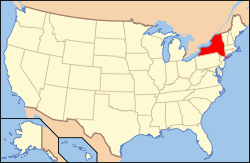

USS California (ACR-6)

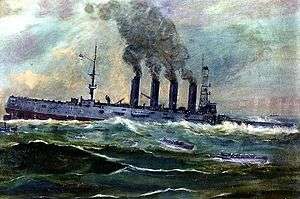

The second USS California (ACR-6), also referred to as "Armored Cruiser No. 6", and later renamed San Diego, was a United States Navy Pennsylvania-class armored cruiser.

USS San Diego (ACR-6), 28 January 1915, while serving as flagship of the Pacific Fleet. Note two-star Rear Admiral's flag flying from her mainmast top. | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: |

|

| Namesake: |

|

| Ordered: | 3 March 1899 |

| Awarded: | 10 January 1901 |

| Builder: | Union Iron Works, San Francisco, California |

| Cost: | $3,800,000 (contract price of hull and machinery) |

| Laid down: | 7 May 1902 |

| Launched: | 28 April 1904 |

| Sponsored by: | Miss F. Pardee |

| Commissioned: | 1 August 1907 |

| Renamed: | San Diego, 1 September 1914 |

| Identification: | Hull symbol: ACR-6 |

| Fate: | sunk 19 July 1918, by U-156 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Pennsylvania-class armored cruiser |

| Displacement: |

|

| Length: | |

| Beam: | 69 ft 6 in (21.18 m) |

| Draft: | 24 ft 1 in (7.34 m) (mean) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | |

| Complement: | 80 officers 745 enlisted 64 Marines |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

| General characteristics (Pre-1911 Refit)[1] | |

| Installed power: | 8 × Modified Niclausse boilers, 12 × Babcock & Wilcox boilers |

| Armament: |

|

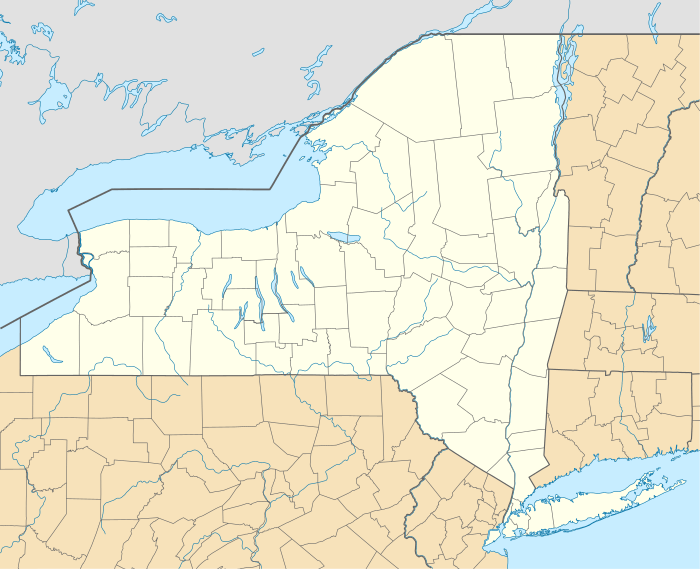

USS SAN DIEGO (Armored Cruiser) Shipwreck Site | |

| |

| Nearest city | Fire Island, New York |

| Area | 27 acres (11 ha) |

| Built | 1918 |

| Built by | Union Iron Works |

| NRHP reference No. | 98000071[2] |

| Added to NRHP | 17 February 1998 |

She was launched on 28 April 1904 by Union Iron Works, San Francisco, California, sponsored by Miss Florence Pardee, daughter of California governor George C. Pardee, and commissioned on 1 August 1907, Captain V. L. Cottman in command.[3]

