Yucatec Maya language

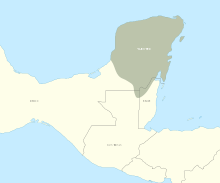

Yucatec Maya (/ˈjuːkəˌtɛk ˈmaɪə/; Yucatec Maya: mayab tʼàan [majaɓˈtʼàːn], mayaʼ tʼàan [majaʔˈtʼàːn], maayaʼ tʼàan [màːjaʔ tʼàːn], literally "flat speech"[4]), is a Mayan language spoken in the Yucatán Peninsula and northern Belize. Native speakers do not qualify it as Yucatec, calling it literally "flat/Maya speech" in their language and simply (el) maya when speaking Spanish.

| Yucatec | |

|---|---|

| Maya | |

| mayaʼ tʼàan maayaʼ tʼàan | |

| Native to | Mexico, Belize |

| Region | Yucatán, Quintana Roo, Campeche, northern Belize |

Native speakers | 792,113 (2010 census)[1] |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Mexico[2] |

| Regulated by | INALI |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | yua |

| Glottolog | yuca1254[3] |

Location of Yucatec Mayan speaking areas on the Yucatan Peninsula | |

Linguists have added Yucatec to the name in order to clearly distinguish it from the rest of Mayan languages (such as Kʼicheʼ and Itzaʼ). Thus the use of the term Yucatec Maya to refer to the language is scholarly or scientific nomenclature.[5]

In the Mexican states of Yucatán, some parts of Campeche, Tabasco, Chiapas, and Quintana Roo, Yucatec Maya is still the mother tongue of a large segment of the population in the early 21st century. It has approximately 800,000 speakers in this region. There are perhaps about 6,000 speakers of Yucatec Maya in Belize.

History

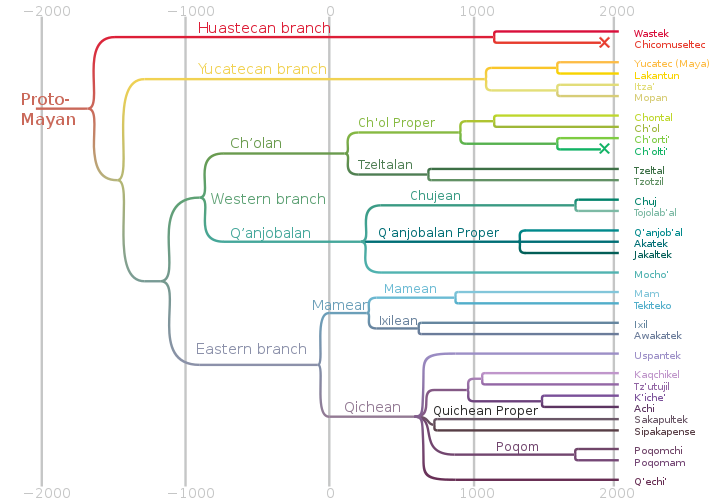

Yucatec Maya forms part of the Yucatecan branch of the Mayan language family. The Yucatecan branch is divided by linguists into the subgroups Mopan-itza and Yucatec-Lacandon. These are made up by four languages:

All the languages in the Mayan language family are thought to originate from an ancestral language that was spoken some 5,000 years ago, known as Proto-Mayan.[6]

Italian explorer Christopher Columbus traded with Maya merchants off the coast of Yucatán during his expedition for the Spanish Crown in 1502, but he never made landfall. During the decade following Columbus's first contact with the Maya, the first Spaniards to set foot on Yucatán soil did so by chance, as survivors of a shipwreck in the Caribbean. The Maya ritually sacrificed most of these men, leaving just two survivors, Gerónimo de Aguilar and Gonzalo Guerrero, who somehow rejoined other Spaniards.[7]

In 1519, Aguilar accompanied Hernán Cortez to the Yucatán island of Cozumel, and also took part in the conquest of central Mexico. Guerrero became a Mexican legend as father of the first Mestizo: by Aguilar's account, Guerrero "went native." He married native women, wore traditional native apparel, and fought against the Spanish.[7]

Francisco de Montejo's military incursion of Yucatán took three generations and three wars with extended fighting, which lasted a total of 24 years.

