Yangzhou

Yangzhou, postal romanization Yangchow, is a prefecture-level city in central Jiangsu Province, China. Sitting on the north bank of the Yangtze, it borders the provincial capital Nanjing to the southwest, Huai'an to the north, Yancheng to the northeast, Taizhou to the east, and Zhenjiang across the river to the south. Its population was 4,414,681 at the 2010 census and its urban area is home to 2,146,980 inhabitants, including three urban districts, currently in the agglomeration.

Yangzhou 扬州市 Yangchow | |

|---|---|

Five Pavilion Bridge at the Slender West Lake | |

| |

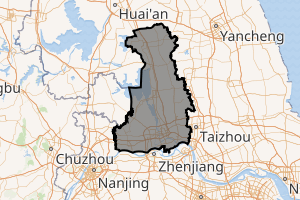

Location of Yangzhou administrative area in Jiangsu | |

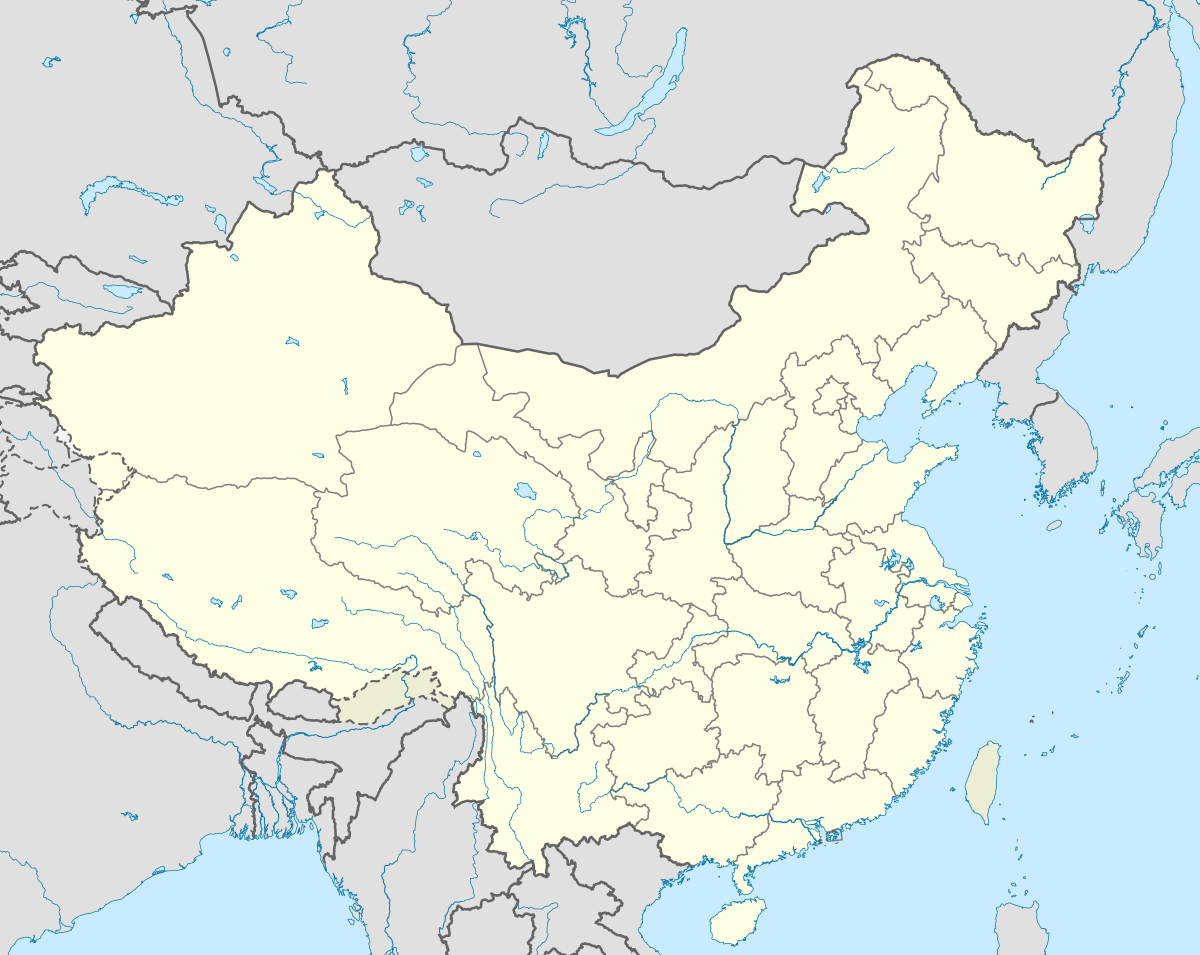

Yangzhou Location of the city center in Jiangsu  Yangzhou Yangzhou (Eastern China)  Yangzhou Yangzhou (China) | |

| Coordinates (Yangzhou municipal government): 32°23′40″N 119°24′46″E | |

| Country | People's Republic of China |

| Province | Jiangsu |

| County-level divisions | 6 (3 Districts, 2 County-level cities, 1 County) |

| Municipal seat | Hanjiang District |

| Government | |

| • Communist Party Chief | Xie Zhengyi (谢正义) |

| • Mayor | Xia Xinmin (夏心旻) |

| Area | |

| • Prefecture-level city | 6,678 km2 (2,578 sq mi) |

| • Urban (2018)[1] | 363 km2 (140 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,310 km2 (890 sq mi) |

| Population (2010 census) | |

| • Prefecture-level city | 4,459,760 |

| • Density | 670/km2 (1,700/sq mi) |

| • Urban (2018)[1] | 1,665,000 |

| • Urban density | 4,600/km2 (12,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,146,980 |

| • Metro density | 930/km2 (2,400/sq mi) |

| Includes only those with Hukou permits | |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (Beijing Time) |

| Telephone | (0)514 |

| ISO 3166 code | CN-JS-10 |

| Licence plate prefixes | 苏K |

| Website | yangzhou |

| Yangzhou | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.svg.png) "Yangzhou" in Simplified (top) and Traditional (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 扬州 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 揚州 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Yang Prefecture" | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Historically, Yangzhou was one of the wealthiest cities in China, known at various periods for its great merchant families, poets, artists, and scholars. Its name (lit. "Rising Prefecture") refers to its former position as the capital of the ancient Yangzhou prefecture in imperial China. Yangzhou was one of the first cities to benefit from one of the earliest world bank loans in China, used to construct Yangzhou thermal power station in 1994.[2][3]

