landlord, Heathcliff, at his remote moorland farmhouse, Wuthering Heights. There he meets a reserved young woman (later identified as Cathy Linton); Joseph, a cantankerous servant; and Hareton, an uneducated young man who speaks like a servant. Everyone is sullen and inhospitable. Snowed in for the night, he reads some diary entries of a former inhabitant of his room, Catherine Earnshaw, and has a nightmare in which a ghostly Catherine begs to enter through the window. Woken by Lockwood, Heathcliff is troubled.

Lockwood's housekeeper Ellen (Nelly) Dean tells him the story of the strange family.

Nelly's tale

Thirty years earlier, the Earnshaws live at Wuthering Heights with their children, Hindley and Catherine, and a servant — Nelly herself. Returning from a trip to Liverpool, Earnshaw brings a young orphan whom he names Heathcliff and treats as his favourite. His own children he neglects, especially after his wife dies. Hindley beats Heathcliff, who gradually becomes close friends with Catherine.

Hindley departs for university, returning as the new master of Wuthering Heights on the death of his father three years later. He and his new wife Frances allow Heathcliff to stay, but only as a servant.

Heathcliff and Catherine spy on Edgar Linton and his sister Isabella, children who live nearby at Thrushcross Grange. Catherine is attacked by their dog, and the Lintons take her in, sending Heathcliff home. When the Lintons visit, Hindley and Edgar make fun of Heathcliff and a fight ensues. Heathcliff is locked in the attic and vows revenge.

Frances dies after giving birth to a son, Hareton. Two years later, Catherine becomes engaged to Edgar. She confesses to Nelly that she still loves Heathcliff, and will try to help but cannot marry him because of his low social status. Nelly warns her against the plan. Heathcliff overhears part of the conversation and, misunderstanding Catherine's heart, flees the household. Catherine falls ill, distraught.

Edgar and Catherine marry, and three years later Heathcliff unexpectedly returns — now a wealthy gentleman. He encourages Isabella's infatuation with him as a means of revenge on Catherine. Enraged by Heathcliff's constant presence, Edgar cuts off contact. Catherine responds by locking herself in her room and refusing food; pregnant with Edgar's child, she never fully recovers. At Wuthering Heights Heathcliff gambles with Hindley who mortgages the property to him to pay his debts. Heathcliff elopes with Isabella, but the relationship fails and they soon return.

When Heathcliff discovers that Catherine is dying, he visits her in secret. She dies shortly after giving birth to a daughter, Cathy, and Heathcliff rages, calling on her ghost to haunt him for as long as he lives. Isabella flees south where she gives birth to Heathcliff's son, Linton. Hindley dies six months later, leaving Heathcliff as master of Wuthering Heights.

Twelve years later, Isabella is dying and the still-sickly Linton is brought back to live with his uncle Edgar at the Grange, but Heathcliff insists that his son must instead live with him. Cathy and Linton (respectively at the Grange and Wuthering Heights) gradually develop a relationship. Heathcliff schemes to ensure that they marry, and on Edgar's death demands that the couple move in with him. He becomes increasingly wild, and reveals that on the night Catherine died he dug up her grave, and ever since has been plagued by her ghost. When Linton dies, Cathy has no option but to remain at Wuthering Heights.

Having reached the present day, Nelly's tale concludes.

Ending

Lockwood grows tired of the moors and moves away. Eight months later he sees Nelly again and she reports that Cathy has been teaching the still-uneducated Hareton to read. Heathcliff was seeing visions of the dead Catherine; he avoided the young people, saying that he could not bear to see Catherine's eyes, which they both shared, looking at him. He had stopped eating, and some days later was found dead in Catherine's old room.

In the present, Lockwood learns that Cathy and Hareton plan to marry and move to the Grange. Joseph is left to take care of the declining Wuthering Heights. Nelly says that the locals have seen the ghosts of Catherine and Heathcliff wandering abroad together, and hopes they are at peace.

Timeline

| 1500: | The stone above the front door of Wuthering Heights, bearing the name Earnshaw, is inscribed, presumably to mark the completion of the house. |

| 1757: | Hindley Earnshaw born (summer) |

| 1762: | Edgar Linton born |

| 1765: | Catherine Earnshaw born (summer); Isabella Linton born (late 1765) |

| 1771: | Heathcliff brought to Wuthering Heights by Mr Earnshaw (late summer) |

| 1773: | Mrs Earnshaw dies (spring) |

| 1774: | Hindley sent off to university by his father |

| 1775: | Hindley marries Frances; Mr Earnshaw dies and Hindley comes back (October); Heathcliff and Catherine visit Thrushcross Grange for the first time; Catherine remains behind (November), and then returns to Wuthering Heights (Christmas Eve) |

| 1778: | Hareton born (June); Frances dies |

| 1780: | Heathcliff runs away from Wuthering Heights; Mr and Mrs Linton both die |

| 1783: | Catherine has married Edgar (March); Heathcliff comes back (September) |

| 1784: | Heathcliff marries Isabella (February); Catherine dies and Cathy born (20 March); Hindley dies; Linton Heathcliff born (September) |

| 1797: | Isabella dies; Cathy visits Wuthering Heights and meets Hareton; Linton brought to Thrushcross Grange and then taken to Wuthering Heights |