The Maya had been in a stable decline when Spanish conquistadors arrived in 1517 AD. From 200 to 800 AD the Maya were thriving and making great technological advances. They created a system for recording numerals and hieroglyphs that was more complex and efficient than what had come before. They migrated northward and eastward to the Yucatán peninsula from Palenque, Jaina, and Bonampak. In the 12th and 13th centuries, a coalition emerged in the Yucatán peninsula among three important centers, Uxmal, Chichen Uitza, and Mayapan. The society grew and the people were able to practice intellectual and artistic achievement during a period of peace. When war broke out, such progress was stalled. By the 15th century, Mayan Toltec collapsed and was abandoned.

As the Spanish colonists settled more areas, in the 18th century they developed the lands for large maize and cattle plantations. The elite lived in haciendas and exported natural resources as commodities.[8] The Maya were subjects of the Spanish Empire from 1542 to 1821.

During the colonization of the Yucatán peninsula, the Spanish believed that in order to evangelize and govern the Maya, they needed to reform Yucatec Maya. They wanted to shape it to serve their ends of religious conversion and social control.[9]

Spanish religious missionaries undertook a project of linguistic and social transformation known as reducción (from Spanish reducir). The missionaries translated Catholic Christian religious texts from Spanish into Yucatec Maya and created neologisms to express Catholic religious concepts. The result of this process of reducción was Maya reducido, a semantically transformed version of Yucatec Maya.[9] Missionaries attempted to end Maya religious practices and destroy associated written works. By their translations, they also shaped a language that was used to convert, subjugate, and govern the Maya population of the Yucatán peninsula. But Maya speakers appropriated Maya reducido for their own purposes, resisting colonial domination. The oldest written records in Maya reducido (which used the Roman alphabet) were written by Maya notaries between 1557 and 1851. These works can be found in the United States, Mexico, and Spain in libraries and archives[7]

Phonology

A characteristic feature of Yucatec Maya, like other Mayan languages, is the use of ejective consonants: /pʼ/, /tʼ/, /kʼ/. Often referred to as glottalized consonants, they are produced at the same place of oral articulation as their non-ejective stop counterparts: /p/, /t/, /k/. However, the release of the lingual closure is preceded by a raising of the closed glottis to increase the air pressure in the space between the glottis and the point of closure, resulting in a release with a characteristic popping sound. The sounds are written using an apostrophe after the letter to distinguish them from the plain consonants (tʼàan "speech" vs. táan "forehead"). The apostrophes indicating the sounds were not common in written Maya until the 20th century but are now becoming more common. The Mayan b is also glottalized, an implosive /ɓ/, and is sometimes written bʼ, but that is becoming less common.

Yucatec Maya is one of only three Mayan languages to have developed tone, the others being Uspantek and one dialect of Tzotzil. Yucatec distinguishes short vowels and long vowels, indicated by single versus double letters (ii ee aa oo uu), and between high- and low-tone long vowels. High-tone vowels begin on a high pitch and fall in phrase-final position but rise elsewhere, sometimes without much vowel length. It is indicated in writing by an acute accent (íi ée áa óo úu). Low-tone vowels begin on a low pitch and are sustained in length; they are sometimes indicated in writing by a grave accent (ìi èe àa òo ùu).

Also, Yucatec has contrastive laryngealization (creaky voice) on long vowels, sometimes realized by means of a full intervocalic glottal stop and written as a long vowel with an apostrophe in the middle, as in the plural suffix -oʼob.

