Umayyad invasion of Gaul

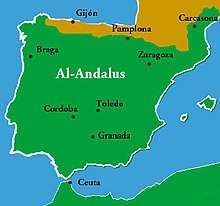

The Umayyad invasion of Gaul occurred in two phases in 720 and 732. Although the Muslim Umayyads secured control of Septimania, their incursions beyond this into the Loire and Rhône valleys failed. By 759 they had lost Septimania to the Christian Franks.

| Umayyad invasion of Gaul | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Early Muslim conquests and the Reconquista | |||||||||||

The Battle of Tours in 732, depicts a triumphant Charles Martel (mounted) facing Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi (right) at the Battle of Tours. Painting (1837) by Charles de Steuben. | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||||

| Andalusi commanders (as of 750) | Septimania | Aquitanians Gascons (Basques) |

Kingdom of the Franks Kingdom of the Lombards | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||||

|

Al-Samh ibn Malik al-Khawlani † Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi † Yusuf ibn 'Abd al-Rahman al-Fihri |

Ardo † Maurontus Ansemund † |

Odo of Aquitaine Hunald I of Aquitaine Waifer of Aquitaine |

Charles Martel Childebrand Liutprand Pepin the Short | ||||||||

The invasion of Gaul was a continuation of the Umayyad conquest of Hispania into the region of Septimania, the last remnant of the Visigothic Kingdom north of the Pyrenees.[1] After the fall of Narbonne, the capital of the Visigothic rump state, in 720, Umayyad armies composed of Arabs and Berbers turned north against Aquitaine. Their advance was stopped at the Battle of Toulouse in 721, but they sporadically raided southern Gaul as far as Avignon, Lyon and Autun.[1]

A major Umayyad raid directed at Tours was defeated in the Battle of Tours in 732. After 732, the Franks asserted their authority in Aquitaine and Burgundy, but only in 759 did they manage to take the Mediterranean region of Septimania, due to Muslim neglect and local Gothic disaffection.[1]

Umayyad conquest of Septimania

By 716, under the pressure of the Umayyad Caliphate from the south, the Kingdom of the Visigoths had been rapidly reduced to the province of Narbonensis (Septimania), a region which corresponds approximately to the modern Languedoc-Roussillon. In 713 the Visigoths of Septimania elected Ardo as king. He ruled from Narbonne. In 717, the Umayyads under al-Hurr ibn Abd al-Rahman al-Thaqafi crossed the Pyrenees for the first time on a reconnaissance mission. The following campaign of conquest in Septimania lasted three years.[2][3] Late Muslims sources, such as al-Maqqari, describe Musa ibn Nusayr (712–714) as leading an expedition to the Rhône at the far east of the Visigothic kingdom, but these are not reliable.[2]

The next Umayyad governor, al-Samh, crossed the Pyrenees in 719 and conquered Narbonne (Arbuna to the Arabs) in that year or the following (720).[2] According to the Chronicle of Moissac, the inhabitants of the city were slaughtered.[4] The fall of the city ended the seven-year reign of Ardo and with it the Visigothic kingdom, but Visigothic nobles continued to hold the Septimanian cities of Carcassonne and Nîmes.[2][3] Nevertheless, al-Samh established garrisons in Septimania (721), intending to incorporate it permanently into al-Andalus.[3]

However, the Umayyad tide was temporarily halted in the large-scale Battle of Toulouse (721), when al-Samh (Zama to the Christian chronicles) was killed by Odo of Aquitaine. In general terms the Gothic Septimania surrendered to the Muslims in favourable conditions for them, allowing the Umayyads to rule the region with the conditioned support of the local population and the Gothic nobles.

In 725, his successor, Anbasa ibn Suhaym al-Kalbi, besieged the city of Carcassonne, which had to agree to give half of its territory, pay tribute, and make an offensive and defensive alliance with Muslim forces. Nimes and all the other main Septimanian cities fell too under the sway of the Umayyads. In the 720s the savage fighting, the massacres and destruction particularly affecting the Ebro valley and Septimania unleashed a flow of refugees who mainly found shelter in southern Aquitaine across the Pyrenees, and Provence.[5]

Sometime during this period, the Berber commander Uthman ibn Naissa ("Munuza") became governor of the Cerdanya (also including a large swathe of present-day Catalonia). By that time, resentment against Arab rulers was growing within the Berber troops.

Raid into Aquitaine and Poitou

Uthman ibn Naissa's revolt

By 725, all of Septimania was under Umayyad rule. Uthman ibn Naissa, the Pyrenean Berber lord ruler of the eastern Pyrenees, detached from Cordova, establishing a principality based on a Berber power base (731). The Berber leader allied with the Aquitanian duke Odo, who was eager to stabilize his borders, and is reported to have married Odo's daughter Lampegia. Uthman ibn Naissa went on to kill Nambaudus, the bishop of Urgell,[6] an official acting on the orders of the Church of Toledo.

The new Umayyad governor in Cordova, Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi, mustered an expedition to punish the Berber commander's insubordination, surrounding and putting him to death in Cerdanya, according to the Mozarabic Chronicler, a just retribution for killing the Gothic bishop.