| 1800: | Cathy meets Heathcliff and sees Linton again (20 March) |

| 1801: | Cathy and Linton are married (August); Edgar dies (August); Linton dies (September); Mr Lockwood goes to Thrushcross Grange and visits Wuthering Heights, beginning his narrative |

| 1802: | Mr Lockwood goes back to London (January); Heathcliff dies (April); Mr Lockwood comes back to Thrushcross Grange (September) |

| 1803: | Cathy plans to marry Hareton (1 January) |

Characters

- Heathcliff: An orphan found in Liverpool is taken by Mr Earnshaw to Wuthering Heights, where he is reluctantly cared for by the family and spoiled by his adopted father. He and Catherine grow close, and their love is the central theme of the first volume. His revenge against the man she chooses to marry and its consequences are the central theme of the second volume. Heathcliff has been considered a Byronic hero, but critics have pointed out that he reinvents himself at various points, making his character hard to fit into any single type. He has an ambiguous position in society, and his lack of status is underlined by the fact that "Heathcliff" is both his given name and his surname. The character of Heathcliff may have been inspired by Branwell Brontë. An alcoholic and an opium addict, he would have indeed terrorised Emily and her sister Charlotte during frequent crises of delirium tremens that affected him a few years before his death. Even though Heathcliff has no alcohol or drug problems, the influence of Branwell's character is likely. Hindley Earnshaw, an alcoholic, often seized with madness, also owes something to Branwell.[5] Heathcliff is of dark skin-tone, being described in the book as a "dark-skinned gypsy" and "a little Lascar" – a 19th-century term for Indian sailors.[6] Earnshaw calls him "as dark almost as if it came from the devil",[7] and Nelly Dean asks of him “Who knows but your father was Emperor of China, and your mother an Indian queen?”[8]

- Catherine Earnshaw: First introduced to the reader after her death, through Lockwood's discovery of her diary and carvings. The description of her life is confined almost entirely to the first volume. She seems unsure whether she is, or wants to become, more like Heathcliff, or aspires to be more like Edgar. Some critics have argued that her decision to marry Edgar Linton is allegorically a rejection of nature and a surrender to culture, a choice with unfortunate, fateful consequences for all the other characters.[9] She dies hours after giving birth to her daughter.

- Edgar Linton: Introduced as a child in the Linton family, he resides at Thrushcross Grange. Edgar's style and manners are in sharp contrast to those of Heathcliff, who instantly dislikes him, and of Catherine, who is drawn to him. Catherine marries him instead of Heathcliff because of his higher social status, with disastrous results to all characters in the story. He dotes on his wife and later his daughter.

- Nelly Dean: The main narrator of the novel, Nelly is a servant to three generations of the Earnshaws and two of the Linton family. Humbly born, she regards herself nevertheless as Hindley's foster-sister (they are the same age and her mother is his nurse). She lives and works among the rough inhabitants of Wuthering Heights but is well-read, and she also experiences the more genteel manners of Thrushcross Grange. She is referred to as Ellen, her given name, to show respect, and as Nelly among those close to her. Critics have discussed how far her actions as an apparent bystander affect the other characters and how much her narrative can be relied on.[10]

- Isabella Linton: Is seen only in relation to other characters. She views Heathcliff romantically, despite Catherine's warnings, and becomes an unwitting participant in his plot for revenge against Edgar. Heathcliff marries her but treats her abusively. While pregnant, she escapes to London and gives birth to a son, Linton. She entrusts her son to her brother Edgar when she dies.

- Hindley Earnshaw: Catherine's elder brother, Hindley, despises Heathcliff immediately and bullies him throughout their childhood before his father sends him away to college. Hindley returns with his wife, Frances, after Mr Earnshaw dies. He is more mature, but his hatred of Heathcliff remains the same. After Frances's death, Hindley reverts to destructive behaviour, neglects his son, and ruins the Earnshaw family by drinking and gambling to excess. Heathcliff beats Hindley up at one point after Hindley fails in his attempt to kill Heathcliff with a pistol. He dies less than a year after Catherine, and leaves his son with nothing.

- Hareton Earnshaw: The son of Hindley and Frances, raised at first by Nelly but soon by Heathcliff. Joseph works to instill a sense of pride in the Earnshaw heritage (even though Hareton will not inherit Earnshaw property, because Hindley has mortgaged it to Heathcliff). Heathcliff, in contrast, teaches him vulgarities as a way of avenging himself on Hindley. Hareton speaks with an accent similar to Joseph's, and occupies a position similar to that of a servant at Wuthering Heights, unaware that he has been done out of his inheritance. He can only read his name. In appearance, he reminds Heathcliff of his aunt, Catherine.

- Cathy Linton: The daughter of Catherine and Edgar Linton, a spirited and strong-willed girl unaware of her parents' history. Edgar is very protective of her and as a result she is eager to discover what lies beyond the confines of the Grange. Although one of the more sympathetic characters of the novel, she is also somewhat snobbish towards Hareton and his lack of education. She falls in love with and marries Linton Heathcliff.

- Linton Heathcliff: The son of Heathcliff and Isabella. A weak child, his early years are spent with his mother in the south of England. He learns of his father's identity and existence only after his mother dies, when he is twelve. In his selfishness and capacity for cruelty he resembles Heathcliff; physically, he resembles his mother. He marries Cathy Linton because his father, who terrifies him, directs him to do so, and soon after he dies from a wasting illness associated with tuberculosis.