Consonants

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m [m] | n [n] | ||||

| Implosive | b [ɓ] | |||||

| Plosive | plain | p [p] | t [t] | k [k] | ʼ [ʔ] | |

| ejective | pʼ [pʼ] | tʼ [tʼ] | kʼ [kʼ] | |||

| Affricate | plain | tz [ts] | ch [tʃ] | |||

| ejective | tzʼ [tsʼ] | chʼ [tʃʼ] | ||||

| Fricative | s [s] | x [ʃ] | j [x] | h [h] | ||

| Approximant | w [w~v]† | l [l] | y [j] | |||

| Flap | r [ɾ] | |||||

† the letter w may represent the sounds [w] or [v]. The sounds are interchangeable in Yucatec Mayan although /w/ is considered the proper sound.

Some sources describe the plain consonants as aspirated, but Victoria Bricker states "[s]tops that are not glottalized are articulated with lung air without aspiration as in English spill, skill, still."[10]

Vowels

In terms of vowel quality, Yucatec Maya has a straight-forward five vowel system:

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u |

| Mid | e | o |

| Open | a | |

For each of these five vowel qualities, the language contrasts four distinct vowel "shapes", i.e. combinations of vowel length, tone, and phonation. In the standard orthography first adopted in 1984,[11] vowel length is indicated by digraphs (e.g. "aa" for IPA [aː]).

| Short, neutral tone | Long, low tone | Long, high tone | Creaky voiced ('glottalized, rearticulated'), long, high tone |

|---|---|---|---|

| pik 'eight thousand' [pik] | miis 'cat' [mìːs] | míis [míːs] 'broom; to sweep' | niʼichʼ [nḭ́ːtʃʼ] 'to get bitten' |

In fast-paced speech, the glottalized long vowels may be pronounced the same as the plain long high vowels, so in such contexts ka’an [ká̰ːn] 'sky' sounds the same as káan [káːn] 'when?'.

Stress

Mayan words are typically stressed on the earliest syllable with a long vowel. If there is no long vowel, then the last syllable is stressed. Borrowings from other languages such as Spanish or Nahuatl are often stressed as in the original languages.

Debuccalization

An important morphophonological process in Yucatec Maya is the dissimilation of identical consonants next to each other by debuccalizing to avoid geminate consonants. If a word ends in one of the glottalized plosives /pʼ tʼ kʼ ɓ/ and is followed by an identical consonant, the final consonant may dispose of its point of articulation and become the glottal stop /ʔ/. This may also happen before another plosive inside a common idiomatic phrase or compound word. Examples: [mayaɓˈtʼàːn] ~ [majaʔˈtʼàːn] 'Yucatec Maya' (literally, "flat speech"), and náak’- [náːkʼ-] (a prefix meaning 'nearby') + káan [ká̰ːn] 'sky' gives [ˈnáːʔká̰ːn] 'palate, roof the mouth' (so literally "nearby-sky").

Meanwhile, if the final consonant is one of the other consonants, it debuccalizes to /h/: nak [nak] 'to stop sth' + -kúuns [-kúːns] (a causative suffix) gives nahkúuns [nahˈkúːns] 'to support sb/sth' (cf. the homophones nah, possessed form nahil, 'house'; and nah, possessed form nah, 'obligation'), náach’ [náːtʃ] 'far' + -chah [-tʃah] (an inchoative suffix) gives náahchah [ˈnáːhtʃah] 'to become distant'.

This change in the final consonant is often reflected in orthographies, so [majaʔˈtʼàːn] can appear as maya’ t’àan, maya t'aan, etc.

Acquisition

Phonology acquisition is received idiosyncratically. If a child seems to have severe difficulties with affricates and sibilants, another might have no difficulties with them while having significant problems with sensitivity to semantic content, unlike the former child.[12]

There seems to be no incremental development in phonology patterns. Monolingual children learning the language have shown acquisition of aspiration and deobstruentization but difficulty with sibilants and affricates, and other children show the reverse. Also, some children have been observed fronting palatoalveolars, others retract lamino-alveolars, and still others retract both.[12]

Glottalization was not found to be any more difficult than aspiration. That is significant with the Yucatec Mayan use of ejectives. Glottal constriction is high in the developmental hierarchy, and features like [fricative], [apical], or [fortis] are found to be later acquired.[13]

