Willard InterContinental Washington

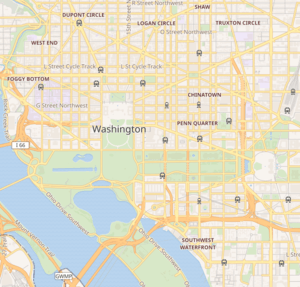

The Willard InterContinental Washington, commonly known as the Willard Hotel, is a historic luxury Beaux-Arts[3] hotel located at 1401 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C. Among its facilities are numerous luxurious guest rooms, several restaurants, the famed Round Robin Bar, the Peacock Alley series of luxury shops, and voluminous function rooms.[4] Owned by InterContinental Hotels & Resorts, it is two blocks east of the White House, and two blocks west of the Metro Center station of the Washington Metro.

Willard Hotel | |

| |

| Location | 1401–1409 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, Washington, D.C., U.S. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 38°53′47.22″N 77°1′56.46″W |

| Built | Original six structures: 1816[1] Unified structure: 1847[2] Current structure: 1901[3] |

| Architect | Henry Janeway Hardenbergh (hotel)[3] Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Associates and Vlastimil Koubek, annex |

| Architectural style | Beaux-Arts[3] |

| NRHP reference No. | 74002177 |

| Added to NRHP | February 15, 1974 |

History

The first structures to be built at 1401 Pennsylvania Avenue NW were six small houses constructed by Colonel John Tayloe III in 1816.[1] Tayloe leased the six buildings to Joshua Tennison, who named them Tennison's Hotel.[1][5] The structures served as a hotel for the next three decades, the leaseholder and name changing several times: Williamson's Mansion Hotel, Fullers American House, and the City Hotel.[5] By 1847, the structures were in disrepair and Tayloe's son, Benjamin Ogle Tayloe, was desperate to find a tenant who would maintain the structures and run them profitably.[6]

The Willard Hotel was formally founded by Henry Willard when he leased the six buildings in 1847, combined them into a single structure, and enlarged it into a four-story hotel he renamed the Willard Hotel.[2][6][7] Willard purchased the hotel property from Ogle Tayloe in 1864, but a dispute over the purchase price and the form of payment (paper currency or gold coin) led to a major equity lawsuit which ended up in the Supreme Court of the United States. The Supreme Court split the difference in Willard v. Tayloe. 75 U.S. 557 (1869): The purchase price would remain the same, but Willard must pay in gold coin (which had not depreciated in value the way paper currency had).

The present 12-story structure, designed by famed hotel architect Henry Janeway Hardenbergh, opened in 1901.[3][4] It suffered a major fire in 1922 which caused $250,000 (equivalent to $3,818,588 as of 2019),[8] in damages.[9] Among those who had to be evacuated from the hotel were Vice President Calvin Coolidge, several U.S. senators, composer John Philip Sousa, motion picture producer Adolph Zukor, newspaper publisher Harry Chandler, and numerous other media, corporate, and political leaders who were present for the annual Gridiron Dinner.[9] For many years the Willard was the only hotel from which one could easily visit all of downtown Washington, and consequently it has housed many dignitaries during its history.

The Willard family sold its share of the hotel in 1946, and due to mismanagement and the severe decline of the area, the hotel closed without a prior announcement on July 16, 1968.[10] The building sat vacant for years, and numerous plans were floated for its demolition. It eventually fell into a semi-public receivership and was sold to the Pennsylvania Avenue Development Corporation. They held a competition to rehabilitate the property and ultimately awarded it to the Oliver Carr Company and Golding Associates.[11] The two partners then brought in the InterContinental Hotels Group to be a part owner and operator of the hotel. The Willard was subsequently restored to its turn-of-the-century elegance and an office-building contingent was added. The hotel was thus re-opened amid great celebration on August 20, 1986, which was attended by several U.S. Supreme Court justices and U.S. senators. In the late 1990s, the hotel once again underwent significant restoration.

Notable guests

The first group of three Japanese ambassadors to the United States stayed at the Willard with seventy-four other delegates in 1860, where they observed that their hotel room was more luxurious than the U.S. Secretary of State's house.[12] It was the first time an official Japanese delegation traveled to a foreign destination, and many tourists and journalists gathered to see the sword-carrying Japanese.[13]

In the 1860s, author Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote that "the Willard Hotel more justly could be called the center of Washington than either the Capitol or the White House or the State Department."[14]

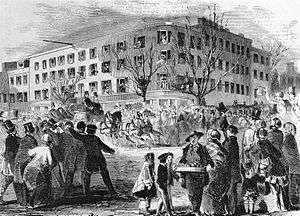

From February 4 to February 27, 1861, the Peace Congress, featuring delegates from 21 of the 34 states, met at the Willard in a last-ditch attempt to avert the Civil War. A plaque from the Virginia Civil War Commission, located on the Pennsylvania Ave. side of the hotel, commemorates this courageous effort. Later that year, upon hearing a Union regiment singing "John Brown's Body" as they marched beneath her window, Julia Ward Howe wrote the lyrics to "The Battle Hymn of the Republic" while staying at the hotel in November 1861.[4]

On February 23, 1861, amid several assassination threats, detective Allan Pinkerton smuggled Abraham Lincoln into the Willard; there Lincoln lived until his inauguration on March 4, holding meetings in the lobby and carrying on business from his room.[15]

On March 27, 1874, the Northern and Southern Orders of Chi Phi met at the Willard to unite as the Chi Phi Fraternity.