- Joseph: A servant at Wuthering Heights for 60 years who is a rigid, self-righteous Christian but lacks any trace of genuine kindness or humanity. He speaks a broad Yorkshire dialect and hates nearly everyone in the novel.

- Mr Lockwood: The first narrator, he rents Thrushcross Grange to escape society, but in the end decides society is preferable. He narrates the book until Chapter 4, when the main narrator, Nelly, picks up the tale.

- Frances: Hindley's ailing wife and mother of Hareton Earnshaw. She is described as somewhat silly and is obviously from a humble family. Frances dies not long after the birth of her son.

- Mr and Mrs Earnshaw: Catherine's and Hindley's father, Mr Earnshaw is the master of Wuthering Heights at the beginning of Nelly's story and is described as an irascible but loving and kind-hearted man. He favours his adopted son, Heathcliff, which causes trouble in the family. In contrast, his wife mistrusts Heathcliff from their first encounter.

- Mr and Mrs Linton: Edgar's and Isabella's parents, they educate their children in a well-behaved and sophisticated way. Mr Linton also serves as the magistrate of Gimmerton, as his son does in later years.

- Dr Kenneth: The longtime doctor of Gimmerton and a friend of Hindley's who is present at the cases of illness during the novel. Although not much of his character is known, he seems to be a rough but honest person.

- Zillah: A servant to Heathcliff at Wuthering Heights during the period following Catherine's death. Although she is kind to Lockwood, she doesn't like or help Cathy at Wuthering Heights because of Cathy's arrogance and Heathcliff's instructions.

- Mr Green: Edgar's corruptible lawyer who should have changed Edgar's will to prevent Heathcliff from gaining Thrushcross Grange. Instead, Green changes sides and helps Heathcliff to inherit the Grange as his property.

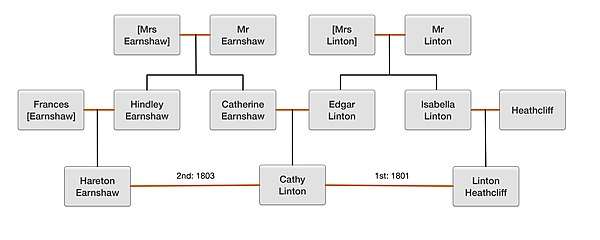

Family relationships map

Publication

1847 edition

The original text, as published by Thomas Cautley Newby in 1847, is available online in two parts.[11][12]

The novel was first published together with Anne Brontë's Agnes Grey in a three-volume format: Wuthering Heights occupied the first two volumes, while Agnes Grey made up the third.

1850 edition

In 1850, when a second edition of Wuthering Heights was due, Charlotte Brontë edited the original text, altering punctuation, correcting spelling errors and making Joseph's thick Yorkshire dialect less opaque. Writing to her publisher, W S Williams, she mentioned that "It seems to me advisable to modify the orthography of the old servant Joseph's speeches; for though, as it stands, it exactly renders the Yorkshire dialect to a Yorkshire ear, yet I am sure Southerns must find it unintelligible; and thus one of the most graphic characters in the book is lost on them." An essay written by Irene Wiltshire on dialect and speech in the novel examines some of the changes Charlotte made.[1]

Critical response

Early reviews (1847–1848)

Early reviews of Wuthering Heights were mixed in their assessment. While most critics at the time recognised the power and imagination of the novel, they were also baffled by the storyline and found the characters prone to savagery and selfishness.[13] Published in 1847, at a time when the background of the author was deemed to have an important impact on the story itself, many critics were also intrigued by the authorship of the novels. Henry Chorley of the Athenæum said that it was a "disagreeable story" and that the "Bells" (Brontës) "seem to affect painful and exceptional subjects".

The Atlas review called it a "strange, inartistic story," but commented that every chapter seems to contain a "sort of rugged power." Atlas summarised the novel by writing: "We know nothing in the whole range of our fictitious literature which presents such shocking pictures of the worst forms of humanity. There is not in the entire dramatis persona, a single character which is not utterly hateful or thoroughly contemptible ... Even the female characters excite something of loathing and much of contempt. Beautiful and loveable in their childhood, they all, to use a vulgar expression, "turn out badly"."[14]

Graham's Lady Magazine wrote "How a human being could have attempted such a book as the present without committing suicide before he had finished a dozen chapters, is a mystery. It is a compound of vulgar depravity and unnatural horrors."[14]

The American Whig Review wrote "Respecting a book so original as this, and written with so much power of imagination, it is natural that there should be many opinions. Indeed, its power is so predominant that it is not easy after a hasty reading to analyze one's impressions so as to speak of its merits and demerits with confidence. We have been taken and carried through a new region, a melancholy waste, with here and there patches of beauty; have been brought in contact with fierce passions, with extremes of love and hate, and with sorrow that none but those who have suffered can understand. This has not been accomplished with ease, but with an ill-mannered contempt for the decencies of language, and in a style which might resemble that of a Yorkshire farmer who should have endeavored to eradicate his provincialism by taking lessons of a London footman. We have had many sad bruises and tumbles in our journey, yet it was interesting, and at length we are safely arrived at a happy conclusion."[15]

