Vietnam Veterans Memorial

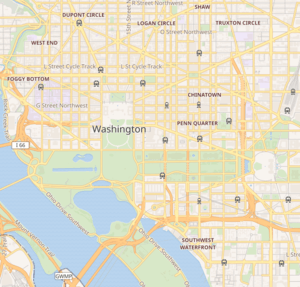

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial is a 2-acre (8,093.71 m²) U.S. national memorial in Washington, D.C. It honors service members of the U.S. armed forces who fought in the Vietnam War, service members who died in service in Vietnam/South East Asia, and those service members who were unaccounted for during the war.

| Vietnam Veterans Memorial | |

|---|---|

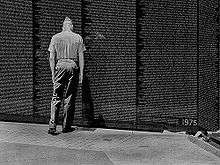

Visitors at the wall in January 2005 | |

| |

| Location | Washington, D.C., United States |

| Coordinates | 38°53′28″N 77°2′52″W |

| Area | 2 acres (0.81 ha) |

| Established | November 13, 1982 |

| Visitors | 3,799,968 (in 2006) |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Vietnam Veterans Memorial |

| Architect | Maya Lin |

| NRHP reference No. | 01000285[1] |

| Added to NRHP | November 13, 1982 |

Its construction and related issues have been the source of controversies, some of which have resulted in additions to the memorial complex. This is reflected in the fact that the Vietnam memorial is now made up of three parts: the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall, completed first and the best-known part of the memorial; The Three Soldiers; and the Vietnam Women's Memorial.

The main part of the memorial, the wall of names, which was completed in 1982, is in Constitution Gardens adjacent to the National Mall, just northeast of the Lincoln Memorial. The memorial is maintained by the National Park Service, and receives around 3 million visitors each year. The Memorial Wall was designed by American architect Maya Lin. In 2007, it was ranked tenth on the "List of America's Favorite Architecture" by the American Institute of Architects. As a National Memorial, it is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Appearance

Memorial Wall

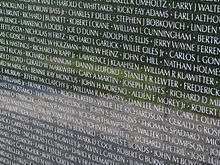

The Memorial Wall is made up of two 246-foot-9-inch (75.21 m) long black granite walls, polished to a high finish, and etched with the names of the servicemen being honored in 140 panels of horizontal rows with regular typeface and spacing.[2][3] The walls are sunken into the ground, with the earth behind them. At the highest tip (the apex where they meet), they are 10.1 feet (3.1 m) high, and they taper to a height of 8 inches (200 mm) at their extremities. Symbolically, this is described as a "wound that is closed and healing" and exemplifies the Land art movement of the 1960s which produced sculptures that sought to reconnect with the natural environment.[4] The stone for the 144 panels was quarried in Bangalore, India.

One wall points toward the Washington Monument, the other in the direction of the Lincoln Memorial, meeting at an angle of 125° 12′. Each wall has 72 panels, 70 listing names (numbered 1E through 70E and 70W through 1W), and two very small blank panels at the extremities. There is a pathway along the base of the Wall where visitors may walk.

The wall originally listed 57,939 names when it was dedicated in 1982;[5] however other names have since been added and as of May 2018 there were 58,320 names, including eight women. The number of names on the wall is different than the official number of U.S. Vietnam War deaths, which is 58,220 as of May 2018.[6] The names inscribed are not a complete list of those who are eligible for inclusion as some names were omitted at the request of families.[7]

Directories containing all of the names are located on nearby podiums at both ends of the monument where visitors may locate specific names.

The memorial has had some unforeseen maintenance issues. In 1984, cracks were detected in the granite and, as a result, two of the panels were temporarily removed in 1986 for study. More cracks were later discovered in 2010. There are a number of hypotheses about the cause of the cracks, the most common being due to thermal cycling. In 1990, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund purchased several blank panels to use in case any were ever damaged; these were placed into storage at Quantico Marine Base.[8][9] Two of the blank panels were shattered by the 2011 Virginia earthquake.[10]

Names

Inscribed in the memorial are the names of service members classified as "declared dead"; as the memorial contains names of individuals who had died due to circumstances other than killed in action, including murder, vehicle accidents, drowning, heart attack, animal attack, snake bites and others.[11] Also included are the names of those whose status is unknown, which typically means "missing in action" (MIA). The names are inscribed in Optima typeface, designed by Hermann Zapf.[4] Information about the rank, unit, and decorations is not given.

Those who are declared dead are denoted by a diamond, and those who are status unknown are denoted with a cross. When the death of one who was previously missing is confirmed, a diamond is superimposed over the cross. If the missing were to return alive, which has never occurred to date, the cross is to be circumscribed by a circle.