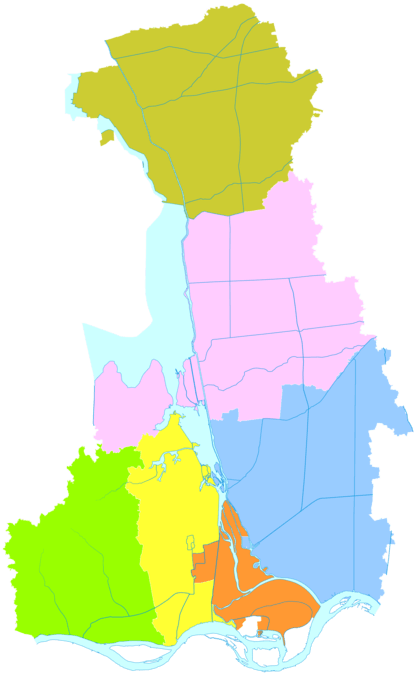

Administration

Currently, the prefecture-level city of Yangzhou administers six county-level divisions, including three districts, two county-level cities and one county. Accordingly, they are further divided into 98 township-level divisions, including 87 towns and townships, and 11 subdistricts.

| Map | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subdivision | Simplified Chinese | Hanyu Pinyin | Population (2010) | Area (km2) | Density (/km2) |

| City Proper | |||||

| Guangling District | 广陵区 | Guǎnglíng Qū | 340,977 | 423.09 | 805.92 |

| Hanjiang District | 邗江区 | Hánjiāng Qū | 1,051,322 | 552.68 | 1,902.23 |

| Suburban | |||||

| Jiangdu District | 江都区 | Jiāngdū Qū | 1,006,780 | 1,329.90 | 757.03 |

| Rural | |||||

| Baoying County | 宝应县 | Bǎoyìng Xiàn | 752,074 | 1,461.55 | 514.57 |

| Satellite cities (County-level cities) | |||||

| Yizheng | 仪征市 | Yízhēng Shì | 563,945 | 902.20 | 625.08 |

| Gaoyou | 高邮市 | Gāoyóu Shì | 744,662 | 1,921.78 | 387.49 |

| Total | 4,459,760 | 6,591.21 | 676.62 | ||

| In November 2011, Weiyang District (维扬区) was merged into Hanjiang District, while the former county-level Jiangdu City became Jiangdu District.[4] | |||||

History

Guangling (Chinese: 廣陵; pinyin: Guǎnglíng; Wade–Giles: Kuang-Ling), the first settlement in the Yangzhou area, was founded in the Spring and Autumn period. After the defeat of Yue by King Fuchai of Wu, a garrison city was built 12 m (39 ft) above the water level on the north bank of the Yangtze c. 485 BC. This city in the shape of a three by three li square was named Hancheng.[5] The newly built Han canal formed a moat around the south and east sides of the city. The purpose of Hancheng was to protect Suzhou from naval invasion from Qi. During the Han dynasty, Guangling was the seat of Guangling Commandery. It constituted a part of the Xu Province, rather than the Yang Province (Yangzhou), which was covered the entire southeastern part of China then. In 590, the city was made the capital of a newly established Yang Prefecture, and began to be referred to with its current name.

Under Emperor Yang of Sui (r. 604–617), Yangzhou was the southern capital of China. It was called Jiangdu upon the completion of the Grand Canal until the fall of the Sui dynasty. By the mid 610s, a combination of fruitless attempts to conquer the Korean kingdom of Goguryeo, together with natural disasters and provincial unrest, ensured many people Emperor Yang had lost the legitimacy of his monarchy. As revolts spread across China in 616, the Emperor abandoned the North and meanwhile withdrew to Jiangdu, where he remained until his assassination in 618.

Tang Dynasty

The city has remained a leading economic and cultural center and major port of foreign trade and external exchange since the Tang dynasty (618–907). Many Arab and Persian merchants lived in the city in the 7th century, but they were massacred in the thousands in 760 during the An Lushan Rebellion by Tian Shengong's (Chinese: 田神功; pinyin: Tián Shéngōng; Wade–Giles: T'ien Shen-kung) rebel insurgents during the Yangzhou massacre (760).[6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16]

During the Tang dynasty, many merchants from Silla also lived in Yangzhou.

The city, still known as Guangling, was briefly made the capital of Wu during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period.

From Song to Ming

Yangzhou was briefly the temporary seat of the Song dynasty government between 1128 and 1129,[17] when most of North China had been conquered by the Jurchens during the Jin–Song Wars.[18] The Song had retreated south to the city from their original capital in Kaifeng after it was captured by the Jurchen in the Jingkang Incident of 1127.

From Yangzhou, the Song moved to Hangzhou in 1129, later establishing it as the capital of the Southern Song.[17][19]

In 1280, Yangzhou was the site of a massive gunpowder explosion when the bomb store of the Weiyang arsenal accidentally caught fire. This blast killed over a hundred guards, hurled debris from buildings into the air that landed ten li away from the site of the explosion, and could be felt 100 li away as tiles on roofs shook (refer to gunpowder article).

Marco Polo claimed to have served the Yuan dynasty in Yangzhou under Kubilai Khan in the period around 1282–1287 (to 1285, according to Perkins[6]). Although some versions of Polo's memoirs imply that he was the governor of Yangzhou, it is more likely that he was an official in the salt industry, if indeed he was employed there at all. Chinese texts offer no supporting evidence for his claim. The discovery of the 1342 tomb of Katarina Vilioni, member of an Italian trading family in Yangzhou, does, however, suggest the existence of a thriving Italian community in the city in the 14th century. Moreover, both in The Travels of Marco Polo and in the History of Yuan there is documentation about a Nestorian Christian, who funded two churches in China during the three years he served as an official of the emperor: this functionary is named "Mar Sarchis" by Marco Polo and "Ma Xuelijisi" in the History of Yuan. He served as a supervisor in the province of Zhenjiang, a region neighboring Yangzou.[20] In fact, it is well-documented that Kublai Khan trusted foreigners more than Chinese subjects in internal affairs.[20]

There were also Arabic inscriptions from the 13th and 14th centuries, indicating the presence of a Muslim community.[21]

During the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) until the 19th century Yangzhou acted as a major trade exchange center for salt (a government regulated commodity), rice, and silk. The Ming were largely responsible for building the city as it now stands and surrounding it with 9 km (5.6 mi) of walls.