Douglas Jerrold's Weekly Newspaper wrote "Wuthering Heights is a strange sort of book,—baffling all regular criticism; yet, it is impossible to begin and not finish it; and quite as impossible to lay it aside afterwards and say nothing about. In Wuthering Heights the reader is shocked, disgusted, almost sickened by details of cruelty, inhumanity, and the most diabolical hate and vengeance, and anon come passages of powerful testimony to the supreme power of love – even over demons in the human form. The women in the book are of a strange fiendish-angelic nature, tantalising, and terrible, and the men are indescribable out of the book itself. Yet, towards the close of the story occurs the following pretty, soft picture, which comes like the rainbow after a storm ... We strongly recommend all our readers who love novelty to get this story, for we can promise them that they never have read anything like it before. It is very puzzling and very interesting, and if we had space we would willingly devote a little more time to the analysis of this remarkable story, but we must leave it to our readers to decide what sort of book it is."[16]

New Monthly Magazine wrote "Wuthering Heights, by Ellis Bell, is a terrific story, associated with an equally fearful and repulsive spot ... Our novel reading experience does not enable us to refer to anything to be compared with the personages we are introduced to at this desolate spot – a perfect misanthropist's heaven."[16]

Tait's Edinburgh Magazine wrote "This novel contains undoubtedly powerful writing, and yet it seems to be thrown away. Mr Ellis Bell, before constructing the novel, should have known that forced marriages, under threats and in confinement are illegal, and parties instrumental thereto can be punished. And second, that wills made by young ladies' minors are invalid. The volumes are powerfully written records of wickedness and they have a moral – they show what Satan could do with the law of Entail."[16]

Examiner wrote "This is a strange book. It is not without evidences of considerable power: but, as a whole, it is wild, confused, disjointed, and improbable; and the people who make up the drama, which is tragic enough in its consequences, are savages ruder than those who lived before the days of Homer."[16]

Literary World wrote "In the whole story not a single trait of character is elicited which can command our admiration, not one of the fine feelings of our nature seems to have formed a part in the composition of its principal actors. In spite of the disgusting coarsness of much of the dialogue, and the improbabilities of much of the plot, we are spellbound."[17]

G.H. Lewes, in Leader, shortly after Emily's death, wrote: "Curious enough is to read Wuthering Heights and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, and remember that the writers were two retiring, solitary, consumptive girls! Books, coarse even for men, coarse in language and coarse in conception, the coarseness apparently of violence and uncultivated men – turn out to be the productions of two girls living almost alone, filling their loneliness with quiet studies, and writing their books from a sense of duty, hating the pictures they drew, yet drawing them with austere conscientiousness! There is matter here for the moralist or critic to speculate on".[18]

A few years later, the English poet and painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti, although an admirer of the book, referred to it as "A fiend of a book – an incredible monster [...] The action is laid in hell, – only it seems places and people have English names there."[4]

Setting

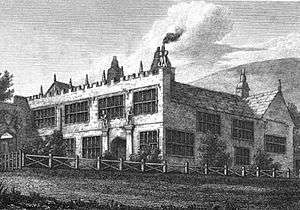

The first description of Wuthering Heights, an old house high on moorland in Yorkshire, is provided by the tenant Lockwood:

Wuthering Heights is the name of Mr. Heathcliff's dwelling, "wuthering" being a significant provincial adjective, descriptive of the atmospheric tumult to which its station is exposed in stormy weather. Pure, bracing ventilation they must have up there at all times, indeed. One may guess the power of the north wind blowing over the edge by the excessive slant of a few stunted firs at the end of the house, and by a range of gaunt thorns all stretching their limbs one way, as if craving alms of the sun.[19]

Wuthering Heights is associated with Heathcliff "who represents the savage forces in human beings which civilization attempts vainly to eliminate"; this wild place stands in contrast with the nearby "'civilized' household of Thrushcross Grange".[20]

Inspiration for locations

There are several theories about which real building or buildings (if any) may have inspired Wuthering Heights. One common candidate is Top Withens, a ruined farmhouse in an isolated area near the Haworth Parsonage, although its structure does not match that of the farmhouse described in the novel.[21] Top Withens was first suggested as the model by Ellen Nussey, a friend of Charlotte Brontë, to Edward Morison Wimperis, an artist who was commissioned to illustrate the Brontë sisters' novels in 1872.[22]

The second possibility is High Sunderland Hall, near Halifax, West Yorkshire, now demolished.[21] This Gothic edifice was located near Law Hill, where Emily worked briefly as a governess in 1838. While it was perhaps grander than Wuthering Heights, the hall had grotesque embellishments of griffins and misshapen nude males similar to those described by Lockwood in Chapter 1 of the novel.

The inspiration for Thrushcross Grange has long been traced to Ponden Hall, near Haworth, which is very small. Shibden Hall, near Halifax, is perhaps more likely.[23], as mentioned by Ian Jacks in the Explanatory Notes to the 1976 edition of the novel.[24] The Thrushcross Grange that Emily describes is rather unusual. It sits within an enormous park, as does Shibden Hall. By comparison, the park at Chatsworth (the home of the Duke of Devonshire) is over 2 miles (3.2 km) long but, as the house sits near the middle, it is no more than 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from the lodge to the house. Considering that Edgar Linton apparently does not even have a title, this seems unlikely.

