Amuzgo language

Amuzgo is an Oto-Manguean language spoken in the Costa Chica region of the Mexican states of Guerrero and Oaxaca by about 44,000 speakers.[3] Like other Oto-Manguean languages, Amuzgo is a tonal language. From syntactical point of view Amuzgo can be considered as an active language. The name Amuzgo is claimed to be a Nahuatl exonym but its meaning is shrouded in controversy; multiple proposals have been made, including [amoʃ-ko] 'moss-in'.[4]

| Amuzgo | |

|---|---|

| Amuzgoan | |

| Native to | Mexico |

| Region | Guerrero, Oaxaca |

| Ethnicity | Amuzgo people |

Native speakers | 55,588 (2015 census)[1] |

Oto-Manguean

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | Variously:amu – Northern (Guerrero) Amuzgoazm – Ipalapa Amuzgoazg – San Pedro Amuzgos (Oaxaca) Amuzgo |

| Glottolog | amuz1254[2] |

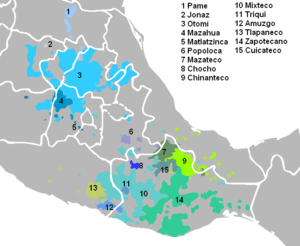

The Amuzgo language, number 12 (darker blue), southwest. | |

A significant percentage of the Amuzgo speakers are monolingual; the remainder also speak Spanish.

Four varieties of Amuzgo are officially recognized by the governmental agency, the Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas (INALI).[5] They are:

- (i) Northern Amuzgo (amuzgo del norte, commonly known as Guerrero or (from its major town) Xochistlahuaca Amuzgo);

- (ii) Southern Amuzgo (amuzgo del sur, heretofore classified as a subdialect of Northern Amuzgo);

- (iii) Upper Eastern Amuzgo (amuzgo alto del este, commonly known as Oaxaca Amuzgo or San Pedro Amuzgos Amuzgo);

- (iv) Lower Eastern Amuzgo (amuzgo bajo del este, commonly known as Ipalapa Amuzgo).

These varieties are very similar, but there is a significant difference between western varieties (Northern and Southern) and eastern varieties (Upper Eastern and Lower Eastern), as revealed by recorded text testing done in the 1970s.[6]

Three dictionaries have been published for Upper Eastern Amuzgo in recent years. For Northern Amuzgo, no dictionary has yet been published, yet it too is very actively written. Lower Eastern Amuzgo and Southern Amuzgo (spoken in Huixtepec (Ometepec), for example) are still not well documented, but work is underway.

While the Mixtecan subdivision may indeed be the closest to Amuzgo within Oto-Manguean,[7] earlier claims that Amuzgo is part of it have been contested.[8]

Phonology

Consonants

The dialect presented in the following chart is Upper Eastern, as spoken in San Pedro Amuzgos as analyzed by Smith & Tapia (2002).

| Bilabial | Dental | Alveolar | Alveopalatal/ Palatal |

Velar | Glottal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ||||||

| Plosive | t | d | tʲ | dʲ | k | ɡ | ʔ | ||

| Affricate | t͡s | t͡ʃ | |||||||

| Fricative | s | ʃ | h | ||||||

| Approximant | j | w | |||||||

The following chart is based on Coronado Nazario et al. (2009) for the variety of Southern Amuzgo spoken in Huixtepec. The phonetic facts are very similar to that of other varieties, but the analysis is different.

| Bilabial | Apico-dental | Apico-lamino-/ alveolar |

Post-alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | n | nʲ | |||||

| Plosive | (p) | t | tʲ | k kʷ ⁿk | ʔ | ||

| Affricate | t͡s | t͡ʃ | |||||

| Fricative | s | ʃ | h | ||||

| Lateral approximant | l | ||||||

| Central approximant | j | w | |||||

| Tap | (ɾ) | ||||||

In this analysis, the nasals and central approximants have distinctive allophones that depend on whether or not they precede a nasalized vowel. The approximant /w/, which is [b] before oral vowels or consonants in Huixtepec, is [m] before nasalized vowels. The approximant /j/ is likewise nasalized before nasalized vowels, and [j] elsewhere. The nasals are pronounced with an oral non-nasal release when they precede an oral vowel, and as such sound like [nd] in that context. Various other important details about the phonetics of Amuzgo are not presented in a simplified chart such as the one shown above.

Vowels

Amuzgo distinguishes seven vowels with respect to quality. In all the documented dialects, all but the two close vowels may be nasalized. Some descriptions claim that Amuzgo also has ballistic syllables, a possible type of supra-glottal phonation. Ballistic syllables are also a feature of the phonology of another Oto-Manguean branch, Chinantec.

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| oral | nasal | oral | nasal | oral | nasal | |

| Close |

i | u | ||||

| Close-mid | e | ẽ | o | õ | ||

| Open-mid | ɛ | ɛ̃ | ɔ | ɔ̃ | ||

| Open |

ɑ | ɑ̃ | ||||

Tones

Amuzgo has three basic tones: high, mid, and low. But it also has several combinations of tones on single syllables. The contour high-low is a common one. The following words are apparently distinguished only by tone in Huixtepec: /ha/ 'sour' (low), /ha/ (mid) 'I', /ha/ (high-low) 'we (exclusive)', and /ha/ (high) 'we (inclusive)'. See also the set: /ta/ 'hill' (low), /ta/ 'thick' (mid), /ta/ ' father (vocative)' (high-low), /ta/ 'slice' (high).[9]

Morphology

Nouns are pluralized by a prefix. The common plural prefix is n-. Compare /thã/ 'skin', /n-thã/ 'skins' (Northern and Southern Amuzgo). Typically the consonant /ts/ drops when the noun is pluralized: /tsʔɔ/ 'hand', /l-ʔɔ/ 'hands' (Northern Amuzgo), /n-ʔɔ/ 'hands' (Southern Amuzgo).

