Chatino language

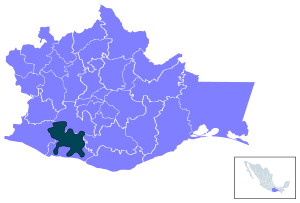

Chatino is a group of indigenous Mesoamerican languages. These languages are a branch of the Zapotecan family within the Oto-Manguean language family. They are natively spoken by 45,000 Chatino people,[2] whose communities are located in the southern portion of the Mexican state of Oaxaca.

| Chatino | |

|---|---|

| Cha'cña | |

| Ethnicity | Chatino people |

| Geographic distribution | Oaxaca, Mexico |

| Linguistic classification | Oto-Manguean

|

| Subdivisions | |

| Glottolog | chat1268[1] |

| |

The Chatinos have close cultural and linguistic ties with the Zapotec people, whose languages form the other branch of the Zapotecan language family. Chatinos call their language chaqF tnyaJ.[lower-alpha 1] Chatino is recognized as a national language in Mexico.

Varieties

The Chatino languages are a group of three languages. Zenzontepec Chatino spoken in about 10 communities in the district of Sola de Vega, Tataltepec Chatino, spoken in Tataltepec the Valdez and a group of language called the Eastern Chatino language spoken in about 15-17 communities. Egland & Bartholomew (1983) conducted mutual intelligibility tests in which they concluded that four varieties of Chatino could be considered separate languages in regards to mutual intelligibility, with 80% intelligibility being needed for varieties to be considered part of the same language. (The same count resulted from a looser 70% criterion.) These were Tataltepec, Zacatepec, Panixtlahuaca, and the Highlands dialects, with Zenzontepec not tested but based on other studies believed to be completely unintelligible with the rest of Chatino. The Highlands dialects fall into three groups, largely foreshadowing the divisions in Ethnologue.

Campbell (2013), in a study based on shared innovations rather than mutual intelligibility, first divides Chatino into two groups—Zenzontepec and Coastal Chatino. He then divides Coastal Chatino into Tataltepec and Eastern Chatino. His Eastern Chatino contains all other varieties and he finds no evidence for subgrouping or further division based on shared innovations. This division mirrors the divisions reported by Boas (1913), based on speaker comments, that Chatino comprised three "dialects" with limited mutual intelligibility. Sullivant (2016) finds that Teojomulco is the most divergent variety.

- Teojomulco

- Core Chatino

- Zenzontepec

- Coastal Chatino

- Tataltepec

- Eastern Chatino

- Zacatepec

- Highlands: Eastern (Lachao-Yolotepec), Western (Yaitepec, Panixtlahuaca, Quiahije), Nopala

Revitalization

The Mexican Secretariat of Education uses a four risk scale to measure endangered languages. The lowest is non-immediate risk of disappearance, then medium risk, high risk, and lastly very high risk of disappearance. Currently, Chatino is considered at high risk of disappearance.

In an effort to help revitalize the Chatino Language, a team of linguists and professors came together to make The Chatino Language Documentation Project. The team included Emiliana Cruz, Hilaria Cruz, Eric Campbell, Justin McIntosh, Jeffrey Rasch, Ryan Sullivant, Stéphanie Villard, and Tony Woodbury. They began the Chatino Documentation Project in the summer of 2003 hoping to document and preserve the Chatino Language and its dialects. Using audio and video recordings they have been able to document the language during everyday life interactions. Up until 2003, Chatino was an oral language, with no written form. After beginning the Chatino Documentation project Emiliana Cruz with the help of the team, began to create a written form of the Chatino Language. This transition has created more resources for revitalization projects. They hope the resources they have made will soon be used to create educational materials like books to help the Chatino people be able to read and write their language.

Phonology and orthography

Yaitepec Chatino has the following phonemic consonants (Pride 1965):

| p, b | t, d | k, ɡ | ʔ |

| w | s, ʃ | h | |

| m | n | ||

| l, r, j |

There are five oral vowels, /i e a o u/, and four nasal vowels, /ĩ ẽ õ ũ/.

Rasch (2002) reports ten distinct tones for Yaitepec Chatino. The level tones are high /1/, mid /2/, low-mid /3/, and low /4/. There are also two rising tones (/21/ and /32/) and three falling tones (/12/, /23/, /34/) as well as a more limited falling tone /24/, found in a few lexical items and in a few Completive forms of verbs.