Service history

Pre-World War I

Joining the 2nd Division, Pacific Fleet, California took part in the Naval Review at San Francisco in May 1908 for the Secretary of the Navy Victor H. Metcalf. Aside from a cruise to Hawaii and Samoa in the fall of 1909, the cruiser operated along the west coast, sharpening her readiness through training exercises and drills, until December 1911, when she sailed for Honolulu, and in March 1912 continued westward for duty on the Asiatic Station. After this service representing American power and prestige in the Far East, she returned home in August 1912, and was ordered to Corinto, Nicaragua, then embroiled in internal political disturbance. Here she protected American lives and property, then resumed her operations along the west coast; she cruised off California, and kept a watchful eye on Mexico, at that time also suffering political disturbance.[3] During that time in Mexico, she was involved in an international incident in which two of her crew were shot and killed.[4]

_by_the_Native_Daughters_of_the_Golden_West%2C_image_taken_from_an_AZO_Tri_2_postcard.jpg)

California was renamed San Diego on 1 September 1914, in order to free up her original name for use with the Tennessee-class battleship California. She served as flagship for Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Fleet, intermittently until a boiler explosion put her in Mare Island Navy Yard in reduced commission through the summer of 1915. The boiler explosion occurred in January 1915 and the actions of Ensign Robert Cary and Fireman Second Class Telesforo Trinidad during the event earned them both the Medal of Honor.[5][6] San Diego after spending time at Guaymas, went on to repair at Mare Island.[7] Afterwards, she served as a popular attraction during the Panama–California Exposition.[8] San Diego returned to duty as flagship through 12 February 1917, when she went into reserve status until the opening of World War I.[3]

World War I

Placed in full commission on 7 April, the cruiser operated as flagship for Commander, Patrol Force, Pacific Fleet, until 18 July, when she was ordered to the Atlantic Fleet. Reaching Hampton Roads, Virginia, 4 August, she joined Cruiser Division 2, and later bore the flag of Commander, Cruiser Force, Atlantic, which she flew until 19 September.[3]

San Diego's essential mission was the escort of convoys through the first dangerous leg of their passages to Europe. Based in Tompkinsville, New York, and Halifax, Nova Scotia, she operated in the weather-torn, submarine-infested North Atlantic safely convoying all of her charges to the ocean escort.[3]

Loss

Early on 18 July 1918, San Diego left the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard bound for New York where she was to meet and escort a convoy bound for France. Her captain — Harley H. Christy — ordered a zigzag course at a speed of 15 kn (28 km/h; 17 mph). Visibility was reported as being from 6–8 mi (9.7–12.9 km). In his report to a Board of Inquiry on the cruiser's loss, Christy stated that all lookouts, gun watches, and fire control parties were at their appointed stations and on full alert, and that all necessary orders to safeguard the watertight integrity of the ship in dangerous waters had been given and were being carried out.[9]

At 11:05 the next day, 19 July, San Diego was steaming northeast of the Fire Island Lightship when an explosion occurred on the cruiser's port side adjacent to the port engine room and well below the waterline. The bulkhead at the site of the explosion was warped so that the watertight door between the engineroom and No. 8 fireroom could not be shut, and both compartments immediately flooded. Captain Christy assumed that the ship had been torpedoed and immediately sounded submarine defense quarters and ordered all guns to open fire on anything resembling a periscope. He called for full speed ahead on both engines and hard right rudder, but was told that both engines were out of commission and that the machinery compartments were rapidly flooding. The ship had taken on a 9° list and water began pouring in through one of the 6-inch (150 mm) gun ports, flooding the gun deck.[9] As water poured into the gun deck it also entered coal chutes and air ducts, further increasing list.[10]

Informed that the ship's radio was not working, Christy dispatched the gunnery officer to the mainland with a boat crew to summon rescue vessels.

About 10 minutes after the explosion, the cruiser began to sink. Orders were given to lower the liferafts and boats. Captain Christy held off giving the order to abandon ship until he was certain that San Diego was going to capsize, when the crew abandoned the vessel in a disciplined and orderly manner. Christy was rescued by a crewman named Ferdinando Pocaroba.[11] She had sunk in 28 minutes with the loss of six lives, the only major warship lost by the United States after its involvement in World War I. Two men were killed instantly when the explosion occurred, a crewman who had been oiling the port propeller shaft was never seen again, a man was killed by one of the smokestacks breaking loose as the ship capsized, one was killed when a liferaft fell on his head, and the sixth was trapped inside the crow's nest and drowned.[12]

Meanwhile, the gunnery officer had reached shore at Point O' Woods, New York after a two-hour trip, and vessels were at once sent to the scene.

