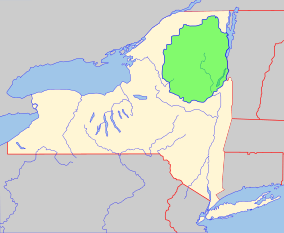

Adirondack Park

The Adirondack Park is a part of New York's Forest Preserve in northeastern New York, United States. The park was established in 1892 for “the free use of all the people for their health and pleasure”, for watershed protection, and as a future timber supply.[2] The park's boundary roughly corresponds with the Adirondack Mountains. Unlike most state parks, about 52 percent of the land is privately owned inholdings. State lands within the park are known as Forest Preserve. Land use on public and private lands in the park are regulated by the Adirondack Park Agency. This area contains 102 towns and villages, as well as numerous farms, businesses, and an active timber harvesting industry.[3] The year-round population is 132,000, with 200,000 seasonal residents. The inclusion of human communities makes the park one of the great experiments in conservation in the industrialized world.[4] The Forest Preserve was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1963.[5]

| Adirondack Park | |

|---|---|

Long Pond, in the Saint Regis Canoe Area. | |

Park area highlighted in green, bounded by the Blue Line, within New York state | |

| Location | New York, United States |

| Area | 9,375 sq mi (24,280 km2) |

| Established | New York State Forest Preserve |

| Named for | Mohawk for tree eaters. |

| Operator | Adirondack Park Agency, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation |

Adirondack Forest Preserve | |

| Area | 2,000,000 acres (8,100 km2) |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000891[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Designated NHL | May 23, 1963 |

The park's 6.1 million acres (2.5×106 ha) include more than 10,000 lakes, 30,000 miles of rivers and streams, and a wide variety of habitats including wetlands and an estimated 200,000 acres of old-growth forests.[6]

History

For the history of the area before the formation of the park, see History of the Adirondack Mountains.

Early tourism

Before the 19th century, the wilderness was viewed as desolate and forbidding. As Romanticism developed in the United States, the view of wilderness became more positive, as seen in the writings of James Fenimore Cooper, Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

The 1849 publication of Joel Tyler Headley's Adirondack; or, Life in the Woods triggered the development of hotels and stage coach lines. William Henry Harrison Murray's 1869 wilderness guidebook depicted the area as a place of relaxation and pleasure rather than a natural obstacle.

Financier and railroad promoter Thomas Clark Durant acquired a large tract of central Adirondack land and built a railroad from Saratoga Springs to North Creek. By 1875, there were more than two hundred hotels in the Adirondacks including Paul Smith's Hotel. About this time, the Great Camps were developed.

Moves to protect New York's water supply

Following the Civil War, Reconstruction Era economic expansion led to an increase in logging and deforestation, especially in the southern Adirondacks.

In 1870 Verplanck Colvin made the first recorded ascent of Seward Mountain[1] during which he saw the extensive damage done by lumbermen. He wrote a report which was read at the Albany Institute and printed by the New York State Museum of Natural History. In 1872 he was named to the newly created post of Superintendent of the Adirondack Survey and given a $1000 budget by the state legislature to institute a survey of the Adirondacks.

In 1873 he wrote a report arguing that if the Adirondack watershed was allowed to deteriorate, it would threaten the viability of the Erie Canal, which was then vital to New York's economy. He was subsequently appointed superintendent of the New York state land survey. In 1873, he recommended the creation of a state forest preserve covering the entire Adirondack region.

Article XIV: forever wild

In 1884, a state legislative commission chaired by botanist Charles Sprague Sargent recommended establishment of a forest preserve, to be "forever kept as wild forest lands."[7] The New York State Legislature subsequently passed a law in 1885 for the preservation of forests which designated all state lands within certain counties in the Adirondacks and Catskills as Forest Preserve to be forever kept as wild forest lands. This forestry law also established a Forest Commission which was charged with care, custody, control and superintendence of the Forest Preserve.[8]

In 1894, Article VII, Section 7, (renumbered in 1938 as Article XIV, Section 1)[9] of the New York State Constitution was adopted, which reads in part:

The lands of the state, now owned or hereafter acquired, constituting the forest preserve as now fixed by law, shall be forever kept as wild forest lands. They shall not be leased, sold or exchanged, or be taken by any corporation, public or private, nor shall the timber thereon be sold, removed or destroyed.

