Aliger gigas

Aliger gigas, originally known as Strombus gigas or more recently as Lobatus gigas, commonly known as the queen conch, is a species of large edible sea snail, a marine gastropod mollusc in the family of true conches, the Strombidae. This species is one of the largest molluscs native to the Caribbean Sea, and tropical northwestern Atlantic, from Bermuda to Brazil, reaching up to 35.2 centimetres (13.9 in) in shell length. A. gigas is closely related to the goliath conch, Lobatus goliath, a species endemic to Brazil, as well as the rooster conch, Lobatus gallus.

| Aliger gigas | |

|---|---|

| |

| A live subadult individual of Aliger gigas, in situ surrounded by turtle grass | |

| |

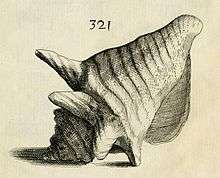

| A dorsal view of an adult individual of A. gigas from Chenu, 1844 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Gastropoda |

| Clade: | Caenogastropoda |

| Clade: | Hypsogastropoda |

| Order: | Littorinimorpha |

| Family: | Strombidae |

| Genus: | Aliger |

| Species: | A. gigas |

| Binomial name | |

| Aliger gigas | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

Strombus gigas Linnaeus, 1758[2] | |

The queen conch is herbivorous. It feeds by browsing for plant and algal material growing in the seagrass beds, and scavenging for decaying plant matter. These large sea snails typically reside in seagrass beds, which are sandy plains covered in swaying sea grass and associated with coral reefs, although the exact habitat of this species varies according to developmental age. The adult animal has a very large, solid and heavy shell, with knob-like spines on the shoulder, a flared, thick outer lip, and a characteristic pink or orange aperture (opening). The outside of the queen conch is sandy colored, helping them blend in with their surroundings. The flared lip is absent in juveniles; it develops once the snail reaches reproductive age. The thicker the shell's flared lip is, the older the conch is.[9] The external anatomy of the soft parts of A. gigas is similar to that of other snails in the family Strombidae; it has a long snout, two eyestalks with well-developed eyes, additional sensory tentacles, a strong foot and a corneous, sickle-shaped operculum.

The shell and soft parts of living A. gigas serve as a home to several different kinds of commensal animals, including slipper snails, porcelain crabs and a specialized species of cardinalfish known as the conchfish (Astrapogon stellatus). Its parasites include coccidians. The queen conch's natural predators include several species of large predatory sea snails, octopus, starfish, crustaceans and vertebrates (fish, sea turtles, nurse sharks). It is an especially important food source for large predators like sea turtles and nurse sharks. Human capture and consumption dates back into prehistory.

Its shell is sold as a souvenir and used as a decorative object. Historically, Native Americans and indigenous Caribbean peoples used parts of the shell to create various tools.

International trade in the Caribbean queen conch is regulated under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) agreement, in which it is listed as Strombus gigas.[10] This species is not endangered in the Caribbean as a whole, but is commercially threatened in numerous areas, largely due to extreme overfishing.

Taxonomy and etymology

History

The queen conch was originally described from a shell in 1758 by Swedish naturalist and taxonomist Carl Linnaeus, who originated the system of binomial nomenclature.[2] Linnaeus named the species Strombus gigas, which remained the accepted name for over 200 years. Linnaeus did not mention a specific locality for this species, giving only "America" as the type locality.[12] The specific name is the ancient Greek word gigas (γίγας), which means "giant", referring to the large size of this snail compared with almost all other gastropod molluscs.[13] Strombus lucifer, which was considered to be a synonym much later, was also described by Linnaeus in Systema Naturae.[2]

In the first half of the 20th century, the type material for the species was thought to have been lost; in other words, the shell on which Linnaeus based his original description and which would very likely have been in his own collection, was apparently missing, which created a problem for taxonomists. To remedy this, in 1941 a neotype of this species was designated by the American malacologists William J. Clench and R. Tucker Abbott. In this case, the neotype was not an actual shell or whole specimen, but a figure from a 1684 book Recreatio mentis, et occuli, published 23 years before Linnaeus was born by the Italian Jesuit scholar Filippo Buonanni (1638–1723). This was the first book that was solely about seashells.[12][14][15][16] In 1953 the Swedish malacologist Nils Hjalmar Odhner searched the Linnaean Collection at Uppsala University and discovered the missing type shell, thereby invalidating Clench and Abbott's neotype designation.[17]

Strombidae's taxonomy was extensively revised in the 2000s and a few subgenera, including Eustrombus, were elevated to genus level by some authors.[18][19][20] Petuch[3] and Petuch and Roberts[21] recombined this species as Eustrombus gigas, and Landau and collaborators (2008) recombined it as Lobatus gigas.[20] In 2020, it was recombined as Aliger gigas by Maxwell and colleagues[22], which is the current valid name according to the World Register of Marine Species.[23]

Phylogeny

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A simplified version of the phylogeny and relationships of Strombidae according to Simone (2005)[18] |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phylogeny and relationships of Eastern Pacific and Atlantic Strombus species, according to Latiolais et al. (2006)[19] |

The phylogenetic relationships among the Strombidae were mainly studied by Simone (2005)[18] and Latiolais (2006),[19] using two distinct methods. Simone proposed a cladogram (a tree of descent) based on an extensive morpho-anatomical analysis of representatives of Aporrhaidae, Strombidae, Xenophoridae and Struthiolariidae, which included A. gigas (there referred to as Eustrombus gigas).[18]