Point of view

Most of the novel is the story told by housekeeper Nelly Dean to Lockwood, though the novel "uses several narrators (in fact, five or six) to place the story in perspective, or in a variety of perspectives".[25] Emily Brontë uses this frame story technique to narrate most of the story. Thus, for example, Lockwood, the first narrator of the story, tells the story of Nelly, who herself tells the story of another character.[26] The use of a character, like Nelly Dean is "a literary device, a well-known convention taken from the Gothic novel, the function of which is to portray the events in a more mysterious and exciting manner".[27]

Thus the point of view comes

from a combination of two speakers who outline the events of the plot within the framework of a story within a story. The frame story is that of Lockwood, who informs us of his meeting with the strange and mysterious "family" living in almost total isolation in the stony uncultivated land of northern England. The inner story is that of Nelly Dean, who transmits to Lockwood the history of the two families during the last two generations. Nelly Dean examines the events retrospectively and attempts to report them as an objective eyewitness to Lockwood.[28]

Critics have questioned the reliability of the two main narrators.[28] The author has been described as sarcastic "toward Lockwood—who fancies himself a world-weary romantic but comes across as an effete snob", and there are "subtler hints that Nelly’s perspective is influenced by her own biases".[29]

The narrative also includes an excerpt from Catherine Earnshaw’s old diary, and mini-narrations by Heathcliff, Isabella, and another servant.[29]

Romance tradition

Emily Brontë wrote in the romance tradition of the novel[30] that Walter Scott defined, as "a fictitious narrative in prose or verse; the interest of which turns upon marvellous and uncommon incidents".[31] cited in [32] Scott distinguished the romance from the novel, where (as he saw it) "events are accommodated to the ordinary train of human events and the modern state of society".[33] Scott describes romance as a "kindred term" to novel. However, romances like Wuthering Heights,[34] Scotts own historical romances[35] and, for example, Moby Dick[36] are often referred to as novels. Other European languages do not distinguish between romance and novel: "a novel is le roman, der Roman, il romanzo, en roman".[37] This sort of romance is different from the genre fiction love romance or romance novel.

Emily Brontë's approach to the novel form was influenced, in addition to Scott, especially by the Gothic novel, and, in what is usually considered the first gothic novel, The Castle of Otranto (1764) Horace Walpole's declared aim was to combine elements of the medieval romance, which he deemed too fanciful, and the modern novel, which he considered to be too confined to strict realism.[38]

Influences

The periodicals that their father read, the Leeds Intelligencer and Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, were a major source of information for his children.[39] Blackwood's Magazine in particular, was not only the source of their knowledge of world affairs, but also provided material for the Brontës' early writing.[40] It is quite likely that Emily was aware of the debate on evolution, even if the great theses of Charles Darwin were not made public until eleven years after his death. This debate had been launched in 1844 by Robert Chambers and raised the questions of the existence of divine providence, the idea of the violence which underlies the universe and of the relationships between living beings [41].

Among other influences was the Romantic movement that includes the Gothic novel, the novels of Walter Scott,[42] and the poetry of Byron. From 1833, Charlotte and Branwell's Angrian tales begin to feature Byronic heroes who have a strong sexual magnetism and passionate spirit, and demonstrate arrogance and even black-heartedness. They had discovered the poet in an article in Blackwood's Magazine from August 1825; he had died the previous year. From this moment, the name Byron became synonymous with all the prohibitions and audacities as if it had stirred up the very essence of the rise of those forbidden things.[43] The influence of Byronic Romanticism is apparent and Wuthering Heights transports the Gothic to the forbidding Yorkshire Moors and features ghostly apparitions and a Byronic hero in the person of the demonic Heathcliff.

The Brontës' fiction is seen by some feminist critics as prime examples of Female Gothic, exploring woman's entrapment within domestic space and subjection to patriarchal authority and the transgressive and dangerous attempts to subvert and escape such restriction. Emily's Cathy and Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre are both examples of female protagonists in such a role.[44]

Emily also knew Greek tragedies, was a good Latinist, and possessed an exceptional classical culture in a woman of the time. [45][46] She was also influenced by the poetry of Milton and Shakespeare;[47] there are echoes of King Lear as well as Romeo and Juliet.[48]

Gothic novel

Ellen Moers, in Literary Women, developed a feminist theory that connects women writers, including Emily Brontë, with gothic fiction.[34] Catherine Earnshaw has been identified by some critics as a type of gothic demon, because she "shape-shifts" in order to marry Edgar Linton, by assuming a domesticity that is contrary to her true nature.[49] It has also been suggested that Catherine's relationship with Heathcliff conforms to the "dynamics of the Gothic romance, in that the woman falls prey to the more or less demonic instincts of her lover, suffers from the violence of his feelings, and at the end is entangled by his thwarted passion".[50]

At one stage Heathcliff is described as a vampire, and it has been suggested that both he and Catherine are in fact meant to be seen as vampire-like personalities.[51][52]

Themes

Morality

Some critics viewed the novel with suspicion because of its outrageous violence and immorality – surely, the critics wrote, a work of a man with a depraved mind.[53]

Love

According to 2007 British poll Wuthering Heights is the greatest love story of all time – "Yet some of the novel’s admirers consider it not a love story at all but an exploration of evil and abuse".[29] Feminist critics argue that reading of Wuthering Heights as a love story not only "romanticizes abusive men and toxic relationships but goes against Brontë’s clear intent".[29]

While a "passionate, doomed, death-transcending relationship between Heathcliff and Catherine Earnshaw Linton forms the core of the novel", Wuthering Heights consistently subverts the romantic narrative. Our first encounter with Heathcliff shows him to be a nasty bully. Later, Brontë puts in Heathcliff’s mouth an explicit warning not to turn him into a Byronic hero: After ... Isabella elop[es] with him, he sneers that she did so “under a delusion . . . picturing in me a hero of romance.[29]

References in culture

Adaptations

Film and TV

The earliest known film adaptation of Wuthering Heights was filmed in England in 1920 and was directed by A. V. Bramble. It is unknown if any prints still exist.[54] The most famous is 1939's Wuthering Heights, starring Laurence Olivier and Merle Oberon and directed by William Wyler. This acclaimed adaptation, like many others, eliminated the second generation's story (young Cathy, Linton and Hareton) and is rather inaccurate as a literary adaptation. It won the 1939 New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Film and was nominated for the 1939 Academy Award for Best Picture.