In 1902, the legislature passed a bill defining the Adirondack Park for the first time in terms of the counties and towns within it. In 1912 the legislature further clarified that the park included the privately owned lands within as well as the public holdings.

The restrictions on development and lumbering embodied in Article XIV have withstood many challenges from timber interests, hydropower projects, and large-scale tourism development interests.[10] Further, the language of the article, and decades of legal experience in its defense, are widely recognized as having laid the foundation for the U.S. National Wilderness Act of 1964. As a result of the legal protections, many pieces of the original forest of the Adirondacks have never been logged and are old-growth forest.[11]

20th-century development

Early in the 1900s, recreational use increased dramatically. The State Conservation Department (now the DEC) responded by building more facilities: boat docks, tent platforms, lean-tos, and telephone and electrical lines. With the building of the Interstate 87 in the 1960s, private lands came under great pressure for development. This growing crisis led to the 1971 creation of the Adirondack Park Agency (APA) to develop long-range land-use plans for both the public and private lands within the Blue Line.

In consultation with the DEC, the APA formulated the State Land Master Plan which was adopted into law in 1973. The plan is designed to channel much of the future growth in the Park around existing communities, where roads, utilities, services, and supplies already exist.[12]

In 2008 The Nature Conservancy purchased Follensby Pond – about 14,600 acres (5,900 ha) of private land inside the park boundary – for $16 million.[13] The group plans to sell the land to the state which will add it to the forest preserve once the remaining leases for recreational hunting and fishing on the property expire.[13]

Comparison of the Park in 1900 and 2000

| Year: | 1900 | 2000 |

|---|---|---|

| Area of the Park | 2,800,000 acres (1,100,000 ha) | 5,820,313 acres (2,355,397 ha) |

| State-owned area | 1,200,000 acres (490,000 ha) (43%) | 2,595,859 acres (1,050,507 ha) (44.6%[14]) |

| Travel time, New York City to Old Forge | 6.5 hours by railroad | 5 hours by car |

| Permanent park residents | 100,000 | 130,000 |

| Length of public road in the park | 4,154 miles (6,685 km) plus 500 miles (800 km) of passenger railroad track | 6,970 miles (11,220 km) |

| Industry | 92 sawmills, 15 iron mines, 10 pulp/paper mills | 40 sawmills, 1 pulp/paper mill |

Data compiled by the Adirondack Experience, Blue Mountain Lake, New York

Park management

The park is managed by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation and by the Adirondack Park Agency. This system of management is distinctly different from New York's state park system, which is managed by the Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. According to the State Land Master Plan, state lands are classified.

The Adirondack Park Land Use and Development Plan (APLUDP) applies to private land use and development. It defines APA jurisdiction and is designed to direct and cluster development to minimize impact.

Land use classifications

Areas rounded to the nearest per cent. 49% of the park is privately owned, 45% state owned, and 6% is water.[15]

Private land use

- Resource Management: 51% of private land use. Used for residential, agriculture, and forestry. Most development requires an Agency permit. Limited to an average of 15 buildings per square mile.

- Rural Use: 17%. Most uses are permitted; residential uses and reduced intensity development that preserves rural character is most suitable. Limited to an average of 75 buildings per square mile.

- Low Intensity: 9%. Most uses are permitted; residential development at a lower intensity than hamlet or moderate intensity is appropriate. Limited to an average of 200 of buildings per square mile.

- Moderate Intensity: 3%. Most uses are permitted; residential development is most appropriate. Limited to an average of 500 of buildings per square mile.