The earliest date of eligibility for a name to be included on the memorial is November 1, 1955, which corresponds to President Eisenhower deploying the Military Assistance Advisory Group to train the Army of the Republic of Vietnam. The last date of eligibility is May 15, 1975, which corresponds to the final day of the Mayaguez incident.[12] There are circumstances that allow for a name to be added to the memorial, but the death must be directly attributed to a wound received within the combat zone while on active duty. In such cases, the determination is made by the Department of Defense.[5] In these cases, the name is added according to the date of injury—not the date of death. The names are listed in chronological order, starting at the apex on panel 1E on July 8, 1959, moving day by day to the end of the eastern wall at panel 70E, which ended on May 25, 1968, starting again at panel 70W at the end of the western wall which completes the list for May 25, 1968, and returning to the apex at panel 1W in 1975. There are some deaths that predate July 8, 1959, including the death of Richard B. Fitzgibbon Jr. in 1956.

The names of 32 men were erroneously included in the memorial, and while those names remain on the wall, they have been removed from the databases and printed directories. The extra names resulted from a deliberate decision to err on the side of inclusiveness, with 38 questionable names being included. One person, whose name was added as late as 1992, had gone AWOL immediately upon his return to the United States after his second completed tour of duty. His survival only came to the attention of government authorities in 1996. These survivor names could be removed if the panel their name is on were to be replaced in the future.[13][14][15][16]

The Three Servicemen

A short distance away from the wall is another Vietnam memorial, a bronze statue named The Three Servicemen (sometimes called The Three Soldiers). The statue depicts three soldiers, purposefully identifiable as European American, African American, and Hispanic American. In their final arrangement, the statue and the Wall appear to interact with each other, with the soldiers looking on in solemn tribute at the names of their fallen comrades. The distance between the two allows them to interact while minimizing the effect of the addition on Lin's design.

Women's Memorial

The Vietnam Women's Memorial is a memorial dedicated to the women of the United States who served in the Vietnam War, most of whom were nurses. It serves as a reminder of the importance of women in the conflict. It depicts three uniformed women with a wounded soldier. It is part of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial and is located on National Mall in Washington, D.C., a short distance south of The Wall, north of the Reflecting Pool.

In Memory memorial plaque

A memorial plaque, authorized by an Act of Congress (Pub.L. 106–214), was dedicated on November 10, 2004 at the northeast corner of the plaza surrounding the Three Soldiers statue to honor veterans who died after the war as a direct result of injuries suffered in Vietnam, but who fall outside Department of Defense guidelines. The plaque is a carved block of black granite, 3 by 2 feet (0.91 by 0.61 m), inscribed "In memory of the men and women who served in the Vietnam War and later died as a result of their service. We honor and remember their sacrifice."

Ruth Coder Fitzgerald, the founder of The Vietnam War In Memory Memorial Plaque Project, worked for years to have the In Memory Memorial Plaque completed. The organization has been disbanded, but their web site is maintained by the Vietnam War Project at Texas Tech University.[17][18]

Ritual

Visitors to the memorial may take a piece of paper and place it over a name on the wall and rub a wax crayon or graphite pencil over it as a memento of their loved ones.[19] This is called rubbing.[20]

Visitors to the memorial began leaving sentimental items at the memorial at its opening. One story claims this practice began during construction when a Vietnam veteran threw the Purple Heart his brother received posthumously into the concrete of the memorial's foundation. Several thousand items are left at the memorial each year. The largest item left at the memorial was a sliding glass storm door with a full-size replica "tiger cage". The door was painted with a scene from Vietnam and the names of U.S. POWs and MIAs from the conflict.[21]

History

On April 27, 1979, four years after the Fall of Saigon, The Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, Inc. (VVMF), was incorporated as a non-profit organization to establish a memorial to veterans of the Vietnam War. Much of the impetus behind the formation of the fund came from a wounded Vietnam veteran, Jan Scruggs, who was inspired by the film The Deer Hunter, with support from fellow Vietnam veterans such as West Point and Harvard Business School graduate John P. Wheeler III.[4] Eventually, $8.4 million was raised by private donations. On July 1, 1980, a site covering two acres next to the Lincoln Memorial was chosen and authorized by Congress[4] where the World War I Munitions Building previously stood. Congress announced that the winner of a design competition would design the park. By the end of the year 2,573 registered for the design competition with a prize of $20,000. On March 30, 1981, 1,421 designs were submitted. The designs were displayed at an airport hangar at Andrews Air Force Base for the selection committee, in rows covering more than 35,000 square feet (3,300 m2) of floor space. Each entry was identified by number only, to preserve the anonymity of their authors. All entries were examined by each juror; the entries were narrowed down to 232, then 39. Finally, the jury selected entry number 1026, designed by Maya Lin.