Animate nouns (most animals and insects, plus some other nouns) carry the classifier prefix /ka/. This classifier precedes the inflected noun, as in /ka-tsueʔ/ 'dog', /ka-l-ueʔ/ 'dogs' (Northern Amuzgo), /ka-n-ueʔ/ 'dogs' (Southern Amuzgo).

Syntax

Amuzgo has been proposed to be an active–stative language.[10] Like many other Otomanguean languages, it distinguishes between first person inclusive plural and first person exclusive plural pronouns.

Media

Amuzgo-language programming is carried by the CDI's radio station XEJAM, based in Santiago Jamiltepec, Oaxaca, and by the community radio station Radio Ñomndaa in Xochistlahuaca-Suljaa'.

Notes

- INALI (2012) México: Lenguas indígenas nacionales

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Amuzgoan". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- 2005 census; "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2010-07-21.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Campbell (1997:402)

- Catálogo de las lenguas indígenas nacionales: Variantes lingüísticas de México con sus autodenominaciones y referencias geoestadísticas. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-11-16. Retrieved 2013-07-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link).

- Egland, Bartholomew & Cruz Ramos, 1983:8.

- Campbell (1997:158)

- Longacre (1961, 1966a, 1966b); Longacre & Millon (1961)

- Coronado et al. (2009).

- Smith & Tapia 2002

References

- Bauernschmidt, Amy. 1965. Amuzgo syllable dynamics. Language, 41:471-83.

- Campbell, Lyle. 1997. American Indian languages: the historical linguistics of Native America. Oxford University Press.

- Coronado Nazario, Hilario M.; Ebenecer Coronado Nolasco; Pánfilo de la Cruz Morales; Maurilio Hilario Juárez, & Stephen A. Marlett. 2009. Amuzgo del sur (Huixtepec). Ilustraciones fonéticas de lenguas amerindias, ed. Stephen A. Marlett. Lima: SIL International y Universidad Ricardo Palma..

- Cuevas Suárez, Susana. 1977. Fonología generativa del amuzgo de San Pedro Amuzgos, Oaxaca. Tesis de Licenciatura, Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Mexico City.

- Cuevas Suárez, Susana. 1985. Fonología generativa del amuzgo. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

- Cuevas Suárez, Susana. 1996. Fonología funcional-generativa de una lengua otomangue. In Susana Cuevas and Julieta Haidar (coords.), La imaginación y la inteligencia en el lenguaje: Homenaje a Roman Jakobson. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

- Egland, Steven; Doris Bartholomew & Saúl Cruz Ramos. 1983. La inteligibilidad interdialectal en México: Resultados de algunos sondeos. México, D.F: Instituto Lingüístico de Verano.

- Herrera Zendejas, Esther. 2000. Descripción fonética del amuzgo de Xochistlahuaca, Guerrero. In María del Carmen Morúa Leyva and Gerardo López Cruz (eds.), Memorias del V Encuentro Internacional de Lingüística en el Noroeste, volume 2, 97-116. Hermosillo: Universidad de Sonora.

- Longacre, Robert E. 1961. Swadesh’s Macro-Mixtecan hypothesis. International Journal of American Linguistics, 27:9-29.

- Longacre, Robert E. 1966a. The linguistic affinities of Amuzgo. In Antonio Pompa y Pompa (ed.), Summa anthropologica: En homenaje a Roberto J. Weitlaner. Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. pp. 541–60.

- Longacre, Robert E. 1966b. On linguistic affinities of Amuzgo. International Journal of American Linguistics, 32:46-49.

- Longacre, Robert E. and René Millon. 1961. Proto-Mixtecan and Proto-Amuzgo-Mixtecan vocabularies: a preliminary cultural analysis. Anthropological Linguistics, 3(4):1-44.

- Smith, Thomas C, & Fermin Tapia. 2002, Amuzgo como lengua activa. In Paulette Levy (ed.) Del Cora al Maya Yucateco: estudios lingüisticos sobre algunas lenguas indigenas mexicanas. Mexico City: UNAM.

- Stewart, Cloyd & Ruth D. Stewart, compilers. 2000. Diccionario Amuzgo de San Pedro Amuzgos Oaxaca. Coyoacán, D.F.: Instituto Lingüístico de Verano.

- Tapia García, L Fermín. 1999. Diccionario amuzgo-español: El amuzgo de San Pedro Amuzgos, Oaxaca. Mexico City: Plaza y Valdés Editores.

- Tapia García, Fermín. 2000. Diccionario amuzgo-español. Mexico City: Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social (CIESAS).

- "Estadística básica de la población hablante de lenguas indígenas nacionales 2015". site.inali.gob.mx. Retrieved 2019-10-26.</ref>