- Hamlet: 2%. These are the growth and service centers of the region where the APA encourages development with very limited permit requirements. Activities requiring an APA permit are: erecting buildings or structures over 40 feet high, projects involving more than 100 lots, sites or units, projects involving wetlands, airports, and watershed management projects. Hamlet boundaries usually go well beyond established settlements to provide room for future expansion. There is no limit on the average number of buildings per square mile.

- Industrial: <1%. Where industry exists or has existed, and areas which may be suitable for future development. Industrial and commercial uses are also allowed in other land use area classifications. There is no limit on the average number of buildings per square mile.

Adirondack Park state land use

- Wild forest: 51% of state land use. Areas that have seen higher human impact and can thus withstand a higher level of recreational use. Often these are lands which were logged heavily in the recent past (sometimes right before being transferred to the state). Powered vehicles are allowed.

- Wilderness: 46%. These are managed like federal U.S. Wilderness Areas. Areas far more affected by nature than humanity, to the extent that the latter is practically unnoticeable, for example virgin forest. No powered vehicles are allowed in wilderness areas. Recreation is limited to passive activities such as hiking, camping, hunting, birding and angling which are themselves subject to some further restrictions to ensure that they leave no trace.

- Canoe area: <1%. Lands with a wilderness character that have enough streams, lakes and ponds to provide ample opportunities for water-based recreation. The Saint Regis Canoe Area is the only such designated area in the park.

- Primitive: <1%. Like wilderness, but may have structures that cannot easily be removed, or some other existing use that would complicate a wilderness designation. For most practical purposes there is no difference between a primitive area and a wilderness area.

- Intensive Use: <1%. Places like state campgrounds or day use areas. The developed ski area Whiteface Mountain is in this classification.

- Historic: <1%. Sites of buildings owned by the state that are significant to the history, architecture, archaeology or culture of the Adirondacks, those on the National Register of Historic Places or carrying or recommended for a similar state-level designation.

- State Administrative: <1%. Applies to a limited number of DEC-owned lands that are managed for other than Forest Preserve purposes. It covers a number of facilities devoted to research, and state fish hatcheries.

Advocacy

Private organizations are buying land in order to sell it back to New York State to be added to the public portion of Park.[13] A number of non-governmental organizations work for the park:

- The Adirondack Council, founded in 1975, is the largest citizen environmental group in New York State. Its mission is to ensure the ecological integrity and wild character of the Adirondack Park. It sponsors research, educates the public and policy makers, advocates for policies, and takes legal action when necessary to uphold constitutional protections and agency policies established to protect the Adirondacks.[16]

- Adirondack Wild, whose goal is to uphold the "forever wild", or Article 14 of the New York Constitution.[17]

- The Wildlife Conservation Society's Adirondack Program[18]

- The Adirondack Chapter of the Nature Conservancy.

- The Adirondack Mountain Club has 28,000 members and has an environmental advocacy program that grew out of the need for responsible public policies to protect these lands.

- Founded in 1901, the Association for the Protection of the Adirondacks (AFPA) is the oldest non-profit advocate for the long-term protection and health of the natural and human communities of the Adirondack Park. In 2009 it merged with the Residents' Committee to Protect the Adirondacks (RCPA) and was renamed Protect the Adirondacks![19]

- The Adirondack Research Consortium (ARC) brings together scientists from research organizations and people who work to make the park a better place.

