Organolithium reagent

Organolithium reagents are organometallic compounds that contain carbon – lithium bonds. They are important reagents in organic synthesis, and are frequently used to transfer the organic group or the lithium atom to the substrates in synthetic steps, through nucleophilic addition or simple deprotonation.[1] Organolithium reagents are used in industry as an initiator for anionic polymerization, which leads to the production of various elastomers. They have also been applied in asymmetric synthesis in the pharmaceutical industry.[2] Due to the large difference in electronegativity between the carbon atom and the lithium atom, the C-Li bond is highly ionic. Owing to the polar nature of the C-Li bond, organolithium reagents are good nucleophiles and strong bases. For laboratory organic synthesis, many organolithium reagents are commercially available in solution form. These reagents are highly reactive, and are sometimes pyrophoric.

History and development

Studies of organolithium reagents began in the 1930's and were pioneered by Karl Ziegler, Georg Wittig, and Henry Gilman. In comparison with Grignard (magnesium) reagents, organolithium reagents can often perform the same reactions with increased rates and higher yields, such as in the case of metalation.[3] Since then, organolithium reagents have overtaken Grignard reagents in common usage.[4]

Structure

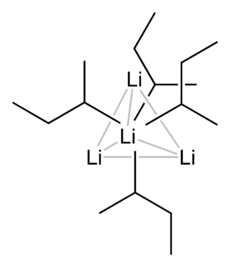

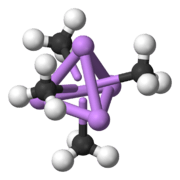

Although simple alkyllithium species are often represented as monomer RLi, they exist as aggregates (oligomers) or polymers.[5] The degree of aggregation depends on the organic substituent and the presence of other ligands.[6][7] These structures have been elucidated by a variety of methods, notably 6Li, 7Li, and 13C NMR spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction analysis.[1] Computational chemistry supports these assignments.[5]

Nature of carbon-lithium bond

The relative electronegativities of carbon and lithium suggest that the C-Li bond will be highly polar.[8][9][10] However, certain organolithium compounds possess properties such as solubility in nonpolar solvents that complicate the issue. [8] While most data suggest the C-Li bond to be essentially ionic, there has been debate as to whether a small covalent character exists in the C-Li bond.[9][10] One estimate puts the percentage of ionic character of alkyllithium compounds at 80 to 88%.[11]

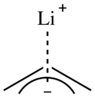

In allyl lithium compounds, the lithium cation coordinates to the face of the carbon π bond in an η3 fashion instead of a localized, carbanionic center, thus, allyllithiums are often less aggregated than alkyllithiums.[6][12] In aryllithium complexes, the lithium cation coordinates to a single carbanion center through a Li-C σ type bond.[6][13]

Solid state structure

Like other species consisting of polar subunits, organolithium species aggregate.[7][14] Formation of aggregates is influenced by electrostatic interactions, the coordination between lithium and surrounding solvent molecules or polar additives, and steric effects.[7]

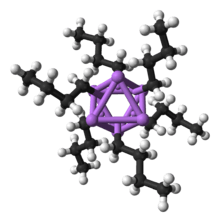

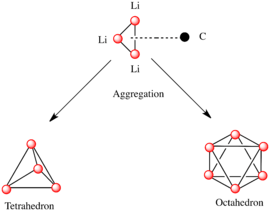

A basic building block toward constructing more complex structures is a carbanionic center interacting with a Li3 triangle in an η- 3 fashion.[5] In simple alkyllithium reagents, these triangles aggregate to form tetrahedron or octahedron structures. For example, methyllithium, ethyllithium and tert-butyllithium all exist in the tetramer [RLi]4. Methyllithium exists as tetramers in a cubane-type cluster in the solid state, with four lithium centers forming a tetrahedron. Each methanide in the tetramer in methyllithium can have agostic interaction with lithium cations in adjacent tetramers.[5][7] Ethyllithium and tert-butyllithium, on the other hand, do not exhibit this interaction, and are thus soluble in non-polar hydrocarbon solvents. Another class of alkyllithium adopts hexameric structures, such as n-butyllithium, isopropyllithium, and cyclohexanyllithium.[5]

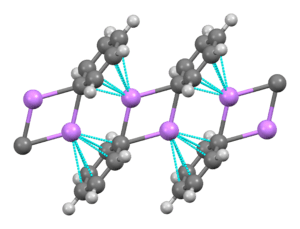

Common lithium amides, e.g. lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide and lithium diisopropylamide, are also subject to aggregation.[15] Lithium amides adopt polymeric-ladder type structures in non-coordinating solvent in the solid state, and they generally exist as dimers in ethereal solvents. In the presence of strongly donating ligands, tri- or tetrameric lithium centers are formed. [16] For example, LDA exists primarily as dimers in THF.[15] The structures of common lithium amides, such as lithium diisopropylamide (LDA) and lithium hexamethyldisilazide (LiHMDS) have been extensively studied by Collum and coworkers using NMR spectroscopy.[17] Another important class of reagents is silyllithiums, extensively used in the synthesis of organometallic complexes and polysilane dendrimers.[7][18] In the solid state, in contrast with alkyllithium reagents, most silyllithiums tend to form monomeric structures coordinated with solvent molecules such as THF, and only a few silyllithiums have been characterized as higher aggregates.[7] This difference can arise from the method of preparation of silyllithiums, the steric hindrance caused by the bulky alkyl substituents on silicon, and the less polarized nature of Si-Li bonds. The addition of strongly donating ligands, such as TMEDA and (-)-sparteine, can displace coordinating solvent molecules in silyllithiums.[7]

Solution structure

Relying solely on the structural information of organolithium aggregates obtained in the solid state from crystal structures has certain limits, as it is possible for organolithium reagents to adopt different structures in reaction solution environment.[6] Also, in some cases the crystal structure of an organolithium species can be difficult to isolate. Therefore, studying the structures of organolithium reagents, and the lithium-containing intermediates in solution form is extremely useful in understanding the reactivity of these reagents. [19] NMR spectroscopy has emerged as a powerful tool for the studies of organolithium aggregates in solution. For alkyllithium species, C-Li J coupling can often used to determine the number of lithium interacting with a carbanion center, and whether these interactions are static or dynamic.[6] Separate NMR signals can also differentiate the presence of multiple aggregates from a common monomeric unit.[20]