Grammar

Like almost all Mayan languages, Yucatec Maya is verb-initial. Word order varies between VOS and VSO, with VOS being the most common. Many sentences may appear to be SVO, but this order is due to a topic–comment system similar to that of Japanese. One of the most widely studied areas of Yucatec is the semantics of time in the language. Yucatec, like many other languages of the world (Kalaallisut, arguably Mandarin Chinese, Guaraní and others) does not have the grammatical category of tense. Temporal information is encoded by a combination of aspect, inherent lexical aspect (aktionsart), and pragmatically governed conversational inferences. Yucatec is unusual in lacking temporal connectives such as 'before' and 'after'. Another aspect of the language is the core-argument marking strategy, which is a 'fluid S system' in the typology of Dixon (1994)[14] where intransitive subjects are encoded like agents or patients based upon a number of semantic properties as well as the perfectivity of the event.

Verb paradigm

| Phase | Example | |

|---|---|---|

| Present | tin (tan-in) het-ik "I am opening something" | |

| Past | Simple | tin (t-in) het-ah "I opened something" |

| Recent | tzʼin (tzʼon-in) het-ah "I have just opened something" | |

| Distant | in het-m-ah "I opened something a long time ago" | |

| Future | Simple | hēn (he-in) het-ik-e "I shall open something" |

| Possible | kin (ki-in) het-ik "I may open something" | |

| Going-to future | bin in het-e "I am going to open something" | |

| Imperative | het-e "Open it! | |

| Phase | Example | |

|---|---|---|

| Present | tin (tan-in) het-el or het-el-in-kah (het-l-in-kah) "I am performing the act of opening" | |

