Warragamba Dam

Warragamba Dam is a heritage-listed dam in Warragamba, Wollondilly Shire, New South Wales, Australia. It is a concrete gravity dam, which creates Lake Burragorang, the primary reservoir for water supply for the Australian city of Sydney, New South Wales.

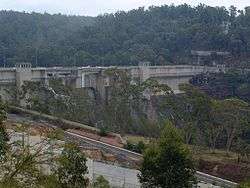

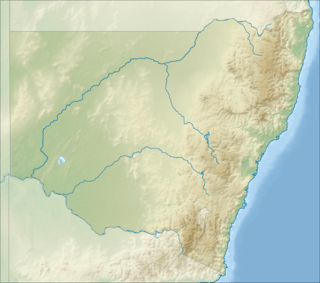

| Warragamba Dam | |

|---|---|

Warragamba Dam wall | |

Location of the Warragamba Dam in New South Wales | |

| Country | Australia |

| Location | Warragamba, New South Wales |

| Coordinates | 33°52′59″S 150°35′44″E |

| Purpose | Potable water supply |

| Status | Operational |

| Construction began | 1948 |

| Opening date | 14 October 1960 |

| Owner(s) | WaterNSW |

| Dam and spillways | |

| Type of dam | Gravity dam |

| Impounds | Warragamba River |

| Height | 142 m (466 ft) |

| Length | 351 m (1,152 ft) |

| Width (base) | 104 m (341 ft) |

| Dam volume | 3,000,000 tonnes (3,300,000 short tons; 3,000,000 long tons) |

| Spillways | Two |

| Spillway type | Controlled chute spillways with five crest gates and a central drum; automatic operation |

| Reservoir | |

| Creates | Lake Burragorang |

| Total capacity | 2,031 GL (4.47×1011 imp gal; 5.37×1011 US gal) |

| Catchment area | 9,051 km2 (3,495 sq mi) |

| Surface area | 75 km2 (29 sq mi) |

| Maximum length | 52 km (32 mi) |

| Maximum water depth | 105 m (344 ft) |

| Normal elevation | 180 m (590 ft) |

| Power Station | |

| Operator(s) | Eraring Energy |

| Commission date | 1959 |

| Type | Conventional |

| Turbines | 1 |

| Installed capacity | 50 MW |

| Website Warragamba Dam at WaterNSW | |

| Official name | Warragamba Emergency Scheme |

| Type | State heritage (built) |

| Designated | 18 November 1999 |

| Reference no. | 1376 |

| Type | Water Supply Reservoir/ Dam |

| Category | Utilities - Water |

| Builders | Metropolitan Water Sewerage and Drainage Board |

The dam impounds the Coxs, Kowmung, Nattai, Wingecarribee, Wollondilly, and Warragamba rivers, within the Hawkesbury-Nepean catchment;[1] and the dam wall is located approximately 65 kilometres (40 mi) to the southwest of Sydney central business district, near the town of Wallacia. Constructed between 1948 and 1960, the dam created capacity for a reservoir of 2,031 gigalitres (4.47×1011 imp gal; 5.37×1011 US gal) and is fed by a catchment area of 9,051 square kilometres (3,495 sq mi). The surface area of the lake covers 75 square kilometres (29 sq mi) of the now flooded Burragorang Valley. Enhancements to the dam were completed in 2009, including the addition of an auxiliary spillway to manage extreme flood events.[2]

The dam was devised as part of a collective engineering response to Sydney's critical water shortage during World War II and was originally known as the Warragamba Emergency Scheme. The dam is located in the outer south-western Sydney suburb of Warragamba in the Wollondilly Shire local government area New South Wales, Australia. The dam was designed and built by the Metropolitan Water Sewerage and Drainage Board from 1948 to 1960. The property is owned by WaterNSW, an agency of the Government of New South Wales. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 18 November 1999.[3] A small hydroelectric power station is incorporated into the design of the dam and may operate at times of peak discharge; but has rarely generated power in recent years.[4]