The structures of organolithium compounds are affected by the presence of Lewis bases such as tetrahydrofuran (THF), diethyl ether (Et2O), tetramethylethylene diamine (TMEDA) or hexamethylphosphoramide (HMPA).[5] Methyllithium is a special case, in which solvation with ether, or polar additive HMPA does not deaggregate the tetrameric structure in the solid state.[7] On the other hand, THF deaggregates hexameric butyl lithium: the tetramer is the main species, and ΔG for interconversion between tetramer and dimer is around 11 kcal/mol.[21] TMEDA can also chelate to the lithium cations in n-butyllithium and form solvated dimers such as [(TMEDA) LiBu-n)]2.[5][6] Phenyllithium has been shown to exist as a distorted tetramer in the crystallized ether solvate, and as a mixture of dimer and tetramer in ether solution.[6]

| Solvent | Structure | |

|---|---|---|

| methyllithium | THF | tetramer |

| methyllithium | ether/HMPA | tetramer |

| n-butyllithium | pentane | hexamer |

| n-butyllithium | ether | tetramer |

| n-butyllithium | THF | tetramer-dimer |

| sec-butyllithium | pentane | hexamer-tetramer |

| isopropyllithium | pentane | hexamer-tetramer |

| tert-butyllithium | pentane | tetramer |

| tert-butyllithium | THF | monomer |

| phenyllithium | ether | tetramer-dimer |

| phenyllithium | ether/HMPA | dimer |

Structure and reactivity

As the structures of organolithium reagents change according to their chemical environment, so do their reactivity and selectivity.[7][22] One question surrounding the structure-reactivity relationship is whether there exists a correlation between the degree of aggregation and the reactivity of organolithium reagents. It was originally proposed that lower aggregates such as monomers are more reactive in alkyllithiums.[23] However, reaction pathways in which dimer or other oligomers are the reactive species have also been discovered,[24] and for lithium amides such as LDA, dimer-based reactions are common.[25] A series of solution kinetics studies of LDA - mediated reactions suggest that lower aggregates of enolates do not necessarily lead to higher reactivity.[17]

Also, some Lewis bases increase reactivity of organolithium compounds.[26] [27] However, whether these additives function as strong chelating ligands, and how the observed increase in reactivity relates to structural changes in aggregates caused by these additives are not always clear.[26][27] For example, TMEDA increases rates and efficiencies in many reactions involving organolithium reagents.[7] Toward alkyllithium reagents, TMEDA functions as a donor ligand, reduces the degree of aggregation,[5] and increases the nucleophilicity of these species.[28] However, TMEDA does not always function as a donor ligand to lithium cation, especially in the presence of anionic oxygen and nitrogen centers. For example, it only weakly interacts with LDA and LiHMDS even in hydrocarbon solvents with no competing donor ligands.[29] In imine lithiation, while THF acts as a strong donating ligand to LiHMDS, the weakly coordinating TMEDA readily dissociates from LiHMDS, leading to the formation of LiHMDS dimers that is the more reactive species. Thus, in the case of LiHMDS, TMEDA does not increase reactivity by reducing aggregation state.[30] Also, as opposed to simple alkyllithium compounds, TMEDA does not deaggregate lithio-acetophenolate in THF solution.[6][31] The addition of HMPA to lithium amides such as LiHMDS and LDA often results in a mixture of dimer/monomer aggregates in THF. However, the ratio of dimer/monomer species does not change with increased concentration of HMPA, thus, the observed increase in reactivity is not the result of deaggregation. The mechanism of how these additives increase reactivity is still being researched.[22]

Reactivity and applications

The C-Li bond in organolithium reagents is highly polarized. As a result, the carbon attracts most of the electron density in the bond and resembles a carbanion. Thus, organolithium reagents are strongly basic and nucleophilic. Some of the most common applications of organolithium reagents in synthesis include their use as nucleophiles, strong bases for deprotonation, initiator for polymerization, and starting material for the preparation of other organometallic compounds.

As nucleophile

Carbolithiation reactions

As nucleophiles, organolithium reagents undergo carbolithiation reactions, whereby the carbon-lithium bond adds across a carbon-carbon double or triple bond, forming new organolithium species.[32] This reaction is the most widely employed reaction of organolithium compounds. Carbolithiation is key in anionic polymerization processes, and n-butyllithium is used as a catalyst to initiate the polymerization of styrene, butadiene, or isoprene or mixtures thereof.[33][34]

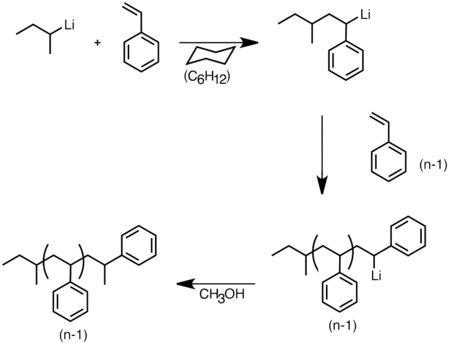

Anionic polymerization of styrene initiated by sec-butyllithium

Anionic polymerization of styrene initiated by sec-butyllithium

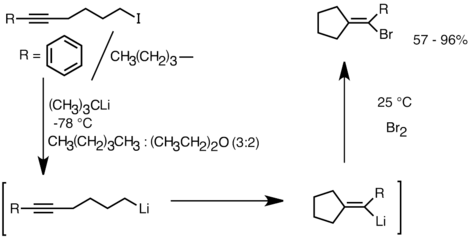

Another application that takes advantage of this reactivity is the formation of carbocyclic and heterocyclic coumpounds by intramolecular carbolithiation.[32] As a form of anionic cyclization, intramolecular carbolithiation reactions offer several advantages over radical cyclization. First, it is possible for the product cyclic organolithium species to react with electrophiles, whereas it is often difficult to trap a radical intermediate of the corresponding structure. Secondly, anionic cyclizations are often more regio- and stereospecific than radical cyclization, particularly in the case of 5-hexenyllithiums. Intramolecular carbolithiation allows addition of the alkyl-, vinyllithium to triple bonds and mono-alkyl substituted double bonds. Aryllithiums can also undergo addition if a 5-membered ring is formed. The limitations of intramolecular carbolithiation include difficulty of forming 3 or 4-membered rings, as the intermediate cyclic organolithium species often tend to undergo ring-openings.[32] Below is an example of intramolecular carbolithiation reaction. The lithium species derived from the lithium-halogen exchange cyclized to form the vinyllithium through 5-exo-trig ring closure. The vinyllithium species further reacts with electrophiles and produce functionalized cyclopentylidene compounds.[35]

A sample stereoselective intramolecular carbolithiation reaction

A sample stereoselective intramolecular carbolithiation reaction

Addition to carbonyl compounds

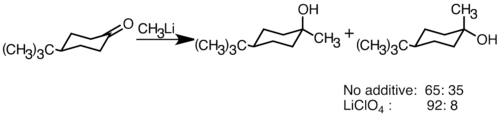

Nucleophilic organolithium reagents can add to electrophilic carbonyl double bonds to form carbon-carbon bonds. They can react with aldehydes and ketones to produce alcohols. The addition proceeds mainly via polar addition, in which the nucleophilic organolithium species attacks from the equatorial direction, and produces the axial alcohol.[36] Addition of lithium salts such as LiClO4 can improve the stereoselectivity of the reaction.[37]

LiClO4 increase selectivity of t BuLi

LiClO4 increase selectivity of t BuLi

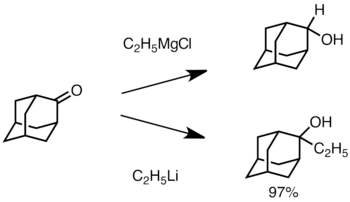

When the ketone is sterically hindered, using Grignard reagents often leads to reduction of the carbonyl group instead of addition.[36] However, alkyllithium reagents are less likely to reduce the ketone, and may be used to synthesize substituted alcohols.[38] Below is an example of ethyllithium addition to adamantone to produce tertiary alcohol.[39]

