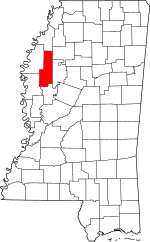

Sunflower County, Mississippi

Sunflower County is a county located in the U.S. state of Mississippi. As of the 2010 census, the population was 29,450.[2] Its largest city and county seat is Indianola.[3]

Sunflower County | |

|---|---|

Sunflower County Courthouse | |

Location within the U.S. state of Mississippi | |

Mississippi's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 33°37′N 90°36′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1844 |

| Named for | Sunflower River[1] |

| Seat | Indianola |

| Largest city | Indianola |

| Area | |

| • Total | 707 sq mi (1,830 km2) |

| • Land | 698 sq mi (1,810 km2) |

| • Water | 9.2 sq mi (24 km2) 1.3% |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 29,450 |

| • Estimate (2018) | 25,735 |

| • Density | 42/sq mi (16/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Congressional district | 2nd |

| Website | www |

Sunflower County comprises the Indianola, MS Micropolitan Statistical Area, which is included in the Cleveland-Indianola, MS Combined Statistical Area. It is located in the Mississippi Delta region.

Mississippi State Penitentiary (Parchman Farm) is located in Sunflower County.

History

Sunflower Country was created in 1844. The land mass encompassed most of Sunflower and Leflore Counties as we know them today. The first seat of government was Clayton, located near Fort Pemberton. Later the county seat was moved to McNutt, also in the Leflore County of today. When Sunflower and Leflore Counties were separated in 1871, the new county seat for Sunflower County was moved to Johnsonville. This village was located where the north end of Mound Bayou empties into the Sunflower River. In 1882 the county seat was moved to Eureka, which was later renamed Indianola.[4]

The Boyer Cemetery, located in Boyer, goes back to the early days of Sunflower County.

After the U.S. Civil War, across several decades African Americans migrated to Sunflower County to work in the Mississippi Delta. In 1870, 3,243 black people lived in Sunflower County. This increased to 12,070 in 1900, making up 75% of the residents in Sunflower County. Between 1900 and 1920, the black population almost tripled.[5]

Many African Americans who had migrated to the North from the 1940s to 1970 in the Great Migration struggled with the loss of jobs in their regions following industrial restructuring. In the 1980s and 1990s, they began to send their children to the Mississippi Delta to live with relatives, thinking social conditions were better than in the inner cities. Gangs and drug trade activity were transported to the Mississippi Delta from northern inner cities. As a result of this trend, crack cocaine began to be distributed in Sunflower County.[6]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 707 square miles (1,830 km2), of which 698 square miles (1,810 km2) is land and 9.2 square miles (24 km2) (1.3%) is water.[7] Sunflower County is the longest county in Mississippi. The traveling distance from the southern boundary at Caile to its northern boundary at Rome is approximately 71 miles.

The center of the county is about 30 miles (48 km) east of the Mississippi River, about 40 miles (64 km) west of the hill section of Mississippi, 100 miles (160 km) north of Jackson, and about 100 miles (160 km) south of Memphis, Tennessee.[8]

Adjacent counties

- Coahoma County (north)

- Tallahatchie County (northeast)

- Leflore County (east)

- Humphreys County (south)

- Washington County (southwest)

- Bolivar County (northwest)

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 1,102 | — | |

| 1860 | 5,019 | 355.4% | |

| 1870 | 5,015 | −0.1% | |

| 1880 | 4,661 | −7.1% | |

| 1890 | 9,384 | 101.3% | |

| 1900 | 16,084 | 71.4% | |

| 1910 | 28,787 | 79.0% | |

| 1920 | 46,374 | 61.1% | |

| 1930 | 66,364 | 43.1% | |

| 1940 | 61,007 | −8.1% | |

| 1950 | 56,031 | −8.2% | |

| 1960 | 45,750 | −18.3% | |

| 1970 | 37,047 | −19.0% | |

| 1980 | 34,844 | −5.9% | |

| 1990 | 32,867 | −5.7% | |

| 2000 | 34,369 | 4.6% | |

| 2010 | 29,450 | −14.3% | |

| Est. 2018 | 25,735 | [9] | −12.6% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[10] 1790-1960[11] 1900-1990[12] 1990-2000[13] 2010-2013[2] | |||