With the exception of Lambis and Terebellum, the remaining taxa were previously allocated in the genus Strombus, including A. gigas. However, according to Simone, only Strombus gracilior, Strombus alatus and Strombus pugilis, the type species, remained within Strombus, as they constituted a distinct group based on at least five synapomorphies (traits that are shared by two or more taxa and their most recent common ancestor).[18] The remaining taxa were previously considered subgenera and were elevated to genus level by Simone. Genus Eustrombus (now considered a synonym of Lobatus[24]), in this case, included Eustrombus gigas (now considered a synonym of Aliger gigas) and Eustrombus goliath (= Lobatus goliath), which were thus considered closely related.[18]

In a different approach, Latiolais and colleagues (2006) proposed another cladogram that attempts to show the phylogenetic relationships of 34 species within the family Strombidae. The authors analysed 31 Strombus species, including Aliger gigas (there referred to as Strombus gigas), and three species in the allied genus Lambis. The cladogram was based on DNA sequences of both nuclear histone H3 and mitochondrial cytochrome-c oxidase I (COI) protein-coding gene regions. In this proposed phylogeny, Strombus gigas and Strombus gallus (= Lobatus gallus) are closely related and appear to share a common ancestor.[19]

Common names

Common names include "queen conch" and "pink conch" in English, caracol rosa and caracol rosado in Mexico, caracol de pala, cobo, botuto and guarura in Venezuela, caracol reina, lambí in the Dominican Republic and Grenada,[25][26][27][28][29] and carrucho in Puerto Rico.[30]

Anatomy

Shell

.jpg)

The mature shell grows to 15–31 centimetres (5.9–12.2 in) in length in three to five years[31][32] while the maximum reported size is 35.2 centimetres (13.9 in). However, even though they only grow to be this maximum length, the thickness of the shell is constantly increasing.[1][16][33] The shell is very solid and heavy, with 9 to 11 whorls and a widely flaring and thickened outer lip. The thickness is highly important because the thicker the shell, the better protected it is. Additionally, instead of increasing in size once it reaches its maximum, the outside shell thickens as time goes on- an important indicator of how old the queen conch is.[9] Although this notch is not as well developed as elsewhere in the family,[16] the shell feature is nonetheless visible in an adult dextral (normal right-handed) specimen, as a secondary anterior indentation in the lip, to the right of the siphonal canal (viewed ventrally). The animal's left eyestalk protrudes through this notch.[16][30][34][35]

The spire is a protruding part of the shell that includes all of the whorls except the largest and final whorl (known as the body whorl). It is usually more elongated than in other strombid snails, such as the closely related and larger goliath conch, Lobatus goliath that is endemic to Brazil.[16] In A. gigas, the glossy finish or glaze around the aperture of the adult shell is primarily in pale shades of pink. It may show a cream, peach or yellow colouration, but it can also sometimes be tinged with a deep magenta, shading almost to red. The periostracum, a layer of protein (conchiolin) that is the outermost part of the shell surface, is thin and a pale brown or tan colour.[32][34][35]

The overall shell morphology of A. gigas is not solely determined by the animal's genes; environmental conditions such as location, diet, temperature and depth, and biological interactions such as predation, can greatly affect it.[36][37] Juvenile conches develop heavier shells when exposed to predators. Conches also develop wider and thicker shells with fewer but longer spines in deeper water.[37]

The shells of juvenile queen conches are strikingly different in appearance from those of the adults. Noticeable is the complete absence of a flared outer lip; juvenile shells have a simple sharp lip, which gives the shell a conical or biconic outline. In Florida, juvenile queen conches are known as "rollers", because wave action very easily rolls their shells, whereas it is nearly impossible to roll an adult specimen, due to its shell's weight and asymmetric profile. Subadult shells have a thin flared lip that continues to increase in thickness until death.[38][39][40]

Conch shells are about 95% calcium carbonate and 5% organic matter.[41]

Historic illustrations

Index Testarum Conchyliorum (published in 1742 by the Italian physician and malacologist Niccolò Gualtieri) contains three illustrations of adult shells from different perspectives. The knobbed spire and the flaring outer lip, with its somewhat wing-like contour expanding out from the last whorl, is a striking feature of these images. The shells are shown as if balancing on the edge of the lip and/or the apex; this was presumably done for artistic reasons as these shells cannot balance like this.

One of the most prized shell publications of the 19th century, a series of books titled Illustrations conchyliologiques ou description et figures de toutes les coquilles connues, vivantes et fossiles (published by the French naturalist Jean-Charles Chenu from 1842 to 1853), contains illustrations of both adult and juvenile A. gigas shells and one uncoloured drawing depicting some of the animal's soft parts.[42] Almost forty years later, a colored illustration from the Manual of Conchology (published in 1885 by the American malacologist George Washington Tryon) shows a dorsal view of a small juvenile shell with its typical brown and white patterning.[40]

Adult shell, apical view, Gualtieri, 1742 |

Adult shell, ventral view, Gualtieri, 1742 |

Adult shell, dorsal view, Gualtieri, 1742 |

Juvenile shell, Tryon, 1885 |

Soft parts

Many details about the anatomy of Aliger gigas were not well known until Colin Little's 1965 general study.[43] In 2005, R. L. Simone gave a detailed anatomical description.[18] A. gigas has a long extensible snout with two eyestalks (also known as ommatophores) that originate from its base. The tip of each eyestalk contains a large, well-developed lensed eye, with a black pupil and a yellow iris and a small slightly posterior sensory tentacle.[16][31] Amputated eyes completely regenerate.[44] Inside the mouth of the animal is a radula (a tough ribbon covered in rows of microscopic teeth) of the taenioglossan type.[43] Both the snout and the eyestalks show dark spotting in the exposed areas. The mantle is darkly coloured in the anterior region, fading to light gray at the posterior end, while the mantle collar is commonly orange. The siphon is also orange or yellow.[43] When the soft parts of the animal are removed from the shell, several organs are distinguishable externally, including the kidney, the nephiridial gland, the pericardium, the genital glands, stomach, style sac and the digestive gland. In adult males, the penis is also visible.[43]