Early Qing

After the fall of Beijing and northern China to the Manchus in 1644, Yangzhou remained under the control of the short-lived Southern Ming based in Nanjing. Qing forces led by Prince Dodo reached Yangzhou in the spring of 1645, and despite the heroic efforts of its chief defender, Shi Kefa, the city fell on May 20, 1645, after a brief siege. The ten-day Yangzhou massacre followed, Wang alleged that the number of victims was allegedly close to 800,000, that number is now disproven and considered by modern historians and researchers to be a ridiculous exaggeration.[22][23] Shi Kefa himself was killed by the Manchus when he refused to switch his allegiance to the Qing regime.[24]

The city's rapid recovery from these events and its great prosperity through the early and middle years of the Qing dynasty were due to its role as administrative center of the Lianghuai sector of the government salt monopoly. As early as 1655, the Dutch envoy Johan Nieuhof described the city (Jamcefu, i.e. Yangzhou-Fu, in his transcription) commented on the city's salt trade as follows:[25]

This Trade alone has so very much enrich'd the Inhabitants of this Town, that they have re-built their City since the last destruction by the Tartars, erecting it in as great splendor as it was at first.

Famed at that time and since for literature, art, and the gardens of its merchant families, many of which were visited by the Kangxi and Qianling emperors during their Southern Tours, the Qing-era Yangzhou has been the focus of intensive research by historians.

Late Qing and Republican era

The Yangzhou riot in 1868 was a pivotal moment of Anglo-Chinese relations during late Qing China that almost led to war.[26] The crisis was fomented by the scholar-officials of the city, who opposed the presence of foreign Christian missionaries there. The riot that resulted was an angry crowd estimated at eight to ten thousand who assaulted the premises of the British China Inland Mission in Yangzhou by looting, burning and attacking the missionaries led by Hudson Taylor. No one was killed, however several of the missionaries were injured as they were forced to flee for their lives. As a result of the report of the riot, the British consul in Shanghai, Sir Walter Henry Medhurst took seventy Royal Marines in a man-of-war and steamed up the Yangtze to Nanjing in a controversial show of force that eventually resulted in an official apology from Viceroy Zeng Guofan and financial restitution made to the injured missionaries.

From the time of the Taiping Rebellion (1853) to the beginning of the Reform Era (1980) Yangzhou was in decline, due to war damage, neglect of the Grand Canal as railways replaced it in importance, and stagnation in the early decades of the PRC. During the Second Sino-Japanese War, it endured eight years of enemy occupation and was used by the Japanese as a site for internment camps. About 1200 civilians of Allied nationalities (mostly British and Australian) from Shanghai were transported here in 1943, and located in one of three camps (A, B, and C). Camps B and C were closed down in September, 1943, after the second American-Japanese prisoner exchange, and their inhabitants transferred back to Shanghai camps. Camp C, located in the former American Mission in the north-west of the city, was maintained for the duration of the war.[27]

Among early plans for railways in the late Qing was one for a line that would connect Yangzhou to the north but this was jettisoned in favour of an alternative route. The city's status as a leading economic centre in China was never to be restored. Not until the 1990s did it begin to regain some semblance of prosperity, benefitting from national economic growth and a number of targeted development projects. With the canal now partially restored, and excellent rail and road connections, Yangzhou is once again an important transportation and market center. It also has some industrial output, chiefly in cotton and textiles. In 2004, a railway linked Yangzhou for the first time with Nanjing.

Geography

Yangzhou is located on a plain north of the Yangtze. The Grand Canal, also known as the Jing-Hang Canal, crosses the prefecture-level from the north to the south; its modern route passes through the eastern outskirts of Yangzhou's main urban area, while its old route runs through the city center. Other major bodies of water within the prefecture-level city include the Baoshe River, Datong River, Beichengzi River, Tongyang Canal, Xintongyang Canal, Baima Lake, Baoying Lake, Gaoyou Lake and Shaobo Lake.

Like much of the entire prefecture-level city, Yangzhou's main urban area (the "city proper") is criss-crossed by an intricate network of canals and small lakes. The historic city center (the former waled city) is surrounded by canals on all sides: the Old Grand Canal forms its eastern and southern boundaries; the City Moat Canal runs along the former walled city's northern edge, connecting the Old Grand Canal with the Slender West Lake; the Erdaohe Canal runs along the old city's western edge, from the Slender West Lake to the Lotus Flower Pond (Hehuachi), which in its turn is connected by the short Erdaogou canal with the Old Grand Canal.[28] It is possible to sail a small water craft from the Thin West Lake, via the Erdaohe, the Hehua Pond, and the Erdaogou into the Old Grand Canal.[29]

Climate

Yangzhou has a subtropical monsoon climate with humid changeable wind; longer winters for about 4 months, summers 3 months and shorter springs and autumns, 2 months respectively; frost-free period of 222 days and annual average sunshine of 2177 hours.

The mean annual temperature is 15.72 °C (60.3 °F) annually; the normal monthly mean 24-hour temperature ranges from 2.5 °C (36.5 °F) in January to 28.0 °C (82.4 °F) in July.

