Water tower

A water tower is an elevated structure supporting a water tank constructed at a height sufficient to pressurize a water distribution system for the distribution of potable water, and to provide emergency storage for fire protection. In some places, the term standpipe is used interchangeably to refer to a water tower.[1] Water towers often operate in conjunction with underground or surface service reservoirs, which store treated water close to where it will be used.[2] Other types of water towers may only store raw (non-potable) water for fire protection or industrial purposes, and may not necessarily be connected to a public water supply.

Water towers are able to supply water even during power outages, because they rely on hydrostatic pressure produced by elevation of water (due to gravity) to push the water into domestic and industrial water distribution systems; however, they cannot supply the water for a long time without power, because a pump is typically required to refill the tower. A water tower also serves as a reservoir to help with water needs during peak usage times. The water level in the tower typically falls during the peak usage hours of the day, and then a pump fills it back up during the night. This process also keeps the water from freezing in cold weather, since the tower is constantly being drained and refilled.

History

Although the use of elevated water storage tanks has existed since ancient times in various forms, the modern use of water towers for pressurized public water systems developed during the mid-19th century, as steam-pumping became more common, and better pipes that could handle higher pressures were developed. In the United Kingdom, standpipes consisted of tall, exposed, n-shaped pipes, used for pressure relief and to provide a fixed elevation for steam-driven pumping engines which tended to produce a pulsing flow, while the pressurized water distribution system required constant pressure. Standpipes also provided a convenient fixed location to measure flow rates. Designers typically enclosed the riser pipes in decorative masonry or wooden structures. By the late 19th-Century, standpipes grew to include storage tanks to meet the ever-increasing demands of growing cities.[1]

Many early water towers are now considered historically significant and have been included in various heritage listings around the world. Some are converted to apartments or exclusive penthouses.[3] In certain areas, such as New York City in the United States, smaller water towers are constructed for individual buildings. In California and some other states, domestic water towers enclosed by siding (tankhouses) were once built (1850s–1930s) to supply individual homes; windmills pumped water from hand-dug wells up into the tank in New York.

Water towers were used to supply water stops for steam locomotives on railroad lines. Early steam locomotives required water stops every 7 to 10 miles (11 to 16 km).

Design and construction

A variety of materials can be used to construct a typical water tower; steel and reinforced or prestressed concrete are most often used (with wood, fiberglass, or brick also in use), incorporating an interior coating to protect the water from any effects from the lining material. The reservoir in the tower may be spherical, cylindrical, or an ellipsoid, with a minimum height of approximately 6 metres (20 ft) and a minimum of 4 m (13 ft) in diameter. A standard water tower typically has a height of approximately 40 m (130 ft).

Pressurization occurs through the hydrostatic pressure of the elevation of water; for every 10.20 centimetres (4.016 in) of elevation, it produces 1 kilopascal (0.145 psi) of pressure. 30 m (98.43 ft) of elevation produces roughly 300 kPa (43.511 psi), which is enough pressure to operate and provide for most domestic water pressure and distribution system requirements.

The height of the tower provides the pressure for the water supply system, and it may be supplemented with a pump. The volume of the reservoir and diameter of the piping provide and sustain flow rate. However, relying on a pump to provide pressure is expensive; to keep up with varying demand, the pump would have to be sized to meet peak demands. During periods of low demand, jockey pumps are used to meet these lower water flow requirements. The water tower reduces the need for electrical consumption of cycling pumps and thus the need for an expensive pump control system, as this system would have to be sized sufficiently to give the same pressure at high flow rates.

Very high volumes and flow rates are needed when fighting fires. With a water tower present, pumps can be sized for average demand, not peak demand; the water tower can provide water pressure during the day and pumps will refill the water tower when demands are lower.

