Toxteth

Toxteth is an inner-city area of Liverpool. Toxteth is located to the south of Liverpool city centre, bordered by Aigburth, Canning, Dingle, and Edge Hill.

| Toxteth | |

|---|---|

Toxteth sign on Croxteth Road near Sefton Park, Liverpool | |

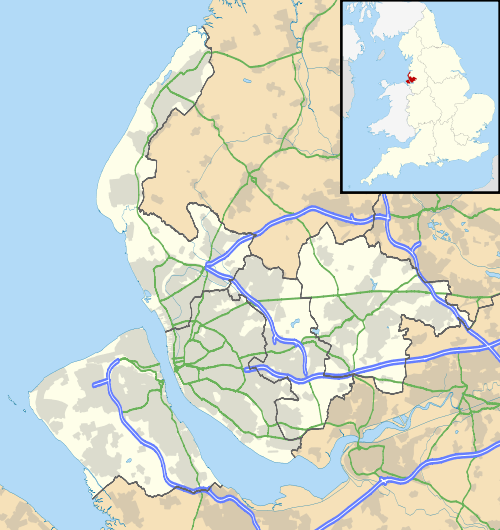

Toxteth Location within Merseyside | |

| OS grid reference | SJ355885 |

| Metropolitan borough | |

| Metropolitan county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LIVERPOOL |

| Postcode district | L8 |

| Dialling code | 0151 |

| Police | Merseyside |

| Fire | Merseyside |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament | |

The area was originally part of a royal park and known as Toxteth Park. It remained predominantly rural up until the 18th century. Toxteth was then developed during this time and into the 19th century, mainly as a residential area to accommodate the increasing working class community centred on Liverpool following the Industrial Revolution. The Welsh Streets in Toxteth were constructed in the mid-19th century to accommodate this demand. Immigration continued into the 20th century, resulting in a significant number of ethnic minority communities in the area.

Toxteth was badly hit by economic stagnation and unemployment in the late 1970s, culminating in riots in July 1981. Although attempts have been made to regenerate the area and improve living standards, significant problems with unemployment and crime remain into the 21st century. Many Victorian properties in the area continue to lie derelict awaiting redevelopment.

Description

The district lies within the borders of the ancient township of Toxteth Park.[1] Industry and commerce are confined to the docks on its western border and a few streets running off Parliament Street. Toxteth is primarily residential, with a mixture of old terraced housing, post-World War II social housing and a legacy of large Victorian houses.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, as Liverpool expanded the ancient park of Toxteth was gradually urbanised. Large Georgian houses were built in the Canning area, followed in the Victorian era by more grand houses, especially along the tree-lined Prince's Road/Avenue boulevard and around Prince's Park. The district quickly became home to the wealthy merchants of Liverpool, alongside a much larger poor population in modest Victorian terraces. Now, some of these streets of terraces are boarded up, awaiting demolition.

Two of the city's largest parks, Sefton Park and Princes Park, are located in or around Toxteth. The earlier Princes Park was laid out by Richard Vaughan Yates around 1840, intending it to be used as open space, funded by the grand houses to be constructed around its edge, as would later happen with Sefton Park. Sefton Park was created by the Corporation of Liverpool in 1872, inspired partly by Birkenhead Park, across the River Mersey. Sefton Park has a large glass Palm House, which contains a statue of William Rathbone V unveiled in 1887, and originally had many other features including an aviary and an open-air theatre.

History

Toponymy

There is some ambiguity as to the origin of the name. One theory is that the etymology is "Toki's landing-place". However, Toxteth is mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086, and at this time, it appears as "Stochestede",[2] i.e. "the stockaded or enclosed place", from the Anglo-Saxon stocc "stake" and Anglo-Saxon stede "place" (found in many English placenames, usually spelled stead).

The Manor

Before the time of the Norman conquest, Toxteth was divided into two manors of equal size. One was owned by Bernulf and the other by Stainulf. After the conquest, part was granted by Count Roger of Poitou to the ancestor of the Earl of Sefton. From this time to about 1604, the land formed part of West Derby forest. The boundaries of the manor are described in the perambulation of 1228 as follows, "'Where Oskell's brook falls into the Mersey; up this brook to Haghou meadow, from this to Brummesho, following the syke to Brumlausie, and across by the old turbaries upon two meres as far as Lombethorn; from this point going down to the "waterfall" of the head of Otter pool, and down this pool into the Mersey.[2] " In 1327, Toxteth was granted to Henry, Earl of Lancaster.