The annual average precipitation is 1,043 mm (41.1 in), and about 45 percent of rainfall is concentrated in the summer. The rainy season known as "plum rain season" usually lasts from mid-June to late July. During this season, the plums are ripening, hence the name plum rain.

| Climate data for Yangzhou (1981–2010 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.8 (44.2) |

8.9 (48.0) |

13.7 (56.7) |

20.2 (68.4) |

25.9 (78.6) |

28.8 (83.8) |

31.9 (89.4) |

31.3 (88.3) |

27.4 (81.3) |

22.3 (72.1) |

15.9 (60.6) |

9.5 (49.1) |

20.2 (68.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.5 (36.5) |

4.6 (40.3) |

9.0 (48.2) |

15.2 (59.4) |

20.9 (69.6) |

24.6 (76.3) |

28.0 (82.4) |

27.4 (81.3) |

23.2 (73.8) |

17.6 (63.7) |

10.9 (51.6) |

4.7 (40.5) |

15.7 (60.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −0.8 (30.6) |

1.2 (34.2) |

5.2 (41.4) |

10.8 (51.4) |

16.5 (61.7) |

20.9 (69.6) |

24.8 (76.6) |

24.3 (75.7) |

19.8 (67.6) |

13.6 (56.5) |

6.8 (44.2) |

1.0 (33.8) |

12.0 (53.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 45.1 (1.78) |

47.8 (1.88) |

74.8 (2.94) |

71.4 (2.81) |

82.9 (3.26) |

138.1 (5.44) |

207.4 (8.17) |

141.3 (5.56) |

87.8 (3.46) |

56.3 (2.22) |

60.2 (2.37) |

30.3 (1.19) |

1,043.4 (41.08) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 74 | 73 | 71 | 70 | 71 | 76 | 80 | 81 | 78 | 75 | 76 | 73 | 75 |

| Source: China Meteorological Administration[30] | |||||||||||||

Transportation

Yangzhou has one Yangtze River crossing, the Runyang Yangtze River Bridge complex, which has one of the one of the longest suspension bridge spans in the world, and carries the G4011 Yangzhou–Liyang Expressway to Zhenjiang.

Air

The Yangzhou Taizhou International Airport, completed in 2012 to serve Yangzhou and neighbouring Taizhou, is located in Jiangdu district. The Nanjing Lukou International Airport is over 100 km (62 mi) away; it takes one hour and 40 minutes to get there from central Yangzhou. Prior to the completion of the Yangzhou Taizhou Airport, Lukou Airport in Nanjing was the primary air gateway for passengers destined for Yangzhou. There are over 10 airline ticket offices in Yangzhou, providing convenient service for foreign and domestic tourists. domestic and international fight are available with 10 international airlines and more than 20 domestic ones

Rail

Until 2004, Yangzhou was not served by passenger rail. Yangzhou Railway Station began construction in 2003 and was completed a year later. It is located on the western outskirts of the city, and is a major station on the Nanjing–Qidong Railway, and provides direct passenger service to the provincial capital as well as a number of major cities to the west, north, and south (such as Xi'an, Wuhan, and Guangzhou), including an overnight Z-series express train to Beijing.[31] Later, frequent high-speed (D-series) service has been introduced on this line as well.

There is no direct rail service between Yangzhou and Shanghai, however; to travel to Shanghai, or elsewhere in the Yangtze Delta regions, travelers cross the Yangtze over the new Runyang Bridge to Zhenjiang (frequent commuter bus service is available) and take a train from the Zhenjiang Railway Station, which is located on the main Nanjing-Shanghai rail line.

In 2016, construction work started on a new north-south rail line, the Lianyungan-Huai'an-Yangzhou-Zhenjiang Railway. The new Yangzhou station will be located on the east side on the city, between Yangzhou main urban area and Jiangdu District, 16.5 km (10.3 mi) east of the existing Yangzhou Railway Station.[32] The new rail line is expected to open in 2020, while the new train station will gradually become the ciy's transportation hub, and its surrounding area, Yangzhou's new central business district.[32]

River transport

Yangzhou harbour, 11.5 km (7.1 mi) south from the city center, is located at the junction of the Beijing–Hangzhou Canal and the Yangtze River. The average water depth is 15–20 meters. In 1992, the State Council approved it to become a first-grade open state harbour, and General Secretary Jiang Zemin inscribed its name. Now, it has developed into a comprehensive inland harbor, integrating passenger, freight, container transportation and harbour trade, and has become the main distribution center of northern Jiangsu province, eastern Anhui Province and southeast Shandong Province. There are several dozen categories of goods including iron and steel, timber, minerals, coal, grain, cotton, container, products of light industry and machinery. The passenger routes reach Nanjing, Wuhu, Jiujiang, Huangshi and Wuhan in the west, and Nantong and Shanghai in the east. Some well-known luxury international liners also anchor here. The harbour has greatly promoted the development of exports and the overall local economy.

Expressways

The Ningyang (Nanjing–Yangzhou) Expressway crosses the southern part of Yangzhou's metropolitan area while the Ningtong (Nanjing–Nantong) Expressway is connected to Yangzhou at Liaojiagou. In recent years, local government have attached great importance to the development of the tourism, in conjunction with a greater effort dedicated to the improvement of the local road transport system. With a total investment of 680 million yuan, the Yangzhou section of the Ningyang Expressway was completed on December 18, 1998 and opened to traffic in June 1999. Stretching nearly 18 km (11 mi), the section of the expressway starts from the Bazi Flyover as the entry/exit, via the Yanggua Highway, the Tonggang Highway, an ancient canal, the Yangwei Highway, the Beijing–Hangzhou Grand Canal and the Yangling Highway, to Liqojiagou Entry/Exit of Yangjiang Highway. It then passes the Jiangdu Flyover to directly link up with the Huaijiang Expressway. In addition, the section of Huaijiang Expressway within the territory of Yangzhou began construction on March 22, 1997, which will be commonly used by the state planned Tongjiang–Sanya and Beijing–Shanghai trunk lines. The section of Huaijiang Expressway in Yangzhou totals 112.04 km (69.62 mi)in length, starting from Jinghe Town of Baoying in the north to the entry/exist of Zhuanqiaozhen Flyover of Jiangdu in the south. It then links with Ningtong Expressway, passing by three counties (cities) such as Baoying, Gaoyou and Jiangdu and 26 towns, at a total cost of 3.7 billion yuan. It is expected to be open to traffic by the year 2000.

Intercity bus service

During the daytime, frequent bus service operates between Yangzhou and nearby cities. There are several bus stations on the city's outskirts; most of the buses from Nanjing (Nanjing West Bus Station) and Zhenjiang (where the bus station is adjacent to the Zhenjiang Railway Station) arrive to Yangzhou South Bus Station, located a few kilometers southwest from downtown. Most of the intercity bus service stops in the early evening.