Using wireless sensor networks to monitor water levels inside the tower allows municipalities to automatically monitor and control pumps without installing and maintaining expensive data cables.[4]

Architecture

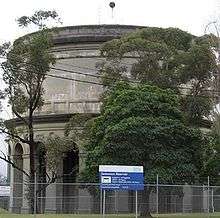

Water towers can be surrounded by ornate coverings including fancy brickwork, a large ivy-covered trellis or they can be simply painted. Some city water towers have the name of the city painted in large letters on the roof, as a navigational aid to aviators and motorists. Sometimes the decoration can be humorous. An example of this are water towers built side by side, labeled HOT and COLD. Cities in the United States possessing side-by-side water towers labeled HOT and COLD include Granger, Iowa; Canton, Kansas; Pratt, Kansas, and St. Clair, Missouri; Eveleth, Minnesota at one time had two such towers, but no longer does.[5] When a third water tower was built next to the Okemah, Oklahoma set of Hot and Cold towers, the town briefly considered naming it "Running", but eventually decided to use "Home of Woody Guthrie". The House in the Clouds in Thorpeness, located in the English county of Suffolk, was built to resemble a house in order to disguise the eyesore, whilst the lower floors were used for accommodation. When the town was connected to the mains water supply, the water tower was dismantled and converted to additional living space.

The first and original "Mushroom" – Svampen in Swedish – was built in Örebro in Sweden in the early 1950s and later copies were built around the world including Saudi Arabia and Kuwait.[6]

Many small towns in the United States use their water towers to advertise local tourism, their local high school sports teams, or other locally notable facts.[7]

Since the water tower is often the highest point in the town (in small towns), antennas, public address systems, cameras and tornado warning sirens are sometimes placed on them, as well.

Many water towers serve manufacturing and other commercial facilities. These are often decorated with the name of the company that the water tower serves.

Sapp Bros. truck stops use a water tower with a handle and spout – looking like a coffee pot – as the company logo. Many of their facilities have decorated actual water towers (presumably non-functional) on-site.

Worldwide

The structures seen here illustrate three architectural approaches to incorporating these tanks in the design of a building. From left to right, a fully enclosed and ornately decorated brick structure, a simple unadorned roofless brick structure hiding most of the tank but revealing the top of the tank, and a simple utilitarian structure that makes no effort to hide the tanks or otherwise incorporate them into the design of the building.]] The technology dates to at least the 19th century, and for a long time New York City required that all buildings higher than six stories be equipped with a rooftop water tower.[8] Two companies in New York build water towers, both of which are family businesses in operation since the 19th century.[8]

The original water tower builders were barrel makers who expanded their craft to meet a modern need as buildings in the city grew taller in height. Even today, no sealant is used to hold the water in. The wooden walls of the water tower are held together with steel cables or straps, but water leaks through the gaps when first filled. As the water saturates the wood, it swells, the gaps close and become impermeable.[9] The rooftop water towers store 25,000 to 50,000 litres (5,500 to 11,000 imp gal; 6,600 to 13,200 US gal) of water until it is needed in the building below. The upper portion of water is skimmed off the top for everyday use while the water in the bottom of the tower is held in reserve to fight fire. When the water drops below a certain level, a pressure switch, level switch or float valve will activate a pump or open a public water line to refill the water tower.[9]

Architects and builders have taken varied approaches to incorporating water towers into the design of their buildings. On many large commercial buildings, water towers are completely hidden behind an extension of the facade of the building. For cosmetic reasons, apartment buildings often enclose their tanks in rooftop structures, either simple unadorned rooftop boxes, or ornately decorated structures intended to enhance the visual appeal of the building. Many buildings, however, leave their water towers in plain view atop utilitarian framework structures.

Water towers are common in India, where the electricity supply is erratic in most places.

If the pumps fail (such as during a power outage), then water pressure will be lost, causing potential public health concerns. Many U.S. states require a "boil-water advisory" to be issued if water pressure drops below 20 pounds per square inch (140 kPa). This advisory presumes that the lower pressure might allow pathogens to enter the system.