In 1958, an adaptation aired on CBS television as part of the series DuPont Show of the Month starring Rosemary Harris as Cathy and Richard Burton as Heathcliff.[55] The BBC produced a television dramatisation in 1967 starring Ian McShane and Angela Scoular.

The 1970 film with Timothy Dalton as Heathcliff is the first colour version of the novel. It has gained acceptance over the years although it was initially poorly received. The character of Hindley is portrayed much more sympathetically, and his story-arc is altered. It also subtly suggests that Heathcliff may be Cathy's illegitimate half-brother.

In 1978, the BBC produced a five-part TV serialisation of the book starring Ken Hutchinson, Kay Adshead and John Duttine, with music by Carl Davis; it is considered one of the most faithful adaptations of Emily Brontë's story.

There is also a 1985 French film adaptation, Hurlevent by Jacques Rivette.

The 1992 film Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights starring Ralph Fiennes and Juliette Binoche is notable for including the oft-omitted second generation story of the children of Cathy, Hindley and Heathcliff.

More recent film or TV adaptations include ITV's 2009 two-part drama series starring Tom Hardy, Charlotte Riley, Sarah Lancashire, and Andrew Lincoln,[56] and the 2011 film starring Kaya Scodelario and James Howson and directed by Andrea Arnold.

Adaptations which place the story in a new setting include the 1954 adaptation, retitled Abismos de Pasion, directed by Spanish filmmaker Luis Buñuel and set in Catholic Mexico, with Heathcliff and Cathy renamed Alejandro and Catalina. In Buñuel's version Heathcliff/Alejandro claims to have become rich by making a deal with Satan. The New York Times reviewed a re-release of this film as "an almost magical example of how an artist of genius can take someone else's classic work and shape it to fit his own temperament without really violating it," noting that the film was thoroughly Spanish and Catholic in its tone while still highly faithful to Brontë.[57] Yoshishige Yoshida's 1988 adaptation also has a transposed setting, this time to medieval Japan. In Yoshida's version, the Heathcliff character, Onimaru, is raised in a nearby community of priests who worship a local fire god. Filipino director Carlos Siguion-Reyna made a film adaptation titled Hihintayin Kita sa Langit (1991). The screenplay was written by Raquel Villavicencio. It starred Richard Gomez as Gabriel (Heathcliff) and Dawn Zulueta as Carmina (Catherine). It became a Filipino film classic.[58] In 2003, MTV produced a poorly reviewed version set in a modern California high school.

The 1966 Indian film Dil Diya Dard Liya is based upon this novel. The film is directed by Abdul Rashid Kardar and Dilip Kumar. The film stars Dilip Kumar, Waheeda Rehman, Pran, Rehman, Shyama and Johnny Walker. The music is by Naushad. Although it did not fare as well as other movies of Dilip Kumar, it was well received by critics.

Theatre

The novel has been popular in opera and theatre, including operas written by Bernard Herrmann, Carlisle Floyd, and Frédéric Chaslin (most cover only the first half of the book) and a musical by Bernard J. Taylor.

Literature

In 2011, a graphic novel version was published by Classical Comics.[59] It was adapted by Scottish writer Sean Michael Wilson and hand painted by comic book veteran artist John M Burns. This version, which stays close to the original novel, received a nomination for the Stan Lee Excelsior Awards, elected by pupils from 170 schools in the United Kingdom.

Works inspired by

Music

Kate Bush's song "Wuthering Heights" is most likely the best-known creative work inspired by Brontë's story that is not properly an "adaptation". Bush wrote and released the song when she was 18 and chose it as the lead single in her debut album (despite the record company preferring another track as the lead single). It was primarily inspired by the Olivier–Oberon film version, which deeply affected Bush in her teenage years. The song is sung from Catherine's point of view as she pleads at Heathcliff's window to be admitted. It uses quotations from Catherine, both in the chorus ("Let me in! I'm so cold!") and the verses, with Catherine's admitting she had "bad dreams in the night". Critic Sheila Whiteley wrote that the ethereal quality of the vocal resonates with Cathy's dementia, and that Bush's high register has both "childlike qualities in its purity of tone" and an "underlying eroticism in its sinuous erotic contours".[60] Singer Pat Benatar also released the song in 1980 on the "Crimes of Passion" album. Brazilian heavy metal band Angra released a version of Bush's song on its debut album Angels Cry, in 1993.[61]A 2018 cover of Bush's "Wuthering Heights" by EURINGER adds electropunk elements.[62]

Wind & Wuthering (1976) by English rock band Genesis alludes to the Brontë novel not only in the album's title but also in the titles of two of its tracks, "Unquiet Slumbers for the Sleepers..." and "...In That Quiet Earth". Both titles refer to the closing lines in the novel.