Foot/locomotion

The species has a large and powerful foot with brown spots and markings towards the edge, but is white nearer to the visceral hump that stays inside the shell and accommodates internal organs. The base of the anterior end of the foot has a distinct groove, which contains the opening of the pedal gland. Attached to the posterior end of the foot for about one third of its length is the dark brown, corneous, sickle-shaped operculum, which is reinforced by a distinct central rib. The base of the posterior two-thirds of the animal's foot is rounded; only the anterior third touches the ground during locomotion.[18][43] The columella, the central pillar within the shell, serves as the attachment point for the white columellar muscle. Contraction of this strong muscle allows the animal's soft parts to shelter in the shell in response to undesirable stimuli.[43]

Aliger gigas has an unusual means of locomotion, first described in 1922 by George Howard Parker (1864–1955).[45][46] The animal first fixes the posterior end of the foot by thrusting the point of the sickle-shaped operculum into the substrate, then it extends the foot in a forward direction, lifting and throwing the shell forward in a so-called leaping motion. This way of moving is considered to resemble that of pole vaulting,[47] making A. gigas a good climber even of vertical concrete surfaces.[48] This leaping locomotion may help prevent predators from following the snail's chemical traces, which would otherwise leave a continuous trail on the substrate.[49]

Life cycle

Aliger gigas is gonochoristic, which means each individual snail is either distinctly male or distinctly female.[30] Females are usually larger than males in natural populations, with both sexes existing in similar proportion.[50] After internal fertilization,[37] the females lay eggs in gelatinous strings, which can be as long as 75 feet (23 m).[35] These are layered on patches of bare sand or seagrass. The sticky surface of these long egg strings allows them to coil and agglutinate, mixing with the surrounding sand to form compact egg masses, the shape of which is defined by the anterior portion of the outer lip of the female's shell while they are layered.[37][51] Each one of the egg masses may have been fertilized by multiple males.[51] The number of eggs per egg mass varies greatly depending on environmental conditions such as food availability and temperature.[37][51] Commonly, females produce 8–9 egg masses per season,[30][52] each containing 180,000–460,000 eggs,[35] but numbers can be as high as 750,000 eggs.[37] A. gigas females may spawn multiple times during the reproductive season,[35] which lasts from March to October, with activity peaks occurring from July to September.[30]

Queen conch embryos hatch 3–5 days after spawning.[53][54] At the moment of hatching, the protoconch (embryonic shell) is translucent and has a creamy, off-white background color with small, pustulate markings. This coloration is different from other Caribbean Lobatus, such as Lobatus raninus and Lobatus costatus, which have unpigmented embryonic shells.[53] Afterwards, the emerging two-lobed veliger (a larval form common to various marine and fresh-water gastropod and bivalve mollusks)[55] spend several days developing in the plankton, feeding primarily on phytoplankton. Metamorphosis occurs some 16–40 days from the hatching,[37] when the fully grown protoconch is about 1.2 mm high.[50] After the metamorphosis, A. gigas individuals spend the rest of their lives in the benthic zone (on or in the sediment surface), usually remaining buried during their first year of life.[56] The queen conch reaches sexual maturity at approximately 3 to 4 years of age, reaching a shell length of nearly 180 mm and weighing up to 5 pounds.[30][35] Individuals may usually live up to 7 years, though in deeper waters their lifespan may reach 20–30 years[35][37][50] and maximum lifetime estimates reach 40 years.[57] It is believed that the mortality rate tends to be lower in matured conchs due to their thickened shell, but it could be substantially higher for juveniles. Estimates have demonstrated that its mortality rate decreases as its size increases and can also vary due to habitat, season and other factors.[56]

Ecology

Distribution

Aliger gigas is native to the tropical Western Atlantic coasts of North and Central America in the greater Caribbean tropical zone.[35] Although the species undoubtedly occurs in other places, this species has been recorded within the scientific literature as occurring, in:[1][58][59] Aruba, (Netherlands Antilles); Barbados; the Bahamas; Belize; Bermuda; North and northeastern regions of Brazil (though this is contested);[16] Old Providence Island in Colombia; Costa Rica; the Dominican Republic; Panama; Swan Islands in Honduras; Jamaica; Martinique; Alacran Reef, Campeche, Cayos Arcas and Quintana Roo, in Mexico; Puerto Rico; Saint Barthélemy; Mustique and Grenada in the Grenadines; Pinar del Río, North Havana Province, North Matanzas, Villa Clara, Cienfuegos, Holguín, Santiago de Cuba and Guantánamo, in the Turks and Caicos Islands and Cuba; South Carolina, Florida, with the Florida Keys and Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary, in the United States; Carabobo, Falcon, Gulf of Venezuela, Los Roques archipelago, Los Testigos Islands and Sucre in Venezuela; all islands of the United States Virgin Islands.

