Xavier Mertz

Xavier Guillaume Mertz (6 October 1882 – 8 January 1913) was a Swiss polar explorer, mountaineer, and skier who took part in the Far Eastern Party, a 1912–1913 component of the Australasian Antarctic expedition, which claimed his life. Mertz Glacier on the George V Coast in East Antarctica is named after him.

Xavier Mertz | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Mertz at the expedition's main hut, 1912 | |

| Born | Xavier Guillaume Mertz 6 October 1882 Basel, Switzerland |

| Died | 8 January 1913 (aged 30) George V Land, Antarctica |

| Cause of death |

|

| Education |

|

| Occupation | Polar explorer, mountaineer, skier |

| Known for |

|

| Signature | |

While a student, Mertz became active as a skier, competing in national competitions, and as a mountaineer, climbing many of the highest peaks in the Alps. In early 1911, Mertz was hired by geologist and explorer Douglas Mawson for his Antarctic expedition. He was initially employed as a ski instructor, but in Antarctica, Mertz instead joined Belgrave Edward Ninnis in the care of the expedition's Greenland huskies.

In the summer of 1912–1913, Mertz and Ninnis were chosen by Mawson to accompany him on the Far Eastern Party, using the dogs to push rapidly from the expedition's base in Adélie Land towards Victoria Land. After Ninnis and a sledge carrying most of the food disappeared down a crevasse, 311 miles (500 km) from the expedition's main hut, Mertz and Mawson headed back west, gradually using the dogs to supplement their remaining food stocks.

About 100 miles (160 km) from safety, Mertz died, leaving Mawson to carry on alone. The cause of Mertz's death has never been firmly established; the commonly purported theory is hypervitaminosis A—an excessive intake of vitamin A—from consuming the livers of the Huskies. Other theories suggest he may have died from a combination of malnutrition, cold exposure, and psychological stresses.

Early life

Xavier Mertz was born in Basel, the son of Emile Mertz, who owned a large engineering firm in the city. With the aim of working in the family business, which manufactured textile machinery, Mertz attended the University of Bern, where he studied patent law.[1][2]

While in Bern, he became active as a mountaineer and skier.[2] Mertz competed in several national competitions; in 1906 he was third in the Swiss cross-country skiing championship, and second in the German championship.[3] In 1908, he won the Swiss ski jumping championship, with a distance of 31 metres (102 ft).[4] As a mountaineer, he was particularly prolific in the Alps; he climbed Mont Blanc—the highest peak in the range—and claimed several first ascents of other mountains.[5]

After he attained his degree of Doctor of Laws from the University of Bern, Mertz studied science at the University of Lausanne; he specialised in glacier and mountain formations, for which he received his second doctorate.[nb 1][1]

Australasian Antarctic expedition

In early 1911, Mertz went to London to meet with the Australian geologist and explorer Douglas Mawson.[2] Mawson, who had served as physicist during Ernest Shackleton's 1908–1909 Nimrod expedition, was planning his own Antarctic expedition.[7]

In his application letter, Mertz wrote that he hoped Mawson would be using skis, as "they have proved so good for the purpose & knowing that I am as good as any one on skys."[5] While Mawson was intending to recruit only British subjects (chiefly Australians and New Zealanders), Mertz's qualifications prompted him to make an exception, and hire the Swiss as a ski instructor.[5] First, however, he was given responsibility for the expedition's 48 dogs, aboard the expedition ship SY Aurora, bound for Hobart.[8]

On the Aurora, Mertz met Belgrave Edward Sutton Ninnis, a lieutenant in the Royal Fusiliers. Like Mertz, Ninnis was responsible for the expedition's dogs; Aurora's captain, John King Davis, regarded the pair as "idlers". "I wish we had some one on board who could look after [the dogs]," he wrote in his diary, "it is a great shame that they should suffer from neglect."[9] On 2 December 1911, after final preparations and loading were completed in Hobart, the Aurora sailed south;[10] she stopped briefly at Macquarie Island, where a wireless relay base was established, and reached the site of the expedition's main base at Cape Denison in Adélie Land, on the Antarctic continent, in early January.[11][12]