Many United States presidents have frequented the Willard, and every president since Franklin Pierce has either slept in or attended an event at the hotel at least once; the hotel hence is also known as "the residence of presidents."[16] It was the habit of Ulysses S. Grant to drink whiskey and smoke a cigar while relaxing in the lobby. Folklore (promoted by the hotel) holds that this is the origin of the term "lobbying," as Grant was often approached by those seeking favors. However, this is probably false, as Webster's Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary dates the verb "to lobby" to 1837. Grover Cleveland lived there at the beginning of his second term in 1893, because of concern for his infant daughter's health following a recent outbreak of scarlet fever in the White House.[17] Plans for Woodrow Wilson's League of Nations took shape when he held meetings of the League to Enforce Peace in the hotel's lobby in 1916. Six sitting Vice-Presidents have lived in the Willard. Millard Fillmore and Thomas A. Hendricks, during his brief time in office, lived in the old Willard; and then four successive Vice-Presidents, James S. Sherman, Thomas R. Marshall, Calvin Coolidge and finally Charles Dawes all lived in the current building for at least part of their vice-presidency. Fillmore and Coolidge continued in the Willard, even after becoming president, to allow the first family time to move out of the White House.

A fire broke out in April 1922 while Calvin Coolidge was staying in the building. Attempting to re-enter the building, he was asked to identify himself to the fire marshal, to which he responded, "I'm the Vice President." The fire marshal's response was "What are you vice president of?"[18]

Several hundred officers, many of them combat veterans of World War I, first gathered with the General of the Armies, John J. "Blackjack" Pershing, at the Willard Hotel on October 2, 1922, and formally established the Reserve Officers Association (ROA) as an organization.[19]

The first recorded meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research was convened at the Willard on May 7, 1907.[20]

In 1935 the hotel was used as a place of confinement for William P. MacCracken Jr., Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Aeronautics, after he was convicted of contempt of Congress in the Air Mail scandal. According to The Washington Post, "Chesley Jurney, the Senate sargeant at arms, had no place to hold MacCracken who, after being sentenced, showed up at Jurney's house and stayed the night. The next day he was confined to a room at the Willard Hotel."[21]

During World War II the British government rented several of the Willard's floors for its supply organization. Jean Monnet had his office there. In 1997 a memorial plaque was erected near the hotel's entrance to commemorate this episode.[22]

Martin Luther King, Jr., wrote his famous "I Have a Dream" speech in his hotel room at the Willard in 1963 in the days before his March on Washington.[4]

On September 23, 1987, it was reported that Bob Fosse collapsed in his room at the Willard and later died. It was subsequently learned that he actually died at George Washington University Hospital.

Among the Willard's many other famous guests are P. T. Barnum, Mark Twain, Walt Whitman, General Tom Thumb, Samuel Morse, the Duke of Windsor, Harry Houdini, Gypsy Rose Lee, Gloria Swanson, Emily Dickinson, Jenny Lind, Charles Dickens, Bert Bell, Joe Paterno, and Jim Sweeney.[23][24]

Steven Spielberg shot the finale of his film Minority Report at the hotel in the summer of 2001. He filmed with Tom Cruise and Max von Sydow in the Willard Room, Peacock Alley and the kitchen. A replica of the terraced roof of the office building was constructed on a soundstage for the final scene.[25]

On February 22, 2012, Australian Foreign Minister Kevin Rudd gave a dramatic resignation speech in the hotel's Douglas Room.[26] Bread and Butter, the turkeys pardoned by US President Donald Trump stayed here prior to the pardoning ceremony.

Rating

The AAA gave the hotel four diamonds out of five in 1986. The hotel has maintained that rating every year, and received four diamonds again for 2016.[27] Forbes Travel Guide (formerly known as Mobil Guide) declined to give the hotel either four or five stars in 2016, but did add it to its list of "recommended" properties.[28]

Gallery

The Willard Office Building, built in 1986 and designed to blend with the historic hotel

The Willard Office Building, built in 1986 and designed to blend with the historic hotel The Washington Monument as viewed from the Willard Hotel by Carol M. Highsmith

The Washington Monument as viewed from the Willard Hotel by Carol M. Highsmith Willard Hotel's menu on February 20, 1861

Willard Hotel's menu on February 20, 1861

Willard Lobby, Christmas 2014

Willard Lobby, Christmas 2014

See also

- List of Historic Hotels of America

- Jim Hewes, bartender at the Willard's Round Robin Bar

References

- Moeller and Weeks, AIA Guide to the Architecture of Washington, D.C., 2006, p. 133.

- Tindall, Standard History of the City of Washington From a Study of the Original Sources, 1914, p. 353–354.

- Denby, Grand Hotels: Reality and Illusion, 2004, p. 221–222.

- Moeller and Weeks, AIA Guide to the Architecture of Washington, D.C., 2006, p. 134.

- Hogarth, Walking Tours of Old Washington and Alexandria, 1985, p. 28.

- Willard, "Henry August Willard: His Life and Times," Records of the Columbia Historical Society, 1917, p. 244–245.

- Burlingame, With Lincoln in the White House, 2006, p. 197.

- Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- "Notables Routed By Top Floor Fire In Willard Hotel," The New York Times, April 24, 1922.

- [https://www.nytimes.com/1968/07/16/archives/historic-willard-hotel-in-capital-is-suddenly-closed-historic.html New York Times, July 16, 1968

- Barbara Gamarekian, "The Willard is Restored as a Jewel of Pennsylvania Avenue", New York Times, 1986-09-04

- Elizabeth Smith Brownstein, The Willard Hotel (PDF), The White House Historical Association, retrieved 2013-03-04

- Dallas Finn. "Guests of the Nation: The Japanese Delegation to the Buchanan White House" (PDF). White House Historical Association. Retrieved 2013-03-04.

- The Willard Hotel, National Park Service, retrieved 2018-07-18

- "Feb 23, 1861: Lincoln avoids assassination attempt". History.com. Retrieved 2013-03-04.

- Greg Pesto. "Hotel Of The Day: Willard InterContinental". Forbes.com. Retrieved 2013-03-04.

- Graff, H. (2002) Grover Cleveland p. 113

- ghostsofdc (2012-04-17). "Calvin Coolidge, The Vice President of What? | Ghosts of DC". Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- "History of ROA". Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- Triolo V; Riegel, IL (1961). "The American Association for Cancer Research, 1907–1940: Historical Review". Cancer Res. 21 (2): 137–167. PMID 13778091.

- Philip Bump (January 18, 2018) Congress’s ability to twist arms is limited, The Washington Post

- Clifford P. Hackett, ed. (1995). Monnet and the Americans: The father of a united Europe and his U.S. supporters. Washington D.C.: Jean Monnet Council. p. 41.

- Louise Sweeney (1986-06-26). "Restoring the Willard. Historic hotel again reflects its glittering past". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2013-03-04.

- "The Willard Hotel". American Heritage Publishing. Retrieved 2013-03-04.

- "The Willard InterContinental, Washington DC". National Trust for Historic Preservation. Retrieved 2013-03-04.

- Norington, Brad (February 22, 2012). "Perfect setting in a Washington hotel for politician's career relaunch". The Australian. Retrieved February 23, 2012.

- American Automobile Association (January 15, 2016). AAA/CAA Four Diamond Hotels (PDF) (Report). p. 1. Retrieved May 3, 2016.

- "Forbes Travel Guide 2016 Star Award Winners". Forbes Travel Guide. February 2016. Retrieved May 3, 2016.

Bibliography

- Burlingame, Michael. With Lincoln in the White House: Letters, Memoranda, and Other Writings of John G. Nicolay, 1860–1865. Carbondale, Ill.: SIU Press, 2006.

- Denby, Elaine. Grand Hotels: Reality and Illusion. London: Reaktion Books, 2004.

- Hogarth, Paul. Walking Tours of Old Washington and Alexandria. McLean, Va.: EPM Publications, 1985.

- Moeller, Gerard Martin and Weeks, Christopher. AIA Guide to the Architecture of Washington, D.C. 4th ed. Baltimore: JHU Press, 2006.

- "Notables Routed By Top Floor Fire In Willard Hotel." New York Times. April 24, 1922.

- Tindall, William. Standard History of the City of Washington From a Study of the Original Sources. Knoxville, Tenn.: H.W. Crew & Co., 1914.

- Willard, Henry Kellogg. "Henry August Willard: His Life and Times." Records of the Columbia Historical Society. 1917.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Willard InterContinental. |

- Willard InterContinental Washington

- NPR interview with Barbara Bahny, public relations director at the historic Willard Hotel

- Willard InterContinental: Sustainable Development Initiative

- View menu of the Willard Hotel from 1861 at the University of Houston Digital Library

- Ghosts of DC blog posts about The Willard Hotel – local D.C. history blog

- SAH Archipedia Building Entry