There are a variety of practical orthographies for Chatino, most influenced by Spanish orthography. In the examples below, ⟨x⟩ represents /ʃ/, ⟨ch⟩ = /tʃ/, and /k/ is spelled ⟨c⟩ before back vowels and ⟨qu⟩ before front vowels.

Morphology

Transitive-Intransitive alternations

Chatino languages have some regular alternations between transitive and intransitive verbs. In general this change is shown by altering the first consonant of the root, as in the following examples from Tataltepec Chatino:

| gloss | transitive | intransitive |

|---|---|---|

| 'change' | ntsa'a | ncha'a |

| 'finish | ntyee | ndyee |

| 'put out' | nxubi' | ndyubi' |

| 'scare' | nchcutsi | ntyutsi |

| 'melt' | nxalá | ndyalá |

| 'throw' | nchcuaa | ndyalu |

| 'bury' | nxatsi | ndyatsi |

| 'frighten' | ntyutsi | nchcutsi |

| 'move' | nchquiña | nguiña |

| 'roast' | nchqui'i | ngui'i |

Causative alternations

There is also a morphological causative in Chatino, expressed by the causative prefix /x-/, /xa-/, /y/, or by the palatalization of the first consonant. The choice of prefix appears to be partially determined by the first consonant of the verb, though there are some irregular cases. The prefix /x/ occurs before some roots that start with one of the following consonants: /c, qu, ty/ or with the vowels /u,a/, e.g.

| catá chcu | 'bathe (reflexive)' | xcatá ji'i | 'bathe (transitive)' |

| quityi | 'dry (reflexive)' | xquityi ji'i | 'dry (tr)' |

| ndyu'u | 'is alive' | nxtyu'u ji'i | 'waken' |

| ndyubi' | 'is put out' | nxubi' | 'put out' |

| tyatsi' | 'is buried' | xatsi' | 'bury' |

The prefix /xa/ is put before certain roots that begin with /t/, e.g.

| nduu | 'is stopping' | nxatuu | 'to stop something' |

Palatalization occurs in some roots that begin with /t/, e.g.

taa 'will give' tyaa 'will pay'

(Pride 1970: 95-96)

The alternations seen here are similar to the causative alternation seen in the related Zapotec languages.

Aspect

Aspect:

Pride (1965) reports eight aspects in Yaitepec Chatino.

potential 'The majority of the verbs have no potential prefix, and its absence indicates this aspect.'

habitual This is indicated by the prefixes /n-, nd-, l-/ and /n-/ with palatalization of the first consonant of the root, e.g.:

nsta 'puts it in' nsta chcubi loo mesa 'puts the box on the table'

ndu'ni cu'na 'graze'

Ndu'ni ngu' cu'na quichi re 'The people of this town graze'

ntya 'sow'

Ntya ngu' quichi re quiña' 'The people of this town sow chile.'

continuative Roots that take /n-/ or /nd-/ in the habitual have the same in the continuative plus palatalization; roots that have /n-/ plus palatalization in the habitual have /ndya-/, e.g. Nxtya chcubi loo mesa 'is putting the box on the table'

Ndyu'ni ngu' cu'na quichi re 'The people of this town are grazing.'

Ndyata ngu' quichi re quiña' 'The people of this town are sowing chile.'

completive This is indicated with the prefix /ngu-/, and verbs that start with /cu-, cui-, qui-/ change to /ngu-/ and /ngüi-/ in the completive:

sta 'will put it' Ngu-sta chcubi loo mesa 'Someone put the box on the table'

culu'u 'will teach it' Ngulu'u mstru ji'i 'The teacher taught it.'

imperative This aspect is indicated by palatalization in the first consonant of the potential form of the verb. If the potential is already a palatalized consonant, the imperative is the same, e.g.:

sati' 'will slacken' xati' ji'i 'let it loose!' xi'yu 'will cut' xi'yu ji'i 'cut it!'

perfective This aspect is indicated by the particle /cua/, which is written as a separate word in Pride (1965).

tyee 'will end' cua tyee ti 'is ended' cua ndya ngu' 'is gone'

passive potential /tya-/

Tyaala ton'ni'i 'The door will be opened.'

passive completive /ndya-/

Ndyaala ton'ni'i 'The door is open.'