Li add to adamantone

Li add to adamantone

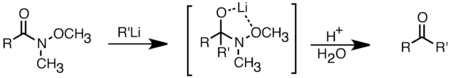

Organolithium reagents are also better than Grignard reagents in their ability to react with carboxylic acids to form ketones.[36] This reaction can be optimized by carefully controlling the amount of organolithium reagent addition, or using trimethylsilyl chloride to quench excess lithium reagent.[40] A more common way to synthesize ketones is through the addition of organolithium reagents to Weinreb amides (N-methoxy-N-methyl amides). This reaction provides ketones when the organolithium reagents is used in excess, due to chelation of the lithium ion between the N-methoxy oxygen and the carbonyl oxygen, which forms a tetrahedral intermediate that collapses upon acidic work up.[41]

Li add to weinreb

Li add to weinreb

Organolithium reagents can also react with carbon dioxide to form carboxylic acids.[42]

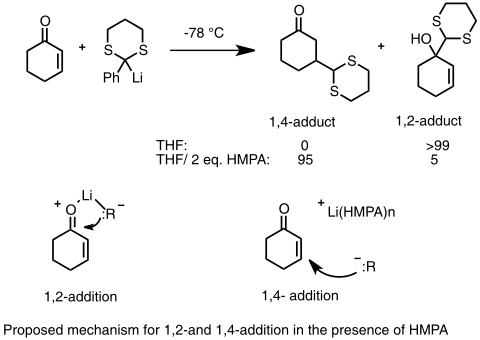

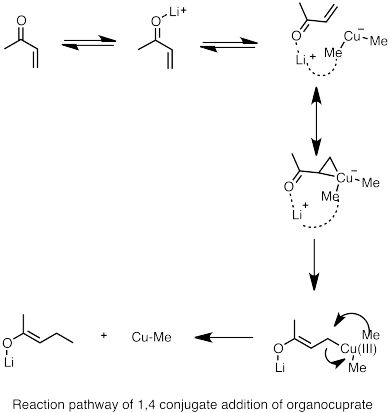

In the case of enone substrates, where two sites of nucleophilic addition are possible (1,2 addition to the carbonyl carbon or 1,4 conjugate addition to the β carbon), most highly reactive organolithium species favor the 1,2 addition, however, there are several ways to propel organolithium reagents to undergo conjugate addition. First, since the 1,4 adduct is the likely to be the more thermodynamically favorable species, conjugate addition can be achieved through equilibration (isomerization of the two product), especially when the lithium nucleophile is weak and 1,2 addition is reversible. Secondly, adding donor ligands to the reaction forms heteroatom-stabilized lithium species which favors 1,4 conjugate addition. In one example, addition of low-level of HMPA to the solvent favors the 1,4 addition. In the absence of donor ligand, lithium cation is closely coordinated to the oxygen atom, however, when the lithium cation is solvated by HMPA, the coordination between carbonyl oxygen and lithium ion is weakened. This method generally cannot be used to affect the regioselectivity of alkyl- and aryllithium reagents.[43][44]

1,4vs1,2 addition

1,4vs1,2 addition

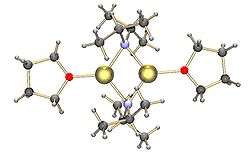

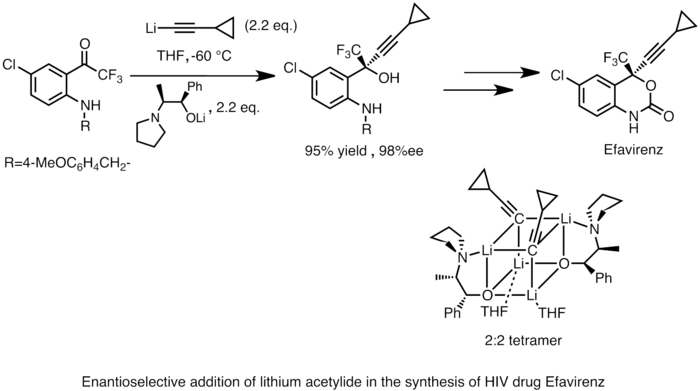

Organolithium reagents can also perform enantioselective nucleophilic addition to carbonyl and its derivatives, often in the presence of chiral ligands. This reactivity is widely applied in the industrial syntheses of pharmaceutical compounds. An example is the Merck and Dupont synthesis of Efavirenz, a potent HIV reverse transcriptase inhibitor. Lithium acetylide is added to a prochiral ketone to yield a chiral alcohol product. The structure of the active reaction intermediate was determined by NMR spectroscopy studies in the solution state and X-ray crystallography of the solid state to be a cubic 2:2 tetramer.[45]

Merck synthesis of Efavirenz

Merck synthesis of Efavirenz

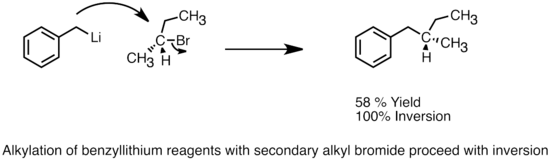

SN2 type reactions

Organolithium reagents can serve as nucleophiles and carry out SN2 type reactions with alkyl or allylic halides.[46] Although they are considered more reactive than Grignards reactions in alkylation, their use is still limited due to competing side reactions such as radical reactions or metal-halogen exchange. Most organolithium reagents used in a alkylations are more stabilized, less basic, and less aggregated, such as heteroatom stabilized, aryl- or allyllithium reagents.[6] HMPA has been shown to increase reaction rate and product yields, and the reactivity of aryllithium reagents is often enhanced by the addition of potassium alkoxides.[36] Organolithium reagents can also carry out nucleophilic attacks with epoxides to form alcohols.

SN2 inversion with benzyllithium

SN2 inversion with benzyllithium

As base

Organolithium reagents provide a wide range of basicity. tert-Butyllithium, with three weakly electron donating alkyl groups, is the strongest base commercially available (pKa = 53). As a result, the acidic protons on -OH, -NH and -SH are often protected in the presence of organolithium reagents. Some commonly used lithium bases are alkyllithium species such as n-butyllithium and lithium dialkylamides (LiNR2). Reagents with bulky R groups such as lithium diisopropylamide (LDA) and lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide (LiHMDS) are often sterically hindered for nucleophilic addition, and are thus more selective toward deprotonation. Lithium dialkylamides (LiNR2) are widely used in enolate formation and aldol reaction.[47] The reactivity and selectivity of these bases are also influenced by solvents and other counter ions.

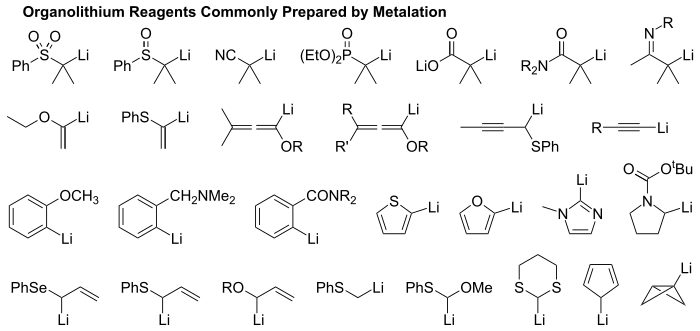

Metalation

Metalation with organolithium reagents, also known as lithiation or lithium-hydrogen exchange, is achieved when an organolithium reagent, most commonly an alkyllithium, abstracts a proton and forms a new organolithium species.