Water towers are often regarded as monuments of civil engineering. Some have been converted to serve modern purposes, as for example, the Wieża Ciśnień (Wrocław water tower) in Wrocław, Poland which is today a restaurant complex. Others have been converted to residential use.[10]

Historically, railroads that used steam locomotives required a means of replenishing the locomotive's tenders. Water towers were common along the railroad. The tenders were usually replenished by water cranes, which were fed by a water tower.

Some water towers are also used as observation towers, and some restaurants, such as the Goldbergturm in Sindelfingen, Germany, or the second of the three Kuwait Towers, in the State of Kuwait. It is also common to use water towers as the location of transmission mechanisms in the UHF range with small power, for instance for closed rural broadcasting service, amateur radio, or cellular telephone service.

In hilly regions, local topography can be substituted for structures to elevate the tanks. These tanks are often nothing more than concrete cisterns terraced into the sides of local hills or mountains, but function identically to the traditional water tower. The tops of these tanks can be landscaped or used as park space, if desired.

Spheres and spheroids

The Chicago Bridge and Iron Company has built many of the water spheres and spheroids found in the United States.[11] The website World's Tallest Water Sphere describes the distinction between a water sphere and water spheroid thus:

A water sphere is a type of water tower that has a large sphere at the top of its post. The sphere looks like a golf ball sitting on a tee or a round lollipop. A cross section of a sphere in any direction (east-west, north-south, or top-bottom) is a perfect circle. A water spheroid looks like a water sphere, but the top is wider than it is tall. A spheroid looks like a round pillow that is somewhat flattened. A cross section of a spheroid in two directions (east-west or north-south) is an ellipse, but in only one direction (top-bottom) is it a perfect circle. Both spheres and spheroids are special-case ellipsoids: spheres have symmetry in 3 directions, spheroids have symmetry in 2 directions. Scalene ellipsoids have 3 unequal length axes and three unequal cross sections.[12]

The Union Watersphere is a water tower topped with a sphere-shaped water tank in Union, New Jersey[13] and characterized as the World's Tallest Water Sphere. A Star Ledger article[14] suggested a water tower in Erwin, North Carolina completed in early 2012, 219.75 ft (66.98 m) tall and holding 500,000 US gallons (1,900 m3),[15] had become the World's Tallest Water Sphere. However photographs of the Erwin water tower revealed the new tower to be a water spheroid.[16] The water tower in Braman, Oklahoma, built by the Kaw Nation and completed in 2010, is 220.6 ft (67.2 m) tall and can hold 350,000 US gallons (1,300 m3).[17] Slightly taller than the Union Watersphere, it is also a spheroid.[18] Another tower in Oklahoma, built in 1986 and billed as the "largest water tower in the country", is 218 ft (66 m) tall, can hold 500,000 US gallons (1,900 m3), and is located in Edmond.[19][20]

The Earthoid, a perfectly spherical tank located in Germantown, Maryland is 100 ft (30 m) tall and holds 2,000,000 US gallons (7,600 m3) of water. The name is taken from it being painted to resemble a globe of the world.[21][22][23][24] The golf ball-shaped tank of the water tower at Gonzales, California is supported by three tubular legs and reaches about 125 ft (38 m) high.[25][26][27]

The Watertoren (or Water Towers) in Eindhoven, Netherlands contain three spherical tanks, each 10 m (33 ft) in diameter and capable of holding 500 cubic metres (130,000 US gal) of water, on three 43.45 m (142.6 ft) spires were completed in 1970.[28][29]

Tallest

| Tower | Year | Country | Town | Pinnacle height | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swisscom-Sendeturm St. Chrischona | 1984 | St. Chrischona | 250 m (820 ft) | ||

| Kuwait Towers, Tower A | 1979 | Kuwait City | 187 m (613 ft) | ||

| Kuwait Towers, Tower B | 1979 | Kuwait City | 146 m (479 ft) | ||

| Waldenburg TV Tower | 1959 | Waldenburg | 145 m (475 ft) | partially guyed tower consisting of water tower and antenna mast guyed to the ground as pinnacle, antenna mast was dismantled in 2008 | |

| Mechelen-Zuid water tower | 1978 | Mechelen | 143 m (469 ft) | combined water and telecommunications tower | |

| Ginosa Water Tower | 1915 | Ginosa | 130 m (426.5 ft) | [31] |

Alternatives

Alternatives to water towers are simple pumps mounted on top of the water pipes to increase the water pressure.[32] This new approach is more straightforward, but also more subject to potential public health risks; if the pumps fail, then loss of water pressure may result in entry of contaminants into the water system.[33] Most large water utilities do not use this approach, given the potential risks.