Adélie Land

Over the following winter, preparations were made for the summer sledging. Because the conditions—constant, strong winds and an excessive slope by the hut—prevented Mertz from conducting skiing lessons as regularly as intended, he focussed instead on helping Ninnis to care for the dogs.[13] On days when the weather was good they drove the dogs around outside the hut, teaching them to run in teams; when the winds returned the pair fitted and sewed harnesses for each dog, and prepared their sledging food.[14] By this time Mertz and Ninnis developed a close friendship, as the expedition's taxidermist Charles Laseron later wrote:

The two [Mertz and Ninnis] had joined the Expedition together in London, and had been associated longer and in a more intimate manner than any other members of the Expedition. During the winter months we had all been drawn together, but between Mertz and Ninnis there existed a very deep bond. Mertz, in his warm-hearted impulsive way, had practically adopted Ninnis, and his affection was almost maternal. Ninnis, less demonstrative, reciprocated this to the full, and indeed it was hard to dissociate them in our thoughts. It was always 'Mertz and Ninnis' or 'Ninnis and Mertz', a composite entity, each the complement of the other.[15]

In August, the preparations extended to laying depots; an early party established a depot 5.5 miles (8.9 km) to the south of the expedition's main hut—a grotto in the ice known as Aladdin's Cave—but returned without the dogs. Mertz and two others set off to rescue the dogs, but in heavy winds covered less than a mile in two hours, and returned to the hut. "If it depended only on me," Mertz wrote in his diary, after four days' more wind confined them to the hut, "we would be in our sleeping bags outside in the snow, and we would at least try to find the dogs. Mawson is definitely too cautious, and I wonder if he would show enough gumption during the sledging expedition."[16] The following day Mertz was part of a party of three that made it to Aladdin's Cave to rescue the dogs; when strong winds confined them to the depot for three days they spent the time expanding the cave.[17]

In September, Mertz, Ninnis, and Herbert Murphy formed a survey party, man-hauling to the south-east of Aladdin's cave. In strong winds, they travelled just 12.5 miles (20 km) in three days, before the temperature dropped to −34 °C (−29 °F) and the wind speed increased to 90 miles per hour (78 kn), confining them to the tent. When a gap in the wind allowed, they hurried back to the hut.[18]

Far Eastern Party

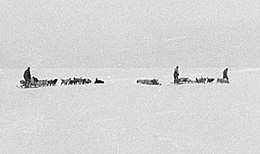

On 27 October 1912, Mawson outlined the summer sledging program.[19] Mertz and Ninnis were assigned to Mawson's own party, which would use the dogs to push quickly to the east of the expedition's base in Commonwealth Bay, towards Victoria Land.[20] The party departed Cape Denison on 10 November, heading first to Aladdin's Cave, and from there south-east towards a massive glacier encountered by Aurora on the outward journey.[21] Mertz skied ahead, scouting and providing a lead for the dogs to chase; Mawson and Ninnis manoeuvred the two dog teams behind.[22] They reached the glacier on 19 November; negotiating fields of crevasses, it was crossed in five days.[23][24] The party made quick progress once on the plateau again, but they soon encountered another glacier, far larger than the first. Despite strong winds and poor light, Mertz, Mawson and Ninnis reached the far side on 30 November.[25]

On 14 December, the party were more than 311 miles (501 km) from the Cape Denison hut. As Mertz skied ahead, singing songs from his student days, Ninnis, the largest sledge and the strongest dog team were lost when they broke through the snow lid of a crevasse.[26][27] Together with the death of their companion, Mawson and Mertz were now severely compromised; on the remaining sledge they had just ten days' worth of food, and no food for the dogs.[28] They immediately turned back west, gradually using the six remaining dogs to supplement their food supply; they ate all parts of the animals, including their livers.[29]