-

(1)

Common metalation reagents are the butyllithiums. tert-Butyllithium and sec-butyllithium are generally more reactive and have better selectivity than n-butyllithium, however, they are also more expensive and difficult to handle.[47] Metalation is a common way of preparing versatile organolithium reagents. The position of metalation is mostly controlled by the acidity of the C-H bond. Lithiation often occurs at a position α to electron withdrawing groups, since they are good at stabilizing the electron-density of the anion. Directing groups on aromatic compounds and heterocycles provide regioselective sites of metalation; directed ortho metalation is an important class of metalation reactions. Metalated sulfones, acyl groups and α-metalated amides are important intermediates in chemistry synthesis. Metalation of allyl ether with alkyllithium or LDA forms an anion α to the oxygen, and can proceed to 2,3-Wittig rearrangement. Addition of donor ligands such as TMEDA and HMPA can increase metalation rate and broaden substrate scope.[48] Chiral organolithium reagents can be accessed through asymmetric metalation.[49]

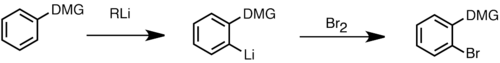

Directed ortho metalation

Directed ortho metalation

Directed ortho metalation is an important tool in the synthesis of regiospecific substituted aromatic compounds. This approach to lithiation and subsequent quenching of the intermediate lithium species with electrophile is often better than the electrophilic aromatic substitution due to its high regioselectivity. This reaction proceeds through deprotonation by organolithium reagents at the positions α to the direct metalation group (DMG) on the aromatic ring. The DMG is often a functional group containing a heteroatom that is Lewis basic, and can coordinate to the Lewis-acidic lithium cation. This generates a complex-induced proximity effect, which directs deprotonation at the α position to form an aryllithium species that can further react with electrophiles. Some of the most effective DMGs are amides, carbamates, sulfones and sulfonamides. They are strong electron-withdrawing groups that increase the acidity of alpha-protons on the aromatic ring. In the presence of two DMGs, metalation often occurs ortho to the stronger directing group, though mixed products are also observed. A number of heterocycles that contain acidic protons can also undergo ortho-metalation. However, for electron-poor heterocycles, lithium amide bases such as LDA are generally used, since alkyllithium has been observed to perform addition to the electron-poor heterocycles rather than deprotonation. In certain transition metal-arene complexes, such as ferrocene, the transition metal attracts electron-density from the arene, thus rendering the aromatic protons more acidic, and ready for ortho-metalation.[50]

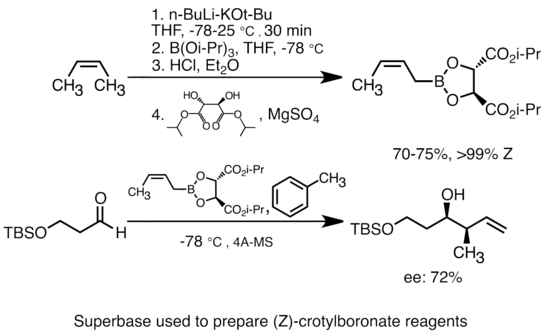

Superbases

Addition of potassium alkoxide to alkyllithium greatly increases the basicity of organolithium species.[51] The most common "superbase" can be formed by addition of KOtBu to butyllithium, often abbreviated as "LiCKOR" reagents. These "superbases" are highly reactive and often stereoselective reagents. In the example below, the LiCKOR base generates a stereospecific crotylboronate species through metalation and subsequent lithium-metalloid exchange.[52]

Superbase

Superbase

Asymmetric metalation

Enantioenriched organlithium species can be obtained through asymmetric metalation of prochiral substrates. Asymmetric induction requires the presence of a chiral ligand such as (-)-sparteine.[49] The enantiomeric ratio of the chiral lithium species is often influenced by the differences in rates of deprotonation. In the example below, treatment of N-Boc-N-benzylamine with n-butyllithium in the presence of (-)-sparteine affords one enantiomer of the product with high enantiomeric excess. Transmetalation with trimethyltinchloride affords the opposite enantiomer.[53]

-sparteine.png) Asymmetric synthesis with nBuLi and (-)-sparteine

Asymmetric synthesis with nBuLi and (-)-sparteine

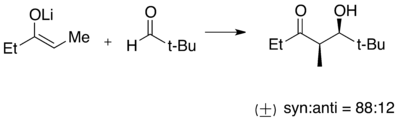

Enolate formation

Lithium enolates are formed through deprotonation of a C-H bond α to the carbonyl group by an organolithium species. Lithium enolates are widely used as nucleophiles in carbon-carbon bond formation reactions such as aldol condensation and alkylation. They are also an important intermediate in the formation of silyl enol ether.

Sample aldol reaction with lithium enolate

Sample aldol reaction with lithium enolate

Lithium enolate formation can be generalized as an acid-base reaction, in which the relatively acidic proton α to the carbonyl group (pK =20-28 in DMSO) reacts with organolithium base. Generally, strong, non-nucleophilic bases, especially lithium amides such LDA, LiHMDS and LiTMP are used. THF and DMSO are common solvents in lithium enolate reactions.[54]

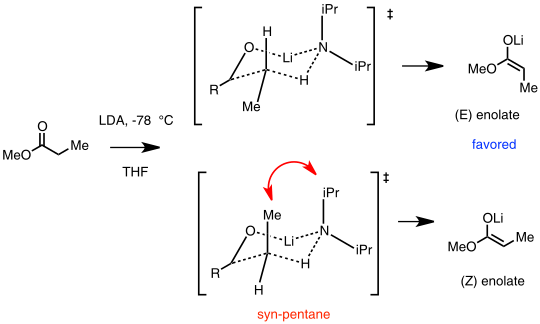

The stereochemistry and mechanism of enolate formation have gained much interest in the chemistry community. Many factors influence the outcome of enolate stereochemistry, such as steric effects, solvent, polar additives, and types of organolithium bases. Among the many models used to explain and predict the selectivity in stereochemistry of lithium enolates is the Ireland model.[55]

In this assumption, a monomeric LDA reacts with the carbonyl substrate and form a cyclic Zimmerman-Traxler type transition state. The (E)-enolate is favored due to an unfavorable syn-pentane interaction in the (Z)-enolate transition state.[54]

Ireland model for lithium enolate stereoselectivity. In this example, the (E) enolate is favored.

Ireland model for lithium enolate stereoselectivity. In this example, the (E) enolate is favored.

Addition of polar additives such as HMPA or DMPU favors the formation of (Z) enolates. The Ireland model argues that these donor ligands coordinate to the lithium cations, as a result, carbonyl oxygen and lithium interaction is reduced, and the transition state is not as tightly bound as a six-membered chair. The percentage of (Z) enolates also increases when lithium bases with bulkier side chains (such as LiHMDS) are used.[54] However, the mechanism of how these additives reverse stereoselectivity is still being debated.