Transportation in the Urban Area

The city is served by an extensive network of public bus routes.

Yangzhou's taxi industry began in 1982, and has developed rapidly since 1993. the city has over 40 taxi companies of various ownership structures, with a total of 1,571 vehicles. Parking lots were established at key stations and hotels, and eight taxi companies have opened round-the-clock telephone service. The construction department of the municipal government has strengthened the management of taxi services, providing education in the relevant laws, professional ethics and safety aspects.

In 2014, Yangzhou's government approved plans for the construction of a subway system, which will initially include two lines. Line 1 will run in the general east-west direction, from Yangzhou Railway Station in the west to the historic central city to the future high-speed railway station (east of the Grand Canal) to Jiangdu District. Line 2 will run in the general north-south direction.[33]

Tourist Transportation

To develop tourism in Yangzhou, sightseeing buses have been introduced in the city run by the Tianma travel agency under the Yangzhou Tourist Bureau. There is a tour guide on each bus. The route, starting from Yangzhou station, has eight stops, and passes by such scenic spots of the Slender West Lake, Daming Temple, Imperial Dock, Siwang Pagoda, Wenchang Pagoda and Shita Temple. Yangzhou Public Transit also operates No.1, No.5 and No.2 special tourist lines. No.1 bus departs from the bus station and goes by the Slender West Lake, Shigong Temple, Geyuan Garden and Heyuan Garden; No.5 bus starts from the bus station and goes by the Crane Temple, Wenchang Pagoda, Slender West Lake, Five-Pavilion Bridge, and Pingshan Hall. A sight-seeing route on Slender West Lake has opened, connecting Imperial Dock, Yichun Garden, Hong Garden, Dahong Bridge, Xiaojinshan, Diaoyutai, Five-Pavilion Bridge, and the 24-bridge, finally reaching Daming Temple and Pingshan Hall.[34]

Industries and Shipyards

Yangzhhou is the site of Chengxi shipyard, large shipyard where bulk carriers and other types of large ships are built.[35][36] Owned partly by the state owned CSSC holdings, through Jiangsu Xinrong shipyard, Chengxi Yangzhou shipyard builds ships from 25,000 dwt to 170,000 dwt in size.[37][38][39][40][41]

Cuisine

Yangzhou dishes may be one of the reasons why the people of Yangzhou are so infatuated with their city. They have an appealing color, aroma, taste and appearance. The original color of each ingredient is preserved after cooking, and no oily sauce is added, so as to retain the fresh flavour of the food.

In Yangzhou all dishes, whether cheap or expensive, are elaborate. Cooks will not scrimp on their work, even with dazhu gansi (Chinese: 大煮干丝; pinyin: dàzhǔ gānsī), a popular dish that costs only a few yuan. Dry bean curd is made by each restaurant that serves it, so the flavor is guaranteed. The cook slices the 1-cm-thick curd into 30 shreds, each one paper-thin but none broken, and then stews them for hours with chopped bamboo shoots and shelled shrimps in chicken soup. In this way the dry bean curd shreds can soak up the flavor of the other ingredients, and the soup is clear but savory. Not only Yangzhou cooks, but also the ordinary people are conscientious about cooking.

- Fu Chun Teahouse

- Yangzhou fried rice, is said to have been invented by a person who was a former Yangzhou magistrate.

Culture

The Yangzhou dialect (Chinese: 扬州话; pinyin: Yángzhōu huà) of Chinese is representative of Lower Yangtze Mandarin, and is particularly close to the official language of the Ming and Qing courts, which was based on the Nanjing dialect. However, it does differ considerably from modern Standard Chinese, although they are still moderately mutually intelligible.

Dialect has also been used as a tool for regional identity and politics in the Jiangbei and Jiangnan regions. While the city of Yangzhou was the center of trade, flourishing and prosperous, it was considered part of Jiangnan, which was known to be wealthy, even though Yangzhou was north of the Yangzi river. Once Yangzhou's wealth and prosperity were gone, it was then considered to be part of Jiangbei, the "backwater". After Yangzhou was removed from Jiangnan, its residents decided to replace Jianghuai Mandarin, which was the dialect of Yangzhou, with Taihu Wu dialects. In Jiangnan itself, multiple subdialects of Wu fought for the position of prestige dialect.[42]

During a period of prosperity and Imperial favour, the arts of storytelling and painting flourished in Yangzhou. The innovative painter-calligrapher Shitao lived in Yangzhou during the 1680s and again from 1697 until his death in 1707. A later group of painters from that time called the Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou are famous throughout China.

Former General secretary of CPC, President of China Jiang Zemin was born and raised in Yangzhou. His middle school is located right across from the public notary's office in Yangzhou.

Yangzhou is famous for its carved lacquerware and jade.

Some of China's most creative and eye catching dishes come from the Yangzhou school of cuisine called Huaiyang (also commonly known as the Weiyang school). Along with Sichuan cuisine, Cantonese cuisine, and Shandong cuisine, Huaiyang cuisine (淮扬菜) is a distinctive and masterful skill that locals are quite proud of.

The city is famous for its public bath houses, lacquerware, jadeware, embroidery, paper-cut, art & crafts velvet flavers.

The city was awarded Habitat Scroll of Honour in 2006.

Yangzhou is also very famous for its toy industry (especially stuffed animals). Many tourists from neighboring cities travel to the city for its good-quality and low-priced toys.

It is worth mentioning that the city is also famous for an ancient folk art called Yangzhou storytelling (扬州评话), which is like Xiangsheng—the traditional Chinese comedic performance. It rose as a performing act during the Ming Dynasty. In the performance, the artist details an interesting historical story to audiences, using Yangzhou dialect. These stories have been edited by artists, so they sound very soul-stirring and funny. The best known artist of Yangzhou storytelling was Wang shaotang. His most famous works are The 10 chapters of Wu Song (武十回), The 10 chapters of Song Jiang (宋十回), The 10 chapters of Lu Junyi (卢十回), and The 10 chapters of Shi Xiu (石十回).[43]

Literary references

Yangzhou was frequently referenced in Chinese literature. Poet Li Bai (c.700–762) wrote in Seeing Meng Haoran off to Yangzhou from Yellow Crane Pavilion:

- At Yellow Crane Pavilion in the west

- My old friend says farewell;

- In the mist and flowers of spring

- He goes down to Yangzhou;

- Lonely sail, distant shadow,

- Vanish in blue emptiness;

- All I see is the great river

- Flowing into the far horizon.