Habitat

Aliger gigas lives at depths from 0.3–18 m[35] to 25–35 m.[33][54] Its depth range is limited by the distribution of seagrass and algae cover. In heavily exploited areas, the queen conch is more abundant in the deepest range.[54] The queen conch lives in seagrass meadows and on sandy substrate,[50] usually in association with turtle grass (species of the genus Thalassia, specifically Thalassia testudinum[38] and also Syringodium sp.)[36] and manatee grass (Cymodocea sp.).[60] Juveniles inhabit shallow, inshore seagrass meadows, while adults favor deeper algal plains and seagrass meadows.[35][61] The critical nursery habitats for juvenile individuals are defined by a series of characteristics, including tidal circulation and macroalgal production, which together enable high rates of recruitment and survival.[62] A. gigas is typically found in distinct aggregates that may contain several thousand individuals.[37]

Diet

Strombid gastropods were widely accepted as carnivores by several authors in the 19th century, a concept that persisted until the first half of the 20th century. This erroneous idea originated in the writings of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, who classified strombids with other supposedly carnivorous snails. This idea was subsequently repeated by other authors, but had not been supported by observation. Subsequent studies have refuted the concept, proving beyond doubt that strombid gastropods are herbivorous animals.[63] In common with other Strombidae,[19] Aliger gigas is a specialized herbivore,[32] that feeds on macroalgae (including red algae, such as species of Gracilaria and Hypnea),[40] seagrass[60] and unicellular algae, intermittently also feeding on algal detritus.[63][64] The green macroalgae Batophora oerstedii is one of its preferred foods.[35]

Interactions

A few different animals establish commensal interactions with A. gigas, which means that both organisms maintain a relationship that benefits (the commensal) species but not the other (in this case, the queen conch). Commensals of this species include certain mollusks, mainly slipper shells (Crepidula spp.) The porcelain crab Porcellana sayana is also known to be a commensal and a small cardinalfish, known as the conch fish (Astrapogon stellatus),[36] sometimes shelters in the conch's mantle for protection.[35] A. gigas is very often parasitized by protists of the phylum Apicomplexa, which are common mollusk parasites. Those coccidian[65][66] parasites, which are spore-forming, single-celled microorganisms, initially establish themselves in large vacuolated cells of the host's digestive gland, where they reproduce freely.[65][66] The infestation may proceed to the secretory cells of the same organ. The entire life cycle of the parasite typically occurs within a single host and tissue.[65]

Aliger gigas is a prey species for several carnivorous gastropod mollusks, including the apple murex Phyllonotus pomum, the horse conch Triplofusus papillosus, the lamp shell Turbinella angulata, the moon snails Natica spp. and Polinices spp., the muricid snail Murex margaritensis, the trumpet triton Charonia variegata and the tulip snail Fasciolaria tulipa.[16][31][67] Crustaceans are also conch predators, such as the blue crab Callinectes sapidus, the box crab Calappa gallus, the giant hermit crab Petrochirus diogenes, the spiny lobster Panulirus argus and others.[31][67] Sea stars, vertebrates, horse conch, octopus eagle ray, nurse shark, fish (such as the permit Trachinotus falcatus[68] and the porcupine fish Diodon hystrix), loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) and humans also eat the queen conch.[31][67]

Uses

Conch meat has been consumed for centuries and has traditionally been an important part of the diet in many islands in the West Indies and Southern Florida. It is consumed raw, marinated, minced or chopped in a wide variety of dishes, such as salads, chowder, fritters, soups, stew, pâtés and other local recipes.[31][47][60][70] In both English and Spanish-speaking regions, for example in the Dominican Republic, Aliger gigas meat is known as lambí. Although conch meat is used mainly for human consumption, it is also sometimes employed as fishing bait (usually the foot).[57][60] A. gigas is among the most important fishery resources in the Caribbean: its harvest value was US$30 million in 1992,[37] increasing to $60 million in 2003.[71] The total annual harvest of meat of A. gigas ranged from 6,519,711 kg to 7,369,314 kg between 1993 and 1998, later production declined to 3,131,599 kg in 2001.[71] Data about US imports shows a total of 1,832,000 kg in 1998, as compared to 387,000 kg in 2009, a nearly 80% reduction twelve years later.[72]

Queen conch shells were used by Native Americans and Caribbean Indians in a wide variety of ways. South Florida bands (such as the Tequesta), the Carib, the Arawak and Taíno used conch shells to fabricate tools (such as knives, axe heads and chisels), jewelry, cookware and used them as blowing horns.[31][73] In Mesoamerican history, Aztecs used the shell as part of jewelry mosaics such as the double-headed serpent.[74] The Aztecs also believed that the sound of trumpets made from queen conch shells represented divine manifestations, and used them in religious ceremonies.[75] In central Mexico, during rain ceremonies dedicated to Tlaloc, the Maya used conch shells as hand protectors (in a manner similar to boxing gloves) during combat.[75] Ancient middens of L. gigas shells bearing round holes are considered an evidence that pre-Columbian Lucayan Indians in the Bahamas used the queen conch as a food source.[69]

Brought by explorers, queen conch shells quickly became a popular asset in early modern Europe. In the late 17th century they were widely used as decoration over fireplace mantels and English gardens, among other places.[47] In contemporary times, queen conch shells are mainly utilized in handicraft. Shells are made into cameos, bracelets and lamps,[60][76] and traditionally as doorstops or decorations by families of seafaring men.[76] The shell continues to be popular as a decorative object, though its export is now regulated and restricted by the CITES agreement.[31] In modern culture, queen conch shells are often represented in everyday objects such as coins[75][77] and stamps.[78][79]

Very rarely (about 1 in 10,000 conchs),[31] a conch pearl may be found within the mantle.[31][39] Though these pearls occur in a range of colors corresponding to the colors of the interior of the shell, pink specimens are the most valuable.[80] These pearls are considered semi-precious,[16] and a popular tourist curio.[60] The best specimens have been used to create necklaces and earrings. A conch pearl is a non-nacreous pearl (formerly referred to by some sources as a 'calcareous concretion'); it differs from most pearls that are sold as gemstones in that it is not iridescent.[80] The specific weight of the conch pearl is 2.85, notably heavier than any other type. Due to the sensitive nature of the animal and the location of the pearl-forming portion of the snail within the spiral shell, commercial cultivation of pearls is considered virtually impossible.[81]

Research into the conch shell's unique architecture is currently under way at MIT.[82][82]

Status

Threats

Queen conch populations have been rapidly declining throughout the years and have been mostly depleted in some areas in the Caribbean due to the fact that they are highly sought after for their meat and their value.[83] Within the conch fisheries, one of the threats to sustainability stems from the fact that there is almost as much meat in large juveniles as there is in adults, but only adult conchs can reproduce, and thus sustain a population.[70] In many places where adult conchs have become rare due to overfishing, larger juveniles and subadults are taken before they ever mate.