There have been some challenges to the Ireland model, as it depicts the lithium species as a monomer in the transition state. In reality, a variety of lithium aggregates are often observed in solutions of lithium enolates, and depending on specific substrate, solvent and reaction conditions, it can be difficult to determine which aggregate is the actual reactive species in solution.[54]

Lithium-halogen exchange

Lithium-halogen exchange is a metathesis reaction between an organohalide and organolithium species. Gilman and Wittig independently discovered this method in the late 1930s.[56]

-

(2)

The mechanism of lithium-halogen exchange is still debated.[57] One possible pathway involves a nucleophilic mechanism that generates a reversible “ate-complex” intermediate. Farnham and Calabrese were able to isolate “ate-complex” lithium bis(pentafluorophenyl) iodinate complexed with TMEDA and obtain an X-ray crystal structure.[58] The "ate-complex" further reacts with electrophiles and provides pentafluorophenyl iodide and C6H5Li.[58] A number of kinetic studies also support a nucleophilic pathway in which the carbanion on the lithium species attacks the halogen atom on the aryl halide.[59] Another possible mechanism involves single electron transfer and the generation of radicals. In reactions of secondary and tertiary alkyllithium and alkyl halides, radical species were detected by EPR spectroscopy.[60] However, whether these radicals are reaction intermediates is not definitive.[57] The mechanistic studies of lithium-halogen exchange is also complicated by the formation of aggregates of organolithium species.

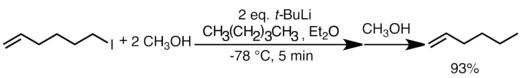

The rate of lithium halogen exchange is extremely fast. It is usually faster than nucleophilic addition and can sometimes exceed the rate of proton transfer. In the example below, the exchange between lithium and primary iodide is almost instantaneous, and outcompetes proton transfer from methanol to tert-butyllithium. The major alkene product is formed in over 90% yield.[61]

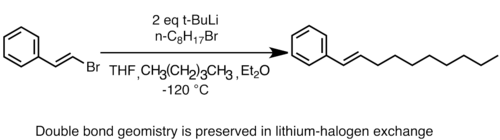

Lithium-halogen exchange is very useful in preparing new organolithium reagents. Exchange rates usually follow the trend I > Br > Cl. Alkyl- and arylfluoride are generally unreactive toward organolithium reagents. Lithium halogen exchange is kinetically controlled, and the rate of exchange is primarily influenced by the stabilities of the carbanion intermediates (sp > sp2 > sp3) of the organolithium reagents.[36][48] For example, the more basic tertiary organolithium reagents (usually n-butyllithium, sec-butyllithium or tert-butyllithium) are the most reactive, and will react with primary alkyl halide (usually bromide or iodide) to form the more stable organolithium species. Therefore, lithium halogen exchange is most frequently used to prepare vinyl-, aryl- and primary alkyllithium reagents. Lithium halogen exchange is also facilitated when alkoxy groups or heteroatoms are present to stabilize the carbanion, and this method is especially useful for the preparation of functionalized lithium reagents which cannot tolerate the harsher conditions required for reduction with lithium metal.[48] Substrates such as vinyl halides usually undergo lithium-halogen exchange with retention of the stereochemistry of the double bond.[62]

Retention of stereochem

Retention of stereochem

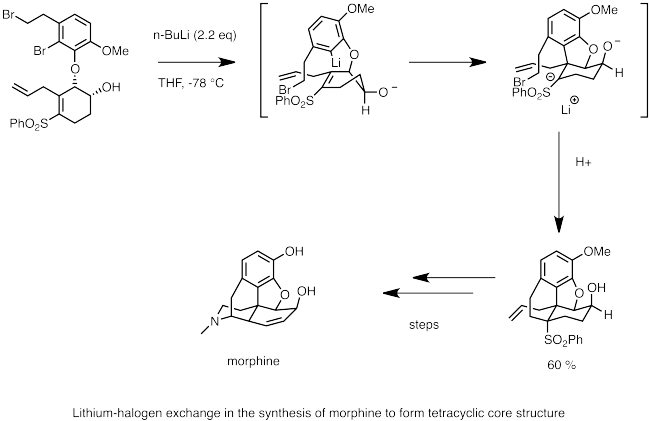

Below is an example of the use of lithium-halogen exchange in the synthesis of morphine. Here, n-butyllithium is used to perform lithium-halogen exchange with bromide. The nucleophilic carbanion center quickly undergoes carbolithiation to the double bond, generating an anion stabilized by the adjacent sulfone group. An intramolecular SN2 reaction by the anion forms the cyclic backbone of morphine.[63]

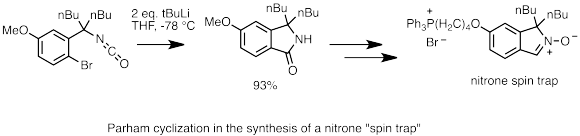

Lithium halogen exchange is a crucial part of Parham cyclization.[64] In this reaction, an aryl halide (usually iodide or bromide) exchanges with organolithium to form a lithiated arene species. If the arene bears a side chain with an electrophillic moiety, the carbanion attached to the lithium will perform intramolecular nucleophilic attack and cyclize. This reaction is a useful strategy for heterocycle formation.[65] In the example below, Parham cyclization was used to in the cyclization of an isocyanate to form isoindolinone, which was then converted to a nitrone. The nitrone species further reacts with radicals, and can be used as "spin traps" to study biological radical processes.[66]

Parham cyclization in MitoSpin

Parham cyclization in MitoSpin

Transmetalation

Organolithium reagents are often used to prepare other organometallic compounds by transmetalation. Organocopper, organotin, organosilicon, organoboron, organophosphorus, organocerium and organosulfur compounds are frequently prepared by reacting organolithium reagents with appropriate electrophiles.

-

(3)

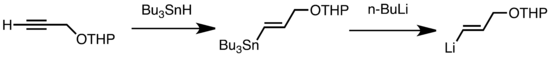

Common types of transmetalation include Li/Sn, Li/Hg, and Li/Te exchange, which are fast at low temperature.[47] The advantage of Li/Sn exchange is that the tri-alkylstannane precursors undergo few side reactions, as the resulting n-Bu3Sn byproducts are unreactive toward alkyllithium reagents.[47] In the following example, vinylstannane, obtained by hydrostannylation of a terminal alkyne, forms vinyllithium through transmetalation with n-BuLi.[67]

Li Sn exchange

Li Sn exchange

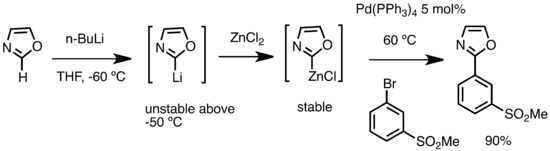

Organolithium can also be used in to prepare organozinc compounds through transmetalation with zinc salts.[68]

Organozinc reagents from alkyllithium

Organozinc reagents from alkyllithium

Lithium diorganocuprates can be formed by reacting alkyl lithium species with copper(I) halide. The resulting organocuprates are generally less reactive toward aldehydes and ketones than organolithium reagents or Grignard reagents.[69]

1,4 cuprate addition

1,4 cuprate addition

Preparation

Most simple alkyllithium reagents, and common lithium amides are commercially available in a variety of solvents and concentrations. Organolithium reagents can also be prepared in the laboratory. Below are some common methods for preparing organolithium reagents.

Reaction with lithium metal

Reduction of alkyl halide with metallic lithium can afford simple alkyl and aryl organolithium reagents.[36]

-

(4)

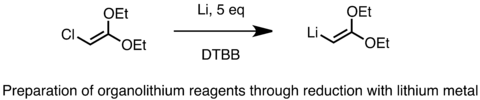

Industrial preparation of organolithium reagents is achieved using this method by treating the alkyl chloride with metal lithium containing 0.5-2% sodium. The conversion is highly exothermic. The sodium initiates the radical pathway and increases the rate.[70] The reduction proceeds via a radical pathway. Below is an example of the preparation of a functionalized lithium reagent using reduction with lithium metal.[71] Sometimes, lithium metal in the form of fine powders are used in the reaction with certain catalysts such as naphthalene or 4,4’-di-t-butylbiphenyl (DTBB). Another substrate that can be reduced with lithium metal to generate alkyllithium reagents is sulfides. Reduction of sulfides is useful in the formation of functionalized organolithium reagents such as alpha-lithio ethers, sulfides, and silanes.[72]

Reduction with Li metal

Reduction with Li metal

Metalation

A second method of preparing organolithium reagents is a metalation (lithium hydrogen exchange). The relative acidity of hydrogen atoms controls the position of lithiation.