Conservation

The fur trade led to the near extinction of the beaver in 1893.[20] Other species, such as the moose, the wolf, and the cougar were hunted either for their meat, for sport, or because they were seen as a threat to livestock.[20]

Reintroduction efforts for beaver began around 1904 by combining the remaining beaver in the Adirondacks with those of Canada and later on those from Yellowstone.[20] The population quickly grew to around 2000 roughly ten years and around 20,000 in 1921 with the addition of beaver in different areas of the Park.[20] Although this reintroduction was marked as a success, the elevated beaver population was found to have negative economic impacts on waterways and timber sources.[20]

The trend of man attempting to manage nature would continue with the introduction of elk to the Adirondacks, a species that is unclear to have ever previously occupied the region.[20] After two previously failed attempts to introduce elk, in 1903 over 150 elks were reported by the State of New York Forest, Fish, and Game Commission to have been released and surviving in the park. The elk population increased for several years only to decline due to poaching.[20]

To protect and maintain the elk population in the future, the DeBar Mountain Game Refuge was established within the Forest Preserve.[20] This act of preserving the species was motivated for hunting purposes rather than an ecological or natural aspect.[20] The Game Refuge was defined by a wire fence, numerous postings, and caretakers employed by the State.[20] This effort to control nature was also observed in the actions of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), work crews who established access roads and water supply expansion.[20]

A negative result of the CCC coming to the Park was their trapping and killing of "vermin", which were animals such as hawks, owls, fox, and weasels that preyed on other species sought after by hunters and fishermen. This proved to have unanticipated ecological consequences, most notably the overpopulation of deer which was reported by the New York State Conservation Department in 1945.[20]

Ongoing efforts have been made to reintroduce native fauna that had been lost in the park during earlier exploitation. Animals in various stages of reintroduction include the raccoon, moose, black bear, coyote, opossum, beaver, porcupine, fisher, marten, river otter, bobcat, and Canadian lynx. Not all of these restoration efforts have been successful yet. There are 53 known species of mammals that live in the park.[21]

Birds that inhabit this park include the red-tailed hawk, broad-winged hawk, rough-legged hawk, swainson's hawk, Peregrine falcon, osprey, great horned owl, barred owl, screech owl, turkey vulture and raven.

There are more than 3,000 lakes and 30,000 miles (48,000 km) of streams and rivers. Many areas within the park are devoid of settlements and distant from usable roads. The park includes over 2,000 miles (3,200 km) of hiking trails; these trails comprise the largest trail system in the nation.[22]

Tourism and recreation

An estimated 7–10 million tourists visit the park annually. There are numerous accommodations, including cabins, hunting lodges, villas and hotels, in and around Lake Placid, Lake George, Saranac Lake, Old Forge, Schroon Lake and the St. Regis Lakes. Although the climate during the winter months can be severe, with temperatures falling below −30 °F (−34.4 °C), a number of sanatoriums were located there in the early twentieth century because of the positive effect the air had on tuberculosis patients.

Golf courses within the park border include the Ausable Club, the Lake Placid Club, and the Ticonderoga Country Club. Many of the Adirondack Mountains, such as Whiteface Mountain (Wilmington), Mt. Pisgah (Saranac Lake), Gore mountain (North Creek), West mountain (Glen's falls), Hickory (Luzerne), and Mt. Morris (Tupper Lake) have been developed as ski areas.

Hunting and fishing are allowed in the Adirondack Park, although in many places there are strict regulations. Because of these regulations, the large tourist population has not overfished the area, and as such, the brooks, rivers, ponds and lakes are home to large trout and black bass populations. Although restricted from much of the park, snowmobile enthusiasts can ride on a large network of trails.

Cultural

The Adirondack Park Agency visitor interpretive centers are designed to help orient visitors to the park via educational programs, exhibits, and interpretive trails. Educational programs are available for school groups as well as the general public.[23]

The Wild Center in Tupper Lake offers extensive exhibits about the natural history of the region including a 1,000 foot long series of elevated bridges that rise up over the forest on the Center's campus. Many of the exhibits are live and include native turtles, otter, birds, fish and porcupines. The Center, which is open year-round, has trails to a river and pond on its campus.[24]

The Adirondack Experience in Blue Mountain Lake contains an extensive collections about the human settlement of the park.[25]