| Past | Simple | het-en or tʼ-het-en "I opened" |

| Recent | tzʼin het-el "I have just opened" | |

| Future | Simple | hēn (he-in) het-el-e "I shall open" |

| Going-to future | ben-het-ăk-en "I am going to open" | |

| Imperative | het-en "Open!" | |

| Phase | Example | |

|---|---|---|

| Present | tun (tan-u) het-s-el "it is being opened" | |

| Past | het-s-ah-b-i or het-s-ah-n-i "it was opened" | |

| Future | hu (he-u) het-s-el-e or bin het-s-ăk-i "it will be opened" | |

| Phase | Example | |

|---|---|---|

| Present | tin (tan-in) kim-s-ik "I am killing something" | |

| Past | Simple | tin (t-in) kim-s-ah "I killed something" |

| Recent | tzʼin (tzʼon-in) kim-s-ah "I have just [killed] something" | |

| Distant | in kim-s-m-ah "I killed something a long time ago" | |

| Future | Simple | hēn (he-in) kim-s-ik-e "I shall kill something" |

| Possible | kin (ki-in) kim-s-ik "I may kill something" | |

| Going-to future | bin in kim-s-e "I am going to kill something" | |

| Imperative | kim-s-e "Kill it! | |

| Phase | Example | |

|---|---|---|

| Present | tin (tan-in) kim-il or kim-il-in-kah "I am dying" | |

| Past | Simple | kim-i or tʼ-kim-i "He died" |

| Recent | tzʼu kim-i "He has just died" | |

| Future | Simple | hēn (he-in) kim-il-e "I shall die" |

| Going-to future | bin-kim-ăk-en "I am going to die" | |

| Imperative | kim-en "Die!" | |

| Phase | Example | |

|---|---|---|

| Present | tin (tan-in) kim-s-il "I am being killed" | |

| Past | kim-s-ah-b-i or kim-s-ah-n-i "he was killed" | |

| Future | hēn (he-in) kim-s-il-e or bin kim-s-ăk-en "I shall be killed" | |

| Phase | Example | |

|---|---|---|

| Present | tin (tan-in) kux-t-al "I am living" | |

| Past | kux-t-al-ah-en or kux-l-ah-en "I lived" | |

| Future | Simple | hēn (he-in) kux-t-al-e "I shall be living" |

| Going-to future | bin kux-tal-ăk-en "I am going to live" | |

| Imperative | kux-t-en or kux-t-al-en "Live!" | |

| Phase | Example | |

|---|---|---|

| Present | tin (tan-in) tzʼon-ik "I am shooting something" | |

| Past | Simple | tin (t-in) tzʼon-ah "I shot something" |

| Recent | tzʼin (tzʼok-in) tzʼon-ah "I have just shot something" | |

| Distant | in tzʼon-m-ah "I shot something a long time ago" | |

| Future | Simple | hēn (he-in) tzʼon-ik-e "I shall shoot something" |

| Possible | kin (ki-in) tzʼon-ik "I may shoot something" | |

| Going-to future | bin in tzʼon-e "I am going to shoot something" | |

| Imperative | tzʼon-e "Shoot it! | |

| Phase | Example | |

|---|---|---|

| Present | tin (tan-in) tzʼon "I am shooting" | |

| Past | Simple | tzʼon-n-ah-en "I shot" |

| Recent | tzʼin (tzʼok-in) tzʼon "I have just shot" | |

| Distant | tzʼon-n-ah-ah-en "I shot a long time ago" | |

| Future | Simple | hēn (he-in) tzʼon-e "I shall shoot" |

| Going-to future | bin-tzʼon-ăk-en "I am going to shoot" | |

| Imperative | tzʼon-en "Shoot!" | |

| Phase | Example | |

|---|---|---|

| Present | tin (tan-in) tzʼon-ol "I am being shot" | |

| Past | tzʼon-ah-b-en or tzʼon-ah-n-en "I was shot" | |

| Future | hēn (he-in) tzʼon-ol-e "I shall be shot" | |

Orthography

The Maya were literate in pre-Columbian times, when the language was written using Maya script. The language itself can be traced back to proto-Yucatecan, the ancestor of modern Yucatec Maya, Itza, Lacandon and Mopan. Even further back, the language is ultimately related to all other Maya languages through proto-Mayan itself.

Yucatec Maya is now written in the Latin script. This was introduced during the Spanish Conquest of Yucatán which began in the early 16th century, and the now-antiquated conventions of Spanish orthography of that period ("Colonial orthography") were adapted to transcribe Yucatec Maya. This included the use of x for the postalveolar fricative sound (which is often written in English as sh), a sound that in Spanish has since turned into a velar fricative nowadays spelled j.

In colonial times a "reversed c" (ɔ) was often used to represent [tsʼ], which is now more usually represented with ⟨dz⟩ (and with ⟨tzʼ⟩ in the revised ALMG orthography).

Examples

| Yucatec Maya | English | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard pronunciation |

Pronunciation of western Yucatán, northern Campeche and Central Quintana Roo |

Normal translation | Literal translation |

| Bix a beel? | Bix a beh? | How are you? | How is your road? |

| Maʼalob, kux teech? | Good, and you? | Not bad, as for you? | |

| Bey xan teen. | Same with me. | Thus also to me. | |

| Tuʼux ka bin? | Where are you going? | Where do you go? | |

| T(áan) in bin xíimbal. | I am going for a walk. | ||

| Bix a kʼaabaʼ? | What is your name? | How are you named? | |

| In kʼaabaʼeʼ Jorge. | My name is Jorge. | My name, Jorge. | |

| Jach kiʼimak in wóol in wilikech. | Pleased to meet you. | Very happy my heart to see you. | |

| Baʼax ka waʼalik? | What's up? | What (are) you saying? What do you say? | |

| Mix baʼal. | Mix baʼah. | Nothing. Don't mention it. |

No thing. |

| Bix a wilik? | How does it look? | How you see (it)? | |

| Jach maʼalob. | Very good. | Very not-bad | |

| Koʼox! | Let's go! (For two people - you and I) | ||

| Koʼoneʼex! | Let's go! (For a group of people) | ||

| Baʼax a kʼáat? | What do you want? | ||

| (Tak) sáamal. | Aasta sáamah. | See you tomorrow. | Until tomorrow. |

| Jach Dios boʼotik. | Thank you. God bless you very much. |

Very much God pays (it). | |

| wakax | cow | ||

Use in modern media and popular culture

Yucatec-language programming is carried by the CDI's radio stations XEXPUJ-AM (Xpujil, Campeche), XENKA-AM (Felipe Carrillo Puerto, Quintana Roo) and XEPET-AM (Peto, Yucatán).