This is the most common method for preparing alkynyllithium reagents, because the terminal hydrogen bound to the sp carbon is very acidic and easily deprotonated.[36] For aromatic compounds, the position of lithiation is also determined by the directing effect of substituent groups.[73] Some of the most effective directing substituent groups are alkoxy, amido, sulfoxide, sulfonyl. Metalation often occurs at the position ortho to these substituents. In heteroaromatic compounds, metalation usually occurs at the position ortho to the heteroatom.[36][73]

Lithium halogen exchange

See lithium-halogen exchange (under Reactivity and applications)

A third method to prepare organolithium reagents is through lithium halogen exchange.

tert-butyllithium or n-butyllithium are the most commonly used reagents for generating new organolithium species through lithium halogen exchange. Lithium-halogen exchange is mostly used to convert aryl and alkenyl iodides and bromides with sp2 carbons to the corresponding organolithium compounds. The reaction is extremely fast, and often proceed at -60 to -120 °C.[48]

Transmetalation

The fourth method to prepare organolithium reagents is through transmetalation. This method can be used for preparing vinyllithium.

Shapiro reaction

In the Shapiro reaction, two equivalents of strong alkyllithium base react with p-tosylhydrazone compounds to produce the vinyllithium, or upon quenching, the olefin product.

Handling

Organolithium compounds are highly reactive species and require specialized handling techniques. They are often corrosive, flammable, and sometimes pyrophoric (spontaneous ignition when exposed to oxygen or moisture).[74] Alkyllithium reagents can also undergo thermal decomposition to form the corresponding alkyl species and lithium hydride.[75] Organolithium reagents are typically stored below 10 °C. Reactions are conducted using air-free techniques.[74] The concentration of alkyllithium reagents is often determined by titration.[76][77][78]

Organolithium reagents react, often slowly, with ethers, which nonetheless are often used as solvents.[79]

| Solvent | Temp | n-BuLi | s-BuLi | t-BuLi | MeLi | CH2=C(OEt)-Li | CH2=C(SiMe3)-Li |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| THF | -40 °C | 338 min | |||||

| THF | -20 °C | 42 min | |||||

| THF | 0 °C | 17 h | |||||

| THF | 20 °C | 107 min | >15 h | 17 h | |||

| THF | 35 °C | 10 min | |||||

| THF/TMEDA | -20 °C | 55 h | |||||

| THF/TMEDA | 0 °C | 340 min | |||||

| THF/TMEDA | 20 °C | 40 min | |||||

| Ether | -20 °C | 480 min | |||||

| Ether | 0 °C | 61 min | |||||

| Ether | 20 °C | 153 h | <30 min | 17 d | |||

| Ether | 35 °C | 31 h | |||||

| Ether/TMEDA | 20 °C | 603 min | |||||

| DME | -70 °C | 120 min | 11 min | ||||

| DME | -20 °C | 110 min | 2 min | ≪2 min | |||

| DME | 0 °C | 6 min |

See also

References

- Zabicky, Jacob (2009). "Analytical aspects of organolithium compounds". PATAI'S Chemistry of Functional Groups. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/9780470682531.pat0304. ISBN 9780470682531.

- Wu, G.; Huang, M. (2006). "Organolithium Reagents in Pharmaceutical Asymmetric Processes". Chem. Rev. 106 (7): 2596–2616. doi:10.1021/cr040694k. PMID 16836294.

- Eisch, John J. (2002). "Henry Gilman: American Pioneer in the Rise of Organometallic Chemistry in Modern Science and Technology†". Organometallics. 21 (25): 5439–5463. doi:10.1021/om0109408. ISSN 0276-7333.

- Rappoport, Z.; Marek, I., eds. (2004). The Chemistry of Organolithium Compounds (2 parts). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-470-84339-0.

- Stey, Thomas; Stalke, Dietmar (2009). "Lead structures in lithium organic chemistry". PATAI'S Chemistry of Functional Groups. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/9780470682531.pat0298. ISBN 9780470682531.

- Reich, Hans J. (2013). "Role of Organolithium Aggregates and Mixed Aggregates in Organolithium Mechanisms". Chemical Reviews. 113 (9): 7130–7178. doi:10.1021/cr400187u. PMID 23941648.

- Strohmann, C; et al. (2009). "Structure Formation Principles and Reactivity of Organolithium Compounds" (PDF). Chem. Eur. J. 15 (14): 3320–3334. doi:10.1002/chem.200900041. PMID 19260001.

- Jemmis, E.D.; Gopakumar, G. (2009). "Theoretical studies in organolithium chemistry". PATAI'S Chemistry of Functional Groups. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/9780470682531.pat0297. ISBN 9780470682531.

- Streiwieser, A. (2009). "Perspectives on Computational Organic Chemistry". J. Org. Chem. 74 (12): 4433–4446. doi:10.1021/jo900497s. PMC 2728082. PMID 19518150.

- Bickelhaupt, F. M.; et al. (2006). "Covalency in Highly Polar Bonds. Structure and Bonding of Methylalkalimetal Oligomers (CH3M)n (M = Li−Rb; n = 1, 4)". J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2 (4): 965–980. doi:10.1021/ct050333s. PMID 26633056.

- Weiss, Erwin (November 1993). "Structures of Organo Alkali Metal Complexes and Related Compounds". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 32 (11): 1501–1523. doi:10.1002/anie.199315013. ISSN 0570-0833.

- Fraenkel, G.; Qiu, Fayang (1996). "Observation of a Partially Delocalized Allylic Lithium and the Dynamics of Its 1,3 Lithium Sigmatropic Shift". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118 (24): 5828–5829. doi:10.1021/ja960440j.

- Fraenkel. G; et al. (1995). "The carbon-lithium bond in monomeric arllithium: Dynamics of exchange, relaxation and rotation". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117 (23): 6300–6307. doi:10.1021/ja00128a020.

- Power, P.P; Hope H. (1983). "Isolation and crystal structures of the halide-free and halide-rich phenyllithium etherate complexes [(PhLi.Et2O)4] and [(PhLi.Et2O)3.LiBr]". JACS. 105 (16): 5320–5324. doi:10.1021/ja00354a022.

- Williard, P. G.; Salvino, J. M. (1993). "Synthesis, isolation, and structure of an LDA-THF complex". Journal of Organic Chemistry. 58 (1): 1–3. doi:10.1021/jo00053a001.

- Hilmersson, Goran; Granander, Johan (2009). "Structure and dynamics of chiral lithium amides". PATAI'S Chemistry of Functional Groups. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/9780470682531.pat0342. ISBN 9780470682531.

- Collum, D.B.; et al. (2007). "Lithium Diisopropylamide: Solution Kinetics and Implications for Organic Synthesis". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49 (17): 3002–3017. doi:10.1002/anie.200603038. PMID 17387670.

