Vittorio Veneto

Vittorio Veneto is a city and comune situated in the Province of Treviso, in the region of Veneto, Italy, in the northeast of Italy, between the Piave and the Livenza rivers.

Vittorio Veneto | |

|---|---|

| Città di Vittorio Veneto | |

| |

Coat of arms | |

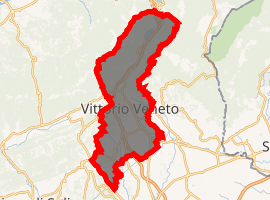

Location of Vittorio Veneto

| |

Vittorio Veneto Location of Vittorio Veneto in Italy  Vittorio Veneto Vittorio Veneto (Veneto) | |

| Coordinates: 45°59′N 12°18′E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Veneto |

| Province | Treviso (TV) |

| Frazioni | Carpesica, Confin, Cozzuolo, Fadalto, Formeniga, Longhere, Nove, San Lorenzo, San Giacomo di Veglia |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Antonio Miatto |

| Area | |

| • Total | 82 km2 (32 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 138 m (453 ft) |

| Population (31 December 2015)[2] | |

| • Total | 28,232 |

| • Density | 340/km2 (890/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Vittoriesi |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 31029 |

| Dialing code | 0438 |

| Patron saint | St. Titian and Augusta of Treviso |

| Saint day | January 16, August 22 |

| Website | Official website |

Name

The city is an amalgamation of two former comuni, Cèneda and Serravalle, which were joined into one municipality in 1866 and named Vittorio after the King of Italy, Vittorio Emanuele II. The battle fought nearby in November 1918 became generally known as the Battle of Vittorio Veneto, and the city's name was officially changed to Vittorio Veneto in July 1923.[3] [4]

Geography

The Meschio River, whose source is located in the Lapisina Valley, a few miles north of the city, passes down through the town from Serravalle through the district that bears its name. The north of Vittorio Veneto is straddled by mountains including the majestic Col Visentin. To the east is the state park and forest of Cansiglio which summits at Monte Pizzoc; to the west, a hill region including Valdobbiadene, where Prosecco wine is produced; and to the south is the commercial town of Conegliano.

Administrative subdivisions

According to the communal statute, the commune does not recognize any fraction within itself. There are a number of numerous distinct areas and local autonomy is guaranteed to the following seven districts (Followed by the main settlements that are part of it).

- 1 - Val Lapisina: Fadalto, Nove, San Floriano, Savassa, Forcal, Longhere, Maren, Fais.

- 2 - Serravalle: Sant'Andrea, San Lorenzo, Serravalle

- 3 - Center: Centro, Salsa

- 4 - Costa-Meschio: Costa, Meschio

- 5 - Ceneda: Alta and Ceneda Bassa (Saints Peter and Paul)

- 6 - San Giacomo: San Giacomo di Veglia

- 7 - Val dei Fiori: Carpesica, Cozzuolo, Formeniga

History

Ancient period

The area was occupied in ancient times by Veneti and perhaps Celts. A pagan sanctuary was in use on Monte Altare by Veneti, Celts, and Romans.

During the 1st century BC Emperor Augustus established a Castrum Cenetense at the foot of an important pass northward towards Bellunum in what is now the heart of Serravalle to defend Opitergium and the Venetian plain to the south. To the immediate south of the castrum there developed a settlement called a vicus in what is now Ceneda and Meschio. While its precise course has not been determined, the Via Claudia Altinate running north from the Via Postumia seems to have passed the Roman castrum and vicus on its eastern side. Meanwhile, there remains evidence of typical Roman land surveying (centuratio) with cardines being associated with the present day Via Rizzera and Via Cal Alta (in the commune of Cappella Maggiore) and a decumanus identified with the Va Cal de Livera.[5] This implies Ceneta became more than a mere vicus during the Roman period.

Late antiquity

The ancient pieve of Sant'Andrea in Bigonzo in the northeast of the town, on the southern end of Serravalle, attests to the presence of Christianity in the area by the 4th century.