Notable

Australia

Austria

- Wolfersberg Water Tower (Water tower with transmission antenna)

Belgium

Brazil

- Nave Espacial de Varginha in Varghina

Canada

- Guaranteed Pure Milk bottle in Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Croatia

Denmark

Germany

- Lüneburg Water Tower

- Heidelberg TV Tower (TV tower with water reservoir)

- Mannheim Water Tower (built 1886–1889)

Italy

- Ginosa Water Tower, 122 metres (400 ft) tall[34]

Netherlands

- Amsterdamsestraatweg Water Tower in Utrecht

- Eindhoven Water Towers in Eindhoven

- Poldertoren in Emmeloord

- Water Tower Simpelveld in Simpelveld

- Water Tower Hellevoetsluis in Hellevoetsluis

Poland

Slovenia

Sweden

- Vanadislundens water reservoir (Stockholm)

United Kingdom

- Cardiff Central Station Water Tower

- Dock Tower in Grimsby

- House in the Clouds in Thorpeness, Suffolk

- Jumbo in Colchester, Essex

- Norton Water Tower in Norton, Cheshire

- Tilehurst Water Tower in Reading

- Tower Park in Poole, Dorset

- Cranhill, Garthamlock and Drumchapel in Glasgow, and Tannochside just outside the city

United States

- Brooks Catsup Bottle Water Tower near Collinsville, Illinois

- Chicago Water Tower in Chicago, Illinois

- Florence Y'all Water Tower in Florence, Kentucky

- Leaning Water Tower in Groom, Texas

- Peachoid next to I-85 on the edge of Gaffney, South Carolina

- Union Watersphere in Union Township, New Jersey

- Volunteer Park Water Tower in Capitol Hill, Seattle, Washington

- Warner Bros. Water Tower in Burbank, California (In the animated TV series Animaniacs, it was used to incarcerate the characters Yakko, Wakko, and Dot, as well as to serve as their home.)

- Weehawken Water Tower in Weehawken, New Jersey

- Ypsilanti Water Tower in Ypsilanti, Michigan (Winner of the Most Phallic Building contest in 2003)[35]

Standpipe

There were originally over 400 standpipe water towers in the United States, but very few remain today, including:[36][37]

- Belton Standpipe in Belton, South Carolina (also in Allendale and Walterboro)

- Belton Standpipe in Belton, Texas

- Bellevue Standpipe (actually a water tank, not a tower), in Boston, Massachusetts

- Chicago Water Tower, in Chicago, Illinois

The Chicago Water Tower

The Chicago Water Tower - Cochituate standpipe, in Boston, Massachusetts

- Eden Park Stand Pipe, in Cincinnati

- Evansville Standpipe (a steel tower), in Evansville, Wisconsin

- Fall River Waterworks, in Fall River, Massachusetts

- Forbes Hill Standpipe, in Quincy, Massachusetts

- Louisville Water Tower, in Louisville, Kentucky

- North Point Water Tower, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin

- Reading Standpipe (demolished in 1999 and replaced by a modern steel tower), in Reading, Massachusetts

- St. Louis, Missouri has three standpipe water towers which are on the National Register of Historic Places.