- Sekiguchi, Akira.; et al. (2000). "Lithiosilanes and their application to the synthesis of polysilane dendrimers". Coord. Chem. Rev. 210: 11–45. doi:10.1016/S0010-8545(00)00315-5.

- Collum, D. B.; et al. (2008). "Solution Structures of Lithium Enolates, Phenolates, Carboxylates, and Alkoxides in the Presence of N,N,N′,N′-Tetramethylethylenediamine: A Prevalence of Cyclic Dimers". J. Org. Chem. 73 (19): 7743–7747. doi:10.1021/jo801532d. PMC 2636848. PMID 18781812.

- Reich, H. J.; et al. (1998). "Aggregation and reactivity of phenyllithium solutions". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120 (29): 7201–7210. doi:10.1021/ja980684z.

- McGarrity, J. F.; Ogle, C.A. (1985). "High-field proton NMR study of the aggregation and complexation of n-butyllithium in tetrahydrofuran". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 107 (7): 1805–1810. doi:10.1021/ja00293a001.

- Reich, H. J. (2012). "What's going on with these lithium reagents". J. Org. Chem. 77 (13): 5471–5491. doi:10.1021/jo3005155. PMID 22594379.

- Wardell, J.L. (1982). "Chapter 2". In Wilinson, G.; Stone, F. G. A.; Abel, E. W. (eds.). Comprehensive Organometallic Chemistry, Vol. 1 (1st ed.). New York: Pergamon. ISBN 978-0080406084.

- Strohmann, C.; Gessner, V.H. (2008). "Crystal Structures of n-BuLi Adducts with (R,R)-TMCDA and the Consequences for the Deprotonation of Benzene". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130 (35): 11719–11725. doi:10.1021/ja8017187. PMID 18686951.

- Collum, D. B.; et al. (2007). "Lithium Diisopropylamide: Solution Kinetics and Implications for Organic Synthesis". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46 (17): 3002–3017. doi:10.1002/anie.200603038. PMID 17387670.

- Chalk, A.J; Hoogeboom, T.J (1968). "Ring metalation of toluene by butyllithium in the presence of N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethylenediamine". J. Organomet. Chem. 11: 615–618. doi:10.1016/0022-328x(68)80091-9.

- Reich, H.J; Green, D.P (1989). "Spectroscopic and Reactivity Studies of Lithium Reagent - HMPA Complexes". JACS. 111 (23): 8729–8731. doi:10.1021/ja00205a030.

- Williard, P.G; Nichols, M.A (1993). "Solid-state structures of n-butyllithium-TMEDA, -THF, and -DME complexes". JACS. 115 (4): 1568–1572. doi:10.1021/ja00057a050.

- Collum, D.B. (1992). "Is N,N,N,N-Tetramethylethylenediamine a Good Ligand for Lithium?". Acc. Chem. Res. 25 (10): 448–454. doi:10.1021/ar00022a003.

- Bernstein, M.P.; Collum, D.B. (1993). "Solvent- and substrate-dependent rates of imine metalations by lithium diisopropylamide: understanding the mechanisms underlying krel". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115 (18): 8008–8010. doi:10.1021/ja00071a011.

- Seebach, D (1988). "Structure and Reactivity of Lithium Enolates. From Pinacolone to Selective C-Alkylations of Peptides. Difficulties and Opportunities Afforded by Complex Structures" (PDF). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 27 (12): 1624–1654. doi:10.1002/anie.198816241.

- Fananas, Francisco; Sanz, Roberto (2009). "Intramolecular carbolithiation reactions". PATAI'S Chemistry of Functional Groups. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/9780470682531.pat0341. ISBN 9780470682531.

- Heinz-Dieter Brandt, Wolfgang Nentwig1, Nicola Rooney, Ronald T. LaFlair, Ute U. Wolf, John Duffy, Judit E. Puskas, Gabor Kaszas, Mark Drewitt, Stephan Glander "Rubber, 5. Solution Rubbers" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2011, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.o23_o02

- Baskara, D.; Muller, A.H. (2010). "Anionic Vinyl Polymerization". Controlled and living polymerizations: From mechanisms to applications. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. doi:10.1002/9783527629091.ch1. ISBN 9783527629091.

- Bailey, W.F.; et al. (1989). "Preparation and facile cyclization of 5-alkyn-1-yllithiums". Tetrahedron Lett. 30 (30): 3901–3904. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)99279-7.

- Carey, Francis A. (2007). "Organometallic compounds of Group I and II metals". Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reaction and Synthesis Pt. B (Kindle ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-44899-2.

- Ashby, E.C.; Noding, S.R. (1979). "The effects of added salts on the stereoselectivity and rate of organometallic compound addition to ketones". J. Org. Chem. 44 (24): 4371–4377. doi:10.1021/jo01338a026.

- Yamataka, Hiroshi (2009). "Addition of organolithium reagents to double bonds". PATAI'S Chemistry of Functional Groups. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/9780470682531.pat0310. ISBN 9780470682531.

- Landa, S.; et al. (1967). "Über adamantan und dessen derivate IX. In 2-stellung substituierte derivate". Collection of Czechoslovak Chemical Communications. 72 (2): 570–575. doi:10.1135/cccc19670570.

- Rubottom, G.M.; Kim, C (1983). "Preparation of methyl ketones by the sequential treatment of carboxylic acids with methyllithium and chlorotrimethylsilane". J. Org. Chem. 48 (9): 1550–1552. doi:10.1021/jo00157a038.

- Zadel, G.; Breitmaier, E. (1992). "A One-Pot Synthesis of Ketones and Aldehydes from Carbon Dioxide and Organolithium Compounds". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 31 (8): 1035–1036. doi:10.1002/anie.199210351.

- Ronald, R.C. (1975). "Methoxymethyl ethers. An activating group for rapid and regioselective metalation". Tetrahedron Lett. 16 (46): 3973–3974. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)91212-7.

- Hunt, D.A. (1989). "Michael addition of organolithium compounds. A Review". Org. Prep. Proc. Int. 21 (6): 705–749. doi:10.1080/00304948909356219.

- Reich, H. J.; Sikorski, W. H. (1999). "Regioselectivity of Addition of Organolithium Reagents to Enones: The Role of HMPA". J. Org. Chem. 64 (1): 14–15. doi:10.1021/jo981765g. PMID 11674078.

- Collum, D.B.; et al. (2001). "NMR Spectroscopic Investigations of Mixed Aggregates Underlying Highly Enantioselective 1,2-Additions of Lithium Cyclopropylacetylide to Quinazolinones". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123 (37): 9135–9143. doi:10.1021/ja0105616. PMID 11552822.

- Sommmer, L.H.; Korte, W. D. (1970). "Stereospecific coupling reactions between organolithium reagents and secondary halides". J. Org. Chem. 35: 22–25. doi:10.1021/jo00826a006.

- Organolithium Reagents Reich, H.J. 2002 http://www.chem.wisc.edu/areas/reich/handouts/lireagents/orgli-primer.pdf

- The Preparation of Organolithium Reagents and Intermediates Leroux.F., Schlosser. M., Zohar. E., Marek. I., Wiley, New York. 2004. ISBN 978-0-470-84339-0

- Hoppe, Dieter; Christoph, Guido (2009). "Asymmetric deprotonation with alkyllithium– (−)-sparteine". PATAI'S Chemistry of Functional Groups. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/9780470682531.pat0313. ISBN 9780470682531.