Du Mu wrote the famous lines on Yangzhou:[44]

- After ten years, I awoke from my Yangzhou dream,

- All I gained was a fickle reputation in the green mansions.

The "green mansions" or "green/black lofts" (qinglou) refers to the pleasure districts for which Yangzhou became known.[45]

Tourism

Tourist sights include Slender West Lake and old residences in the moated town, such as the Wang Residence and the Daming temple. Yangzhou is famous for its many well preserved Yangzhou style gardens. Most of the Historic city is in the Guangling District.

Slender West Lake

Named after Hangzhou's famous West Lake, this long, narrow stretch of water which meanders through Yangzhou's western limits is a well-known scenic spot. A long bank planted with weeping willows spans the lake; at its midpoint stands a square terrace with pavilions at each of the corners and one in the center. Around the lake is a park in which are found several attractions: Lotus Flower Pagoda (Lianhua SO), a white structure reminiscent of the White Pagoda (Baita) in Beijing's Beihai Park; Small Gold Mountain (Xiao Jin Shan); and the Fishing Platform (Diaoyutai), a favorite retreat of the Qing emperor Qian Long. The emperor was so gratified by his luck in fishing at this spot that he ordered additional stipends for the town. As it turns out, his success had been augmented by local swimmers who lurked in the lake busily attaching fish to his hook.

- Study hall

Four bridges in rain and mist

Four bridges in rain and mist Imperial birthday celebration stage

Imperial birthday celebration stage- Mao Zedong's calligraphy of Tang dynasty poet Du Mu poem

- 24 ancient beauties played flute on this bridge

- Entrance to a garden

- The jinjingge bridge

The Xu Garden

The Xu Garden

Daming Temple

Located on Shugang Hill, in the city's northwest, is Fajing Temple, formerly known as DaMing Temple. The original temple was built in Liu Song Dynasty (420–479). A nine-story pagoda, the Qilingta, was built on the temple grounds in the year of Sui Dynasty (589–618) . A recent addition to the temple complex is the Jianzhen Memorial Hall, built according to Tang Dynasty methods and financed with contributions raised by Buddhist groups in Japan. When Qing Emperor Qian Long visited Yangzhou in 1765, he was troubled by The temple's name DaMing (which literally means "Great Ming') fearing that it might revive nostalgia for the Ming Dynasty, which was overthrown by his Manchu predecessors. He had it renamed Fajing Temple. The temple was seriously damaged during the Taiping Rebellion at the beginning of the 20th century. The present structure is a reconstruction dating from the 1930s.

- Da Ming Temple

Memorial Hall of monk Jianzhen

Memorial Hall of monk Jianzhen Da Ming temple pagoda

Da Ming temple pagoda

Flat Hills (Ping Shan) Hall

Built by the Song Dynasty writer Ouyang Xiu when he served as prefect of the city, this hall stands just west of Fajing Temple. Looking out from this hall, the mountains to the south of the Yangtze River appear as a line at the viewer's eye level, hence the name Flat Hills Hall. When Ouyang Xiu's student Su Dongpo moved to Yangzhou, he too served as prefect of the city. He had a hall built directly behind the one erected by his master, and called it Guling Hall.

Pavilion of Flourishing Culture (文昌阁, Wénchāng Gé)

This round, three-story pavilion in Yangzhou's eastern sector was built in 1585 and celebrates the city's rich cultural traditions. It is also the de facto center of the city.

Built during Ming dynasty, it is located on the cross of Wenchang Road and Wenhe Road. The whole building is about 79-foot high, and looks like Temple of Heaven in Beijing. Today, bordered by many shopping stores, Wenchange had been a symbol of commercial center to residents.

Stone Pagoda

Standing west of the Pavilion of Flourishing Culture is a five-story Tang Dynasty pagoda (Chinese: 石塔; pinyin: Shítǎ). Built in 837, it is the oldest pagoda still standing in Yangzhou.

Tomb of Puhaddin

This is essentially a Ming Dynasty graveyard that includes the tomb of Puhaddin. According to information at the tomb, he was a 16th generation descendant of Muhammad, The Prophet. The tomb is on the eastern bank of the (Old) Grand Canal in the eastern sector of the city and is adjacent to a mosque which houses a collection of valuable materials documenting China's relations with Muslim countries.[46]

Ge Garden (个園, Gè Yuán)

The entrance to this typical southern style garden with its luxuriant bamboo groves, ponds, and rock grottoes is on Dongguan St. in the city's northeast section. Designed by the great Qing Dynasty landscape painter Shi Tao for Wang Yingtai, an officer of the Qing imperial court, this garden takes its name from the shape of bamboo leaves which resemble the Chinese character ge, meaning "a" or "an."

He Garden (何园, Hé Yuán)

This garden, also called Jixiao Shan Zhuang, was built by He Zhidao, a 19th-century Qing government official, this garden home is famous for a 430 m (1,410 ft), two storied winding corridor, the walls of which are lined with stone tablets carved with lines of classical poetry, In the garden is also an open-air theater set on an island in the middle of a fish pond.

Yechun Garden (Yechun Yuan)

In this garden, which lies on the banks of the Xiading River at the city's northern limits, the Qing Dynasty poet Wang Yuyang and a circle of friends used to gather to recite their works. The thatched roofs of the pavilions in this garden give it a quaint, rustic air.

Yangzhou Museum & Yangzhou Block Printing Museum

Situated on the west side of the Bright Moon Lake, the Yangzhou Chinese Block Printing Museum (扬州中国雕版印刷博物馆) and Yangzhou Museum (扬州博物馆) look into the distance of Yangzhou International Exhibition Centre and covers an area of 50,000 square meters, with a construction space of 25,000 square meters, and an exhibition area of 10,000 square metres. Its unique architectural form embodies the harmony of man nature, structure and natural environment. In August, 2003, over 300,000 ancient books blockings were collected from Guangling Press of Yangzhou and China Block Printing Museum was established under the approval of the State Council, over 300,000 ancient book blockings collected by Guangling Press of Yangzhou were included in the new museum.