Songwriter Jim Steinman said that he wrote the song "It's All Coming Back to Me Now" "while under the influence of Wuthering Heights". He said that the song was "about being enslaved and obsessed by love" and compared it to "Heathcliffe digging up Kathy's corpse and dancing with it in the cold moonlight".[63]

The song "Cath" by indie rock band Death Cab for Cutie was inspired by Wuthering Heights.

The song "Cover My Eyes (Pain and Heaven)" by the band Marillion includes the line "Like the girl in the novel in the wind on the moors".

The song "Emily" by folk artist Billie Marten is written from Brontë's perspective. Marten wrote the song while studying Wuthering Heights.

Literature

Mizumura Minae's A True Novel (Honkaku shosetsu) (2002) is inspired by Wuthering Heights and might be called an adaptation of the story in a post-World War II Japanese setting.[64]

In Jane Urquhart's Changing Heaven, the novel Wuthering Heights, as well as the ghost of Emily Brontë, feature as prominent roles in the narrative.

In her 2019 novel, The West Indian, Valerie Browne Lester imagines an origin story for Heathcliff in 1760s Jamaica.[65]

Canadian author Hilary Scharper's ecogothic novel Perdita (2013) was deeply influenced by Wuthering Heights, namely in terms of the narrative role of powerful, cruel and desolate landscapes.[66]

The poem "Wuthering" (2017) by Tanya Grae uses Wuthering Heights as an allegory.[67]

Maryse Condé's Windward Heights (La migration des coeurs) (1995) is a reworking of Wuthering Heights set in Cuba and Guadaloupe at the turn of the 20th century,[68] which Condé stated she intended as an homage to Brontë.[69]

References

- Wiltshire, Irene (March 2005). "Speech in Wuthering Heights: Joseph's Dialect and Charlotte's Emendations" (PDF). Brontë Studies. 30. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2013.

- Nussbaum, Martha Craven (1996). "Wuthering Heights: The Romantic Ascent". Philosophy and Literature. 20: 20 – via Project Muse.

- Eagleton, Terry (2005). Myths of Power. A Marxist Study of the Brontës. London: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-4697-3.

- Rossetti, Dante Gabriel (1854). "Full text of "Letters of Dante Gabriel Rossetti to William Allingham, 1854–1870"".

- Mohrt, Michel (1984). Preface. Les Hauts de Hurle-Vent [Wuthering Heights]. By Brontë, Emily (in French). Le Livre de Poche. pp. 7, 20. ISBN 978-2-253-00475-2.

- Onanuga, Tola (21 October 2011). "Wuthering Heights realises Brontë's vision with its dark-skinned Heathcliff". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- Brontë, Emily. Wuthering Heights. p. Chapter 4. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- Brontë, Emily. Wuthering Heights. p. chapter VII, p 4. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- Gilbert, Sandra M. and Susan Gubar. The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Imagination. New Haven: Yale UP, 2000.

- Hafley, James (December 1958). "The Villain in "Wuthering Heights"" (PDF). Nineteenth-Century Fiction. 13 (3): 199–215. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2010.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Brontë, Emily (1847). "Wuthering Heights: A Novel". Thomas Cautley Newby. Retrieved 13 August 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- Brontë, Emily (1847). "Wuthering Heights: A Novel". Thomas Cautley Newby. Retrieved 13 August 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- Joudrey, Thomas J (2015). "'Well, we must be for ourselves in the long run': Selfishness and Sociality in Wuthering Heights". Nineteenth-Century Literature. 70 (2): 165–93.

- Collins, Nick (22 March 2011). "How Wuthering Heights caused a critical stir when first published in 1847". The Telegraph.

- "The American Whig Review". June 1848.

- "Contemporary Reviews of 'Wuthering Heights', 1847-1848". Wuthering Heights UK.

- Haberlag, Berit (12 July 2005). Reviews of "Wuthering Heights". GRIN Verlag. ISBN 978-3638395526.

- Allott 1995, p. 292

- Brontë, Emily (1998). Wuthering Heights. Oxford World's Classics. Oxford University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0192100276.

- Wynne-Davies, Marion, ed. (1990). "Wuthering Heights". The Bloomsbury Guide to English Literature. Toronto: Prentice Hall. pp. 1032–3. ISBN 978-0136896623.

- Thompson, Paul (June 2009). "Wuthering Heights: The Home of the Earnshaws". Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- Thompson, Paul (June 2009). "The Inspiration for the Wuthering Heights Farmhouse?". Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- Barnard, Robert (2000). Emily Brontë. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195216561.

- Brontë 1976, p. Explanatory notes

- Langman, F H (July 1965). "Wuthering Heights". Essays in Criticism. XV (3): 294–312.

- Las Vergnas, Raymond (1984). "Commentary". Les Hauts de Hurle-Vent. By Brontë, Emily. Le Livre de Poche. pp. 395, 411. ISBN 978-2-253-00475-2.

- Shumani 1973, p. 452 footnote 1

- Shumani 1973, p. 449

- Young, Cathy (26 August 2018). "Emily Brontë at 200: Is Wuthering Heights a Love Story?". Washington Examiner.

- Doody 1997, p. 1

- Scott 1834, p. 129

- Manning 1992, p. xxv

- Scott 1834, p. 129

- Moers 1978

- Manning 1992, pp. xxv-xxvii

- McCrum, Robert (12 January 2014). "The Hundred best novels: Moby Dick". The Observer.