In the United States (Florida), it is currently illegal to gather or pick the queen conch either recreationally or commercially.[84] In other parts of the world where it is legal, only adult conchs can be fished. The rule is to let each conch have ample time to reproduce before taken out of its habitat, potentially leading to a more stable population. However, this rule has not been followed by countless fishers.[83][70][85] On a number of islands, subadults provide the majority of the harvest.[86] The abundance of Aliger gigas is declining throughout its range as a result of overfishing and poaching. Especially because of overfishing, many pockets of conch communities fall below the critical level needed for reproducing. A 2019 study predicted overfishing could lead to the extinction of queen conchs in as little as ten years.[87] Additionally, if the conch fishery collapses, it could potentially leave over 9,000 Bahamian fishers out of work.[83] Trade from many Caribbean countries, such as the Bahamas, Antigua and Barbuda, Honduras, Haiti and the Dominican Republic, is known or thought to be unsustainable.[85] As of 2001, queen conch populations in at least 15 Caribbean countries and states were overfished or overexploited.[85] Illegal harvest, including fishing in foreign waters and subsequent illegal international trade, is a common problem in the region.[57] The Caribbean "International Queen Conch Initiative" is an international attempt at managing this species.[59] On 13 January 2019, the Bahamas' Department of Marine Resources announced it would be making official recommendations to better protect the conch, including ending exports and increasing regulatory staff.[83]

Presently, ocean acidification is another serious threat to the queen conch. Acidity levels are rising and adversely affecting shellfish larvae. Rising atmospheric CO2 levels result in rising levels of carbonic acid in seawater, which is particularly harmful to organisms with calcium carbonate shells and structures. Certain larval stages of shellfish are very sensitive to lower seawater pH.[88]

Conservation

The queen conch fishery is usually managed under the regulations of individual nations. In the United States all taking of queen conch is prohibited in Florida and in adjacent Federal waters. No international regional fishery management organization exists for the whole Caribbean area, but in places such as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands, queen conch is regulated under the auspices of the Caribbean Fishery Management Council (CFMC).[57] In 2014, the Parties to the Convention for the Protection and Development of the Marine Environment of the Wider Caribbean Region (Cartagena Convention) included queen conch in Annex III of its Protocol Concerning Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife (SPAW Protocol). Species included in the Annex III require special measures to be taken to ensure their protection and recovery, and their use is authorised and regulated accordingly.[89][90]

This species has been mentioned in the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) since 1985.[37] In 1992 the United States proposed queen conch for listing in CITES Appendix II, making queen conch the first large-scale fisheries product to be regulated by CITES (as Strombus gigas).[57][91][92] In 1995 CITES began reviewing the biological and trade status of the queen conch under its "Significant Trade Review" process. These reviews are undertaken to address concerns about trade levels in an Appendix II species. Based on the 2003 review,[71] CITES recommended that all countries prohibit importation from Honduras, Haiti and the Dominican Republic, according to Standing Committee Recommendations.[93] Queen conch meat continues to be available from other Caribbean countries, including Jamaica and Turks and Caicos, which operate well-managed queen conch fisheries.[57] For conservation reasons, the Government of Colombia currently bans the commercialisation and consumption of the conch between the months of June and October.[94] The Bahamas National Trust is building awareness by educating teachers and students through workshops and an awareness campaign which includes the catchy pop song Conch Gone.[95]

References

- Rosenberg, G. (2009). "Eustrombus gigas (Linnaeus, 1758)". Malacolog Version 4.1.1: A Database of Western Atlantic Marine Mollusca. Retrieved 27 September 2009.

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema Naturae, 10th ed., vol. 1. 824 pp. Laurentii Salvii: Holmiae (Stockholm, Sweden). p. 745.

- Petuch, E.J. (2004). Cenozoic Seas: The view from Eastern North America. CRC Press. pp. 1–308. ISBN 978-0-8493-1632-6.

- Clench, W. J. (1937). "Descriptions of new land and marine shells from the Bahama Islands." Proceedings of the New England Zoölogical Club 16: 17–26, pl. 1. (Stated date: 5 February 1937.) On pages 18–21, plate 1 figure 1.

- Smith, M. (1940). World Wide Seashells: illustrations, geographical range and other data covering more than sixteen hundred species and sub-species of molluscs (1 ed.). Lantana, Florida: Tropical Photographic Laboratory. pp. 131, 139.

- McGinty, T. L. (1946). "A new Florida Strombus, S. gigas verrilli". The Nautilus 60: 46–48, plates. 5–6: plate 5, figs. 2–3; plate 6, figs. 7–8.

- Burry, L. A. (1949). "Shell Notes". 2. pp. 106–109.

- Petuch, E. J. (1994). Atlas of Florida Fossil Shells. Chicago Spectrum Press: Evanston, Illinois., xii + 394 pp., 100 pls. On page 82, plate 20: figure c.

- "Queen Conch".