Jiangdu Hydro Project

Construction of this multiple-purpose water control project, the biggest in China, started in 1961 and was completed in 1975. The project includes facilities for irrigation, drainage, navigation, and power generation. It consists of four large modern electric pumping stations, six medium-sized check gates, thrice navigation locks, and two trunk waterways.

Education

- Yangzhou University

- Sima Primary School

- Yangzhou Polytechnic College

- Yangzhou Polytechnic Institute

Sister cities

.svg.png)

See also

References

- Austin, Alvyn (2007). China’s Millions: The China Inland Mission and Late Qing Society. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2975-7.

- Finnane, Antonia (2004). Speaking of Yangzhou: A Chinese City, 1550 - 1850. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Asia Center. ISBN 0674013921.

- Hay, Jonathan (2001). Shitao: Painting and Modernity in Early Qing China. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39342-6.

- Ho, Ping-ti (1954). "The Salt Merchants of Yang-chou: A Study of Commercial Capital in Eighteenth-Century China,"Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, 17: 130-168.

- Hsü, Ginger Cheng-chi (2001). A Bushel of Pearls: Painting for Sale in Eighteenth-Century Yangchow. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3252-3.

- Meyer-Fong, Tobie (2003). Building Culture in Early Qing Yangzhou. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4485-8.

- Olivová, Lucie, and Vibeke Børdahl (2009). Lifestyle and entertainment in Yangzhou. Copenhagen: NIAS Press. ISBN 978-87-7694-035-5.

- "Yangzhou." Encyclopedia of China. ed. Dorothy Perkins. Chicago: Roundtable Press. 1999. ISBN 1-57958-110-2

- Schinz, Alfred (1996). The magic square: cities in ancient China. Edition Axel Menges. ISBN 3-930698-02-1.

- Yule, Henry (2002), The Travels of Friar Odoric

Notes

- Cox, Wendell (2018). Demographia World Urban Areas. 14th Annual Edition (PDF). St. Louis: Demographia. p. 22.

- "Project documents and reports – Yangzhou thermal power project". projects.worldbank.org/. World Bank. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- "Worldbank report – 1994 – Yangzhou thermal power plant loan" (PDF). World Bank. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- 江苏扬州行政区划调整 江都市改区维扬区被撤销 (in Chinese). China Network Television. 14 November 2011. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

- Schinz, 1996

- Perkins, Dorothy (2000). Encyclopedia of China: The Essential Reference to China, Its History and Culture. Roundtable Press. ISBN 978-0-8160-4374-3.

- Yarshater (1993). William Bayne Fisher; Yarshater, Ilya Gershevitch (eds.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 3 (reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 553. ISBN 0-521-20092-X. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

Probably by the 7th century Persians had joined with Arabs to create the foreign emporium on the Grand Canal at Yangchou mentioned by the New T'ang History. The same source records a disturbance there in 760 in which a thousand of the merchants were killed.

- Jacques Gernet (1996). A history of Chinese civilization (2, illustrated, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 292. ISBN 0-521-49781-7. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

The wealth of the foreign merchants established in the big cities may have provoked the xenophobia that became apparent during rebellions. In 760 several thousand Arab and Persian merchants were massacred at Yangchow by insurgent bands led by T'ien Shen-kung, and a century later, in 879, it was also the foreign merchants who were attacked at Canton under the troops of Huang Ch'ao.

- Tan Ta Sen; Dasheng Chen (2009). Cheng Ho and Islam in Southeast Asia (illustrated, reprint ed.). Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 104. ISBN 981-230-837-7. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

these manliao ( j§ w) [Southern barbarians] would pollute the Chinese culture through intermarriage and upset the land ownership system through land acquisition. . .For example, in AD 760, Yangzhou was attacked by a nearby garrison troop led by Tian Shengong (HJ^ff-w), who was ironically invited by the local authorities to help crush a local uprising. Consequently, a few thousand Arab and Persian merchants were robbed and killed (Jin Tangshu, ch. 110). In the 830s, a mandarin in Guangzhou took steps to control the Arab and Persian Muslims by ordering that Chinese and barbarians must live in separate quarters and must not intermarry; barbarins were also not allowed to own land and paddy fields (Jin Tangshu, ch. 177) Thereafter, Arab and Persian traders lived in designated quarters . . .they also enjoyed religious freedom and kept their Islamic lifestlye intact. . .the Arab and Persian Muslims were also contented to stay out of the Confucian Chinese world so long as the authorities concerned pledged to provide aman [security] for them to lead a peaceful life according to the Islamic doctrines.

- Jacques Gernet (2007). El mundo chino (in Spanish). Editorial Critica. p. 263. ISBN 84-8432-868-6. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

en 760, varios millares de mercaderes árabes y persas fueron masacrados en Yangzhou por bandas insurgentes dirigidas por Tian Shengong; un siglo más tarde las tropas de Huang Chao la emprendieron también en Cantón con los mercaderes extranjeros.

- 新江荣 (1999). 唐研究. Peking University Press. p. 334. ISBN 7-301-04393-7. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

Deng Jingshan fßJSlll , the governor of Yangzhou, ordered general Tian Shengong Ш to lead his forces to suppress the rebels. Shengong entered Yangzhou in 760 and sacked the city, plunderSino-Arab

- 新江荣 (1999). 唐研究. Peking University Press. p. 344. ISBN 7-301-04393-7. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

But, Yangzhou was also a famous trade center with a large foreign community. Chinese sources record several thousand Arabs, Persians, and other foreigner merchants being killed in 760 AD when General Tian Shengong sacked the city during

- Tan Ta Sen; Abdul Kadir; Abdul Kadir. Cheng Ho (in Malay). Penerbit Buku Kompas. p. 143. ISBN 979-709-492-8. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

Misalnya, pada 760, Yangzhou diserang oleh pasukan tentara di bawah pimpinan Tian Shengong (ffltt^d) yang ironisnya diminta oleh penguasa setempat untuk membantu menumpas pemberontakan daerah. Akibatnya, ribuan saudagar Arab dan Persia dirampok dan dibunuh.22 Pada tahun 830-an, seorang pejabat tinggi di Guangzhou mengambil langkah untuk mengawasi orang orang Muslim Arab dan Persian degan memerintahkan orang China dan orang barbar harus tinggal di pemukiman terpisah dan tidak boleh kawin campur; kaum barbar tidak boleh memiliki tanah dan ladang sawah.