In December 2004, the dam dropped to 38.8% of capacity, the lowest on record to date, lower than the previous lowest of 45.4% in March 1983.[5] In early March 2012, the dam spilled for the first time in fourteen years, as a result of heavy rainfall in the catchment during February 2012. This spill followed a period of prolonged drought which saw the dam fall to historic lows of below 33% in 2007.[6]

Overview

The Warragamba River flows through a gorge that varies in width from 300 to 600 metres (980 to 1,970 ft), and is 100 metres (330 ft) in depth. This gorge opens at its upper end into a large valley, the Burragorang Valley. This river configuration allows for a relatively short but high dam wall, in the gorge, to impound a vast quantity of water.[7]

In 1845, Paweł Strzelecki drew attention to the Warragamba River as a water supply catchment; in 1867, supporters proposed a dam. Between 1867 and 1946, supporters proposed various schemes before the site and design of the current dam received approval. In 1940, a weir and pumping station, known as the Warragamba Emergency Scheme, reached completion, just downstream of the main dam site.[7]

In 1943 the Metropolitan Water, Sewerage and Drainage Board invited the geologist William Browne to investigate a proposed site. Browne found a more suitable site and continued as geological adviser until completion.[8] The site was reviewed and approved by Dr John Savage, considered the pre-eminent expert in this field, and formally accepted by the Metropolitan Water, Sewerage and Drainage Board on 2 October 1946.[7] The Board appointed Thomas Upton as the engineer.

Dam construction began in 1948 and was completed in 1960. The resulting dam of the Warragamba River formed Lake Burragorang, which is one of the largest reservoirs for urban water supply in the world.

The dam wall comprises 1,612,000 cubic yards (1,232,000 m3) of concrete. It was laid as interlocking blocks roughly 17 metres (56 ft) on each side, which were later grouted together to form a continuous, monolithic wall. It is so large that engineers had to use two techniques to prevent the temperature from becoming too hot as the concrete set. One was to add ice to the wet concrete, the first application of this technique in Australia. The other was to embed cooling pipes into the concrete and circulate chilled water through the pipes. As a result, the dam wall was cooled in a few months instead of the estimated 100 years it would have taken to cool naturally.[7]

Spillway

The main spillway has five crest gates: A central drum gate with a 27 metres (89 ft) clear span with a pair of radial gates on each side. Each radial gate has a 12 metres (39 ft) clear span. The drum gate is hinged along the upstream edge to the upstream crest and lowers into the dam wall to allow water to flow over it. When fully open, it forms a continuation of the crest profile.[7] All gates open automatically as the dam passes full water level, or can be manually opened.[7][9] The auxiliary spillway is normally closed by a series of fuse plugs that are designed to be washed away in the event of an extreme flood event.[2]

As originally designed, the dam could safely withstand a peak inflow of 500,000 cubic feet per second (14,000 m3/s), leading to a peak discharge of 354,000 cubic feet per second (10,000 m3/s) down the spillway.[7] Following a 1987 and 1989 re-evaluation of the potential rainfall and flood risks, the New South Wales Government authorised for the dam wall to be raised by 5 metres (16 ft) and constructed an auxiliary spillway on the east bank of the dam.[9]

Re-engineering works

In 2006, the Warragamba Deep Water Storage Recovery Project, part of the Metropolitan Water Plan, penetrated the base of the dam wall to allow the previously inaccessible lowest water in the reservoir to be available. This new outlet was below the minimum level required for gravity flow, which delivered water from the existing outlets. The project constructed a new pumping station downstream of the dam. The new pumping station is within the Emergency Scheme pumping station chamber. This project provided access to eight per cent more water or approximately six months of extra supply. On 15 April 2006, the project reached a major milestone when it increased the available storage from 1,857 gigalitres (6.56×1010 cu ft) to 2,027 gigalitres (7.16×1010 cu ft).

Other recent major work includes a complete upgrade of the three passenger lifts within the dam wall, an upgrade of the traveling crest crane and a complete upgrade of the four water supply outlets in the valve house, which includes the replacement of the major valves. A full electrical upgrade is currently in advanced planning stage, as is a mechanical upgrade that will address the drum gate and four radial gates.