The Six Nation Indian Museum in Franklin has as a mission to provide education about Iroquois (also known as Haudenosaunee) culture, particularly environmental ethics, and to reinforce traditional values and philosophies. This is done via artifacts, presentations, and hosted visits.[26]

Hiking and rock climbing

The 46 highest mountains in the Adirondack High Peaks were thought to be over 4,000 feet (1,219 m) when climbed by brothers Robert and George Marshall between 1918 and 1924. Surveys have since shown that four of these peaks — Blake Peak, Cliff Mountain, Nye Mountain and Couchsachraga Peak — are in fact just slightly under 4,000 feet (1,219 m). Some hikers try to climb all of the original 46 peaks and there is a Forty Sixers club for those who have done so. Twenty of the 46 mountains remain trailless.

Cliffs with rock climbing[27] and ice climbing routes are scattered throughout the park boundaries.

Watersports

The surface of many of the lakes lies at an elevation above 1,500 ft (457 m); their shores are usually rocky and irregular, and the wild scenery within their vicinity has made them very attractive to tourists. It is the site of the Adirondack Canoe Classic. Flatwater and whitewater canoeing and kayaking are very popular. Hundreds of lakes, ponds, and slow-moving streams link to provide routes ranging from under one mile (1.6 km) to weeklong treks. Whitewater kayaking and canoeing are popular on many free flowing rivers in the Adirondacks, particularly in the spring. Whitewater rafting trips are run in the spring on the Moose River near Old Forge. Raft trips are possible on the Hudson River near North River from April to October due to dam releases provided by the Town of Indian Lake.

Motorboating is formally restricted on only a few bodies of water.

Development and industry

While the park does contain large areas of wilderness, some areas developed to a varying degree.

Census towns with more than 5,000 inhabitants include:

- Tupper Lake

- Ticonderoga

- Dannemora, site of the Clinton Correctional Facility.

- Harrietstown includes Saranac Lake.

- North Elba includes Lake Placid, the Adirondack Regional Airport, and the Lake Placid Olympic Sports Complex.

Interstate 87 or Northway, completed in the 1970s, runs north to south through the eastern edge of the park, connecting Montreal to Upstate New York. The park is traversed by military training routes of the Air National Guard.

There are six business parks in Essex County of which two have certified shovel ready sites. There is also two in Franklin County. There are many maple syrup producers, and their work is documented at the American Maple Museum at Croghan.

Educational institutions include the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry and Paul Smith's College.

Railways

Railways were used extensively from about 1871 to the 1930s for passenger transport and freight. Passenger transport was supplemented by stagecoaches. Rail operators included Chateauguay Railroad,[28] the Adirondack Railway, the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company, Lake Champlain Transportation Company, the New York Central Railroad, Northern Adirondack Railroad Company, Ogdensburg and Lake Champlain Railroad, New York and Ottawa Railway, Mohawk and Malone Railway and Fulton Chain Railway. An early railway was which connected Saratoga Springs, North Creek,[29] Plattsburgh, the Clinton Correctional Facility.

The principal rail company to the major resorts was the New York Central Railroad. Its destinations on its Adirondack Division included Loon Lake, Saranac Lake, Lake Placid, Santa Clara, Tupper Lake, Thendara, Old Forge, and Lake Clear. On the edge of the park boundary are Brandon and St. Regis Falls. North of the park are Moira and Malone. In 1920 there were 10 scheduled passenger train stops in Big Moose.

Starting in the 1930s people began to use automobiles rather than the train. However, through the 1950s and to 1961, daily there was a day train and a night train in each direction to Lake Placid station.[30] Passenger train service ended in 1965.[31] Freight service to and from the Adirondacks also declined after World War II. The Penn Central Transportation Company, successor to the New York Central, continued freight service between New York City and Lake Placid until 1972.

Airports

There are many small airstrips and lakes for seaplanes to land but there is only one commercial airport within the park. The Adirondack Regional Airport sits just outside of the town of Lake Clear, the airport commercial airlines service funded by the government's Essential Air Service program, which provides small communities with nonstop flights to a major cities that could not be supported without be the help of the government funding. Plattsburgh International Airport is located 10 miles (16 km) outside the park.