Opposition to design and compromise

The selected design was very controversial, in particular, its unconventional design, its black color and its lack of ornamentation.[22] Some public officials voiced their displeasure, calling the wall "a black gash of shame."[23] Two prominent early supporters of the project, H. Ross Perot and James Webb, withdrew their support once they saw the design. Said Webb, "I never in my wildest dreams imagined such a nihilistic slab of stone."[24] James Watt, secretary of the interior under President Ronald Reagan, initially refused to issue a building permit for the memorial due to the public outcry about the design.[25] Since its early years, criticism of the Memorial's design faded. In the words of Scruggs, "It has become something of a shrine."[23]

Negative reactions to Maya Lin's design created a controversy; a compromise was reached by commissioning Frederick Hart (who had placed third in the original design competition) to produce a bronze figurative sculpture in the heroic tradition. Opponents of Lin's design had hoped to place this sculpture of three soldiers at the apex of the wall's two sides. Lin objected strenuously to this, arguing that this would make the soldiers the focal point of the memorial, and her wall a mere backdrop. A compromise was reached, and the sculpture was placed off to one side to minimize the impact of the addition on Lin's design. On October 13, 1982, the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts approved the erection of a flagpole to be grouped with sculptures.

Building the memorial

On March 11, 1982, the revised design was formally approved, and on March 26, 1982, the ground was formally broken. Stone for the wall came from Bangalore, Karnataka, India that was chosen because of its reflective quality.[4] Also, there was opposition to Swedish and Canadian stone as those countries were destinations for draft evaders. Stone cutting and fabrication were done in Barre, Vermont. The typesetting of the original 57,939 names on the wall was performed by Datalantic in Atlanta, Georgia. Stones were then shipped to Memphis, Tennessee where the names were etched. The etching was completed using a photoemulsion and sandblasting process. The negatives used in the process are in storage at the Smithsonian Institution.

The memorial was dedicated on November 13, 1982, as part of a five-day ceremony that began on November 10, 1982, presided over by President Ronald Reagan, and which involved a procession of tens of thousands of Vietnam War veterans.[4] About two years later the Three Soldiers statue was dedicated.

Timeline for those listed on the wall

- November 1, 1955 – Dwight D. Eisenhower deployed the Military Assistance Advisory Group, referred to now as MAAG, to train the South Vietnamese military units and secret police. However, the U.S. Department of Defense does not recognize this date since the men were supposedly training only the Vietnamese, so the officially recognized date is the formation of the Military Assistance Command Viet Nam, better known as MACV. This marked the official beginning of American involvement in the war as recognized by the memorial.

- June 8, 1956 – The first official death in Vietnam was Technical Sergeant Richard Bernard Fitzgibbon Jr., United States Air Force, of Stoneham, Massachusetts, who was murdered by another U.S.A.F. airman.

- October 21, 1957 – Capt. Harry Griffith Cramer, Jr., a graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, was killed near Nha Trang, Vietnam. He served in Korea, where he was injured and awarded the Purple Heart, as well as in Vietnam. He was the first US Army soldier to be killed in the line of duty in the Vietnam War. A street at Fort Lewis, Washington, is named in his honor. He is buried at the United States Military Academy, West Point, New York.

- July 8, 1959 – Chester M. Ovnand and Dale R. Buis were killed by guerrillas at Bien Hoa while watching the film The Tattered Dress. They are listed Nos. 1 and 2 at the wall's dedication. Ovnand's name is spelled on the memorial as "Oxnard," due to conflicting military records of his surname.

- April 30, 1975 – Fall of Saigon. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs uses May 7, 1975, as the official end date for the Vietnam War era as defined by 38 U.S.C. § 101.

- May 15, 1975 – 18 U.S. servicemen (14 Marines, two Navy corpsmen, and two Air Force crewmen) are killed on the last day of a rescue operation known as the Mayagüez incident with troops from the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia. They are the last servicemen listed on the timeline.

