Naming conventions in Ethiopia and Eritrea

The naming convention used in Eritrea and Ethiopia does not have family names and typically consists of an individual personal name and a separate patronymic. This is similar to Arabic, Icelandic, and Somali naming conventions. Traditionally for the Habesha peoples (Eritrean-Ethiopians), the lineage is traced paternally; legislation has been passed in Eritrea that allows for this to be done on the maternal side as well.

In this convention, children are given a name at birth, by which name they will be known.[1] To differentiate from others in the same generation with the same name, their father's first name and sometimes grandfather's first name is added. This may continue ad infinitum.[2] Outside Ethiopia, this is often mistaken for a surname or middle name but unlike European names, different generations do not have the same second or third names.[3]

In marriage, unlike in some Western societies, women do not change their maiden name, as the second name is not a surname.

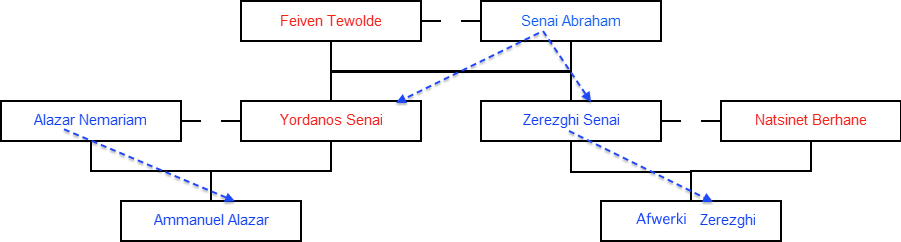

In the example above, the progenitors, Feiven and Senai, may be differentiated from others in their generation by their father's name. In this example, Feiven's and Senai's fathers' first names are Tewolde and Abraham respectively.

Feiven and Senai have a daughter and a son, each of whom is married and has a child. The first to have a child (a son) is their daughter, Yordanos Senai; she and her husband name the boy Ammanuel. The next sibling to have a child is Yordanos' brother, Zerezghi Senai; this child is also a son. As it is against custom to name a child after a living family member, his parents give him a different first name than his cousin: Afwerki. Ammanuel and Afwerki would each get their father's first name for their last.

In contemporary post-independence Eritrea, a person's legal name consists of their given name, followed by the given name of one of the parents (equivalent to a "middle name" in Western naming conventions) then the given name of grandparent (equivalent to a "last name" in Western naming conventions). In modern Ethiopia, a person's legal name includes both the father's and grandfather's given names, so that the father's given name becomes the child's "middle name" and the grandfather's given name becomes the child's "last name". In Ethiopian and traditionally in Eritrea, the naming conventions follow the father's line of descent while certain exemptions can be made in Eritrea in which the family may choose to use the mother's line of descent. Usually in both countries the grandparent's name or "last name" equivalent of the person is omitted in a similar way to how the middle name is omitted in Western naming conventions excluding important legal documents. Some peoples in the diaspora, use the above mentioned conventions but omit the father's given name/the person's "middle name" and proceed to the grandfather's name/the person's "last name" in accordance with Western conventions on middle names while retaining the portions of the patronymic conventions. On the other hand other peoples in the diaspora, will not give their children middle names but would adopt the grandfather's given name (the father's "middle name" or "last name" depending on the previous naming convention used) as the last name of the child.[4][3]

See also

References

- Tesfagiorgis G., Mussie (2010). Eritrea. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 236. ISBN 978-1-59884-231-9.

- Spencer, John H (2006). Ethiopia at bay : a personal account of the Haile Selassie years. Hollywood, CA: Tsehai. p. 26. ISBN 1-59907-000-6.

- Helebo, Fikru. "Ethiopian Naming System". Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- Tesfagiorgis, Mussie G. (October 29, 2010). Eritrea. ABC-CLIO. p. 236. ISBN 978-1598842319.