In the early 5th century, Emperor Honorius seems to have named a certain Marcellus count (comes) of Ceneta. Ceneta and Serravalle were among the places in Venetia devastated by Attila the Hun, but later refortified under the rule of Theodoric, king of the Ostrogoths.[6]

Byzantine writer, Agathias Scholasticus [7] as well as the Latin poet Venantius Fortunatus,[8] from nearby Valdobbiadene, are witnesses to the existence of the town of Ceneta in the 6th century. Agathias recounts how during Justinian's Gothic War, Ceneda changed hands between the Ostrogoths, Franks, and Byzantines. In fact, after the Byzantines had seized Venetia from the Ostrogoths, they turned their attention to conquering central and southern Italy. In the spring of 553, while Narses was engaging the Ostrogoths, the Franks led by the brothers Leutari and Buccelin took a large part of Venetia and sought refuge in Ceneta, holding it sometime in the spring of 554.

In 568, the Lombards invaded Italy and Ceneda was irrevocably captured from the Byzantines. Lombard social and military colonies called fara seem to have been established at Farra d'Alpago to the north of Ceneda and at Farra di Soligo to the west. It was perhaps at this time or perhaps still later that Ceneda made into the seat of one of 36 Lombard duchies. The Lombards constructed a castle, now called castello di San Martino near the heart of Ceneda on a strategic mountain which overlooks the town. By 667, the Duchy of Ceneda was certainly in existence and grew in size when, according to Paul the Deacon it acquired some of the territory of Oderzo after that city's destruction by the Lombards.[9]

In 685, the Lombard King Grimoald I organized Ceneda into an ecclesiastical diocese, assigning to it a large part of the territory that had been under the care of the suppressed diocese of Oderzo. The diocese of Ceneda was within the metropolitan jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Aquileia. At the foot of the same height upon which the duke's castle had been built, a cathedral was constructed. St. Titian, Bishop of Oderzo, whose relics are contained in the present cathedral, was named as co-patron of the diocese along with St. Augusta, a virgin martyr from Serravalle.

Carolingian period

With the defeat of the Lombards in 774, Ceneda entered into the Frankish sphere. It seems the duke of Ceneda remained loyal to Charlemagne even when the Lombard dukes of Cividale, Treviso, and Vicenza rebelled the following year.

Middle Ages

In 994, the Holy Roman Emperor Otto III invested the bishop of Ceneda with the title and prerogatives of count and authority as temporal lord of the city. The 12th, 13th, and part of the 14th centuries were turbulent for Ceneda and Serravalle. During this time, the bishop of Ceneda was forced into the role of count, and thus, to take part in the politics of Northern Italy and even joining the Lombard League against the Holy Roman Empire. Ceneda also faced threats from its neighbors and in 1147 was attacked by the commune of Treviso. Only the mediation of the pope led to the restitution of what had been stolen, including the relics of St. Titian. In 1174, Serravalle became a fief of the Da Camino family. Ceneda and Serravalle would subsequently be contested by the da Romano family and the Patriarchs of Aquileia. In 1328, the area fell into the hands of the Scaligeri.[6]

In 1307, Bishop Francesco Ramponi ceded the territory of Portobuffolé to Tolberto da Camino in exchange for county of Tarzo (also called Castelnuovo) which included Corbanese, Arfanta, Colmaor and Fratta. In Fratta, authority was invested in a vice-count of the bishop.

Venetian period

On December 19, 1389, Ceneda was peacefully incorporated into the Venetian Republic. Its bishops still retained authority as counts. However, in 1447 and in 1514 bishops Francesco and Oliviero, respectively, ceded to the Republic the right of civil investiture within the territory of Ceneda, reserving for themselves and their successors authority over the commune itself and a few villas. The privileges of Ceneda's bishops as counts were definitively revoked by the Republic in 1768.

Under Venetian rule, the urban development of Ceneda remained concentrated around the cathedral while the rest of the commune remained primarily agricultural with homes either scattered far and wide or sometimes organized in tiny clusters. Serravalle, however, which had come under Venetian rule in 1337 rose to its greatest splendor under the Serenissima, even eclipsing Ceneda in economic and urban development.

In 1411, an Hungarian army led by Pippo Spano attacked Ceneda and destroyed the episcopal archives. Both Ceneda and Serravalle suffered during the War of Cambrai.

A significant Jewish community grew in Ceneda throughout the Venetian period. Lorenzo Da Ponte, a librettist to Mozart, was a Jewish native of Ceneda, who took the bishop of Ceneda's name when he was baptized a Roman Catholic.

Napoleonic era

In March 1797, the French army of Massena entered the towns putting an end to Venetian rule. By the Treaty of Campoformio, the area passed to the rule of the Holy Roman Empire. From 1805 until 1814 Ceneda and Serravalle were incorporated into Napoleon's Kingdom of Italy.

Austrian period

After the Fall of Napoleon, the area was given with the rest of Venetia to the Austrian Empire.

Italian period

On November 22, 1866, soon after the Veneto was annexed by the Kingdom of Italy, Ceneda and Serravalle were joined into one municipality named after the King of Italy, Vittorio Emanuele.

During the First World War, Vittorio was occupied by Austro-Hungarian forces. In October 1918, Vittorio was the site of the last battle between Italy and Austria-Hungary during World War I. It led to the victory of Italy over the Austro-Hungarian Empire (Austrian-Italian Armistice of Villa Giusti) effective on 4 November 1918.

The word "Veneto", was attached to the city's name in 1923. Subsequently, many streets in other parts of Italy have been named Via Vittorio Veneto.

The Italian victory at the Battle of Vittorio Veneto led to the town lending its name as a military honor. Thus, in the 1930s, a battleship was named Vittorio Veneto. In the 1960s, a flight deck cruiser, the flagship of the Italian Navy, was given the same name. In 1968, a military medal called the Order of Vittorio Veneto Order (Ordine di Vittorio Veneto) was awarded to Italian veterans who had participated honorably for at least six months during the First World War.

List of (Count)-Bishops of Ceneda/Vittorio Veneto

Bishops of Ceneda

[Some series begin with Vindemius (579–591?), Ursinus (680–?), and Satinus (731–?).]

- Valentinianus (712–740)

- Maximus (741–790)

- Dulcissimus (c. 793–?)

- Ermonius (c. 827–?)

- Ripaldus (885–908)

Coterminously Bishops of Ceneda and Counts of Ceneda

- Sicardo (962–997), given title of count by Holy Roman Emperor

- Gauso (c. 998–?)

- Bruno (1021)

- Elmengero (1021–1031)

- Almanguino (1050)

- Giovanni (1074)

- Roperto (1124)

- Sigismondo (1130)

- Azzone Degli Azzoni (1138–1152)

- Aimone (1152)

- Sgisfredo (1170–1187)

- Matteo Da Siena (1187–1216)

- Gerardo (1217)

- Alberto Da Camino (1220–1242)

- Guarnieri Da Polcenigo (1242–1251)

- Ruggero (1252–1267)

- Biaquino Da Camino (1257)

- Alberto Da Collo (1257–1260)

- Odorico (1260–1261)

- Prosapio Novello (1261–1279)

- Marco Da Fabiane (1279–1285)

- Piero Calza (1286–1300)

- Francesco Arpone (1300–1310), first count of Tarzo

- Manfredo Da Collalto (1310–1320)

- Francesco Ramponi (1320–1348)

- Gualberto De'Orgoglio (1349–1374)

- Oliverio (1374–1377)

- Andrea Calderini (1378–1381?)

- Giorgio Torti (1381–1383)

- Marco De'Porris (1383–1394), after 1389 bishops retain title of count but with duties of civil magistrates of the Venetian Republic

- Martino Franceschini (1394–1399)

- Piero Marcello (1399–1409)

- Antonio Correr (bishop) (1409–1445)

- Piero Leoni (1445–1474)

- Nicolò Trevisan (1474–1498)

- Francesco Brevio (1498–1508)

- Marino Grimani (1508–1517)

- Domenico Grimani (1517–1520)

- Giovanni Grimani (1520–1531)

- Marino Grimani (1532–1540)

- Giovanni Grimani (1540–1545), second time

- Marino Grimani (1545–1546)