Over the years, various leases and grants were made and the park was owned by Adam, son of William de Liverpool, in 1338. In 1385, William de Liverpool had licence "to take two cartloads of gorse weekly from the park for 12d. a year rent." In 1383 a grant was made to William Bolton and Robert Baxter, in 1394 the lease was resigned and handed over to Richard de Molyneux. The park finally came into the hands of Sir Thomas Stanley in 1447. The parkland descended within the Stanley family until 1596, when it was sold by William Stanley, Earl of Derby, to Edmund Smolte and Edward Aspinwall. In 1604, the Earl sold it to Richard Molyneux of Sefton at a cost of £1,100. The estate descended from this time until 1972 with the death of the 7th Earl.[2]

Toxteth Park

The ancient township of Toxteth contains the village of Smeedon or Smithdown. It stretches over an area of three miles along the River Mersey and two miles inland, the highest point being on the corner of Smithdown Lane and Lodge Lane. A brook ran from the northern end of the area, near the boundary of Parliament Street, where it was used to power a water wheel before it ran into the river. Along the river are two creeks; the one near the middle is known as Knot's Hole, and another further south, called Dickinson's Dingle, received a brook which ran past the east end of St Michael's Church, Aigburth.[2]

At some time in history the creeks were filled in. The Dingle is now in the area where the old northern creek was situated, and St Michael's Hamlet is situated around the southern creek. Outside the southern boundary of the area lies the creek known as Otterspool, which formed the boundary between Wavertree and West Derby. The major road through the area was Park Lane, now Park Place and Park Road. The road ran from the Coffee House, which stood near Fairview Place, down towards the Dingle, and the "Ancient Chapel of Toxteth".[2]

Toward the end of the 16th century, the royal park ceased to be and Puritan farmers from Bolton settled in the area. Setting up 25 farms on land outside Church of England control, which became Toxteth Village, these Dissenters worshipped at the "Ancient Chapel" on Park Road, now known as the Toxteth Unitarian Chapel (not to be confused with Ullet Road Unitarian Church, in Toxteth, south Liverpool). In 1611, they built a school at the Dingle, appointing Richard Mather as schoolmaster. Some years later, he began preaching to the local farmers in the chapel.[3]

In 1796, the Herculaneum Pottery was established on the site of an old copper works. The site later became Herculaneum Dock, which was filled in during the 1980s.

Smithdown

Smithdown, referred to as Esmedune in the Domesday Book, and variously as Smededon, Smeddon, Smethesdune, Smethedon, Smethdon, Smethden,[2] has been merged into Toxteth Park since the granting of the Liverpool Charter in 1207. The definite boundaries of Smithdown have never been fully recorded, but the name continued in use from 1207 until the 16th century, although it is thought to have reached from Lodge Lane to the eastern boundary of Toxteth Park. In 1066, Smithdown was held as a separate manor, by Ethelmund. During the reign of King John the Manor of Smithdown was taken from its owner, and the king gave him Thingwall instead.

Second World War

During the Second World War, the Free French 13th Demi Brigade of the French Foreign Legion were stationed in Toxteth. On 30 August 1940, the Demi Brigade departed Liverpool for operations against Vichy forces that would include the abortive Battle of Dakar and the storming of Libreville.

Places of worship

As the area began to develop and become more urbanised, several places of worship were built to serve the growing community. The first church was St James's, in 1774. Other churches built during the 19th century include St Patrick's, 1827; St John the Baptist's, 1832; St Thomas's, 1840; St Barnabas's, 1841; St Clement's Windsor, 1841; St Matthew's, 1847; St Paul's, 1848; Holy Trinity, 1858; St Silas's, 1865; St Cleopas's, 1866; St Margaret's, 1869; Christ Church, 1870; St Philemon's, 1874; Our Lady of Mount Carmel, 1878; All Saints', 1884; St Gabriel's, 1884; St Agnes's, 1884; St Bede's, 1886; and St Andrew's, 1893;.[2]

In addition, the following may be considered landmarks: the Welsh Presbyterian Church, nicknamed "Toxteth Cathedral", 1868; the Ullet Road Unitarian Church, 1899, "one of the most elaborate Non-conformist ensembles in the country";[4] the Church of St. Agnes and St. Pancras, also in Ullet Road; the Church of St Clare on the corner of Arundel Avenue and York Avenue, and the Princes Road Synagogue, 1874, "impressively combining Gothic revival and Moorish revival architecture". The Al-Rahma Mosque on Hatherley Street opened in 2008.