Architectural heritage

There is an Adirondack architectural style that relates to the rugged style associated with the Great Camps. The builders of these camps used native building materials and sited their buildings within an irregular wooded landscape. These camps for the wealthy were built to provide a primitive, rustic appearance while avoiding the problems of in-shipping materials from elsewhere.

Fire towers

In 1903 and 1908 fires consumed nearly 1 million acres (400,000 hectares) of forest. In 1909, the first Adirondack fire lookout tower, made of logs, was erected on Mount Morris and many others were built over the next several years. From 1916 steel towers were built. At one time or another, there have been fire towers at 57 locations in today's Adirondack Park. The system worked for about 60 years, but has since been replaced by other technologies. Today 34 towers survive in the region and many have been restored and are accessible to the public.[32] Some in the Adirondack Forest Preserve have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places, including those on the following mountains: Arab, Azure, Blue, Hadley, Kane, Loon Lake, Poke-O-Moonshine, St. Regis, Snowy, and Wakely.[5][33]

Industrial

McIntyre Furnace & McNaughton Cottage: an 1853 blast furnace, the 1832 McNaughton Cottage, the remains of the Tahawus Club era buildings, and the early mining-related sites.[34]

Ecclesiastical

St. Regis Presbyterian church: designed by prolific Saranac Lake architect William L. Coulter and built on land donated by Paul Smith. Construction funds came from donations from the congregation, which was largely made up of summer residents. It served as a church from 1899 to 2010.[35]

Infrastructure

The Bow Bridge: The Bow Bridge in Hadley is one of only two parabolic or lenticular truss bridges in the region and one of only about 50 remaining in the country. It was built over the Sacandaga River by the Berlin Iron Bridge Co. in 1885.[35]

Jay Covered Bridge over the Ausable River.[35]

The AuSable Chasm Bridge.

Residential and leisure

The Adirondack lean-to is a three sided log shelter.

Saranac Village at Will Rogers: a Tudor Revival style retirement community, was constructed in 1930 as a tuberculosis treatment facility for vaudeville performers. Due to the subsequent decline of vaudeville performers, and an eventual cure for tuberculosis, its doors closed in 1975. After sitting unused for twenty years, it was bought in 1998 by the Alpine Adirondack Association, LLC and reopened in January 2000 as a retirement community.[35]

Camp Santanoni was once a private estate of approximately 13,000 acres (53 km²), and now is the property of the state, at Newcomb. It was a residential complex of about 45 buildings. Now a National Historic Landmark, this is one of the earliest examples of the Great Camps of the Adirondacks. At the time of completion in 1893, Camp Santanoni was regarded as the grandest of all such Adirondack camps.[35]

Wellscroft, at Upper Jay, is a Tudor Revival–style summer estate home. It is a long, 2 1⁄2-story, building with several projecting bays, porches, gables and dormers, a porte cochere and a service wing. The rear facade features a large semi-circular projection. The first-story exterior is faced in native fieldstone. The interior features a number of Arts and Crafts style design features. Also on the property are a power house, fire house, gazebo, root cellar, reservoir, ruins of the caretaker's house and carriage house, and the remains of the landscaped grounds.[36] It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2004.[5]

Prospect Point Camp: a Great Camp notable for its unusual chalets inspired by European hunting lodges.

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. November 2, 2013.