The Navy Department was informed that a German minelaying submarine was operating off the east coast of the US and the US Naval Air Service was put on alert. Aircraft of the First Yale Unit, based at Bay Shore, Long Island, attacked what they thought was a submerged submarine lying on the seabed in around 100 ft (30 m) and dropped several bombs; it turned out to be San Diego.

Cause

Captain Christy was of the opinion, following the sinking, that San Diego had been sunk by a torpedo. However, there was no evidence of a U-boat in the area at the time, and no wake of a torpedo was seen by the lookouts. While it was reported that five or six mines had been found in the area, the idea that she had struck a mine was also considered unlikely as it was thought that a mine would have been more likely to detonate at the bow or the forward part of the ship.[13] It was subsequently reported that experienced merchant officers believed that a mine was the probable cause, due to the violence of the explosion and the rapidity with which the ship sank.[14] In August 1918, the Naval Court of Inquiry appointed to investigate the loss of the cruiser concluded that San Diego had been sunk by a mine, mentioning that six contact mines had been located by naval forces in the vicinity of the spot where she had sunk.[15]

In 1999, a theory was advanced that a German spy Kurt Jahnke had planted explosives aboard causing the sinking.[5][16] The claim was contested by the Naval Historical Center.[5]

In July 2018, the United States Navy News Service reiterated that the cause of the sinking of San Diego was still unknown.[17][18] However, the German submarine, U-156 had earlier laid a number of mines along the south shore of Long Island,[19] and the sinking of San Diego was attributed to her.[12][20] Naval records recovered in Germany after the war had shown that U-156 had been operating off the coast of New York, laying mines.[21]

In December 2018, at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union, Alexis Catsambis, an underwater archaeologist with the Navy, stated "We believe that U-156 sunk San Diego".[22][23][24] Flooding patterns studied "weren't consistent with an explosion set inside the vessel", while the hole "didn't look like a torpedo strike." "Torpedoes of the time carried more explosives than mines — and would have shown more immediate damage," stated University of Delaware marine scientist Arthur Trembanis, who took part in the latest wreck study. Mines were anchored at optimal depths to tear open warships, according to Ken Nahshon, another researcher. The mine in question hit an "unguarded lower part of the ship, where the hull was only about a half inch thick", he argued.[25]

Wreck

The wreck presently lies in 110 ft (34 m) of water, with the highest parts just 66 ft (20 m) below the surface, and as a result is one of the most popular shipwrecks in the US for scuba diving. Unfortunately the wreck lies inverted (upside-down) and has decayed over the last century. More scuba divers have died over the years on the wreck than the number of crew killed in its sinking, but this has not diminished its popularity. Nicknamed the "Lobster Hotel" for the abundance of lobsters living there, it is also a home to many kinds of fish. The wreck lies at 40°33′0.36″N 73°0′28.39″W, approximately 13.5 mi (21.7 km) due south of the intersection of Route 112 and Montauk Highway in Patchogue, New York.

The wreck is listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

Legacy

In 2015, a print first engraved in 1915, was issued by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing.[26]

See also

- USS Tennessee (ACR-10) - a US Armored Cruiser lost during World War I before American involvement in 1917.

References

Citations

- "Ships' Data, U. S. Naval Vessels". US Naval Department. 1 January 1914. pp. 24–31. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 9 July 2010.

- "California II (Armored Cruiser No. 6)". Naval History and Heritage Command. 29 June 2015. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- "Alexander St. J. Corrie (U.S.A.) v. United Mexican States" (PDF). Reports of International Arbitral Awards. United Nations. IV: 416–417. 2006.