Since 1982, over 400 names have been added to the memorial, but not necessarily in chronological order. Some were men who died in Vietnam but were left off the list due to clerical errors. Others died after 1982, and their deaths were determined by the Department of Defense to be the direct result of their Vietnam service. For those who died during the war, their name is placed in a position that relates to their date of death. For those who died after the war, their name is placed in a position that relates to the date of their injury. Because space is usually not available in the exact right place, names are placed as close to their correct chronological position as possible, but usually not in the exact spot. The order could be corrected as panels are replaced.[26]

Furthermore, over 100 names have been identified as misspelled. In some cases, the correction could be done in place. In others, the name had to be chiseled again elsewhere, moving them out of chronological order. Others have remained in place, with the misspelling, at the request of their family.[27]

Addition of the Women's Memorial

The Women's Memorial was designed by Glenna Goodacre for the women of the United States who served in the Vietnam War. Before Goodacre's design was selected, two design entries had been awarded as co-finalists – one a statue and the other a setting – however, the two designs were unable to be reconciled.[28][29] Glenna Goodacre's entry received an honorable mention in the contest and she was asked to submit a modified maquette (design model). Goodacre's original design for the Women's Memorial statue included a standing figure of a nurse holding a Vietnamese baby, which although not intended as such, was deemed a political statement, and it was asked that this be removed. She replaced them with a figure of a kneeling woman holding an empty helmet. On November 11, 1993, the Vietnam Women's Memorial was dedicated. There is a smaller replica of that memorial at Vietnam Veterans Memorial State Park in Angel Fire, New Mexico.

Memorial plaque

On November 10, 2000, a memorial plaque, authorized by Pub.L. 106–214, honoring veterans who died after the war as a direct result of injuries suffered in Vietnam, but who fall outside Department of Defense guidelines was dedicated. Ruth Coder Fitzgerald, the founder of The Vietnam War In Memory Memorial Plaque Project, worked for years and struggled against opposition to have the In Memory Memorial Plaque completed. The organization was disbanded, but their web site[30] is maintained by the Vietnam War Project at Texas Tech University.[18]

Education center

In 2003, after some years of lobbying, the National Park Service and the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund won permission from Congress to build The Education Center at The Wall. A 37,000-square-foot (3,400 m2) two-story museum, located below ground just west of the Maya Lin-designed memorial, was proposed to display the history of the Vietnam War and the multiple design competitions and artworks which make up the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Vietnam Women's Memorial, and the Memorial Plaque.[31] The center would have also provided biographical details on and photographs of many of the 58,000 names listed on the Wall as well as the more than 6,600 servicemembers killed since 2001 fighting the War on Terror.[32] The $115-million museum would be jointly operated by the Park Service and the Fund.[31] A ceremonial groundbreaking for the project occurred in November 2012,[32] but insufficient fundraising led the Fund to cancel construction of the center in September 2018 and instead focus on digital education and outreach.[33][34][35]

Vietnam Veterans Memorial Collection

Items left at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial are collected by National Park Service employees and transferred to the NPS Museum Resource Center, which catalogs and stores all items except perishable organic matter (such as fresh flowers) and unaltered U.S. flags. The flags are redistributed through various channels.[36]

From 1992 to 2003, selected items from the collection were placed on exhibit at the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History as "Personal Legacy: The Healing of a Nation" including the Medal of Honor of Charles Liteky, who renounced it in 1986 by placing the medal at the memorial in an envelope addressed to then-president Ronald Reagan.

Inspired works

Traveling replicas

There are several transportable replicas of the Vietnam Veteran's Memorial created so those who are not able to travel to Washington, D.C., would be able to simulate an experience of visiting the Wall.

- Using personal finances, John Devitt founded Vietnam Combat Veterans, Ltd. With the help of friends, the half-size replica of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, named The Moving Wall,[37] was built and first put on display to the public in Tyler, Texas, in 1984. The Moving Wall visits hundreds of small towns and cities throughout the U.S., staying five or six days at each site. Local arrangements for each visit are made months in advance by veterans' organizations and other civic groups. The desire for a hometown visit of The Moving Wall was so high that the waiting list became very long. Vietnam Combat Veterans built a second structure of The Moving Wall. A third structure was added in 1989. In 2001, one of the structures was retired due to wear. By 2006, there had been more than 1,000 hometown visits of The Moving Wall. The count of people who visited The Moving Wall at each display ranges from 5,000 to more than 50,000; the total estimate of visitors is in the tens of millions. As the wall moves from town to town on interstates, it is often escorted by state troopers and up to thousands of local citizens on motorcycles. Many of these are Patriot Guard Riders, who consider escorting The Moving Wall to be a "special mission", which is coordinated on their website. As it passes towns, even when it is not planning a stop in those towns, local veterans organizations sometimes plan for local citizens to gather by the highway and across overpasses to wave flags and salute the Wall.[37] The first Moving Wall structure to retire has been on permanent display at the Veterans Memorial Amphitheater in Pittsburg, Kansas since 2004. The Memorial is open to the public with no admission fee, 24 hours a day, year-round.[38]

- Duluth, Minnesota holds the Northland Vietnam Veterans Memorial; a site that was dedicated on May 30, 1992.