- Acosta, Charles C. (2006). "Impending Trade Suspensions of Caribbean Queen Conch under CITES: A Case Study on Fishery Impacts and Potential for Stock Recovery" (PDF). Fisheries. 32 (12): 601–606. doi:10.1577/1548-8446(2006)31[601:ITSOCQ]2.0.CO;2.

- Allmon, W. D. (2007). "The evolution of accuracy in natural history illustration: reversal of printed illustrations of snails and crabs in pre-Linnaean works suggests indifference to morphological detail". Archives of Natural History. 34 (1): 174–191. doi:10.3366/anh.2007.34.1.174.

- Clench, W.J.; Abbott, R.T. (1941). "The genus Strombus in the Western Atlantic". Johnsonia. 1 (1): 1–16.

- Brown, R. W. (1954). Composition of Scientific Words (PDF). Baltimore, Maryland, USA: Published by the author. p. 367.

- Robertson, R. (2012). "Buonanni's Chiocciole (1681)". Digital Collections from the Ewell Sale Stewart Library and Archives. The Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, Philadelphia, USA. Archived from the original on 14 January 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- Buonanni, F. (1684). Recreatio mentis, et oculi in observatione animalium testaceorum Italico sermone primum proposita ... nunc ... Latine oblata centum additis testaceorum iconibus. Romae, Ex typographia Varesii. pp. 531–532.

- Moscatelli, R. (1987). The superfamily Strombacea from Western Atlantic. São Paulo, Brazil: Antonio A. Nanô & Filho Ltda. pp. 53–60.

- Wallin, L. (2001). Catalogue of type specimens 4: Linnaean specimens (PDF). Uppsala, Sweden: Uppsala University Museum of Evolution Zoology section (UUZM). pp. 1–128.

- Simone, L. R.L. (2005). "Comparative morphological study of representatives of the three families of Stromboidea and the Xenophoroidea (Mollusca, Caenogastropoda), with an assessment of their phylogeny" (PDF). Arquivos de Zoologia. 37 (2): 178–180. doi:10.11606/issn.2176-7793.v37i2p141-267. ISSN 0066-7870. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2012.

- Latiolais, J.M.; Taylor, M.S; Roy, K.; Hellberg, M.E. (2006). "A molecular phylogenetic analysis of strombid gastropod morphological diversity" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 41 (2): 436–444. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.05.027. PMID 16839783.

- Landau, B.M.; Kronenberg G.C.; Herbert, G. S. (2008). "A large new species of Lobatus (Gastropoda: Strombidae) from the neogene of the Dominican Republic, with notes on the genus". The Veliger. 50 (1): 31–38. ISSN 0042-3211.

- Petuch, E.J.; Roberts, C.E. (2007). The geology of the Everglades and adjacent areas. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group. pp. 1–212. ISBN 978-1-4200-4558-1.

- Maxwell, S.J.; Dekkers, A.M.; Rymer, T.L.; Congdon, B.C. (2020). "Towards resolving the American and West African Strombidae (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Neostromboidae) using integrated taxonomy". The Festivus. 52 (1): 3–38.

- "Aliger gigas (Linnaeus, 1758)". World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- Lobatus Swainson, 1837 . Retrieved through: World Register of Marine Species on 5 December 2012.

- Rodríguez, B.; Posada, J. (1994). "Revisión histórica de la pesquería del botuto o guarura (Strombus gigas L.) y el alcance de su programa de manejo en el Parque Nacional Archipiélago de Los Roques, Venezuela". In Appeldoorn R.; Rodríguez, B. (eds.). Queen conch biology, fisheries and mariculture. Caracas, Venezuela: Fundación Cientifica Los Roques. pp. 13–24.

- Buitriago, J. (1983). "Cria en cautiverio, del huevo al adulto, del botuto (Strombus gigasL)". Memoria Sociedad de Ciencias Naturales la Salle. 43: 29–39.

- Avalos, D. C. (1988). "Crecimiento y mortalidad de juveniles de Caracol rosado Strombus gigas en Punta Gavilán, Q. Roo". Documentos de Trabajo. 16: 1–16.

- Eustrombus gigas (Linnaeus, 1758) . Retrieved through: World Register of Marine Species on 13 August 2010.

- Posada, J.M.; Ivan, M.R.; Nemeth, M. (1999). "Occurrence, abundance, and length frequency distribution of queen conch, Strombus gigas, (Gastropoda) in shallow waters of the Jaragua National Park, Dominican Republic" (PDF). Caribbean Journal of Science. 35 (1–2): 70–82.

- Davis, M. (2005). "Species Profile: Queen Conch, Strombus gigas" (PDF). SRAC Publication No. 7203. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- Toller, W.; Lewis, K.A. (2003). Queen Conch Strombus gigas (PDF). U.S.V.I. Animal Fact Sheet. 19. U.S.V.I. Department of Planning and Natural Resources Division of Fish and Wildlife.

- Warmke, G.L.; Abbott, R. T. (1975). Caribbean Seashells. Dover Publications, Inc. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-486-21359-0.

- Welch, J. J. (2010). "The "Island Rule" and Deep-Sea Gastropods: Re-Examining the Evidence". PLoS ONE. 5 (1): e8776. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...5.8776W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0008776. PMC 2808249. PMID 20098740.

- Leal, J.H. (2002). "Gastropods" (PDF). In Carpenter, K. E. (ed.). The living marine resources of the Western Central Atlantic. Volume 1: Introduction, molluscs, crustaceans, hagfishes, sharks, batoid fishes and chimaeras. FAO Species Identification Guide for Fishery Purposes. FAO. p. 139.

- Puglisi, M. P. (2008). "Strombus gigas". Smithsonian Marine Station at Fort Pierce. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 30 July 2009. Retrieved 26 October 2009.