- Michele Della Torre (1547–1586), named cardinal 1583

- MarcAntonio Mocenigo (1586–1597), erected diocesan seminary

- Leonardo Mocenigo (1599–1623)

- Piero cardinal Valier (1623–1625), transferred to Padua

- Marco Giustiniani (1625–1631)

- Marcantonio Bragadin (1631–1639), transferred to Vicenza

- Sebastiano Pisani (1639–1653)

- Albertino Barisoni (1653–1667)

- Piero Leoni (1667–1691)

- Marc Antonio Agazzi (1692–1710)

- Francesco Trevisan (1710–1725)

- Benedetto De Luca (1725–1739)

- Lorenzo da Ponte (1740–1768), born Venice, last count-bishop

Bishops of Ceneda[10]

- Giannagostino Gradenigo, O.S.B. (19 Sep 1768 – 16 Mar 1774 Died)

- Giampaolo Dolfin, C.R.L. (27 Jun 1774 – 28 Jul 1777) transferred to Bergamo

- Marco Zaguri (15 Dec 1777 – 26 Sep 1785) transferred to Vicenza

- Pietro Antonio Zorzi, C.R.S. (3 Apr 1786 – 24 Sep 1792) transferred to Udine

- Giambenedetto Falier, O.S.B. (24 Sep 1792 – 22 Oct 1821)

- Giacomo Monico (16 May 1823 – 9 Apr 1827) translated to Venice

- Bernardo Antonino Squarcina, O.P. (15 Dec 1828 – 27 Jan 1842) transferred to Adria

- Manfredo Giovanni Battista Bellati (30 Jan 1843 – 28 Sep 1869)

- Corradino Cavriani (27 Oct 1871 – 11 Feb 1885) Resigned as bishop

- Sigismondo Brandolini Rota (27 Mar 1885 – 8 Jan 1908)

- Andrea Caron (8 Jan 1908 – 29 Apr 1912) transferred to Genua

- Rodolfo Caroli (28 Jul 1913 – 28 Apr 1917) Appointed Apostolic Internuncio to Bolivia

- Eugenio Beccegato (29 Aug 1917 – 13 May 1939)

Bishops of Vittorio Veneto

- Eugenio Beccegato (13 May 1939 – 17 Nov 1943)

- Giuseppe Zaffonato (27 Sep 1945 – 31 Jan 1956) transferred to Udine

- Giuseppe Carraro (9 Apr 1956 – 15 Dec 1958) transferred to Verona

- Albino Luciani (15 Dec 1958 – 15 Dec 1969) transferred to Venice, elected Pope in 1978 as John Paul I

- Antonio Cunial (9 Mar 1970 – 10 Aug 1982)

- Eugenio Ravignani (7 Mar 1983 – 4 Jan 1997) transferred to Trieste

- Alfredo Magarotto (31 May 1997 – 3 Dec 2003) Retired

- Giuseppe Zenti (3 Dec 2003 – 8 May 2007) transferred to Verona

- Corrado Pizziolo (19 Nov 2007 – )

Civil Administration (Mayors) during the Italian Republic

- Giovanni Poldemengo (1946-1951) Italian Communist Party

- Vittorio Della Porta (1951-1956) Christian Democrat

- Ferruccio Faggin (1956-1960) Italian Socialist Party

- Enrico Talin (1960-1961) Christian Democrat Party

- Mario Ulliana (1961-1965) Christian Democrat Party

- Aldo Toffoli (1965-1975) Christian Democrat Party

- Giorgio Pizzol (1975-1982 Italian Communist Party

- Franco Concas (1982-1988) Italian Socialist Party

- Mario Botteon (1988-1995) Christian Democrat Party

- Antonio Della Libera (1995-1999) Center Left Party

- Giancarlo Scottà (1999-2009) Lega Nord Party

- Gianantonio Da Re (2009-2014) Lega Nord Party

- Roberto Tonon (2014-2019) Center Left Party

- Antonio Miatto (2019- ) Lega Nord Party

Culture

Every year, the Concorso Nazionale Corale "Trofei Città di Vittorio Veneto" takes place at Vittorio Veneto. The best choirs from all over Italy compete.

The city is also host to a violin competition.