- The Wall That Heals[39] is a traveling half-scale replica of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial started in 1996 by the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund. A 53-foot (16 m) tractor-trailer transports the 250-foot (76 m) wall replica and converts to a mobile Education Center at each stop, showing letters and memorabilia left at The Wall in Washington, D.C. and more details about those whose names are shown. This half-scale replica has been retired to permanent display in front of the James E. Van Zandt VA Medical Center in Altoona, PA. The VVMF has resumed a half-scale replica touring throughout the U. S. of The Wall That Heals. Their 2020 schedule can be found at 2020 Tour Schedule

- Created by the American Veterans Traveling Tribute, The Traveling Wall is an 80% replica Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall and is 360 feet (110 m) long and 8 feet (2.4 m) tall at its apex. It claims to be the largest traveling replica.

- Created by Vietnam and All Veterans of Brevard, Inc, The Vietnam Traveling Memorial Wall is a 3⁄5 scale of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial and is almost 300 feet (91 m) long and 6 feet (1.8 m) tall at the center.

- Created by Dignity Memorial, the Dignity Memorial Vietnam Wall is 3⁄4 scale of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

Fixed replicas

Located at 200 S. 9th Ave in Pensacola, Florida, the first permanent replica of the National Vietnam Memorial was unveiled on October 24, 1992. Now known as "Wall South," the half-size replica bears the names of all Americans killed or missing in Southeast Asia and is updated each Mother's Day. It is the centerpiece of Veterans Memorial Park Pensacola,[40] a five-and-one-half acre site overlooking Pensacola Bay, which also includes a World War I Memorial, a World War II Memorial, a Korean War Memorial, a Revolutionary War Memorial and a running series of plaques to honor local casualties from the Global War on Terror.[41] There is also a Purple Heart Memorial, a Marine Corps Aviation Bell Tower and a monument to the submarine lifeguards who rescued Navy pilots in World War II. A Global War on Terror Memorial is planned to be completed in 2017 and will include an artifact from the World Trade Center as a component of the sculpture.[42]

Located in Fox Park in Wildwood, New Jersey, The Wildwoods Vietnam Memorial Wall was unveiled and dedicated on May 29, 2010. The memorial wall is an almost half-size granite replica of the National Vietnam Memorial and the only permanent memorial north of the nation's capital.[43]

Plans for the Vietnam War Memorial located 401 East Ninth Street in Winfield, Kansas began in 1987 when friends who had gathered for a class reunion wanted to find a way to honor their fallen classmates. The project quickly grew from honoring only Cowley County servicemen to representing all 777 servicemen and nurses from Kansas who lost their lives or are missing in action from the Vietnam War.[44]

Located at Freedom Park in South Sioux City, Nebraska exists a half-scale replica of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial wall that duplicates the original design. Dedicated in 2014, the 250-foot wall is constructed with black granite mined from the same quarry in India as the original.[45]

Located in Layton, Utah, the Layton Vietnam Memorial Wall at 437 N Wasatch Dr, 84041, contains the names of all 58,000 Americans who died in the war. According to Utah Vietnam Veterans of America, the wall is 80 percent of the original size of the memorial in Washington, D.C., and it is the only replica of its size west of the Mississippi. The memorial was officially opened and dedicated on July 14, 2018.

Located in Elizabethtown, Kentucky, opened in 2018. This Vietnam Veteran's Memorial Wall is 360-feet long, an 80 percent scale of the one in Washington D.C.

There is a full-sized replica located in Perryville, Missouri.

Located in Augusta, Georgia, opened in 2019, the Augusta-CSRA Vietnam War Veterans Memorial is not a replica but follows the principles set forth by the national monument of honoring those fallen in Vietnam with inscriptions of the names, 169 total, who made the supreme sacrifice in Vietnam.[46]

As a memorial genre

The first US memorial to an ongoing war, the Northwood Gratitude and Honor Memorial in Irvine, California, is modeled on the Vietnam Veterans memorial in that it includes a chronological list of the dead engraved in dark granite. As the memorialized wars (in Iraq and Afghanistan) have not concluded, the Northwood Gratitude and Honor Memorial will be updated yearly. It has space for about 8000 names, of which 5,714 were engraved as of the Dedication of the Memorial on November 14, 2010.[47][48]

Cultural representations

The Vietnam Veteran's Memorial Wall inspired over 60 songs, showing how the war has been represented in subsequent decades, performed by professional musicians and Vietnam veterans.[49] The songs present patriotic tributes to the names on the Wall, the perspective of families and friends, as well as recriminations and anti-war sentiment. One of the first songs released on record was "The Wall" by Britt Small & Festival, who performed the song at the memorial in November 1982, and subsequently released as a 7" single. This was followed by "Who are the names on the Wall?", by Vietnam veterans Michael J. Martin and Tim Holiday, also released in 1982. In 1983, contemporary folk artist Michael Jerling released "Long Black Wall" on the "CooP Fast Folk Musical Magazine (Vol. 2, No. 4) - Political Song", published by Fast Folk. Commercially successful songs include: "More Than a Name on the Wall" (1989) by The Statler Brothers, which peaked at #6 on the Billboard Hot Country Singles chart; "The Big Parade" (1989) by 10,000 Maniacs on the album Blind Man's Zoo, which reached #13 in the US Billboard chart; Guns n' Roses song "Civil War" (1991), which referenced the memorial, and reaching #4 in the US Billboard rock charts. Other well-known songs include "The Wall" (2014) by Bruce Springsteen on his album High Hopes and "Xmas in February" (1989) by Lou Reed, released on the album New York.[50]

Vandalism

There have been hundreds of incidents of vandalism at the memorial wall. Some of the most notable cases are:

- In April 1988, when a swastika and various scratches were found etched in two of the panels.[51]

- In 1993, someone burned one of the directory stands at the entrance to the memorial.[52]

- On September 7, 2007, an oily substance was found by park rangers on the memorial's wall panels and paving stones. It was spread over an area of 50–60 feet (15–18 m). Memorial Fund founder Jan Scruggs deplored the scene, calling it an "act of vandalism on one of America's sacred places". The removal process took a few weeks to complete.[52]

See also

- List of public art in Washington, D.C., Ward 2

- List of Vietnam War memorials

- Northwood Gratitude and Honor Memorial

- Vietnam Forces National Memorial, Canberra

- Vietnam Veterans Memorial (The Wall-USA), an online memorial

- Vietnam Veterans of America, chartered by Congress and campaigns on issues important to Vietnam veterans

- Vietnam War Memorial, Hanoi

- The Virtual Wall, an online memorial

- The Wall That Heals, a 1997 film

References

Footnotes

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- Robbins, Eleanora I. (2001). Building Stones and Geomorphology of Washington, D.C.: The Jim O'Connor Memorial Field Trip. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.124.7887.

- Rasmussen, Kenneth (October 16, 2010). "The Post Could Have Better Explained Cracks in the Wall". Opinions. The Washington Post (Letter to the Editor). Retrieved October 16, 2010.

- Dupré, Judith (2007). Monuments: America’s History in Art and Memory. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6582-0.

- "Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund | Frequently Asked Questions". www.vvmf.org. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- "America's Wars Fact Sheet" (PDF). Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- Hagopian, Patrick (2011). The Vietnam War in American Memory: Veterans, Memorials, and the Politics of Healing. Univ of Massachusetts Press. p. 474. ISBN 1558499024.

- Ruane, Michael (October 7, 2010). "New cracks discovered in Wall at Vietnam Veterans Memorial". Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- Shannon, Don (February 7, 1990). "Vietnam Memorial Develops Thin Cracks : Veterans: The project's main fund-raiser starts a $1-million campaign to pay for unanticipated repairs. Who is at fault has yet to be determined". Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- "THE VIETNAM VETERANS MEMORIAL — A MODEL PARTNERSHIP ON AMERICA'S MALL BY JAN C. SCRUGGS, ESQ". January 20, 2012. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- "Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund – Founders of The Wall". www.vvmf.org. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- "The Memorial – The Wall".

- "Survivied". The Virtual Wall. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- "On Memorial To the Dead, 14 Who Live". February 11, 1991. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- Castaneda, Ruben (February 15, 1991). "38 VETERANS LISTED ON WALL MAY HAVE SURVIVED VIETNAM". Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- "Vietnam Memorial Fund: FAQs". Archived from the original on April 5, 2012.

- "The Vietnam War In Memory Memorial Plaque Project". Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- Dutill, The Vietnam Project, Michael (July 1, 2002). "The Vietnam Project Portal – Association Portal Page". www.vietnamproject.ttu.edu.

- "13 Things to Know About the Vietnam Veterans Memorial". The Daily Signal. November 13, 2014. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- Smaridge, Norah (July 27, 1975). "Tombstones, Manhole Covers and The Ancient Art of Rubbing". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

- "MRCE: Frequently Asked Questions (continued)". National Park Service. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- "Vietnam Veterans' Memorial Founder: Monument Almost Never Got Built".

- Garber, Kent (November 3, 2007). "A Milestone for a Memorial that Has Touched Millions". U.S. News and World Report. Retrieved November 11, 2009.

- Glass, Andrew (November 13, 2015). "Vietnam War Memorial dedicated, Nov. 13, 1982". Politico. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- Wills, Denise (November 1, 2007). "The Vietnam Memorial's History". The Washingtonian. Retrieved November 11, 2009.

- "Names Added". The Virtual Wall. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- "Vietnam Memorial Has Spelling Errors Set In Stone". February 24, 2014. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- Times, Irvin Molotsky and Special To the New York. "Sculptor Picked for Vietnam Memorial to Women".

- and, Eric Schmitt. "A Belated Salute to the Women Who Served".

- "Vietnam War In Memory Memorial Plaque Project". www.vietnamproject.ttu.edu.

- Neibauer, Michael (June 24, 2015). "Decade-long saga over $115M underground National Mall construction project nears resolution". Washington Business Journal. Retrieved March 26, 2017.

- Lin, C.j. (November 28, 2012). "Ground is broken for education center at Vietnam Veterans Memorial". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved March 26, 2017.

- "Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund changes direction of Education Center campaign". www.vvmf.org. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- "Plan to build Vietnam War education center on the National Mall is abandoned". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- Sisk, Richard (September 21, 2018). "After $23M Spent, Plans for Vietnam Wall Education Center Have Been Scrapped". Military.com. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- "MRCE: Frequently Asked Questions". National Park Service. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- "Local AMVETS to Salute Wall". Greenville Advocate. July 17, 2007.

- "Vietnam Wall". Veterans Memorial.

- "Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund – The Wall That Heals: Mobile Exhibit". www.vvmf.org.

- http://www.veteransmemorialparkpensacola.com/land/Welcome

- Giberson, Art (2015). Wall South: Veterans Memorial Park. Pensacola, FL: CreateSpace.

- "Veterans Memorial Park Pensacola". Veterans Memorial Park Foundation.

- "The Wildwoods Vietnam Memorial Wall". Wildwood, NJ.

- "Kansas Vietnam War Memorial". Winfield, KS.

- "Vietnam memorial replica dedicated in South Sioux City".

- Dawson, Drew (March 29, 2019). "Vietnam War Memorial Unveiled in Augusta". WGPB Georgia Public Broadcasting. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- "The Northwood Gratitude and Honor Memorial". northwoodmemorial.com.

- Kang, Sukhee (February 22, 2010). "Letter". City of Irvine. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- Hugo Keesing and Wouter Keesing with C.L. Yarbrough & Justin Brummer. "Vietnam on Record: An Incomplete Discography". University of Maryland. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- Brummer, Justin. "Vietnam War: Veterans Memorial Wall Songs". RYM. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- "Vandals Scratch Swastika on Face of Viet Veterans Memorial". Los Angeles Times. United Press International. May 3, 1988.

- "Substance on Vietnam Memorial is Vandalism". Oswego, NY: WTOP-TV. Retrieved September 2, 2010..

Works cited

- Vietnam Veterans Memorial (Leaflet). National Park Service. GPO:2004—304–377/00203.

- The National Parks: Index 2001–2003. Washington: United States Department of the Interior.

Further reading

- Ashabranner, Brent K. (1989). Always to Remember: The Story of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. New York: Putnam.

- ——— (1998). Their Names to Live: What the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Means to America. Brookfield, CT: Twenty-first Century Press.

- Berdahl, Daphne. "Voices at the Wall: Discourses of Self, History and National Identity at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial". History & Memory: Studies in Representation of the Past. 6 (Fall–Winter 1994): 88–124.

- Blair, Carole; Jeppeson, Marsha S. & Pucci, Enrico Jr. (August 1991). "Public Memorializing in Postmodernity: The Vietnam Veterans Memorial as Prototype". Quarterly Journal of Speech. 77: 263–288. doi:10.1080/00335639109383960.

- Capasso, Nicholas (1998). The National Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Context: Commemorative Public Art in America, 1960–1997 (PhD Thesis). Rutgers University.

- Carlson, A. Cheree & Hocking, John E. (September 1988). "Strategies of Redemption at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial". Western Journal of Speech Communication. 52: 203–215. doi:10.1080/10570318809389636.

- Carney, Lora S. (1993). "Not Telling Us What to Think: The Vietnam Veterans Memorial". Metaphor and Symbolic Activity. 8 (3): 211–219. doi:10.1207/s15327868ms0803_6.

- Danto, Arthur (August 31, 1985). "The Vietnam Veterans Memorial". The Nation. pp. 152–155.

- Dupré, Judith (2007). Monuments: America’s History in Art and Memory. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6582-0.