The county reached its peak population in 1930. After that, population declined from 1940 to 1990. There was considerable migration out of the rural county, especially as mechanization reduced the need for farm labor. Both whites and blacks left the county. Many African Americans migrated north or west to industrial cities to escape the social oppression and violence of Jim Crow, especially moving in the Great Migration during and after World War II, when the defense industry on the West Coast attracted many.

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 29,450 people living in the county. 72.9% were black or African American, 25.4% white, 0.3% Asian, 0.2% Native American, 0.6% of some other race and 0.5% of two or more races. 1.4% were Hispanic or Latino (of any race).

As of the census[14] of 2000, there were 34,369 people, 9,637 households, and 7,314 families living in the county. The population density was 50 people per square mile (19/km²). There were 10,338 housing units at an average density of 15 per square mile (6/km²). The racial makeup of the county was 69.86% Black or African American, 28.88% White, 0.09% Native American, 0.40% Asian, 0.48% from other races, and 0.28% from two or more races. 1.30% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

As of the census[14] of 1990, there were 32,341 people. The racial makeup of the county was 71.89% Black or African American, 26.40% White or European American, 0.12% Native American, 0.60% Asian, 0.50% from other races, and 0.28% from two or more races. 1.31% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

As of the census[14] of 1980, there were 30,402 people. The racial makeup of the county was 73.88% Black or African American, 24.45% White or European American, 0.15% Native American, 0.80% Asian, 0.52% from other races, and 0.28% from two or more races. 1.32% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

As of the census[14] of 2000, there were 9,637 households out of which 38.40% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 42.30% were married couples living together, 28.40% had a female householder with no husband present, and 24.10% were non-families. 21.20% of all households were made up of individuals and 9.70% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.01 and the average family size was 3.50.

In the county, the population was spread out with 27.90% under the age of 18, 14.00% from 18 to 24, 30.30% from 25 to 44, 18.10% from 45 to 64, and 9.70% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 30 years. For every 100 females there were 115.90 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 120.00 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $24,970, and the median income for a family was $29,144. Males had a median income of $26,208 versus $19,145 for females. The per capita income for the county was $11,365. About 24.60% of families and 30.00% of the population were below the poverty line, including 39.50% of those under age 18 and 24.10% of those age 65 or over.

Sunflower County has the ninth-lowest per capita income in Mississippi and the 72nd-lowest in the United States.

Government

The Mississippi Department of Corrections (MDOC) is responsible for the state's correctional services, probation services, and parole services. MDOC operates the Mississippi State Penitentiary (MSP; colloquially known as 'Parchman Farm') in the unincorporated community of Parchman in Sunflower County and a probation and parole office in the Courthouse Annex in Indianola.[15]

MSP, a prison for men,[16][17] is the location of the State of Mississippi male death row and the State of Mississippi execution chamber.[18][19] Around the time of MSP's opening in 1901, Sunflower County residents objected to having executions performed at MSP because they feared that Sunflower County would be stigmatized as a "death county." Therefore, the State of Mississippi originally performed executions of condemned criminals in their counties of conviction. By the 1950s residents of Sunflower County were still opposed to the concept of housing the execution chamber at MSP. In September 1954, Governor Hugh White called for a special session of the Mississippi Legislature to discuss the application of the death penalty.[20] During that year, an execution chamber was installed at MSP.[21]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 29.1% 2,794 | 70.1% 6,725 | 0.8% 79 |