History

One of the first places in the Gundungurra traditional homelands that most appealed to the Anglo-Celtic settlers were the river flats of the Burragorang Valley (now flooded under Warragamba Dam). Even before the valley was officially surveyed in 1827-8, many early settlers were already squatting on blocks that they planned to officially occupy following the issue of freehold title grants. From the Burragorang Valley and using Aboriginal pathways, other valleys to the west were occupied and developed by the settlers with construction of outstations and stock routes. These cattle entrepreneurs were then followed by cedar-wood extractors and miners.[3]

The Gundungurra traditional owners resisted the taking of their lands, and, relying on various laws of the colony at the time, continually applied for official ownership. Although their individual claims failed, in some kind of recognition of the significance of the designated tracts of land claimed, six Aboriginal Reserves (under the control of the NSW Aborigines Protection Board) were formally declared in the Burragorang Valley. Even after these reserves were revoked, many of the traditional owners remained, quietly refusing to leave their traditional homelands.[3]

Finally pushed into the "Gully", a fringe development in West Katoomba from about 1894, the Gully community stayed together for more than 60 years until dispossessed of the Gully by the then Blue Mountains Shire Council so a group of local businessmen could develop a speedway that became known as the Catalina Race Track. The Gully people kept talking about areas of land they had walked in as children - the nearby Megalong and Kanimbla Valleys and the Burragorang Valley. They knew of the profound significance of these valleys for their parents and grandparents.[12][3]

Warragamba Emergency Scheme

In 1910, Ernest de Burgh, Chief Engineer for Water Supply and Sewerage, in the NSW Public Works Department prepared a proposal for a dam on the Warragamba River and followed it up in 1918 with more detailed plans. His proposals were passed onto the newly formed Metropolitan Water and Sewerage and Drainage Board in 1925 when it took over from the P.W.D. The completion of the Warragamba Emergency Scheme required during its peak 1,000 waged employees at the Headworks, and a further 1,000 on the Pipeline. All buildings used in the construction of the Emergency Scheme were designed for later re-use as cottages for the future maintenance and operations personnel. Some of these buildings were relocated from elsewhere. The main works office was the original police station at the Nepean Dam site.[3]

The construction site for the Warragamba Emergency Scheme was located on the east bank of the Warragamba River. Access to the site was along the road currently known as Weir Road. Major elements of the construction works still extant include the weir, a 10-cable cableway, shads, batching plants, roads, electrical substation, chlorination plant, maintenance staff accommodation, balance reservoir, Megarritys Bridge, water pumping station, tunnels, and associated pipelines.[3]

Catchment

The catchment area is 9,050 square kilometres (3,490 sq mi). The areas closest to the lake, making up around 30% of the total catchment, are restricted access special areas. Most of the rest of the catchment consists of cleared farming land and contains large and small towns, which discharge treated sewage into the catchment.

Although the engineers did not design Warragamba Dam as a flood control measure, it can mitigate flooding by holding floodwaters back while the reservoir fills.

Dam level crises and water restrictions

There have been times when drought has seriously depleted the dam. In March 1983, Lake Burragorang's level reached a low of 45.4% of capacity, only to reach maximum level in the mid 1990s; as a consequence the gates were opened. Between 1998 and 2007 the catchment area experienced extremely low rainfall, and on 8 February 2007 it recorded an all time low of 32.5% of capacity.[13]

The New South Wales State Government tried to reduce this risk by implementing water restrictions[14] and commissioned the construction of a desalination plant, at Kurnell. Heavy rains between June 2007 and February 2008 restored the dam level to around 67%. Despite this, Level 3 water restrictions remained in place until 21 June 2009. On 29 February 2012, it was reported that the dam was likely to overflow for the first time in fourteen years, due to continuing heavy rain in the region.[15] The dam began spilling at 18:53 (AEDT) on 2 March 2012 and again on 20 April 2012.[6][16][17]