Language

| Form ("to be") | Cenedese | Venetian | Latin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infinitive | èsar | èser | esse |

| 1st Person Sing. | mi són | mi só(n) | ego sum |

| 2nd Person Sing. | ti te sé | ti ti si | tu es |

| 3rd Person Sing. | lu 'l é | lu xè | ille est |

| 1st Person Plur. | noiàltri sén | nu sémo | nos sumus |

| 2nd Person Plur. | voiàltri sé | vu sé | vos estis |

| 3rd Person Plur. | lori i é | lori xè | illi sunt |

The local Venetian dialect, called "Cenedese," or since the fusion of Ceneda and Serravalle, "Vittoriese," pertains more to the northern variant of Venetian, such as the dialect of Belluno, but it also shares features with the central variant of Treviso due to the influence of Venice.[11]

Characteristics of Cenedese distinguishing it from Venetian include the frequent dropping of final "-o", for example, Venetian "gòto" ("cup") is gòt in Cenedese. When this occurs leaving a final "-m", the "-m" is further nasalized to an "-n". Thus, for example, Venetian "sémo" ("we are") is "sén" in Cenedese.

Another rustic feature of Cenedese is that the first person singular of indicative verbs usually ends in "-e" rather than in "-o." Thus, Cenedese "mi magne" is equivalent to Venetian "mi magno" ("I eat"), "mi vede" ("I see") is "mi vedo," and "mi dorme" ("I sleep") is "mi dormo.

A northern feature of Cenedese, shared with Bellunese, is its refusal to attach "ghe" onto the verb "avér" ("to have") as is done in the dialects of Venice, Padua, and Treviso. Thus, where Venetian says "mi gò" ("I have") or "ti ti gà" ("you (sing.) have"), Cenedese says "mi ò" and "ti te à," respectively.

Overall, Cenedese remains intelligible to speakers of other dialects of the Venetian language.

People

- Albino Luciani (Pope John Paul I) – bishop of Vittorio Veneto from 1958 to 1969.

- Lorenzo Da Ponte – opera librettist for Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

- Ferdinando Botteon (Born 1904); Italian violinist.

- Marcantonio Flaminio (born 1498) – Renaissance humanist.

- Emanuela Da Ros (born 1959) – children's books writer.

- Francesca Segat (born 1983) – Italian butterfly swimmer.

- Giampietro Bontempi – pianist.

- Ilario Castagner – football player.

- Gabriele Pin (born 1962) – football player and coach.

- Andrea Poli (born 1989) – football player.

- Tommaso Benvenuti (rugby union) (born 1990) – rugby union player.

- Amia Venera Landscape – Post-Metal band.

- Renato Talamini – Italian epidemiologist.

See also

- Battle of Vittorio Veneto

- Order of Vittorio Veneto

- Vittorio Veneto-class battleship

- Cruiser Vittorio Veneto

Twin towns

References

- "Superficie di Comuni Province e Regioni italiane al 9 ottobre 2011". Istat. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- Population data from Istat

- "Historical Maps of Italy: Italy, 1920 (London Geographical Institute)". Edmaps.com. Retrieved 4 December 2017. Vittorio is shown due north of Venice, south of Belluno.

- Ceva, Giulio (2005). Teatri di guerra. Comandi, soldati e scrittori nei conflitti europei (in Italian). Franco Angeli Editore. p. 142. ISBN 8846466802.

- Sergio De Nardi, Giovanni Tomasi: L'agro centuriato cenedese. Studi e ricerche, Vittorio Veneto (in Italian). Dario De Bastiani, 2010, ISBN 978-88-8466-198-2.

- Augusto Lizier and Reginald Francis Treharne, "Ceneda", in Enciclopedia Italiana (in Italian) (1931)

- Histories 2.3

- Vita Sancti Martini 4.668

- Historia Langobardorum 4.28.

- http://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/diocese/dvitt.html

- q.v. Manlio Cortelazzo. Guida di Dialetti Veneti. vol. 1. Padua: Cleop, 1979.

Sources

- Sartori, Basilio (2005). A Ceneda con S. Tiziano Vescovo e i suoi Successori (712-2005). Vittorio Veneto: TIPSE.