- Jacques Gernet (1972). Le monde chinois (in Spanish) (2 ed.). A. Colin. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

milliers de marchands arabes et persans sont massacrés à Yangzhou par les bandes insurgées que mène Tian Shengong; un siècle plus tard, c'est aussi aux marchands étrangers que s'en prennent à Canton les troupes de Huang Chao en 879.

- Jonathan Neaman Lipman (1997). Familiar strangers: a history of Muslims in Northwest China (illustrated ed.). University of Washington Press. p. 27. ISBN 0-295-97644-6. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

They dealt in a vast variety of commodities, and their numbers were not small.9 For example, Tian Shengong's soldiers killed thousands of Dashi and Bosi at Yangzhou in a Tang battle against local rebels. When Huang Chao's rebel army

- Jonathan Neaman Lipman (1997). Familiar strangers: a history of Muslims in Northwest China (illustrated ed.). University of Washington Press. p. 26. ISBN 0-295-97644-6. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

Ouyang, Xin Tang Shu 182.6b--a records the order of Lu Jun, governor of Lingnan at Canton, that foreigners and Chinese could not intermarry (Ch. Fan Hua bu de tong hun), in order to prevent conflict.

- Mote, Frederick W. (2003). Imperial China: 900–1800. Harvard University Press. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-674-01212-7.

- Holcombe, Charles (2011). A History of East Asia: From the Origins of Civilization to the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge University Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-521-51595-5.

- Franke, Herbert (1994). Denis C. Twitchett; Herbert Franke; John King Fairbank (eds.). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 710–1368. Cambridge University Press. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

- Giulio Busi, "Marco Polo. Viaggio ai confini del Medioevo", Collezione Le Scie. Nuova serie, Milano, Mondadori, 2018, ISBN 978-88-0470-292-4, § "Boluo, il funzionario invisibile

- Greville Stewart Parker Freeman-Grenville; Stuart C. Munro-Hay (2006). Islam: an illustrated history (illustrated, revised ed.). Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 228. ISBN 0-8264-1837-6. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- Antonia Finnane (2004). Speaking of Yangzhou: A Chinese City, 1550–1850. Harvard University Asia Center. p. 453. ISBN 978-0674013926.

- 谢国桢,《南明史略》,第72—73页

- "Horrid beyond description": The massacre of Yangzhou", in Voices from the Ming-Qing Cataclysm: China in Tigers' Jaws, ed. Struve, Lynn A. ale University Press, 1998, ISBN 0-300-07553-7. Pages 28–48.

- Johan Nieuhof, An embassy from the East-India Company of the United Provinces, to the Grand Tartar Cham, emperor of China: delivered by their excellencies Peter de Goyer and Jacob de Keyzer, at his imperial city of Peking wherein the cities, towns, villages, ports, rivers, &c. in their passages from Canton to Peking are ingeniously described by John Nieuhoff; ... Englished and set forth with their several sculptures by John Ogilby, 1673, p.82

- Austin (2007), p. 129

- Leck, Greg, Captives of Empire: The Japanese Internment of Allied Civilians in China Shandy Press, 2006; Antonia Finnane, Far From Where? Jewish Journeys from Shanghai to Australia (Melbourne University Press, 1999), 106–7.

- 古运河—荷花池—瘦西湖水上游览线全部贯通]. yztm.net. 2010-09-20.

- 绿杨城郭水上游4·18亮相. yzcn.net. 2011-03-29.; see the map in this article

- 中国气象数据网 – WeatherBk Data (in Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- tielu.org, schedule search for Yangzhou

- 连淮扬镇铁路扬州站场开建 扬州去北京仅4.5小时 [Construction work starts at the site of the Yangzhou station of the Lianyungan-Huai'an-Yangzhou-Zhenjiang Railway. Just 4.5 hours from Yangzhou to Beijing]. 2016-12-25.

- 扬州地 1、2号线走向初定. 扬州网. 2014-06-06.

- "CSSC Official website". cssc.net.cn. CSSC. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- "Shipyards in Jiangsu China". shipyards.gr. Shipyard directory. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- "Chengxi Xinrong shipyard". shipyards.gr. Shipyard directory. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- "Jiangsu Chengxi shipyard". cccme.org.cn. Official website CCCME. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- "Chengxi shipyard Jiangsu". ecmarine.com. East coast marine alliance. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- "China's white listed shipyards". Trade Winds. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- "Our expereince". tymvios.digital. Shulte marine concepts. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- Dorothy Ko (1994). Teachers of the inner chambers: women and culture in seventeenth-century China (illustrated, annotated ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 21. ISBN 0-8047-2359-1. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

With the exclusion of Yangzhou came the denigration of its dialect, a variant of Jianghuai "Mandarin" (guanhua). The various Wu dialects from the Lake Tai area became the spoken language of choice, to the point of replacing guanhua...

- Vibeke Børdahl, The Oral Tradition of Yangzhou Storytelling, London: Routledge, 1996; Vibeke Børdahl and Jette Ross, Chinese Storytellers: Life and Art in the Yangzhou Tradition, Cheng and Tsui 2002.

- Zong-qi Cai (30 November 2007). How to Read Chinese Poetry: A Guided Anthology. p. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231511889.

- Lucie B. Olivová; Vibeke Børdah (1 October 2009). "Lifestyle and Entertainment in Yangzhou". NIAS Press. pp. 287–288. ISBN 978-8776940355.

- "Garden Tomb of Puhaddin Beijing to Shanghai Review". fodors.com.

- "Yangzhou, China". City of Kent, Washington. Archived from the original on 2014-05-20.

- "Yangzhou, China – sister city". Neubrandenburg, Germany website.

- "Offenbach und seine Partnerstädte". City of Offenbach. 21 April 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- "About Sister Cities". Sister Cities New Zealand.

- "Sister Cities Committee". Westport, Connecticut.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yangzhou. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Yangzhou. |