Syntax

Chatino languages usually have VSO as their predominant order, as in the following example:

| N-da | nu | xni' | ndaha | ska | ha | xtlya | ?i | nu | 'o. |

| con-give | the | dog | lazy | one | tortilla | Spanish | to | the | coyote |

'The lazy dog gave a sweetbread to the coyote.'

Use and media

Chatino-language programming is carried by the CDI's radio station XEJAM, based in Santiago Jamiltepec, Oaxaca.

In 2012, the Natividad Medical Center of Salinas, California had trained medical interpreters bilingual in Chatino as well as in Spanish;[3] in March 2014, Natividad Medical Foundation launched Indigenous Interpreting+, "a community and medical interpreting business specializing in indigenous languages from Mexico and Central and South America," including Chatino, Mixtec, Trique, and Zapotec.[4][5]

See also

- Chatino Sign Language, used in the Western Highland Chatino villages of San Juan Quiahije and Cieneguilla

Bibliography

- Boas, Franz. 1913. "Notes on the Chatino language of Mexico," American Anthropologist, n.s., 15:78-86.

- Campbell, Eric. 2013. "The Internal Diversification and Subgrouping of Chatino," International Journal of American Linguistics 79:395-420.

- Cruz, Emiliana. 2004. The phonological patterns and orthography of San Juan Quiahije Chatino. University of Texas Masters Thesis. Austin.

- Cruz, Emiliana and Anthony C Woodbury. 2014. Finding a way into a family of tone languages: The story and methods of the Chatino Language Documentation Project. Language Documentation & Conservation 8: 490—524. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24615

- Cruz, Hilaria. 2015. Linguistic poetic and rhetoric of Eastern Chatino of San Juan Quiahije (Ph.D thesis, University of Texas at Austin).

- Egland, Steven, Doris Bartholomew & Saúl Cruz Ramos. 1978. La inteligibilidad interdialectal de las lenguas indígenas de México: Resultado de algunos sondeos. Mexico City: Instituto Lingüístico de Verano. (1983 reprint https://web.archive.org/web/20140907031734/http://www-01.sil.org/mexico/sondeos/G038b-SondeosInteligibilidad.pdf )

- Pride, Kitty. 1965. Chatino syntax. SIL Publications in Linguistics #12.

- Pride, Leslie and Kitty. 1970. Vocabulario Chatino de Tataltepec. Serie de vocabularios indigenas mariano silva y aceves, no. 15. Summer Institute of Linguistics.

- Rasch, Jeffrey Walker. 2002. The basic morpho-syntax of Yaitepec Chatino. Ph.D. thesis. Rice University.

- Sullivant, J. Ryan. 2016. "Reintroducing Teojomulco Chatino," International Journal of American Linguistics 82:393-423.

- Villard S. Grammatical sketch of Zacatepec Chatino. Master's thesis, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas. 2008.

Notes

- chaqF means "word," but Chatinos do not agree on the meaning of tnyaJ. For communities such as Zenzontepec, in San Juan Quiahije, it means 'low', while in Santiago Yaitepec it means 'spicy'. Its meaning is not recoverable in San Marcos Zacatepec or Santa Maria Yolotepec.

References

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Chatino". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- INALI (2012) México: Lenguas indígenas nacionales

- Melissa Flores (2012-01-23). "Salinas hospital to train indigenous-language interpreters". HealthyCal.org. Archived from the original on 2012-01-29. Retrieved 2012-08-05.

- "Natividad Medical Foundation Announces Indigenous Interpreting+ Community and Medical Interpreting Business". Market Wired. 2014-03-07. Retrieved 2014-03-13.

- Almanzan, Krista (2014-03-27). "Indigenous Interpreting Program Aims to be Far Reaching". 90.3 KAZU. Retrieved 2014-04-06.

External links

- Chatino Indian Language at native-languages.org

- Resources on the Chatino languages at the website of the Chatino Language Documentation Project

- Audio recordings of narratives, ceremonies, conversations, music, etc. in Amialtepec, San Juan Quiahije, Yolotepec, and Zacatepec Chatino from the Chatino Documentation of Hilaria Cruz at AILLA.