- Clayden, Jonathan (2009). "Directed metallization of aromatic compounds". PATAI'S Chemistry of Functional Groups. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/9780470682531.pat0306. ISBN 9780470682531.

- Schlosser, M (1988). "Superbases for organic synthesis". Pure Appl. Chem. 60 (11): 1627–1634. doi:10.1351/pac198860111627.

- Roush, W.R.; et al. (1988). "Enantioselective synthesis using diisopropyl tartrate modified (E)- and (Z)-crotylboronates: Reactions with achiral aldehydes". Tetrahedron Lett. 29 (44): 5579–5582. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)80816-3.

- Park, Y.S.; et al. (1996). "(−)-Sparteine-Mediated α-Lithiation of N-Boc-N-(p-methoxyphenyl)benzylamine: Enantioselective Syntheses of (S) and (R) Mono- and Disubstituted N-Boc-benzylamines". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118 (15): 3757–3758. doi:10.1021/ja9538804.

- Valnot, Jean-Yves; Maddaluno, Jacques (2009). "Aspects of the synthesis, structure and reactivity of lithium enolates". PATAI'S Chemistry of Functional Groups. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/9780470682531.pat0345. ISBN 9780470682531.

- Ireland. R. E.; et al. (1976). "The ester enolate Claisen rearrangement. Stereochemical control through stereoselective enolate formation". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 98 (10): 2868–2877. doi:10.1021/ja00426a033.

- Gilman, Henry; Langham, Wright; Jacoby, Arthur L. (1939). "Metalation as a Side Reaction in the Preparation of Organolithium Compounds". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 61 (1): 106–109. doi:10.1021/ja01870a036. ISSN 0002-7863.

- Bailey, W. F.; Patricia, J. F. (1988). "The mechanism of the lithium - halogen Interchange reaction : a review of the literature". J. Organomet. Chem. 352 (1–2): 1–46. doi:10.1016/0022-328X(88)83017-1.

- Farnham, W. B.; Calabrese, J. C. (1986). "Novel hypervalent (10-I-2) iodine structures". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 108 (9): 2449–2451. doi:10.1021/ja00269a055. PMID 22175602.

- Rogers, H. R.; Houk, J. (1982). "Preliminary studies of the mechanism of metal-halogen exchange. The kinetics of reaction of n-butyllithium with substituted bromobenzenes in hexane solution". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 104 (2): 522–525. doi:10.1021/ja00366a024.

- Fischer, H. (1969). "Electron spin resonance of transient alkyl radicals during alkyllithium-alkyl halide reactions". J. Phys. Chem. 73 (11): 3834–3838. doi:10.1021/j100845a044.

- Bailey, W.F.; et al. (1986). "Metal—halogen interchange between t-butyllithium and 1-iodo-5-hexenes provides no evidence for single-electron transfer". Tetrahedron Lett. 27 (17): 1861–1864. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)84395-6.

- Seebach, D; Neumann H. (1976). "Stereospecific preparation of terminal vinyllithium derivatives by Br/Li-exchange with t-butyllithium". Tetrahedron Lett. 17 (52): 4839–4842. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)78926-x.

- Toth, J. E.; Hamann, P.R.; Fuchs, P.L. (1988). "Studies culminating in the total synthesis of (dl)-morphine". J. Org. Chem. 53 (20): 4694–4708. doi:10.1021/jo00255a008.

- Parham, W.P.; Bradsher, C.K. (1982). "Aromatic organolithium reagents bearing electrophilic groups. Preparation by halogen-lithium exchange". Acc. Chem. Res. 15 (10): 300–305. doi:10.1021/ar00082a001.

- Sotomayor, N.; Lete, E. (2003). "Aryl and Heteroaryllithium Compounds by Metal - Halogen Exchange. Synthesis of Carbocyclic and Heterocyclic Systems". Curr. Org. Chem. 7 (3): 275–300. doi:10.2174/1385272033372987.

- Quin, C.; et al. (2009). "Synthesis of a mitochondria-targeted spin trap using a novel Parham-type cyclization". Tetrahedron. 65 (39): 8154–8160. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2009.07.081. PMC 2767131. PMID 19888470.

- Corey, E.J.; Wollenberg, R.H. (1975). "Useful new organometallic reagents for the synthesis of allylic alcohols by nucleophilic vinylation". J. Org. Chem. 40 (15): 2265–2266. doi:10.1021/jo00903a037.

- Reeder, M.R.; et al. (2003). "An Improved Method for the Palladium Cross-Coupling Reaction of Oxazol-2-ylzinc Derivatives with Aryl Bromides". Org. Process Res. Dev. 7 (5): 696–699. doi:10.1021/op034059c.

- Nakamura, E.; et al. (1997). "Reaction Pathway of the Conjugate Addition of Lithium Organocuprate Clusters to Acrolein". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119 (21): 4900–4910. doi:10.1021/ja964209h.

- "Organometallics in Organic Synthesis", Schlosser, M., Ed, Wiley: New York, 1994. ISBN 0-471-93637-5

- Si-Fodil, M.; et al. (1998). "Obtention of 2,2-(diethoxy) vinyl lithium and 2-methyl-4-ethoxy butadienyl lithium by arene-catalysed lithiation of the corresponding chloro derivatives. Synthetic applications". Tetrahedron Lett. 39 (49): 8975–8978. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(98)02031-0.

- Cohen, T; Bhupathy. M (1989). "Organoalkali compounds by radical anion induced reductive metalation of phenyl thioethers". Acc. Chem. Res. 22 (4): 152–161. doi:10.1021/ar00160a006.

- Snieckus, V (1990). "Directed ortho metalation. Tertiary amide and O-carbamate directors in synthetic strategies for polysubstituted aromatics". Chem. Rev. 90 (6): 879–933. doi:10.1021/cr00104a001.

- Schwindeman, James A.; Woltermann, Chris J.; Letchford, Robert J. (2002). "Safe handling of organolithium compounds in the laboratory". Chemical Health and Safety. 9 (3): 6–11. doi:10.1016/S1074-9098(02)00295-2. ISSN 1074-9098.

- Gellert, H; Ziegler, K. (1950). "Organoalkali compounds. XVI. The thermal stability of lithium alkyls". Liebigs Ann. Chem. 567: 179–185. doi:10.1002/jlac.19505670110.

- Juaristi, E.; Martínez-Richa, A.; García-Rivera, A.; Cruz-Sánchez, J. S. (1983). "Use of 4-Biphenylmethanol, 4-Biphenylacetic Acid and 4-Biphenylcarboxylic Acid/Triphenylmethane as Indicators in the Titration of Lithium Alkyls. Study of the Dianion of 4-Biphenylmethanol". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 48 (15): 2603–2606. doi:10.1021/jo00163a038.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Titrating Soluble RM, R2NM and ROM Reagents" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- "Methods for Standardizing Alkyllithium Reagents (literature through 2006)" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- Stanetty, P.; Koller, H.; Mihovilovic, M. (1992). "Directed Ortho-Lithiation of Phenylcarbamic Acid 1,l-Dimethylethyl Ester (N-Boc-aniline). Revision and Improvements". J. Org. Chem. 57 (25): 6833–6837. doi:10.1021/jo00051a030.