- Tewfik, A. (1991)."An assessment of the biological characteristics, abundance, and potential yield of the queen conch (Strombus gigas L.) fishery on the Pedro Bank off Jamaica". Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Masters of Science (Biology). Acadia University, Canada.

- McCarthy, K. (2007). "A review of queen conch (Strombus gigas) life-history. Sustainable Fisheries Division NOAA. SEDAR 14-DW-4.

- Davis, J.E. (2003). "Population assessment of queen conch, Strombus gigas, in the St. Eustatius Marine Park, Netherlands Antilles" Archived 19 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine. St. Eustatius Marine Park.

- Abbott, R.T. (2002). Zim, H. S. (ed.). Seashells of The World. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1-58238-148-0.

- Tryon, G.W. (1885). Manual of Conchology, structural and systematic, with illustrations of the species. Volume 7. Terebridae, Cancellariidae, Strombidae, Cypraeidae, Ovulidae, Cassididae, Doliidae. pp.107;348.

- "Conch shell gives nano insights into composite materials". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- "Chenu's Mollusks (1842–1853)". Digital Collections. The Academy of Natural Sciences. Archived from the original on 14 January 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- Little, C. (1965). "Notes on the anatomy of the queen conch, Strombus gigas". Bulletin of Marine Science. 15 (2): 338–358. abstract.

- Hughes, H.P.I. (1976). "Structure and regeneration of the eyes of strombid gastropods". Cell and Tissue Research. 171 (2): 259–271. doi:10.1007/bf00219410. PMID 975213.

- Coan, E.V.; Kabat, A.R.; Petit, R.E. (2010). 2,400 Years of Malacology (PDF) (7th ed.). American Malacological Society. p. 874.

- Parker, G. H. (1922). "The leaping of the stromb (Strombus gigas Linn.)". Journal of Experimental Zoology. 36 (2): 205–209. doi:10.1002/jez.1400360204. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013.

- Fish and Wildlife Research Institute (2006). "Queen conch: Florida's spectacular sea snail". Sea Stats. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- Hesse, K. O. (1980). "Gliding and climbing behaviour of the queen conch, Strombus gigas" (PDF). Caribbean Journal of Science. 16: 105–108.

- Berg, C.J. (1975). "Behavior and ecology of conch (superfamily Strombacea) on a deep subtidal algal plain". Bulletin of Marine Science. 25 (3): 307–317.abstract.

- Ulrich Wieneke (ed.) Lobatus gigas. In: Gastropoda Stromboidea. modified: 22 November 2008. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- Robertson, R. (1959). "Observations on the spawn and veligers of conchs (Strombus) in the Bahamas". Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London. 33 (4): 164–171.

- Davis, M.; Hesse, C.; Hodgkins, G. (1987). "Commercial hatchery produced queen conch, Strombus gigas, seed for the research and grow-out market". Proceedings of the Gulf and Caribbean Fisheries Institute. 38: 326–335.

- Davis, M.; Bolton, C.A.; Stoner, A.W. (1993). "A comparison of larval development, growth, and shell morphology in three Caribbean Strombus species". The Veliger. 36 (3): 236–244.

- Ehrhardt, N.M.; Valle-Esquivel, M. (2008). Conch (Strombus gigas) Stock Assessment Manual (PDF). U.S. Virgin Islands, Commonwealth of Puerto Rico: Caribbean Fishery Management Council. pp. 128 pp.

- Brusca, R.C.; Brusca, G.J. (2003). Invertebrates (2nd ed.). Sinauer Associates, Inc. p. 936. ISBN 978-0-87893-097-5.

- Medley, P. (2008). Monitoring and managing queen conch fisheries: A manual (PDF). FAO Fisheries Technical Paper. 514. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the Uniteded Nations (FAO). ISBN 978-92-5-106031-5.

- NOAA."Queen Conch (Strombus gigas)". Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- Martin-Mora, E.; James, F. C.; Stoner, A. W. (1995). "Developmental plasticity in the shell of the queen conch Strombus gigas". Ecology. 76 (3): 981–994. doi:10.2307/1939361. JSTOR 1939361.

- "International Queen Conch Initiative". NOAA: Caribbean Fishery Management Council. Retrieved 27 September 2009.

- "Gastropods". FAO Identification Sheets for Fishery Purposes: Western Central Atlantic (fishing area 31). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

- Stoner, A. W. (1988). "Winter mass migration of juvenile queen conch Strombus gigas and their influence on the benthic environment" (PDF). Marine Ecology Progress Series. 56: 99–104. doi:10.3354/meps056099.

- Stoner, A. W. (2003). "What constitutes essential nursery habitat for a marine species? A case study of habitat form and function for queen conch". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 257: 275–289. Bibcode:2003MEPS..257..275S. doi:10.3354/meps257275. ISSN 1616-1599.

- Robertson, R. (1961). "The feeding of Strombus and related herbivorous marine gastropods". Notulae Naturae of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (343): 1–9.

- Stoner, A.; Ray, M. (1996). "Queen conch, Strombus gigas, in fished and unfished locations of the Bahamas: effects of a marine fishery reserve on adults, juveniles, and larval production" (PDF). Fishery Bulletin. 94 (3): 551–565.

- Cárdenas, E.B.; Frenkiel, L.; Zarate, A.Z.; Aranda, D.A. (2007). "Coccidian (Apicomplexa) parasite infecting Strombus gigas Linné, 1758 digestive gland". Journal of Shellfish Research. 26 (2): 319–321. doi:10.2983/0730-8000(2007)26[319:CAPISG]2.0.CO;2.

