Marcantonio Flaminio

Marcantonio Flaminio (winter 1497/98 – February 1550), also known as Marcus Antonius Flaminius, was an Italian humanist poet, known for his Neo-Latin works. During his life, he toured the courts and literary centers of Italy. His editing of the popular devotional work, the "Beneficio di Cristo" illustrated a hope that the Catholic church would move closer to some of the thinking of the protestant reformers.

Marcantonio Flaminio | |

|---|---|

Marcantonio Flaminio. | |

| Born | winter 1497/1498 |

| Died | February 1550 Rome, Italy |

| Pen name | Marcus Antonius Flaminius |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Period | 1515–1549 |

| Literary movement | Renaissance humanism |

| Relatives | Giovanni Flaminio (father) |

Biography

Flaminio grew up in Serravalle, a small village in the Veneto (in the north of Italy). When he was 11, Austria invaded the Veneto, and Marcantonio and his family were forced to flee to his father's native village, Imola, a village south of Bologna. A friendly cardinal gave the family financial support.

In 1514, Flaminio was given the chance to go to Rome to get a broader education. By that time the boy was already "an accomplished scholar, and something of a poet".[1] He was introduced to Pope Leo X, and placed by him under the care of the humanist and poet Raffaele Brandolini. Falconi has suggested that Leo became infatuated with the seventeen-year-old; arranging the best education that could be offered for the time. However, suspicions of Leo's less than honest motives seem to have led to Flaminio's father intervening, and taking the unusual step of declining a certain career in the church as mapped by Leo, in favour of demanding his son return to university at Bologna.[2][3][4][5] That same year, Flaminio also went to Naples, where he met Jacopo Sannazaro. They became close friends, and the latter greatly influenced Flaminio's poetry.

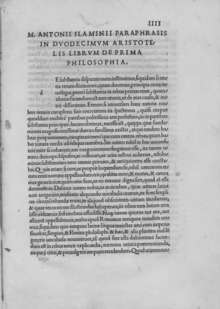

In 1515, Flaminio moved to Bologna, where he dedicated himself to the study of philosophy. His first poems were published that year in a collection consisting of odes, eclogues, epitaphs and Catullan love lyrics. All the poems follow the tradition of Neo-Latin secular verse, taking up the subjects of the famous classical poets (such as Virgil, Ovid, and Catullus). In university, he met new lifelong friends, but after a few years, Bologna begins to bore him.

In 1520, now an adult, he travelled to Padua, to study literature, Aristotelian philosophy, and law, but fell seriously ill with syphilis. He survived, and in the same year, accompanied by his patron Domenico Sauli, he visited Rome to witness the coronation of the new Pope, Clement VII. Rome, by that time, was a place where the plague had free rein, the river Tiber overflowed its banks, and a war was in progress. Maddison says: "…the cardinals had fled, paganism had come into life — an ox was crowned with flowers and sacrificed in the Colosseum…".[1]

In 1524, he met Bishop Giberti of Verona and was taken into his household in 1528, in which he continued to live for the next 14 years. The group of bishops, poets, and scientists within the household were keen to put into practice the ideas of a "reformed church". That year, Flaminio became a member of the Oratorio del Divino Amore, "a group of 60 clerics and laymen who met on Sunday afternoons in the church of Saints Silvestro and Dorotea in Trastevere to discuss theology and to practise spiritual exercises".[1]

From this period on, he became more serious and philosophical. According to Nichols, "He became more and more intensely concerned with religion, devoting himself in particular to the study of the psalms…".[6] He studied Greek, Hebrew and theology and began to read the works of religious reformers.

In 1536, his father died, and Flaminio returned home. When he came back to Rome, he gained the favour of the rich and influential Farnese family, which provided some protection despite his strong and controversial interest in church reform.

In 1538, his health worsened, and he decided to live in Naples. After a year, he visited the Count of Caserta where he remained for over a year. He regained his health and wrote his second book of Lusus Pastorales. During the stay, he became part of several literary circles and notably fell under the influence of the religious group around Juan de Valdes. This group believed that the soul's relation with God was more important than the formal relations with the Church.