| 2012 | 26.1% 2,929 | 73.0% 8,199 | 0.9% 100 |

| 2008 | 29.0% 3,245 | 70.0% 7,838 | 1.0% 110 |

| 2004 | 35.3% 3,534 | 63.5% 6,359 | 1.2% 122 |

| 2000 | 40.0% 3,369 | 59.2% 4,981 | 0.8% 65 |

| 1996 | 35.6% 2,926 | 60.3% 4,960 | 4.1% 339 |

| 1992 | 39.7% 3,726 | 53.8% 5,050 | 6.6% 615 |

| 1988 | 47.0% 4,362 | 52.7% 4,898 | 0.3% 29 |

| 1984 | 51.2% 5,178 | 48.6% 4,913 | 0.2% 20 |

| 1980 | 41.8% 3,728 | 56.4% 5,035 | 1.8% 164 |

| 1976 | 43.1% 3,456 | 53.9% 4,322 | 3.1% 246 |

| 1972 | 73.3% 5,389 | 25.5% 1,874 | 1.3% 92 |

| 1968 | 13.7% 1,036 | 34.4% 2,602 | 51.9% 3,932 |

| 1964 | 94.3% 4,127 | 5.7% 251 | |

| 1960 | 34.1% 1,177 | 29.9% 1,033 | 36.0% 1,241 |

| 1956 | 16.7% 520 | 50.8% 1,585 | 32.5% 1,015 |

| 1952 | 49.5% 2,007 | 50.5% 2,049 | |

| 1948 | 2.1% 55 | 5.1% 136 | 92.9% 2,482 |

| 1944 | 5.3% 155 | 94.8% 2,799 | |

| 1940 | 2.3% 71 | 97.7% 3,071 | |

| 1936 | 0.8% 21 | 99.2% 2,508 | |

| 1932 | 1.4% 34 | 98.4% 2,411 | 0.2% 5 |

| 1928 | 3.2% 88 | 96.8% 2,676 | |

| 1924 | 4.3% 76 | 95.7% 1,694 | |

| 1920 | 4.2% 47 | 95.0% 1,060 | 0.8% 9 |

| 1916 | 2.2% 20 | 97.6% 879 | 0.2% 2 |

| 1912 | 1.8% 9 | 92.4% 462 | 5.8% 29 |

Economy

In December 2011, Sunflower County's unemployment rate was 16.2%. The Mississippi statewide rate was 9.9%, and the U.S. overall unemployment rate was 8.3%.[23]

As of 2012 it was one of the poorest counties in the state,[24] and one of the poorest in the United States.[25]

Transportation

Major highways

Airports

Two airports are located in unincorporated Sunflower County. Indianola Municipal Airport, near Indianola,[26] is operated by the city.[27] Ruleville-Drew Airport, between Drew and Ruleville,[28] is jointly operated by the two cities.[27]

Education

Colleges and universities

Mississippi Delta Community College has a main campus in Moorhead and other locations.

Primary and secondary schools

Public schools

- Public School Districts[29]

- Sunflower County Consolidated School District

- Former districts: Drew School District, Indianola School District, Sunflower County School District

Between 2010 and 2012, the State of Mississippi had taken over all three Sunflower County school districts and put them under the conservatorship of the Mississippi Department of Education,[30] due to academic and financial reasons.[31]

In February 2012 the Mississippi Senate voted 43-4 to pass Senate Bill 2330, to consolidate the three school districts into one school district. The bill went to the Mississippi House of Representatives.[30]

The Greenwood Commonwealth said that the county was an "easy target" for school merging due to the difficulties in all three school districts, and that the scenario "doesn’t leave them with much leverage to argue in favor of the status quo. And because none of them does well, none of them can object to assuming someone else's headaches. All three are beset with them."[32] Later that month, the State Board of Education approved the consolidation of the Drew School District and the Sunflower County School District, and if Senate Bill 2330 is approved, Indianola School District will be added.[33]

In May 2012 Governor of Mississippi Phil Bryant signed the bill into law, requiring all three districts to consolidate.[25] SB2330 stipulates that if a county has three school districts all under conservatorship by the Mississippi Department of Education will have them consolidated into one school district serving the entire county.[34] As of July 1, 2012, the Drew School District was consolidated with the Sunflower County School District.[35]