- Annual Report of the Forest Commission 1892. www.archive.org accessed July 21, 2020

- "Adirondack Park Agency Annual Report 2014" (PDF). APA. Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- Porter, William; Erickson, Jon; Whaley, Ross (2009). The Great Experiment in Cconservation: Voices from the Adirondack Park (1st ed.). Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press. pp. xxvii–xxxiii. ISBN 978-0815632313.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- The Great Forest of the Adirondacks by Barbara McMartin 1994

- Terrie, Phillip G., Forever Wild, Environmental Aesthetics and the Adirondack Forest Preserve. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1985, p. 98, ISBN 0-87722-380-7

- First Annual Report of the New York Forest Commission 1885. www.archive.org accessed July 19, 2020

- McMartin, Barbara (1994), "Introduction", in McMartin, Barbara; Long, James McMartin (eds.), Celebrating the Constitutional Protection of the Forest Preserve: 1894-1994, Silver Bay, New York: Symposium Celebrating the Constitutional Protection of the Forest Preserve, pp. 9–10

- Woodworth, Neil F. (1994), "Recreational Use of the Forest Preserve under the Forever Wild Clause", in McMartin, Barbara; Long, James McMartin (eds.), Celebrating the Constitutional Protection of the Forest Preserve: 1894-1994, Silver Bay, New York: Symposium Celebrating the Constitutional Protection of the Forest Preserve, pp. 27–37

- McMartin, Barbara (1994), The Great Forest of the Adirondacks, Utica, New York: North Country Books, ISBN 0-925168-29-7

- "Adirondack Park History". apa.ny.gov. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- Martin Espinoza (September 18, 2008). "Conservancy Buys Slice of Adirondacks". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 25, 2009. Retrieved September 18, 2008.

- "Adirondack Park Land Usage". Adirondack Park Land Use Classification Statistics - May 25, 2017.

- "Adirondack Park Land Use Classification Statistics May 2017". APA. Retrieved September 7, 2017.

- "About Us". Adirondack Council. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- "ARTICLE XIV New York State Constitution". Adirondack Wild. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- "Adirondack Landscape, USA". Wildlife Conservation Society. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- "History". Protect the Adirondacks!. Retrieved June 21, 2015.

- Omohundro, John; Harris, Glenn R. (2012). An environmental history of New York's north country : the Adirondack Mountains and the St. Lawrence River Valley : case studies and neglected topics (1 ed.). Lewiston, N.Y.: Edwin Mellen Press. pp. 99–111. ISBN 978-0773426283.

- "SUNY-ESF: Adirondack Ecological Center". Esf.edu. Retrieved March 16, 2011.

- Adirondack Park Agency - Maps & Geographic Information Systems (GIS), apa.ny.gov; accessed April 11, 2017.

- "The Center for Nature Interpretation in the Adirondacks". SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry.

- "Wild Center". Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- "Adirondack Experience, The Museum on Blue Mountain Lake". Adirondack Experience. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- "Six Nation Indian Museum". 2019. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- A Guide to Rock Climbing and Bouldering in the Adirondack Park, New York, adirondackrock.com; retrieved July 12, 2013.

- Cameron, Duncan (2013). "Adirondack Railways: Historic Engine of Change". Adirondack Journal of Environmental Studies. 19. Retrieved June 26, 2015.

- Sylvester, Nathaniel Bartlett (1878). History of Saratoga County, New York, with illustrations biographical sketches of some of its prominent men and pioneers. Philadelphia, PA: Everts & Ensign.

- April 1961 New York Central Timetable, Table 22 http://www.canadasouthern.com/caso/ptt/images/tt-0461.pdf

- April 1965 New York Central Timetable http://www.canadasouthern.com/caso/ptt/images/tt-0465.pdf

- "Fire Towers". Adirondack Architectural Heritage. Retrieved June 25, 2015.

- Fire Observation Stations of New York State Forest Preserve MPS

- "Finding Historic Gold in an Adirondack Iron Mine". Open Space Institute. Retrieved June 26, 2015.

- "Saved". Adirondack Architectural Heritage. Retrieved June 26, 2015.

- Steven C. Engelhart and Linda Garofalini (February 2003). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Wellscroft". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Retrieved July 14, 2010. See also: "Accompanying 51 photos".

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Adirondack Park. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Adirondacks. |