Umayyad expedition over Aquitaine

Emboldened by his success, he attacked Uthman ibn Naissa's Aquitanian ally Duke Odo, who had just encountered Charles Martel's devastating offensive on Bourges and northern Aquitaine (731). Still managing to recruit the necessary number of soldiers, the independent Odo confronted al-Ghafiqi's forces that had broken north by the western Pyrenees, but could not hold back the Arab commander's thrust against Bordeaux. The Aquitanian leader was beaten at the Battle of the River Garonne in 732. The Umayyad force then moved north to invade Poitou in order to plunder the Basilica of Saint-Martin-de-Tours.

Battle of Poitiers (732)

Odo still found the opportunity to save his grip on Aquitaine by warning the rising Frankish commander Charles of the impending danger against the Frankish sacred city of Tours. Umayyad forces were defeated in the Battle of Poitiers in 732, considered by many the turning point of Muslim expansion in Gaul. With the death of Odo in 735 and after putting down the Aquitanian detachment attempt led by duke Hunald, Charles Martel went on to deal with Burgundy (734, 736) and the Mediterranean south of Gaul (736, 737).

Expansion to Provence and Charles Martel

Still, in 734, Umayyad forces (called "Saracens" by the Europeans at the time) under Abd el-Malik el Fihri, Abd al-Rahman's successor, received without a fight the submission of the cities of Avignon, Arles, and probably Marseille, ruled by count Maurontus. The patrician of Provence had called Andalusi forces in to protect his strongholds from the Carolingian thrust, maybe estimating his own garrisons too weak to fend off Charles Martel's well-organised, strong army made up of vassi enriched with Church lands.

Charles faced the opposition of various regional actors. To begin with the Gothic and Gallo-Roman nobility of the region, who feared his aggressive and overbearing policy.[7] Charles decided to ally with the Lombard King Liutprand in order to repel the Umayyads and the regional nobility of Gothic and Gallo-Roman stock. He also underwent the hostility of the dukes of Aquitaine, who jeopardized Charles' and his successor Pepin's rearguard (737, 752) during their military operations in Septimania and Provence. The dukes of Aquitaine in turn largely relied on the strength of the Basque troops, acting on a strategic alliance with the Aquitanians since mid-7th century.

In 737, Charles captured and reduced Avignon to rubble, besides destroying the Umayyad fleet. Charles' brother, Childebrand, failed however in the siege of Narbonne. Charles attacked several other cities which had collaborated with the Umayyads, and destroyed their fortifications: Beziers, Agde, Maguelone, Montpellier, Nimes. Before his return to the northern Francia, Charles had managed to crush all opposition in Provence and Lower Rhone. Count Maurontus of Marseille fled to the Alps.

Loss of Septimania

Muslims reasserted their authority over Septimania for another 15 years. However, in 752, the newly proclaimed King Pepin, the son of Charles, led a new campaign into Septimania, when regional Gothic allegiances were shifting in favour of the Frankish king. That year, Pepin conquered Nimes and went on to subdue most of Septimania up to the gates of Narbonne. In his quest to subdue the Muslim Gothic Septimania, Charles had found the opposition of another actor, the Duke of Aquitaine. The Duke Waiffer, aware of Pepin's expansionist ambitions, is recorded as attacking him on the rearguard with an army of Basques during the siege of Narbonne.

It was ultimately the Frankish king who managed to take Narbonne in 759, after vowing to respect the Gothic law and earning the allegiance of the Gothic nobility and population, thus marking the end of the Muslim presence in southern Gaul. Furthermore, Pepin directed all his war effort against the Duchy of Aquitaine immediately after subduing Roussillon.

Pepin's son, Charlemagne, fulfilled the Frankish goal of extending the defensive boundaries of the empire beyond Septimania and the Pyrenees, creating a strong barrier state between the Umayyad Emirate and Francia. This buffer zone known as the "Spanish March" would become a focus for the Reconquista.

Legacy

Arabic words were borrowed, such as tordjman (translator) which became drogoman in Provençal, and is still in use in the expression "par le truchement de"; charaha (to discuss), which became "charabia". Some place names were also derived from Arabic or in memory of past Muslim inhabitance, such as Ramatuelle and Saint-Pierre de l'Almanarre (from al-manar i.e. 'the lighthouse').[8]

Notes

- Watson 2003, p. 1.

- Watson 2003, p. 11.

- Collins 1989, p. 45.

- Collins 1989, p. 96.

- Collins 1989, p. 213.

- Collins 1989, p. 89.

- Collins 1989, p. 92.

- Planhol & Claval 1994, p. 84.

Sources

- Bachrach, Bernard (2001). Early Carolingian Warfare: Prelude to Empire. University of Pennsylvania Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collins, Roger (1989). The Arab Conquest of Spain, 710–797. Basil Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-19405-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fouracre, Paul (2013). The Age of Charles Martel. Routledge.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lewis, Archibald R. (1965). The Development of Southern French and Catalan Society, 718–1050. University of Texas Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Planhol, Xavier de; Claval, Paul (1994). An Historical Geography of France. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521322089.

- Watson, William E. (1990). The Hammer and the Crescent: Contacts between Andalusi Muslims, Franks, and their Successors in Three Waves of Muslim Expansion into Francia (PhD thesis). University of Pennsylvania.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Watson, William E. (2003). Tricolor and Crescent: France and the Islamic World. Praeger.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)