They initially made good progress, but as they cleared the largest glacier Mertz began to feel ill; he had lost his waterproof overpants on Ninnis' sledge, and in the cold his wet clothes were unable to dry.[30] On 30 December, a day Mawson recorded that the companion was "off colour", Mertz wrote that he was "really tired [and] shall write no more."[nb 2] Mertz's condition deteriorated over the following days—Mawson recorded he was "generally in a very bad condition. Skin coming off legs, etc"—and his illness severely slowed their progress.[32] On 8 January, the pair about 100 miles (160 km) from the hut, Mawson recorded:

He [Mertz] is very weak, becomes more and more delirious, rarely being able to speak coherently. He will eat or drink nothing. At 8 pm he raves & breaks a tent pole. Continues to rave & call 'Oh Veh, Oh Veh' [O weh!, 'Oh dear!'] for hours. I hold him down, then he becomes more peaceful & I put him quietly in the bag. He dies peacefully at about 2 am on morning of 8th.[33][34]

Mawson buried Mertz in his sleeping bag under rough-hewn blocks of snow, along with the remaining photographic plates and an explanatory note.[35] Mawson staggered back into the Cape Denison hut a month later, missing the Aurora by a matter of hours; she had waited for Mertz, Mawson and Ninnis for three weeks until—concerned by the encroaching winter ice—Davis had sailed her out of Commonwealth Bay and back to Australia.[36][37]

Legacy

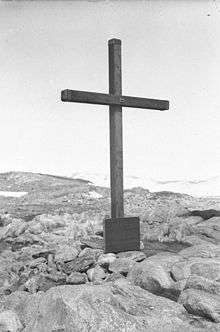

In November 1913, a month before the Aurora returned for the final time, Mawson and the six men remaining at Cape Denison erected a memorial cross for Mertz and Ninnis on Azimuth Hill to the north-west of the main hut.[38] The cross, constructed from pieces of a broken radio mast, was accompanied by a plaque cut from wood from Mertz's bunk.[39] The cross still stands, although the crossbar has required reattaching several times, and the plaque was replaced with a replica in 1986.[40]

The first glacier the Far Eastern Party crossed on the outward journey—previously unnamed—was named by Mawson after Mertz, becoming the Mertz Glacier.[41] At a speaking engagement upon his return to Australia, Mawson praised his dead comrades: "The survivors might have an opportunity of doing something more, but these men had done their all."[42] At another, Mawson said that "Dr. Mertz was a Swiss by birth, but he was a man every Englishman would have liked to have called an Englishman ... He was a man of great feelings, generous—one of Nature's gentlemen."[43] A telegram was sent on behalf of the Australian people to Emile Mertz, condoling him on his "great loss, but congratulating you on your son's imperishable fame."[44]

The cause of Mertz's death is not certain; at the time, it was believed Mertz may have died of colitis.[45] A 1969 study by Sir John Cleland and Ronald Vernon Southcott, of the University of Adelaide, concluded that the symptoms Mawson described—hair, skin and weight loss, depression, dysentery and persistent skin infections—indicated the men had suffered hypervitaminosis A, an excessive intake of vitamin A. Vitamin A is found in unusually high quantities in the livers of Greenland huskies, of which both Mertz and Mawson consumed large amounts;[45] indeed, as Mertz's condition deteriorated, Mawson may have given him more of the liver to eat, believing it to be more easily digested.[46]

This theory is the most widely accepted, but there have been other theories.[47] Phillip Law, former director of Australian National Antarctic Research Expeditions, believed cold exposure could account for Mertz's symptoms.[48] A 2005 article in The Medical Journal of Australia by Denise Carrington-Smith, noting certain sources indicating that Mertz was essentially a vegetarian, suggested that general malnutrition and the sudden change to a predominantly meat diet could have triggered Mertz's illness. Carrington-Smith adds a more hypothetical reason: "the psychological stresses related to the death of a close friend [Ninnis] and the deaths of the dogs he had cared for, as well as the need to kill and eat his remaining dogs".[49]

See also

References

Notes

- Mertz's biography in the official account of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition, The Home of the Blizzard, records that he also studied law at the University of Leipzig.[6]

- Mertz's last entry in his diary was on 1 January, a week before his death. After he died, Mawson tore the remaining blank pages from the diary to save weight.[31]

Footnotes

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 11 July 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- "Dr. Xavier Mertz: how he joined the expedition", The Hobart Mercury, National Library of Australia: 5, 27 February 1913

- "Concerning people", The South Australian Register, National Library of Australia: 8, 14 May 1914

- Ayres 2000, p. 56.