- Bissell Tower (also known as the Red Tower)

- Compton Hill Tower

- Grand Avenue Water Tower

- Thomas Hill Standpipe, in Bangor, Maine

- Ypsilanti Water Tower, in Ypsilanti, Michigan

- Bremen Historic Standpipe in Bremen, Indiana

Gallery

See also

- Architectural structure

- List of nonbuilding structure types

- American and Canadian Water Landmark

- Caldwell Tanks

- Gas holder, a similar utility storage structure

- Hyperboloid structure

- Pittsburgh-Des Moines Steel Co.

- Pumped-storage hydroelectricity

- Water tank

References

- "New England Water Supplies – A Brief History, Marcis Kempe, MWRA, NEWWA Journal, September 2006, pages 96-99" (PDF). Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Burton, William Kinnimond (14 March 1894). The Water Supply of Towns and the Construction of Waterworks: A Practical Treatise for the Use of Engineers and Students of Engineering. Lockwood. p. 127. Retrieved 14 March 2018 – via Internet Archive.

Waterworks water tower design and location.

- "10 Industrial Water Towers Converted Into Awesome, Modern Homes". 17 August 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Banner Engineering (November 2009), Application Notes

- "Hot and Cold Water Tower". Ohiobarns.com. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- "A mushroom water tower". New Scientist. Vol. 11 no. 244. Reed Business Information. 20 July 1961. p. 162. ISSN 0262-4079. Retrieved 14 March 2018 – via Google Books.

- "Water tower slogans". Comcast. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Elliott, Debbie (2 December 2006). "Wondering About Water Towers". All Things Considered. National Public Radio.

- Charles, Jacoba (3 June 2007). "Longtime Emblems of City Roofs, Still Going Strong". The New York Times.

- Amies, Nick (10 August 2011). "A Water Tower Near Brussels". Retrieved 14 March 2018 – via NYTimes.com.

- "Waterspheroid" (PDF). CBI. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- "Water Sphere versus Water Spheroid". The World's Tallest Water Sphere. World's Tallest Water Sphere. June 2009. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- Westerggaard, Barbara, New Jersey A guide to the state, Rutgers University Press, ISBN 0-8135-3685-5

- Rose, Lisa (22 February 2012), "Despite challenge, Union Township water tower remains a Jersey landmark", The Star-Ledger, retrieved 21 February 2012

- Philliops, Gregor (11 May 2011). "Erwin's new water tower will be among tallest on East Coast". The Fayetteville Observer. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- "World's Tallest Water Sphere Title Safe for Now". The World's Tallest Water Sphere. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- "Water Tower – Braman, Oklahoma". Waymarking.com. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- "World's Tallest Water Sphere?". The World's Tallest Water Sphere. 22 December 2010. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- "Edmond Huskies". Waymarking.com. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- "Largest Water Tower". Center for Land Use Interpretation. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- Gaines, Danielle (2 March 2011). "Germantown's Earthoid water tower could be up for a makeover WSSC to choose new painted design for tank next month". Gazette. Net. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ""Earthoid" Water Storage Tank – Germantown MD". Waymarking.com. 7 September 2009. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- "Makeover The Earthoid gets a refresh". Germantown Patch. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- "A whole new world Earthoid water tank makeover update". Germantown Patch. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- "Gonzales Round Municipal Tank". Waymarking.com. 22 April 2009. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- "Gonzales Water Tower". Waymarking.com. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- "Gonzales Water Tower". Wikimapia. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- "Water Tower Eindhoven". Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- "Water Tower". Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- plantaardignieuwsbrief12010.pdf

- "Il fantastico mondo dell'acqua con gli occhi di chi sa guardare". la Voce dell'Acqua (in Italian).

- "Rainwater Pumps or Pressure Tanks". www.harvesth2o.com. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- "Pressure in the Distribution System". water.me.vccs.edu. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- "Ginosa Water Tower". Emporis. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- "The Most Phallic Building in the World". Cabinet.

- Harris, NiNi (1986). "Treasured Towers". In Hannon, Robert E. (ed.). St. Louis: Its Neighborhoods and Neighbors, Landmarks and Milestones. St. Louis, MO: Buxton & Skinner Printing Co.

- "Watertowers". builtstlouis.net. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Water towers. |