Politics

Politically, Toxteth is within the parliamentary constituency of Liverpool Riverside. In the 2019 United Kingdom general election, Kim Johnson of the Labour Party, was elected the Member of Parliament. The council ward is Princes Park, and has three Labour councillors.

Demographics

Immigration to Toxteth has taken place from the 19th century with the arrival of African and Chinese sailors and thousands of Irish Catholic and Welsh migrants, to the present day, most recently from the Caribbean, Yemen and Somalia with relatively few from the Indian sub-continent. The area has a very large community of mixed ethnicity as a result.

Unrest and crime

After the end of World War II, Toxteth became a popular destination for Commonwealth immigrants who arrived in Liverpool from the West Indies and the Indian subcontinent.

However, the economic decline of Britain during the 1970s and early 1980s hit Toxteth and most of the rest of Liverpool particularly hard, leaving it with some of the highest unemployment rates in the country. Crime increased as a result. The standard of housing in both the public and private sector also declined, which would lead to eventual widespread demolition and refurbishment.

July 1981 saw riots in which dozens of young males clashed with police, resulting in numerous injuries on both sides as well as extensive damage to properties and vehicles. Poverty, unemployment, racial tension, racism and hostility towards the police were largely blamed for the disturbances, which were among the worst scenes of unrest seen during peacetime in Britain. Hundreds of people were injured, one man was killed by a police Land Rover, and numerous buildings and vehicles were damaged. This wave of rioting was perhaps the most prominent of a series of riots which other inner city areas during the spring and summer of 1981 - Brixton in London being the scene of another similarly violent riot.[5]

A second, less serious riot occurred in Toxteth on 1 October 1985. However, this was largely overshadowed the riots which occurred that autumn in the Handsworth area of Birmingham and the Tottenham area of London.[6]

As well as racial and civil unrest, vehicle crime has also blighted Toxteth since around 1980. A notable tragedy occurred in Toxteth on 30 October 1991, when two children (nine-year-old Daniel Davies and 12-year-old Adele Thompson) were fatally injured by a speeding sports car driven by 18-year-old joyrider Christopher Lewin in Granby Street. Lewin was found guilty on a double manslaughter charge at Liverpool Crown Court on 24 September 1992 and sentenced to seven and a half years in prison, as well as being banned from driving for seven years. At the end of his trial, relatives and friends of the two victims pelted him with missiles and threatened to attack him. Five of them were ejected from the court.[7]

With Toxteth still fresh in the mind of the British media and public a decade after the 1981 riots, it was reported in the international media during December 1991 that the area still suffered from many of the problems that were said to have triggered the original riots, and some local residents claimed that things had gone from bad to worse. Despite the efforts of community groups and other services to help train young people for jobs, youth unemployment in the area was reported to be above 50%.[8] In April 1994, The Independent newspaper highlighted that Toxteth was still one of the most deprived areas in Britain, with unemployment in some districts exceeding 40%, with theft, drug abuse and violent crime being rife.[9]

A third wave of rioting broke out in Toxteth on the evening of 8 August 2011 at a time when riots flared across England, although again this wave of rioting was overshadowed by worse riots in Birmingham and London. Vehicles and wheelie bins were set alight in the district, as well as in nearby Dingle and Wavertree, and a number of shops were looted as well. Two police officers suffered minor injuries as a result of the rioting. It was brought under control in the early hours of the following morning.[10] Individuals arrested and charged in relation to the 2011 rioting were from addresses all across the city, with Toxteth residents being a clear minority. However, as had been the case in 1991, it was rioting various districts of London rather than Liverpool which were most notably affected by this wave of national rioting, once again at a time when unemployment and social unrest were high as a result of a recession.[11]

Regeneration

Much of the area continues to suffer from poverty and urban degradation. House prices reflect this; in summer 2003, the average property price was just £45,929 (compared to the national average of £160,625).

Despite government-led efforts to regenerate Toxteth after the 1981 riots, few of the area's problems appeared to have improved by 1991, by which time joyriding had also become a serious problem; on 30 October that year, a 12-year-old was killed by a speeding stolen car on Granby Street, seriously injuring a nine-year-old who died in hospital from his injuries six days later.[12]

By the time of the riot's 20th anniversary in July 2001, it was reported that many of the issues which contributed to the riots were still rife; not least unemployment and racial tension, as well as a decline in the sense of community in some neighbourhoods. