Korean name

A Korean name consists of a family name followed by a given name, as used by the Korean people in both South Korea and North Korea. In the Korean language, ireum or seongmyeong usually refers to the family name (seong) and given name (ireum in a narrow sense) together.

| Korean name | |

| Hangul | |

|---|---|

| Hanja | 이름 / 姓名 |

| Revised Romanization | ireum / seongmyeong |

| McCune–Reischauer | irŭm / sŏngmyŏng |

Traditional Korean family names typically consist of only one syllable. There is no middle name in the English language sense. Many Koreans have their given names made of a generational name syllable and an individually distinct syllable, though this practice is declining in the younger generations. The generational name syllable is shared by siblings in North Korea, and by all members of the same generation of an extended family in South Korea. Married men and women keep their full personal names, and children inherit the father's family name unless otherwise settled when registering the marriage.

The family names are subdivided into bon-gwan (clans), i.e. extended families which originate in the lineage system used in previous historical periods. Each clan is identified by a specific place, and traces its origin to a common patrilineal ancestor.

Early names based on the Korean language were recorded in the Three Kingdoms period (57 BCE – 668 CE), but with the growing adoption of the Chinese writing system, these were gradually replaced by names based on Chinese characters (hanja). During periods of Mongol influence, the ruling class supplemented their Korean names with Mongolian names.

Because of the many changes in Korean romanization practices over the years, modern Koreans, when using languages written in Latin script, romanize their names in various ways, most often approximating the pronunciation in English orthography. Some keep the original order of names, while others reverse the names to match the usual Western pattern.

According to the population and housing census of 2000 conducted by the South Korean government, there are a total of 286 surnames and 4,179 clans.[1]

Family names

| Hangul | Hanja | Revised | MR | Common spellings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 김 | 金 | Gim | Kim | Kim, Gim |

| 리 (N) 이 (S) |

李 | I | Ri (N) Yi (S) |

Lee, Rhee, Yi |

| 박 | 朴 | Bak | Pak | Park, Pak, Bak |

| 최 | 崔 | Choe | Ch'oe | Choi, Choe, Chue |

| 정 | 鄭 | Jeong | Chŏng | Chung, Jeong, Cheong, Jung |

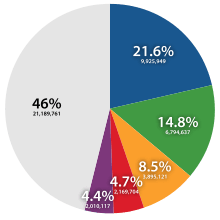

Fewer than 300 (approximately 280)[3] Korean family names were in use in 2000, and the three most common (Kim, Lee, and Park) account for nearly half of the population. For various reasons, there is a growth in the number of Korean surnames.[3][4] Each family name is divided into one or more clans (bon-gwan), identifying the clan's city of origin. For example, the most populous clan is Gimhae Kim; that is, the Kim clan from the city of Gimhae. Clans are further subdivided into various pa, or branches stemming from a more recent common ancestor, so that a full identification of a person's family name would be clan-surname-branch. For example, "Gyeongju Yissi" also romanized as "Gyeongju Leessi" (Gyeongju Lee clan, or Lee clan of Gyeongju) and "Yeonan-Yissi" (Lee clan of Yeonan) are, technically speaking, completely different surnames, even though both are, in most places, simply referred to as "Yi" or "Lee". This also means people from the same clan are considered to be of same blood, such that marriage of a man and a woman of same surname and bon-gwan is considered a strong taboo, regardless of how distant the actual lineages may be, even to the present day.

Traditionally, Korean women keep their family names after their marriage, but their children take the father's surname. In the premodern, patriarchal Korean society, people were extremely conscious of familial values and their own family identities. Korean women keep their surnames after marriage based on traditional reasoning that it is inherited from their parents and ancestors, and cannot be changed. According to traditions, each clan publishes a comprehensive genealogy (jokbo) every 30 years.[5]

Around a dozen two-syllable surnames are used, all of which rank after the 100 most common surnames. The five most common family names, which together make up over half of the Korean population, are used by over 20 million people in South Korea.[2]

After the 2015 census, it was revealed that foreign-origin family names were becoming more common in South Korea, due to naturalised citizens transcribing their surnames in hangul. Between 2000 and 2015, more than 4,800 new surnames were registered. During the census, a total of 5,582 distinct surnames were collected, 73% of which do not have corresponding hanja characters. It was also revealed that despite the surge in the number of surnames, the ratio of top 10 surnames had not changed. 44.6% of South Koreans are still named Kim, Lee or Park, while the rest of the top 10 are made up of Choi, Jeong, Kang, Jo, Yoon, Jang and Lim.[6]

Given names

Traditionally, given names are partly determined by generation names, a custom originating in China. One of the two characters in a given name is unique to the individual, while the other is shared by all people in a family generation. In both North and South Korea, generational names are usually no longer shared by cousins, but are still commonly shared by brothers and sisters.[7][8]

Given names are typically composed of hanja, or Chinese characters. In North Korea, the hanja are no longer used to write the names, but the meanings are still understood; thus, for example, the syllable cheol (철, 鐵) is used in boys' names and means "iron".

| Table of (Additional) Hanja for Personal Name Use | |

| Hangul | |

|---|---|

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Inmyeongyong chuga hanjapyo |

| McCune–Reischauer | Inmyŏngyong ch'uga hanchap'yo |

In South Korea, section 37 of the Family Registry Law requires that the hanja in personal names be taken from a restricted list.[9] Unapproved hanja must be represented by hangul in the family registry. In March 1991, the Supreme Court of South Korea published the Table of Hanja for Personal Name Use, which allowed a total of 2,854 hanja in new South Korean given names (as well as 61 alternative forms).[10] The list was expanded in 1994, 1997, 2001, 2005, 2007, 2008, 2010, 2013 and 2015. Thus, 8,142 hanja are now permitted in South Korean names (including the set of basic hanja), in addition to a small number of alternative forms.[11] The use of an official list is similar to Japan's use of the jinmeiyō kanji (although the characters do not entirely coincide).

While the traditional practice is still largely followed, since the late 1970s, some parents have given their children names that are native Korean words, usually of two syllables. Popular given names of this sort include Haneul (하늘; "Heaven" or "Sky"), Areum (아름; "Beauty"), Iseul (이슬; "Dew") and Seulgi (슬기; "Wisdom").[12] Between 2008 and 2015, the proportion of such names among South Korean newborns rose from 3.5% to 7.7%. The most popular such names in 2015 were Han-gyeol (한결; "Consistent, Unchanging") for boys and Sarang (사랑; "Love") for girls.[13] Despite this trend away from traditional practice, people's names are still recorded in both hangul and hanja (if available) on official documents, in family genealogies, and so on.

Originally, there was no legal limitation on the length of names in South Korea. As a result, some people registered extremely long given names composed of native Korean words, such as the 16-syllable Haneulbyeollimgureumhaennimbodasarangseureouri (하늘별님구름햇님보다사랑스러우리; roughly, "More beloved than the stars in the sky and the sun in the clouds"). However, beginning in 1993, new regulations required that the given name be five syllables or shorter.[14]

Usage

Forms of address

The usage of names is governed by strict norms in traditional Korean society. It is generally considered rude to address people by their given names in Korean culture. This is particularly the case when dealing with adults or one's elders.[15] It is acceptable to call someone by his or her given name if he or she is the same age as the speaker. However, it is considered rude to use someone's given name if that person's age is a year older than the speaker. This is often a source of pragmatic difficulty for learners of Korean as a foreign language, and for Korean learners of Western languages.

A variety of replacements are used for the actual name of the person. It is acceptable among adults of similar status to address the other by their full name, with the suffix ssi (氏, 씨) added. However, it is inappropriate to address someone by the surname alone, even with such a suffix.[16] Whenever the person has an official rank, it is typical to address him or her by the name of that rank (such as "Manager"), often with the honorific nim (님) added. In such cases, the full name of the person may be appended, although this can also imply the speaker is of higher status.[16]

Among children and close friends, it is common to use a person's birth name.

Traditional nicknames

Among the common people, who have suffered from high child mortality, children were often given amyeong (childhood name), to wish them long lives by avoiding notice from the messenger of death.[17] These sometimes-insulting nicknames are used sparingly for children today.[18]

After marriage, women usually lost their amyeong, and were called by a taekho, referring to their town of origin.[17]

In addition, teknonymy, or referring to parents by their children's names, is a common practice. It is most commonly used in referring to a mother by the name of her eldest child, as in "Cheolsu's mom" (철수 엄마). However, it can be extended to either parent and any child, depending upon the context.[19]

Gender

Korean given names' correlation to gender is complex, and by comparison to European languages less consistent.[20] Certain Sino-Korean syllables carry masculine connotations, others feminine, and others unisex. These connotations may vary depending on whether the character is used as the first or second character in the given name. A dollimja generational marker, once confined to male descendants but now sometimes used for women as well, may further complicate gender identification. Native Korean given names show similar variation.

A further complication in Korean text is that the singular pronoun used to identify individuals has no gender.[21] This means that automated translation often misidentifies or fails to identify individuals' gender in Korean text and thus presents stilted or incorrect English output. (Conversely, English source text is similarly missing information about social status and age critical to smooth Korean-language rendering.)[21]

Children traditionally take their father’s family name.[22] Under South Korean Civil Law effective 1 January 2008, though, children may be legally given the last name of either parent or even that of a step-parent.[23]

History

The use of names has evolved over time. The first recording of Korean names appeared as early as in the early Three Kingdoms period. The adoption of Chinese characters contributed to Korean names. A complex system, including courtesy names and pen names, as well as posthumous names and childhood names, arose out of Confucian tradition. The courtesy name system in particular arose from the Classic of Rites, a core text of the Confucian canon.[24]

During the Three Kingdoms period, native given names were sometimes composed of three syllables like Misaheun (미사흔) and Sadaham (사다함), which were later transcribed into hanja (未斯欣, 斯多含). The use of family names was limited to kings in the beginning, but gradually spread to aristocrats and eventually to most of the population.[25]

Some recorded family names are apparently native Korean words, such as toponyms. At that time, some characters of Korean names might have been read not by their Sino-Korean pronunciation, but by their native reading. For example, the native Korean name of Yeon Gaesomun (연개소문; 淵蓋蘇文), the first Grand Prime Minister of Goguryeo, can linguistically be reconstructed as "Eol Kasum" (/*älkasum/).[26] Early Silla names are also believed to represent Old Korean vocabulary; for example, Bak Hyeokgeose, the name of the founder of Silla, was pronounced something like "Bulgeonuri" (弗矩內), which can be translated as "bright world".[27]

In older traditions, if the name of a baby is not chosen by the third trimester, the responsibility of choosing the name fell to the oldest son of the family. Often, this was the preferred method as the name chosen was seen as good luck.

According to the chronicle Samguk Sagi, family names were bestowed by kings upon their supporters. For example, in 33 CE, King Yuri gave the six headmen of Saro (later Silla) the names Lee (이), Bae (배), Choi (최), Jeong (정), Son (손) and Seol (설). However, this account is not generally credited by modern historians, who hold that Confucian-style surnames as above were more likely to have come into general use in the fifth and subsequent centuries, as the Three Kingdoms increasingly adopted the Chinese model.[28]

Only a handful of figures from the Three Kingdoms period are recorded as having borne a courtesy name, such as Seol Chong. The custom only became widespread in the Goryeo period, as Confucianism took hold among the literati.[29] In 1055, Goryeo established a new law limiting access to the civil service examination to those with family names.[17]

For men of the aristocratic yangban class, a complex system of alternate names emerged by the Joseon period. On the other hand, commoners typically only had a first name.[17] Surnames were originally a privilege reserved for the yangban class, but members of the middle and common classes of Joseon society frequently paid to acquire a surname from a yangban and be included into a clan; this practice became rampant by the 18th century,[30] leading to a significant growth in the yangban class but conversely diluting and weakening its social dominance.[31] For instance, in the region of Daegu, the yangban who had comprised 9.2% of Daegu's demographics in 1690 rose to 18.7% in 1729, 37.5% in 1783, and 70.3% in 1858.[32] It was not until the Gabo Reform of 1894 that members of the outcast class were allowed to adopt a surname.[33] According to a census called the minjeokbu (民籍簿) completed in 1910, more than half of the Korean population did not have a surname at the time.[17]

For a brief period after the Mongol invasion of Korea during the Goryeo dynasty, Korean kings and aristocrats had both Mongolian and Sino-Korean names. The scions of the ruling class were sent to the Yuan court for schooling.[34] For example, King Gongmin had both the Mongolian name Bayan Temür (伯顏帖木兒) and the Sino-Korean name Wang Gi (王祺) (later renamed Wang Jeon (王顓)).[35]

During the period of Japanese colonial rule of Korea (1910–1945), Koreans were forced to adopt Japanese-language names.[36]

In 1939, as part of Governor-General Jiro Minami's policy of cultural assimilation (同化政策; dōka seisaku), Ordinance No. 20 (commonly called the "Name Order", or Sōshi-kaimei (創氏改名) in Japanese) was issued, and became law in April 1940.[37] Although the Japanese Governor-General officially prohibited compulsion, low-level officials effectively forced Koreans to adopt Japanese-style family and given names. By 1944, about 84% of the population had registered Japanese family names.[37]

Sōshi (Japanese) means the creation of a Japanese family name (shi, Korean ssi), distinct from a Korean family name or seong (Japanese sei). Japanese family names represent the families they belong to and can be changed by marriage and other procedures, while Korean family names represent paternal linkages and are unchangeable. Japanese policy dictated that Koreans either could register a completely new Japanese family name unrelated to their Korean surname, or have their Korean family name, in Japanese form, automatically become their Japanese name if no surname was submitted before the deadline.[38]

After the liberation of Korea from Japanese rule, the Name Restoration Order (조선 성명 복구령; 朝鮮姓名復舊令) was issued on October 23, 1946, by the United States military administration south of the 38th parallel north, enabling Koreans to restore their original Korean names if they wished.

Japanese conventions of creating given names, such as using "子" (Japanese ko and Korean ja) in feminine names, is seldom seen in present-day Korea, both North and South. In the North, a campaign to eradicate such Japanese-based names was launched in the 1970s.[7] In the South, and presumably in the North as well, these names are regarded as old and unsophisticated.

Romanization and pronunciation

In English-speaking nations, the three most common family names are often written and pronounced as "Kim" (김), "Lee" (South) or "Rhee" (North) (이, 리), and "Park" (박).

The initial sound in "Kim" shares features with both the English 'k' (in initial position, an aspirated voiceless velar stop) and "hard g" (an unaspirated voiced velar stop). When pronounced initially, Kim starts with an unaspirated voiceless velar stop sound; it is voiceless like /k/, but also unaspirated like /ɡ/. As aspiration is a distinctive feature in Korean but voicing is not, "Gim" is more likely to be understood correctly. However, "Kim" is used as romanized name in both North and South Korea.[39]

The family name "Lee" is romanized as 리 (ri) in North Korea and as 이 (i) in South Korea. In the former case, the initial sound is a liquid consonant. There is no distinction between the alveolar liquids /l/ and /r/, which is why "Lee" and "Rhee" are both common spellings. In South Korea, the pronunciation of the name is simply the English vowel sound for a "long e", as in 'see'. This pronunciation is also often spelled as "Yi"; the Northern pronunciation is commonly romanized "Ri".[40]

In Korean, the name that is usually romanized as "Park" actually has no 'r' sound. Its initial sound is an unaspirated voiced bilabial stop, like English 'b' at the beginning of words. The vowel is [a], similar to the 'a' in father and the 'a' in heart, so the name is also often transcribed "Pak, "Bak" and "Bahk." [41]

Many Korean names were romanized incorrectly from their actual pronunciation. For instance, Kim, Lee and Park are pronounced more closer to Ghim, Yi and Bahk in Korea. In order to correct this problem, South Korea's Ministry of Culture, Sports has developed the Revised Romanization of Korean to replace the older McCune–Reischauer system in the year 2000 and now the official spelling of these three names has been changed to Gim, I and Bak.

South Korea's Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism is encouraging those who "newly" register their passports to follow the Revised Romanization of Korean if possible, but it is not a mandatory and people are allowed to register their English name freely given that it's their first registration.[42]

In English

In English publications, usually Korean names are written in the original order, with the family name first and the given name last. This is the case in Western newspapers. Koreans living and working in Western countries have their names in the Western order, with the given name first and the family name last. The usual presentation of Korean names in English is similar to those of Chinese names and differs from those of Japanese names, which, in English publications, are usually written in a reversed order with the family name last.[43]

See also

Notes

- "2000 인구주택총조사 성씨 및 본관 집계결과". 통계청 (in Korean). Statistics Korea. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- Republic of Korea. National Statistical Office. Archived March 1, 2007, at the Wayback Machine The total population was 45,985,289. No comparable statistics are available from North Korea. The top 22 surnames are charted, and a rough extrapolation for both Koreas has been calculated "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-06-28. Retrieved 2006-08-22.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link).

- The Korean Drama & Movies Database, Everything you ever wanted to know about Korean surnames Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- U.S. Library of Congress, Traditional Family Life. Archived November 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Nahm, pg.33–34.

- "Foreign-origin family names on rise in South Korea". The Korea Herald. 2017-01-09. Retrieved 2017-01-10.

- NKChosun.com

- Harkrader, Lisa (2004). South Korea. Enslow Pub. Inc. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-7660-5181-2.

Many South Korean families today are relatively small, and may not include sons, so South Korean parents have begun to choose names for their sons that do not follow the traditional requirements of generation names.

- South Korea, Family Register Law

- National Academy of the Korean Language (1991) Archived March 19, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- '인명용(人名用)' 한자 5761→8142자로 대폭 확대. Chosun Ilbo (in Korean). 2014-10-20. Retrieved 2017-08-23.

- Jeon, Su-tae (2009-10-19). "사람 이름 짓기" [Making a name]. The Hankyoreh. Archived from the original on 2014-04-16. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

- 신생아 인기 이름 '민준·서연'…드라마 영향? [Popular names for newborns: Min-jun and Seo-yeon ... the effect of TV dramas?]. Seoul Broadcasting System. 9 May 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

신생아에게 한글 이름을 지어주는 경우는 2008년 전체의 3.5%에서 지난해에는 두 배가 넘는 7.7%에 달했습니다. 가장 많이 사용된 한글 이름은 남자는 '한결', 여자는 '사랑'이었습니다.

- "한국에서 가장 긴 이름은?" [What's the longest name in Korea?]. Hankyoreh. 18 January 2008. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- The Northern Forum (2006), p.29.

- Ri 2005, p.182.

- 이름. 다음 백과 (Daum Encyclopedia) (in Korean). Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- Naver Encyclopedia, Nickname (별명, 別名).

- Hwang (1991), p.9.

- Ask A Korean, It's Not Just That They All Look The Same Archived October 13, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, 4 August 2008

- Hee-Geun Yoon, Seng-Bae Park, Yong-Jin Han, Sang-Jo Lee, "Determining Gender of Korean Names with Context," alpit, pp.121-126, 2008 International Conference on Advanced Language Processing and Web Information Technology, 2008

- Nahm, Andrew C. (1988). Korea: Tradition and Transformation — A History of the Korean People. Elizabeth, NJ: Hollym International.

- Park, Chung-a, Children Can Adopt Mothers Surname Archived June 9, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The Korean Times, 3 June 2007

- Lee, Hong-jik (1983), p.1134.

- Do (1999), sec. 2.

- Chang, Sekyung, Phonetic and phonological study on the different transcriptions of the Same personal names, Seoul: Dongguk University (1990). (in Korean)

- Do (1999), sec. 3.

- Do (1999).

- Naver Encyclopedia, 자 [字]. Seol Chong's courtesy name, Chongji (총지) is reported in the Samguk Sagi, Yeoljeon 6, "Seol Chong".

- "Why so many Koreans are called Kim". The Economist. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- "(3) 사회 구조의 변동". 우리역사넷 (in Korean). National Institute of Korean History. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- "3) 양반 신분의 동향". 우리역사넷 (in Korean). National Institute of Korean History. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- 한국족보박물관 개관…‘족보 문화’의 메카 대전을 가다. 헤럴드경제 (in Korean). Herald Corporation. 26 May 2010. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- Lee (1984), p.156.

- Lee, Hong-jik (1983), p.117.

- U.S. Library of Congress, Korea Under Japanese Rule. Archived November 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Nahm (1996), p.223. See also Empas, "창씨개명".

- Empas, "창씨개명".

- Yonhap (2004), 484–536 and 793–800, passim.

- Yonhap (2004), pp. 561–608 and 807–810, passim.

- Yonhap (2004), pp.438–457.

- "로마자성명 표기 변경 허용 요건". Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2007. Retrieved 2019-05-21.

- Power, John. "Japanese names." (Archive) The Indexer. June 2008. Volume 26, Issue 2, p. C4-2-C4-8 (7 pages). ISSN 0019-4131. Accession number 502948569. Available on EBSCOHost.

Further reading

- Hwang, Shin Ja J. (1991). "Terms of Address In Korean and American Cultures" (pdf). Intercultural Communication Studies I:2. trinity.edu.

- Lee, Ki-baek (1984). A new history of Korea. Rev. ed., Tr. by Edward W. Wagner & Edward J. Shultz. Seoul: Ilchokak. ISBN 978-89-337-0204-8.

- Nahm, Andrew C. (1988). Korea: Tradition and Transformation — A History of the Korean People. Elizabeth, NJ: Hollym International. ISBN 978-0-930878-56-6.

- The Northern Forum (2006). "Protocol Manual". Anchorage, AK: northernforum.org. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

- U.S. Library of Congress (1990). "Korea Under Japanese Rule". In Andrea Matles Savada & William Shaw (ed.). South Korea: A Country Study. GPO for the Library of Congress. Retrieved 2006-08-10.

- U.S. Library of Congress (1990). "Traditional Family Life". In Andrea Matles Savada and William Shaw (ed.). South Korea: A Country Study. GPO for the Library of Congress. Retrieved 2006-08-10.

- Yonhap (2004). Korea Annual 2004. 41st annual ed. Seoul: Yonhap News Agency. ISBN 978-89-7433-070-5.

- Do, Su-hui (도수희) (1999). "Formation and Development of Korean Names (한국 성명의 생성 발달, Hanguk seongmyeong-ui saengseong baldal)" (PDF) (in Korean). New Korean Life (새국어생활). Retrieved 2018-05-28.

- Empas Encyclopedia (n.d.). "Changssi Gaemyeong (창씨개명, 創氏改名)" (in Korean). empas.com. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

- Lee, Hong-jik (이홍직), ed. (1983). "Ja, Courtesy Name (자)". Encyclopedia of Korean history (새國史事典, Sae guksa sajeon) (in Korean). Seoul: Kyohaksa. pp. 117, 1134. ISBN 978-89-09-00506-7.

- National Academy of the Korean Language (1991). "News from the National Academy of Korean Language (국립 국어 연구원 소식)" (in Korean). korean.go.kr. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

- National Institute of the Korean Language (국립 국어 연구원) (June 1991). "National Institute of the Korean Language news (Gungnip gugeo yeonguwon saesosik, 국어 국립 연구원 새소식)". New Korean Life (in Korean). korean.go.kr. Retrieved 2006-08-11.

- Naver Encyclopedia (n.d.). "Courtesy name (자, 字)" (in Korean). naver.com. Retrieved 2006-08-22.

- Naver Encyclopedia (n.d.). "Nickname (별명, 別名)" (in Korean). naver.com. Retrieved 2006-08-22.

- NKChosun (2000-11-19). "Name creation/'ja' disappearing from female names (이름짓기/ 여성 이름 '자'字 사라져)" (in Korean). nk.chosun.com. Retrieved 2006-08-13.

- Republic of Korea (n.d.). "Family Register Law 양계혈통 관련법률" (in Korean). root.re.kr. Archived from the original on 2007-02-11. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

- Republic of Korea (n.d.). "National Statistical Office" (in Korean). kosis.nso.go.kr. Archived from the original on 2006-09-07. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

- Ri, Ui-do (리의도) (2005). Proper Procedures for Korean Usage (올바른 우리말 사용법, Olbareun urimal sayongbeop) (in Korean). Seoul: Yedam. ISBN 978-89-5913-118-1.

External links

- Translate your name into Korean

- Korean surnames at Wiktionary

- Table of in 2001 added Hanja for Personal Name Use

- Choosing between Korean Hanja and Hangul Names

- Family Register Law, Act 6438, 호적법, 법률6438호, partially revised October 24, 2005. (in Korean)

- Examples of Koreans who used Japanese names: by Saga Women's Junior College (in Japanese)