- Gros, O.; Frenkiel, L.; Aranda, D.A. (2009). "Structural analysis of the digestive gland of the queen conch Strombus gigas Linnaeus, 1758 and its intracellular parasites". Journal of Molluscan Studies. 75 (1): 59–68. doi:10.1093/mollus/eyn041. ISSN 0260-1230.

- Iversen, E.S.; Jory, D.E.; Bannerot, S. P. (1986). "Predation on queen conchs, Strombus gigas, in the Bahamas". Bulletin of Marine Science. 39 (1): 61–75.

- Jory, D.E. (2006). "An incident of predation on queen conch, Strombus gigas L. (Mollusca, Strombidae), by Atlantic permit, Trachinotus falcatus L. (Pisces, Carangidae)". Journal of Fish Biology. 28 (2): 129–131. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1986.tb05149.x. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012.

- Robertson, R. (2011). "Cracking a queen conch (Strombus gigas), vanishing uses, and rare abnormalities" (PDF). American Conchologist. 39 (3): 21–24. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015.

- Isl, The (23 January 2013). "Virgin Islands Vacation Guide & Community". Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- CITES (2003). Review of Significant Trade in specimens of Appendix-II species. (Resolution Conf. 12.8 and Decision 12.75) Archived 7 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Nineteenth meeting of the Animals Committee, Geneva (Switzerland), 18–21.

- NOAA (2009). National Marine Fisheries Service Fisheries Statistics and Economics Division. . Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- Squires, K. (1941). "Pre-Columbian Man in Southern Florida" (PDF). Tequesta (1): 39–46.

- Colin McEwan; Andrew Middleton; Caroline Cartwright; Rebecca Stacey (2006). Turquoise Mosaics from Mexico. Duke University Press. p. 32. ISBN 0-8223-3924-2.

- Todd, J. (2011). "Conch shells on coins" (PDF). American Conchologist. 39 (1): 12–13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015.

- Abbott, R.T.; Morris, P. A. (1995). A Field Guide to Shells. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 184–185. ISBN 978-0-395-69779-5.

- "Palau issues queen conch pearl coin". Coins Weekly. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- "Country: North America, Grenada". Stamp Collectors Catalogue. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- Moscatelli, R. (1992). Seashells on Stamps, Vol. II. Antonio A. Nano & Filho Ltd. p. 439.

- Fritsch, E.; Misiorowski, E.B. (1987). "The History and Gemology of Queen Conch "Pearls"". Gems & Gemology. 23 (4): 208–221. doi:10.5741/gems.23.4.208. ISSN 0016-626X. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013.

- "Conch Pearls: Sunken Treasure from the Caribbean". www.purepearls.com. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- "Conch shells spill the secret to their toughness". MIT News. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- "The Bahamas' iconic conch could soon disappear". 16 January 2019.

- "International Affairs-Queen Conch". United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- Theile, S. (2001). "Queen conch fisheries and their management in the Caribbean" (PDF). Traffic Europe: 1–77.

- Oxenford, H.A.; et al. (2007). Fishing and marketing of queen conch (Strombus gigas) in Barbados (PDF). CERMES Technical Report. 16. University of the West Indies, Barbados: Centre for Resource Management and Environmental Studies.

- Stoner, Allan W.; Davis, Martha H.; Kough, Andrew S. (2019). "Relationships between Fishing Pressure and Stock Structure in Queen Conch (Lobatus gigas) Populations: Synthesis of Long-Term Surveys and Evidence for Overfishing in The Bahamas". Reviews in Fisheries Science & Aquaculture. 27 (1): 51–71. doi:10.1080/23308249.2018.1480008.

- "Ocean Acidification's impact on oysters and other shellfish". www.pmel.noaa.gov. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- "Annexes of the SPAW Protocol". SPAW-RAC's website. National Park of Guadeloupe - SPAW/RAC. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- "SPAW Protocol Annex III" (PDF). SPAW-RAC's website. National Park of Guadeloupe - SPAW/RAC. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- Appendices I, II and III. cites.org website. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- NOAA Fisheries Office of International Affairs website: CITES. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- "Standing Committee Recommendations". CITES Official Documents No 2003/057. 2003. Archived from the original on 21 October 2010. Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- "Vedas Vigentes en el Territorio Colombiano". Instituto Colombiano Agropecuario (Official Website). Ministerio de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural, Colombia. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- "Conchservation - Bahamas National Trust". bnt.bs. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

Further reading

- Coomans H.E. (1965). "Shells and shell objects from an Indian site on Magueyes Island, Puerto Rico". Caribbean Journal of Science 5 (1–2): 15–23. PDF.

- Spade, D.J.; Griffitt, R.J.; Liu, L.; Brown-Peterson, N.J.; Kroll, K.J.; et al. (2010). "Queen Conch (Strombus gigas) Testis Regresses during the Reproductive Season at Nearshore Sites in the Florida Keys". PLoS ONE. 5 (9): e12737. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...512737S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012737. PMC 2939879. PMID 20856805.

- Stoner, A.W.; Waite, J.M. (1991). "Trophic biology of Strombus gigas in nursery habitats: diets and food sources in seagrass meadows". Journal of Molluscan Studies. 57 (4): 451–460. doi:10.1093/mollus/57.4.451.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lobatus gigas. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Aliger gigas |

- Institute, Waitt. "Queen Conch Factsheet". Waitt Institute. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ARKive – images and movies of the queen conch (Strombus gigas)

- Animal Diversity Web: Strombus gigas

- Microdocs: Life cycle of the conch

- Bermuda Department of Conservation Services (includes Queen Conch Recovery Plan)

- Photos of Aliger gigas on Sealife Collection

.jpg)