In 1541 he moved to Viterbo to form part of Cardinal Reginald Pole's household. Pole was likewise one of the leading figures pushing for reform, and dialogue with the protestant theologians.

In Venice in 1543, the Beneficio di Cristo, "the most popular devotional work in sixteenth-century Italy" was published.[1] The work was heavily influenced by John Calvin's "Institutes" of 1539, and incorporated substantial quotes.[7] It has been described as a "deeply Augustinian work", and stressed throughout man's absolute dependence on Christ for salvation. The first four chapters, in particular, expounded the doctrine of salvation by faith alone (Sola fide). Without faith in God, man is incapable of good works. The book was subsequently condemned by the Inquisition, and Flaminio was thought to have been behind its editing and publication.

In 1545 the Council of Trent was reconvened. Flaminio was offered a secretaryship by the Pope but was forced to decline it (he did so in an elegy to Alessandro Farnese) because of ill health. During this period he did find time to write a poetic paraphrase of several Biblical psalms. In the spring of 1548, he fell seriously ill, suffering from malaria, and died in 1550 in Rome.

During his life, Flaminio was always a purist poet: in his Latin poetry, he referred only to the best classical writers; he specialised in pastoral poems, which were about pure love and nature. This idea also fits with his religious views, which stressed purity and the importance of a personal relationship with God, de-emphasizing the intermediary role of the Church.

Works

In 1515, Flaminio's first collection of poems was published, containing poems in many different genres.

Before his twenties, he also published an edition of a posthumous work of Marullus.

In 1526, he finished his first book (which he started in 1521) of Lusus Pastorales, a collection of bucolic epigrams).

He also wrote an elegy about his syphilis and several other elegies, as well as odes, epigrams, hymns, eclogues and epitaphs (and a large number of letters in various poetic forms to his friends, colleagues and patrons). He paraphrased 32 psalms in prose, and 30 in poetry. He also translated several works from several languages to Latin and Italian. All his Latin poetry has been brought together in a modern collection Carmina, consisting of eight books.

In the last two years of his life he wrote poetic memorials to his friends (about 127 people).

After his death, Flaminio's Carmina Sacra was found and published in 1551. The poems were written in the last few years of his life and are "simple and eloquent religious poems".[6]

References

Sources

- Aldrich, R.; Wotherspoon, G., eds. (2001). Who's Who in Gay and Lesbian History: From Antiquity to the Mid-Twentieth Century. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415159838.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cesareo, G. A. (1938). Pasquino e pasquinate nella Roma de Leone X [Pasquino and lampoons in the Rome of Leo X] (in Italian). Rome.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Falconi, C. (1987). Leone X : Giovanni de' Medici (in Italian). Milan: Rusconi. ISBN 978-8818180084.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fenlon, D. (1973). Heresy and Obedience in Tridentine Italy: Cardinal Pole and the Counter Reformation. CUP. ISBN 978-0521200059.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Maddison, C. (1965). Marcantonio Flaminio, Poet, Humanist and Reformer. London: Routledge.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nichols, F. J. (1979). An Anthology of Neo-Latin Poetry. New Haven: Yale University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pastore, A. (1978). Marcantonio Flaminio, Lettere. Pubblicazioni dell'Istituto di storia medioevale e moderna della Facoltà di lettere dell'Università degli studi di Trieste. 1. Rome: Edizioni dell' Ateneo & Bizzarri.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pastore, A. (1979). "Due bilioteche umanistiche del Cinquecento (I libri del Cardinal Pole e di Marcantonio Flaminio)". Rinascimento. 19: 269–290.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Scorsone, M. (1993). Marcantonio Flaminio, Carmina. Parthenias. Collezione di poesia neolatina (in Latin and Italian). San Mauro Torinese: Edizioni RES. ISBN 978-8885323100.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wagner, T. (1977). Missverstandus un Vuororteil in 'Der Unterdruckte sexus'. Berlin.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- The facsimile of the 1543 Venice edition of the Benefit of Christ (il Beneficio di Cristo) can be viewed beginning on p. 104 of The Benefit of Christ's Death, London/Cambridge, 1855