Private schools

- Private Schools

- Indianola Academy (Indianola)

- North Sunflower Academy (Unincorporated area)[36]

The Central Delta Academy in Inverness closed on May 21, 2010.[37]

All three of the private schools originated as segregation academies.[38][39]

Pillow Academy in unincorporated Leflore County, near Greenwood, enrolls some students from Sunflower County.[40] It originally was a segregation academy.[41]

Media

The Enterprise-Tocsin, a newspaper based out of Indianola, is distributed throughout Sunflower County.[43] The Bolivar Commercial is also distributed in Sunflower County.[44]

Communities

J. Todd Moye, author of Let the People Decide: Black Freedom and White Resistance Movements in Sunflower County, Mississippi, 1945-1986, said "Sunflower County has always been overwhelmingly rural." At the end of the 20th century, the county had just four "main towns of any size."[5]

Towns

Unincorporated communities

Ghost towns

Notable people

- Jerry Butler (Soul singer, inductee Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, born 1939)

- Willie Best (actor, 1916–1962)

- Craig Claiborne (Food Editor, New York Times, 1920–2000)

- James Eastland (U.S. Senator from Mississippi, 1904–1986)

- C. L. Franklin, father of Aretha Franklin

- Fannie Lou Hamer (Civil Rights Activist, Philanthropist, 1917–1977)[45]

- B.B. King (bluesman, 1925–2015)

- Sam Lacey (retired NBA basketball player, 1948–present)

- Archie Manning (NFL quarterback, 1971–1984); father of Peyton Manning, Cooper Manning and Eli Manning

- Charlie Patton (bluesman, 1891–1934)

- Johnny Russell, country singer

See also

References

- Specific

- "Soil survey of Sunflower County, Mississippi". USDA. May 17, 1959 – via Google Books.

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- Hemphill, Marie M. 1980. Fevers, Floods and Faith—A History of Sunflower County Mississippi, 1844–1976

- Moye, J. Todd. Let the People Decide: Black Freedom and White Resistance Movements in Sunflower County, Mississippi, 1945-1986. University of North Carolina Press, November 29, 2004. 28. Retrieved from Google Books on February 26, 2012. ISBN 0-8078-5561-8, ISBN 978-0-8078-5561-4.

- Moye, J. Todd. Let the People Decide: Black Freedom and White Resistance Movements in Sunflower County, Mississippi, 1945-1986. UNC Press Books, 2004. 216. Retrieved from Google Books on March 2, 2011. ISBN 0-8078-5561-8, ISBN 978-0-8078-5561-4.

- "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- "Demographics for Sunflower County Schools." Sunflower County School District. Retrieved on August 17, 2010.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved November 8, 2019.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Sunflower County." Mississippi Department of Corrections. Retrieved on September 14, 2010.

- "State Prisons Archived 2002-12-06 at the Wayback Machine." Mississippi Department of Corrections. Retrieved on May 21, 2010.

- "MDOC QUICK REFERENCE." Mississippi Department of Corrections. Retrieved on May 21, 2010.

- "Division of Institutions State Prisons Archived 2002-12-06 at the Wayback Machine." Mississippi Department of Corrections. April 21, 2010. Retrieved on May 21, 2010.

- Martin, Nathan. "Wilcher gets reprieve Archived 2011-07-13 at Archive.today." Laurel Leader-Call. July 12, 2006. Retrieved on July 21, 2010.

- Cabana, Donald A. "The History of Capital Punishment in Mississippi: An Overview Archived 2010-10-07 at the Wayback Machine." Mississippi History Now. Mississippi Historical Society. Retrieved on August 16, 2010.

- "Mississippi and the Death Penalty Archived 2010-08-11 at the Wayback Machine." Mississippi Department of Corrections. Retrieved on August 12, 2010.

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved 2018-03-04.

- Senate votes to merge 3 Sunflower school districts." Associated Press at gulflive.com, Alabama Live LLC. Wednesday February 8, 2012; retrieved March 25, 2012.

- Matthews, Suzette. "Senate votes to consolidate Sunflower schools." (PDF) The Cleveland Current; retrieved June 13, 2012.

- Wright, Chance. "Bryant signs school merger Archived 2014-06-02 at the Wayback Machine", The Bolivar Commercial; retrieved June 13, 2012.

- FAA Airport Master Record for IDL (Form 5010 PDF) - Retrieved on September 23, 2010.

- "Poplarville, Hattiesburg among airports receiving grants Archived 2012-02-28 at the Wayback Machine." WDAM. March 12, 2010. Retrieved on September 23, 2010.

- FAA Airport Master Record for M37 (Form 5010 PDF) - Retrieved on September 23, 2010.

- "Sunflower County Archived 2011-06-17 at the Wayback Machine." Mississippi Department of Education. Retrieved on July 20, 2010.

- Wright, Chance. "Senate passes school merger Archived 2014-06-02 at the Wayback Machine." Bolivar Commercial. February 2012. Retrieved on March 25, 2012.

- Amy, Jeff. "Miss. bill would force 6 Bolivar County school districts to merge into 3 or fewer." The Republic. March 14, 2012. Retrieved on March 24, 2012.

- "Legislature must initiate school district consolidation." The Greenwood Commonwealth at The Picayune Item. February 17, 2012. Retrieved on March 25, 2012.

- "School consolidation approved", Clarion Ledger, February 17, 2012; retrieved March 26, 2012.

- Doyle, Rory. "Drew, Ruleville prepare to merge Archived 2014-06-02 at the Wayback Machine." Bolivar Commercial. Retrieved on August 30, 2012.

- Amy, Jeff. "Mississippi to return Okolona schools to local control; district merger ends Drew High School." Associated Press at The Republic. May 17, 2012. Retrieved on June 12, 2012.

- "Home." North Sunflower Academy. Retrieved on August 10, 2010.

- "Home Archived 2009-09-05 at the Wayback Machine." Central Delta Academy. Retrieved on August 17, 2010.

- Moye, J. Todd. Let the People Decide: Black Freedom and White Resistance Movements in Sunflower County, Mississippi, 1945-1986. UNC Press Books, 2004. 179. Retrieved from Google Books on March 2, 2011. ISBN 0-8078-5561-8, ISBN 978-0-8078-5561-4.

- Moye, J. Todd. Let the People Decide: Black Freedom and White Resistance Movements in Sunflower County, Mississippi, 1945-1986. UNC Press Books, 2004. 243. Retrieved from Google Books on March 2, 2011. "Sunflower County's two other segregation academies— North Sunflower Academy, between Drew and Ruleville, and Central Delta Academy in Inverness— both sprouted in a similar fashion." ISBN 0-8078-5561-8, ISBN 978-0-8078-5561-4.

- "Profile of Pillow Academy 2010-2011 Archived 2001-12-01 at the Library of Congress Web Archives." Pillow Academy. Retrieved on March 25, 2012.

- Lynch, Adam (18 November 2009). "Ceara's Season". Jackson Free Press. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- "Sunflower County Library Directory." Sunflower County Library. Retrieved on July 21, 2010.

- "about us Archived 2012-03-12 at the Wayback Machine." The Enterprise-Tocsin. Retrieved on March 4, 2011. "Our office is located at 114 Main St, Indianola."

- "bc_masthead1.gif The Bolivar Commercial website; retrieved April 15, 2012.

- Barnwell, p. 225.

- General

- Excerpt of: Mills, Kay This Little Light of Mine. In: Barnwell, Marion (editor) A Place Called Mississippi: Collected Narratives. University Press of Mississippi, 1997. ISBN 1617033391, 9781617033391.

External links

- Sunflower County - State of Mississippi

- Sunflower County Library