The 2006 film Apocalypto, directed by Mel Gibson, was filmed entirely in Yucatec Maya. The script was translated into Maya by Hilario Chi Canul of the Maya community of Felipe Carrillo Puerto, who also worked as a language coach on the production.

In the video game Civilization V: Gods & Kings, Pacal, leader of the Maya, speaks in Yucatec Maya.

In August 2012, the Mozilla Translathon 2012 event brought over 20 Yucatec Mayan speakers together in a localization effort for the Google Endangered Languages Project, the Mozilla browser, and the MediaWiki software used by Wikipedia and other Wikimedia projects.[16]

Baktun, the "first ever Mayan telenovela," premiered in August 2013.[17][18]

Jesús Pat Chablé is often credited with being one of the first Maya-language rappers and producers.[19]

In the 2018 video game Shadow of the Tomb Raider, the inhabitants of the game’s Paititi region speak in Yucatec Maya (while immersion mode is on).

The modern bible edition, the New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures was released[20] in the Maya language in 2019.[21] It's distributed without charge, both printed and online editions.

On December 4, 2019, the Congress of Yucatan unanimously approved a measure requiring the teaching of the Maya language in schools in the state.[22]

See also

- Yucatec Maya Sign Language

References

- INALI (2012) México: Lenguas indígenas nacionales

- "Ley General de Derechos Lingüisticos Indígenas". Archived from the original on February 8, 2007.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Yucatec Maya". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Bricker, Victoria (1998). Dictionary Of The Maya Language: As Spoken in Hocabá Yucatan. University of Utah Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0874805697.

- "Maya or Mayans? Comment on Correct Terminology and Spellings". OSEA-cite.org. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- "Mayan Language Family | About World Languages". aboutworldlanguages.com. Retrieved 2016-08-02.

- Restall, Matthew (1999). The Maya World Yucatec Culture and Society, 1550-1850. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3658-8.

- "Yucatan History". Institute for the Study of the Americas. Retrieved 2016-08-02.

- Hanks, William F. (2012-01-01). "BIRTH OF A LANGUAGE: The Formation and Spread of Colonial Yucatec Maya". Journal of Anthropological Research. 68 (4): 449–471. doi:10.3998/jar.0521004.0068.401. JSTOR 24394197.

- Bricker, Victoria (1998). Dictionary Of The Maya Language: As Spoken in Hocabá Yucatan. University of Utah Press. p. XII. ISBN 978-0874805697.

- Straight, Henry Stephen (1976) "The Acquisition of Maya Phonology Variation in Yucatec Child Language" in Garland Studies in American Indian Linguistics. pp.207-18

- Straight, Henry Stephen 1976

- Dixon, Robert M. W. (1994). Ergativity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44898-0.

- Tozzer, Alfred M. (1977). A Maya Grammar. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-23465-7.

- Alexis Santos (2013-08-13). "Google, Mozilla and Wikimedia projects get Maya language translations at one-day 'translathon'". Engadget. Retrieved 2012-08-21.

- Munoz, Jonathan (2013-07-09). "First ever Mayan telenovela premieres this summer". Voxxi. Retrieved 2013-08-02.

- Randal C. Archibold (August 1, 2013). "A Culture Clings to Its Reflection in a Cleaned-Up Soap Opera". The New York Times. Retrieved August 2, 2013.

- Agren, David (30 September 2014). "Mayan MCs transform a lost culture into pop culture". Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- "The New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures Released in Maya". Jw.org. November 1, 2019.

- "New World Translation Released in Maya, Telugu, and Tzotzil". jw.org. October 28, 2019.