- Doody 1997, p. 15

- Punter, David (2004). The Gothic. London: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 178.

- Drabble 1996, p. 136

- Macqueen, James (June 1826). "Geography of Central Africa. Denham and Clapperton's Journals". Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine. 19:113: 687–709.

- An excellent analysis of this aspect is offered in Davies, Stevie, Emily Brontë: Heretic. London: The Women's Press, 1994, ISBN 978-0704344013.

- Elizabeth Gaskell, The Life of Charlotte Brontë, London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1857, p.104.

- Gérin, Winifred (1966). "Byron's influence on the Brontës". Keats-Shelley Memorial Bulletin. 17.

- Jackson, Rosemary (1981). Fantasy: The Literature of Subversion. Routledge. pp. 123–29. ISBN 978-0415025621.

- Chitham, Edward (1998). The Genesis of Wuthering Heights: Emily Brontë at Work. London: Macmillan.

- Hagan & Wells 2008, p. 84

- Allott 1995, p. 446

- Hagan & Wells 2008, p. 82

- Beauvais, Jennifer (November 2006). "Domesticity and the Female Demon in Charlotte Dacre's Zofloya and Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights". Romanticism on the Net (44). doi:10.7202/013999ar.

- Ceron, Cristina (9 March 2010). "Emily and Charlotte Brontë's Re-reading of the Byronic hero". Revue LISA/LISA e-journal, Writers, writings, Literary studies, document 2 (in French). doi:10.4000/lisa.3504.

- Reed, Toni (30 July 1988). Demon-lovers and Their Victims in British Fiction. University Press of Kentucky. p. 70. ISBN 0813116635. Retrieved 30 July 2018 – via Internet Archive.

Wuthering Heights vampire.

- Senf, Carol A (1 February 2013). The Vampire in Nineteenth Century English Literature. University of Wisconsin Pres. ISBN 978-0-299-26383-6. Retrieved 30 July 2018 – via Google Books.

- Barker, Juliet R V (1995). The Brontës. London: Phoenix House. pp. 539–542. ISBN 1-85799-069-2.

- Wuthering Heights (1920 film) on IMDb

- Schulman, Michael (6 December 2019). "Found! A Lost TV Version of Wuthering Heights". The New Yorker. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- Wuthering Heights 2009(TV)) on IMDb

- Canby, Vincent (27 December 1983). "Abismos de Pasion (1953) Bunuel's Brontë". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

- "Hihintayin Kita sa Langit (1991) - Manunuri ng Pelikulang Pilipino (MPP)". www.manunuri.com. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- "Classical Comics". Classical Comics. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- Whiteley, Sheila (2005). Too much too young: popular music, age and gender. Psychology Press. p. 9. ISBN 0-415-31029-6.

- "Wiplash". Whiplash (in Portuguese). Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- "EURINGER". JIMMY URINE. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- Steinman, Jim. "Jim Steinman on "It's All Coming Back to Me Now"". JimSteinman.com. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- Chira, Susan (13 December 2013). "Strange Moors: 'A True Novel' by Minae Mizuma". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- The West Indian.

- Douglas, Bob (19 February 2014). "The Eco-Gothic: Hilary Scharper's Perdita". Critics at Large.

- Grae, Tanya (2017). "Wuthering". Cordite Poetry Review. 57 (Confession). ISSN 1328-2107.

- Tepper, Anderson (5 September 1999). "Windward Heights". New York Times. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- Wolff, Rebecca. "Maryse Condé". BOMB Magazine. Archived from the original on 1 November 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

Bibliography

Editions

- Brontë, Emily (1976). Wuthering Heights. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-812511-9.

Introduction and notes by Ian Jack, Hilda Marsden, and Inga-Stina Ewbank.

Works of criticism

Books

- Allott, Miriam (1995). The Brontës: The Critical heritage. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-13461-3.

- Drabble, Margaret, ed. (1996) [1995]. "Charlotte Brontë". The Oxford Companion to English Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-866244-0.

- Doody, Margaret Anne (1997) [1996]. The True Story of the Novel. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0813524535.

- Hagan, Sandra; Wells, Juliette (2008). The Brontės in the World of the Arts. Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-5752-1.

- Moers, Ellen (1978) [1976]. Literary Women: The Great Writers. London: The Women’s Press. ISBN 978-0385074278.

- Scott, Walter (1834). "Essay on Romance". Prose Works of Sir Walter Scott. VI. R Cadell.

- Manning, Susan (1992), Introduction, Quentin Durward, by Scott, Walter, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0192826589

Journals

- Shumani, Gideon (March 1973). "The Unreliable Narrator in Wuthering Heights". Nineteenth-Century Fiction. 27 (4).

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wuthering Heights. |

- Wuthering Heights at the British Library

- Wuthering Heights: Landscape at YouTube – audio-video by the British Library

- Wuthering Heights is now in the public domain. Texts can be downloaded from or read online at numerous sites. A selection:

- Wuthering Heights at Project Gutenberg.

- Wuthering Heights at Standard Ebooks

- Wuthering Heights, overview and ebook (PDF).

- Wuthering Heights at GirleBooks free downloads in PDF, PDB and LIT formats.

- Reader's Guide to Wuthering Heights

- Wuthering Heights voted UK's favourite love story, Guardian

- Emily Brontë at Library of Congress Authorities, with 230 catalogue records – including 110 records of editions of Wuthering Heights