- Ellis, Caron S. (Summer 1992). "So Old Soldiers Don't Fade Away: The Vietnam Veterans Memorial". Journal of American Culture. 15: 25–28. doi:10.1111/j.1542-734x.1992.t01-1-00025.x.

- Ehrenhaus, Peter (March 1988). "Silence and Symbolic Expression". Communication Monographs. 55: 41–57. doi:10.1080/03637758809376157.

- Foss, Sonja K. (Summer 1986). "Ambiguity as Persuasion: The Vietnam Veterans Memorial". Communication Quarterly. 34: 326–340. doi:10.1080/01463378609369643.

- Friedman, Daniel S. (November 1995). "Public Things in the Modern City: Belated Notes on Tilted Arc and the Vietnam Veterans Memorial". Journal of Architectural Education. 49: 62–78. doi:10.1080/10464883.1995.10734669.

- Giberson, Art (2015). Wall South: Veterans Memorial Park. Pensacola, FL: CreateSpace.

- Griswold, Charles L. (Summer 1986). "The Vietnam Veterans Memorial and the Washington Mall: Philosophical Thoughts on Political Iconography". Critical Inquiry. 12: 688–719. doi:10.1086/448361.

- Haines, Harry (1986). "'What Kind of War?': An Analysis of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial". Critical Studies in Mass Communucation. 3: 1–20. doi:10.1080/15295038609366626.

- Hass, Kristin Ann (1998). Carried to the Wall: American Memory and the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Hass, Kristin Ann (2015). Sacrificing Soldiers on the National Mall. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Hess, Elizabeth (1987). "Vietnam: Memorials of Misfortune". In Williams, Reese (ed.). Unwinding the Vietnam War: From War into Peace. Seattle: Real Comet Press. pp. 261–270.

- Hubbard, William (Winter 1984). "A Meaning for Monuments". The Public Interest. 74: 17–30.

- Katakis, Michael (1988). The Vietnam Veterans Memorial. New York: Crown.

- Lopes, Sal (1987). The Wall: Images and Offerings from the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. New York: Collins.

- McLeod, Mary (1989). "The Battle for the Monument: The Vietnam Veterans Memorial". In Lipstadt, Helene (ed.). The Experimental Tradition. New York: Rizzoli. pp. 115–137.

- Morrissey, Thomas F. (2000). Between the Lines: Photographs from the National Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

- Nau, Terry L. (2013). "Chapter 11: "The Wall" Heals Vietnam Vets". Reluctant Soldier... Proud Veteran: How a cynical Vietnam vet learned to take pride in his service to the USA. Leipzig: Amazon Distribution GmbH. pp. 101–112. ISBN 9781482761498. OCLC 870660174.

- Ochsner, Jeffrey Karl (February 1997). "A Space of Loss: The Vietnam Veterans Memorial". Journal of Architectural Education. 50: 156–171. doi:10.1080/10464883.1997.10734719.

- Palmer, Laura (1987). Shrapnel in the Heart: Letters and Remembrances from the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. New York: Random House.

- Resnicoff, Arnold E. (2009). "Dedication Prayer for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial". In Moore, James P. Jr. (ed.). The Treasury of American Prayer. Doubleday. p. 317.

- Scott, Grant F. (Fall 1990). "Meditations in Black: The Vietnam Veterans Memorial". Journal of American Culture. 13: 37–40. doi:10.1111/j.1542-734x.1990.1303_37.x.

- Scruggs, Jan C. & Swerdlow, Joel L. (1985). To Heal a Nation: The Vietnam Veterans Memorial. New York: Harper & Row.

- Sturken, Marita (Summer 1991). "The Wall, the Screen, and the Image: The Vietnam Veterans Memorial". Representations. 35: 118–142. doi:10.1525/rep.1991.35.1.99p00683.

- Wagner-Pacific, Robin & Schwartz, Barry (1991). "The Vietnam Veterans Memorial: Commemorating a Difficult Past". The American Journal of Sociology. 97: 376–420. doi:10.1086/229783.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- "Tenth Anniversary Commemoration". C-SPAN. November 11, 1992. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

A number of dignitaries spoke at a ceremony marking the tenth anniversary of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial on a rainy day in Washington, DC. The keynote speakers, former Lebanese hostage Terry Anderson and Vice President-elect Al Gore, Jr., honored the Vietnam veterans living and dead for their service to their country. Sen. Gore also pledged to investigate every POW and MIA from the Vietnam War, and also improve the veterans health care system. Following the speeches, Sen. Gore and Mr. Scruggs placed a wreath at the base of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, and a lone bugle player played 'Taps'.