- "Congreso de Yucatán aprueba enseñanza obligatoria de lengua maya" [Congress of Yucatan approves obligatory instruction in the Maya language], La Jornada (in Spanish), Dec 4, 2019

Sources

- Barrera Vásquez, Alfredo (2001). Diccionario maya : maya-español, español-maya (4 ed.). México: Porrúa. ISBN 970-07-2741-6. OCLC 48778496.

- Blair, Robert W.; Refugio Vermont Salas; Norman A. McQuown (rev.) (1995) [1966]. Spoken Yucatec Maya (Book I + Audio, Lessons I-VI; Book II + Audio, Lessons VII-XII). Program in Latin American Studies. Chapel Hill, NC: Duke University—University of North Carolina.

- Bolles, David (1997). "Combined Dictionary–Concordance of the Yucatecan Mayan Language". Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. (FAMSI) (revised 2003). Retrieved 2007-02-01.

- Bolles, David; Alejandra Bolles (2004). "A Grammar of the Yucatecan Mayan Language". Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. (FAMSI) (revised online edition, 1996 Lee, New Hampshire). The Foundation Research Department. Retrieved 2007-02-01.

- Bricker, Victoria; Eleuterio Poʼot Yah; Ofelia Dzul de Poʼot (1998). A Dictionary of the Maya Language as Spoken in Hocabá, Yucatán. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. ISBN 0-87480-569-4.

- Brody, Michal (2004). The fixed word, the moving tongue: variation in written Yucatec Maya and the meandering evolution toward unified norms (PhD thesis, UT Electronic Theses and Dissertations, Digital Repository ed.). Austin: University of Texas. hdl:2152/1882. OCLC 74908453.

- Coe, Michael D. (1992). Breaking the Maya Code. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05061-9. OCLC 26605966.

- Curl, John (2005). Ancient American Poets - The Songs of Dzitbalche. Tempe: Bilingual Press. ISBN 1-931010-21-8.

- McQuown, Norman A. (1968). "Classical Yucatec (Maya)". In Norman A. McQuown (Volume ed.) (ed.). Handbook of Middle American Indians, Vol. 5: Linguistics. R. Wauchope (General Editor). Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 201–248. ISBN 0-292-73665-7. OCLC 277126.

- Tozzer, Alfred M. (1977) [1921]. A Maya Grammar (unabridged republication ed.). New York: Dover. ISBN 0-486-23465-7. OCLC 3152525.

External links

| Yucatec Maya language test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |

- Yucatec Maya Collection of William Blunk-Fernández and Michael Carrasco at the Archive of the Indigenous Languages of Latin America. Contains six audio recordings totaling 1.5 hours of spoken Yucatec Maya.

- Mesospace Collection of Juergen Bohnemeyer at the Archive of the Indigenous Languages of Latin America. Contains 19 video recordings. Content restricted, but may be available for researcher use.

- Mayan Languages Collection of Victoria Bricker at the Archive of the Indigenous Languages of Latin America. Contains 714 archival files, including audio recordings and transcriptions, from the languages Chʼol, Tzotzil, and Yucatec Maya. The recordings include "(1) histories of the Caste War of Yucatan of 1847-1901 and local manifestations of the Mexican Revolution of 1917-1921; (2) legends; (3) astronomical lore; (4) medical lore; (5) autobiographies; (6) conversations; (7) and songs (both traditional and original) from a number of different towns in the peninsula."

- Yucatec Maya Collection of Melissa Frazier at the Archive of the Indigenous Languages of Latin America. Contains 60 audio recordings of narratives, collected "to establish a collection of spoken Yucatec Maya that will be helpful to anyone who studies the language."

Language courses

In addition to universities and private institutions in Mexico, (Yucatec) Maya is also taught at:

- OSEA - The Open School of Ethnography and Anthropology

- The University of Chicago

- Leiden University, Netherlands

- Harvard University

- Tulane University

- Indiana University (Minority Languages & Culture Program)

- University of Wisconsin–Madison

- The University of North Carolina

- INALCO, Paris, France

Free online dictionary, grammar and texts: