Nuns of the Battlefield

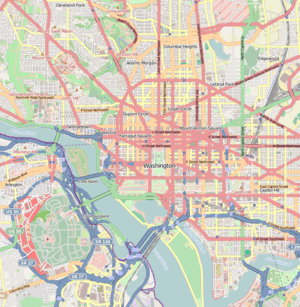

Nuns of the Battlefield is a public artwork made in 1924 by Irish artist Jerome Connor, located at the intersection of Rhode Island Avenue NW, M Street, and Connecticut Avenue NW, in Washington, D.C., United States. A tribute to the more than 600 nuns who nursed soldiers of both armies during the American Civil War, it is one of two monuments in the District that mark women's roles in the conflict.[3][4] It is a contributing monument to the Civil War Monuments in Washington, D.C., listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In 1993, it was surveyed for the Smithsonian Institution's Save Outdoor Sculpture! program.

| Nuns of the Battlefield | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Jerome Connor |

| Year | 1924 |

| Type | Bronze |

| Dimensions | 182.88 cm × 274.32 cm (72.00 in × 108.00 in) |

| Location | Washington, D.C., United States |

| Owner | National Park Service |

Nuns of the Battlefield | |

| |

| Location | Washington, D.C. |

| Coordinates | 38°54′20.83″N 77°2′24.89″W |

| Part of | Civil War Monuments in Washington, DC. |

| NRHP reference No. | 78000257[1] |

| Added to NRHP | September 20, 1978 [2] |

Description

The face of the sculpture has a large bronze bas relief panel showing 12 nuns dressed in traditional habit. This panel is installed on a rectangular granite slab that sits on a granite base. Each end of the slab has a bronze female figure seated. The proper right-side figure has wings, a helmet, robes, and armor to look like an angel, representing patriotism. Sitting, she holds a shield in her proper left hand and a scroll in her lap with her proper right hand. She is weaponless, to represent peace. On the proper left side of the slab, another winged figure sits wearing a long dress, a bodice, and a scarf around her head to represent the angel of Peace. Her hands are folded on her lap.

The lower right side of the relief is signed: JEROME CONNOR 1924

The lower left side of the relief is inscribed:

- BUREAU BROS.

- BRONZE FOUNDERS PHILA

- ENN

On the granite above the relief is inscribed:

- THEY COMFORTED THE DYING, NURSED THE WOUNDED, CARRIED HOPE TO

- THE IMPRISONED, GAVE IN HIS NAME A DRINK OF WATER TO THE THIRSTY.

On the granite below the relief:

- TO THE MEMORY AND IN HONOR OF

- THE VARIOUS ORDERS OF SISTERS

- WHO GAVE THEIR SERVICES AS NURSES ON BATTLEFIELDS

- AND IN HOSPITALS DURING THE CIVIL WAR.

On the rear of the slab near the base is inscribed:

- ERECTED BY THE LADIES AUXILIARY TO THE ANCIENT ORDER OF HIBERNIANS OF AMERICA. A.D. 1924

- BY AUTHORITY OF THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES.[3]

Artist

Born in Ireland in 1874, Jerome Connor moved at the age of 14 with his family to Massachusetts. His father was a stonemason, which led to Connor's jobs in New York as a sign painter, stonecutter, bronze founder, and machinist. Inspired by his father's work and his own experience, Connor used to steal his father's chisels as a child and carve figures into rocks.

In 1899, he moved into the Roycroft Institution where he helped with blacksmithing and eventually began making terracotta busts and reliefs. During four years at Roycroft, he became well known as a sculptor, and was commissioned to create civic works in bronze for placement in Washington, D.C., Syracuse, East Aurora, New York, San Francisco, and Ireland.

In 1925, he moved back to Ireland and opened his own studio in Dublin, but found few patrons and his work slowed. He died on August 21, 1943, of heart failure.[5] There is a plaque in his honour on Infirmary Road, overlooking Dublin's Phoenix Park, with the words of his friend the poet Patrick Kavanagh:

- He sits in a corner of my memory

- With his short pipe, holding it by the bowl,

- And his sharp eye and his knotty fingers

- And his laughing soul

- Shining through the gaps of his crusty wall.

History

The idea for the monument originated with Ellen Jolly, president of the women's auxiliary branch of the Ancient Order of Hibernians who grew up hearing stories of battlefield tales told by nuns. Proposing the sculpture just after the turn of the century, her request was denied by the War Department until proof of service was provided. For ten years Jolly worked to gather evidence and presented it to Congress in 1918.[4]

The sculpture was authorized by Congress on March 29, 1918 with the agreement that the government would not fund it. A committee, led by Jolly, on behalf of the Ancient Order of the Hibernians, raised $50,000 for the project.[3][4]

Jerome Connor was chosen since he focused on Irish Catholic themes, being one himself.[4]

Acquisition

A construction delay was caused due to the final location of the sculpture. Jerome Connor wanted the sculpture either at Arlington National Cemetery or at the Pan American Union Building. Neither choice was supported by the War Department or the DC Fine Arts Commission and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers decided on the final location near Dupont Circle. Once the location was chosen, the Arts Commission requested that the sculpture be changed by Connor. They requested that he alter the size, move inscriptions on the front, rearrange the front steps and make the angels "active." A year later, in 1919, Congress finally approved of the design.[4] Construction began on July 28, 1924.[3]

Finally, Jerome Connor ended up suing the Ancient Order of the Hibernians for nonpayment.[3]

The monument was dedicated on September 20, 1924 as part of a weekend long meeting of over 5,000 Catholics from all over the country. One nun, Sister Magdeline of the Sisters of Mercy, who served in the Civil War attended the event and was received with a "thunderous applause." Archbishop O'Connell of Boston spoke and upon finishing, Jolly revealed the sculpture by removing an American flag that covered it. Sailors hoisted signal flags spelling "faith, hope and charity" and a flock of white pigeons were released.[4][6]

Information

The nuns represented on the relief are from the Sisters of St. Joseph, Carmelites, Dominican Order, Ursulines, Sisters of the Holy Cross, Poor Sisters of St. Francis, Sisters of Mercy, Congregation of the Sisters of Our Lady of Mercy, Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul, Sisters of Charity of Nazareth, Sisters of Providence of Saint Mary-of-the-Woods, and Congregation of Divine Providence.[7]

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "Civil War Monuments in Washington, DC". National Park Service. September 20, 1978. Archived from the original on February 20, 2013. Retrieved August 10, 2011.

- Save Outdoor Sculpture! (1993). "Nuns of the Battlefield, (sculpture)". SOS!. Smithsonian. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- Jacob, Kathryn Allmong. Testament to Union: Civil War monuments in Washington, Part 3. JHU Press, 1998, p. 125-126.

- "Jerome Connor 1874–1943 Sculptor". Jerome Connor. Annascual. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- John W. Tuohy. "Nuns of the Battlefield". When Washington Was Irish. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- Craig Swain (2008). "Nuns of the Battlefield". Northwest in Washington, District of Columbia — The American Northeast (Mid-Atlantic). The Historical Marker Database. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

Further reading

- J. Goode, Washington Sculpture, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008. ISBN 0-8018-8810-7, A cultural history of outdoor sculpture in the Nation's capital.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nuns of the Battlefield Memorial, Washington, D.C.. |