Statistical overview

| Key dam structures | |

|---|---|

| Height | 142 metres (466 ft) |

| Length | 351 metres (1,152 ft) |

| Thickness at top | 8.5 metres (28 ft) |

| Thickness at base | 104 metres (341 ft) |

| Width of central spillway | 94.5 metres (310 ft) |

| Width of auxiliary spillway (at mouth) | 190 metres (620 ft) |

| Length of auxiliary spillway | 700 metres (2,300 ft) |

| Hydro-electric plant capacity | 50 megawatts (67,000 hp) |

| Key reservoir statistics | |

|---|---|

| Available storage (when full) | 2,027 gigalitres (7.16×1010 cu ft) |

| Total capacity (when full) | 2,031 gigalitres (7.17×1010 cu ft) |

| Surface area | 75 square kilometres (29 sq mi) |

| Length of lake | 52 kilometres (32 mi) |

| Length of foreshores | 354 kilometres (220 mi) |

| Deepest point | 105 metres (344 ft) |

| Catchment area | 9,051 square kilometres (3,495 sq mi) |

| Average annual rainfall | 840 millimetres (33 in) |

Access and recreation

Warragamba Dam was also a popular picnic spot for Sydneysiders but access to the public had been restricted since 1999 due to A$240 million of upgrades in that time. It reopened to the public on 8 November 2009.[18]

Access to the dam wall and terrace gardens opened from 23 December 2012 to 28 January 2013 at weekends and public holidays.

Heritage listing

The Emergency Scheme is representative of the collective engineering response to Sydney's critical water shortage during the Second World War period. It was the first stage in the storage and extraction of water from the Warragamba River, and was preliminary to the Waragamba Dam. All of the components are excellent examples of the civil engineering skills of the times; the Balance Reservoir is particularly significant because it provides a stilling pool downstream of Warragamba Dam for the purpose of flood discharge; the group of five cottages associated with the construction of the dam are considered to be of high significance because they housed the operations staff between 1940 and 1959. These have since been incorporated into the Warragamba township, one of the largest townships in the Shire of Wollondilly.[3]

The Warragamba Emergency Scheme was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 18 November 1999 having satisfied the following criteria.[3]

The place possesses uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

This item is assessed as historically rare statewide. This item is assessed as scientifically rare statewide.[3]

References

- "Warragamba Dam". Sydney Catchment Authority. Government of New South Wales. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- "Warragamba Dam Auxiliary Spillway". Sydney Catchment Authority. Government of New South Wales. 31 May 2011. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- "Warragamba Emergency Scheme". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H01376. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "Annual Report" (PDF). Eraring Energy. 2012. p. 18. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- Warragamba Dam hits lowest level by ABC News Friday, 10 December 2004

- "SCAN" (PDF). The Sydney Catchment Authority’s quarterly newsletter. Sydney Catchment Authority. Autumn 2012. p. 3. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- Aird, W. V. (1961). The water supply, sewerage, and drainage of Sydney. Sydney: Metropolitan Water, Sewerage and Drainage Board. pp. 106–117. An account of the development and history of the water supply, sewerage, and drainage systems of Sydney and the near south coast from their beginnings with the first settlement to 1960.

- Vallance, T. G. "Browne, William Rowan (1884–1975)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- "Warragamba: A dam full of myths". Sydney Catchment Authority. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- "Hydro Power Stations: Warragamba". Generation Portfolio. Eraring Energy. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012.

- "Hydro Power Stations: Warragamba". Generation Portfolio. Eraring Energy. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013.

- Johnson, 2009, 4.

- "Bulk Water Storage & Supply Report". Sydney Catchment Authority. Government of New South Wales. 8 February 2007.

- "Mandatory Water Restrictions". Sydney Water Corporation. Archived from the original on 28 May 2007.

- "Warragamba Dam to spill Friday morning: BoM". ABC TV. Australia. 2 March 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- "Warragamba Dam finally spills". Sydney Morning Herald. AAP. 2 March 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- "Warragamba bursts, flood warning issued". Sydney Morning Herald. AAP. 20 April 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- "Warragmba (sic) Dam will re-open to public". ABC News. Australia. 13 July 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

Bibliography

- "Warragamba Dam". 2007.

- Attraction Homepage (2007). "Warragamba Dam".

- Johnson, Dianne (2009). 'The Katoomba Gully People's resistance to dispossession' in History Council of NSW Bulletin, Winter.

- Graham Brooks and Associates Pty Ltd (1996). Sydney Water Heritage Study.

Attribution

![]()

External links

![]()