- Riffenburgh 2009, p. 46.

- Mawson 1915, p. 287.

- Jacka, Fred (1986). Mawson, Sir Douglas (1882–1958). Australian Dictionary of Biography. Australian National University. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- Ayres 2000, p. 53.

- Ayres 2000, pp. 56–57.

- Ayres 2000, pp. 57–58.

- Bickel 2000, pp. 37–38.

- Ayres 2000, p. 63.

- Riffenburgh 2009, pp. 80–81.

- Bickel 2000, pp. 67, 77.

- Laseron 1947, pp. 212–213.

- Riffenburgh 2009, pp. 91–92.

- Riffenburgh 2009, p. 92.

- Riffenburgh 2009, p. 94.

- Riffenburgh 2009, p. 98.

- Bickel 2000, pp. 78–79.

- Riffenburgh 2009, pp. 103–104.

- Riffenburgh 2009, p. 107.

- Riffenburgh 2009, p. 108.

- Mawson 1915, p. 230.

- Riffenburgh 2009, pp. 110–112.

- Hayes 1936, p. 163.

- Ayres 2000, pp. 72–73.

- Hall 2000, p. 126.

- Ayres 2000, pp. 74–76.

- Riffenburgh 2009, pp. 126–127.

- Ayres 2000, p. 76.

- Mawson 1988, p. 156.

- Mawson 1988, p. 158.

- Ayres 2000, p. 77.

- Riffenburgh 2009, p. 131.

- Hall 2000, pp. 138–139.

- Ayres 2000, pp. 86–87.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 20 August 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Bickel 2000, p. 254.

- "History". Mawson's Huts Foundation. Australian Antarctic Division. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- "Mertz Glacier". Australian Antarctic Data Centre. Australian Antarctic Division. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- "Dr. Mawson's Reply", The Advertiser, National Library of Australia: 16, 4 March 1914

- "Nature's Gentlemen", The South Australian Register, National Library of Australia: 10, 3 March 1914

- "The Cable of Sympathy", The Advertiser, National Library of Australia: 16, 4 March 1914

- Riffenburgh 2009, p. 136.

- Bickel 2000, p. 260.

- Riffenburgh 2009, p. 137.

- Ayres 2000, pp. 80–81.

- Carrington-Smith 2005, p. 641.

Bibliography

- Ayres, P. J. (2000). Mawson: a life. Melbourne University Press. ISBN 9780522848113.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bickel, L. (2000). Mawson's Will: the greatest polar survival story ever written. South Royalton: Steerford. ISBN 9781586420000.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carrington-Smith, D. (2005). "Mawson and Mertz: a re-evaluation of their ill-fated mapping journey". Med. J. Aust. 183 (11): 638–641. PMID 16336159.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hall, L.; et al. (2000). Douglas Mawson: the life of an explorer. Sydney: New Holland. ISBN 9781864366709.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hayes, J. G. (1936). The conquest of the South Pole: Antarctic exploration, 1906–1931. London: T. Butterworth. OCLC 38702053.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Laseron, C. F. (1947). South with Mawson: reminiscences of the Australasian Antarctic expedition. Sydney: Harrap & Co. OCLC 1065222652.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mawson, D. (1915). The home of the blizzard: the story of the Australasian Antarctic expedition. London: Heinemann. OCLC 502644949.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mawson, D. (1988). Jacka, F.; et al. (eds.). Mawson's Antarctic diaries. North Sydney: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 9780043202098.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Riffenburgh, B. (2009). Racing with death: Douglas Mawson, Antarctic explorer. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9780747596714.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Xavier Guillaume Mertz. |

- Works by or about Xavier Mertz at Internet Archive

- Works by or about Xavier Mertz in libraries (WorldCat catalog)