- Captain George J. Albert. "The U.S.S. San Diego and the California Naval Militia". California State Military Museum. California State Military Department. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- "USS San Diego". Commander Naval Surface Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet. United States Navy. Archived from the original on 22 October 2011. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- Richard W. Crawford (28 May 2013). San Diego Yesterday. Arcadia Publishing Incorporated. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-1-62584-044-8.

- Crawford, Richard (24 August 2008). "Navy's original cruiser San Diego met its demise in World War I". San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- Feuer, A. B. The U.S. Navy in World War I: Combat at Sea and in the Air. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 103–106. ISBN 0-275-96212-1.

- National Geographic Channel, Draining New York City, June 10, 2019

- https://july24jmb.tribalpages.com/tribe/browse?userid=july24jmb&view=0&pid=70&ver=9493#moreinfo_

- Bleyer, Bill. "The Sinking of the San Diego". Newsday. Archived from the original on 13 August 2007. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- "SAN DIEGO'S LOSS STILL UNEXPLAINED" (PDF). New York Times. 20 July 1918.

- "SAN DIEGO'S CREW DIFFER AS TO SINKING" (PDF). New York Times. 21 July 1918.

- "DECIDE MINE SANK CRUISER SAN DIEGO" (PDF). New York Times. 6 August 1918.

- Williamson, David (21 January 1999). "UNC-CH historian, dean discovers German spy sank U.S.S. San Diego". University of North Carolina. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

Sport Diver. September–October 1999. pp. 14–15. ISSN 1077-985X.

Hastedt, Glenn P.; Thornhill, William T. (2011). Spies, Wiretaps, and Secret Operations: A-J. ABC-CLIO. p. 413. ISBN 978-1-85109-807-1. - https://news.usni.org/2018/07/19/35213

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RyFJUjuPP3E

- Feuer, p. 103

- Messimer, Dwight R. (2002). Verschollen: World War I U-boat Losses. Naval Institute Press. p. 124. ISBN 1-55750-475-X.

- https://www.businessinsider.com/ap-scientists-scour-wwi-shipwreck-to-solve-military-mystery-2018-12

- https://www.businessinsider.com/ap-scientists-scour-wwi-shipwreck-to-solve-military-mystery-2018-12

- https://nypost.com/2018/12/13/researchers-say-theyve-solved-the-mystery-of-what-sank-the-uss-san-diego/

- https://www.npr.org/2018/12/11/675661414/mystery-blast-sank-the-uss-san-diego-in-1918-new-report-reveals-what-happened

- "US Navy uncovers mysterious reason warship sunk in World War One". 9 News. Associated Press. Retrieved 15 December 2018.

- "Panama Canal Commemorative USS San Diego Intaglio Print". Bureau of Engraving and Printing. United States Department of the Treasury. 24 March 2015. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

Bibliography

- Alden, John D. American Steel Navy: A Photographic History of the U.S. Navy from the Introduction of the Steel Hull in 1883 to the Cruise of the Great White Fleet. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1989. ISBN 0-87021-248-6

- Friedman, Norman. U.S. Cruisers: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1984. ISBN 0-87021-718-6

- Musicant, Ivan. U.S. Armored Cruisers: A Design and Operational History. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1985. ISBN 0-87021-714-3

- United Nations. Reports of International Arbitral Awards, 1929. Volume IV pp. 416–417.

- Taylor, Michael J.H. (1990). Jane's Fighting Ships of World War I. Studio. ISBN 1-85170-378-0.

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to USS California (ACR-6). |

- Navy photographs of California (ACR-6) at the Library of Congress Web Archives (archived 2014-07-04)

- Photo gallery of USS 'California / San Diego' at NavSource Naval History

- hazegray.org: USS California / San Diego

- USS San Diego Lost at Sea Memorial Unveiled (May 23, 2019), video produced for U.S. WWI Centennial Commission.

- USS San Diego Shipwreck Expo site

- Catalogue of ship's and crew's libraries of the U.S.S. California (1905)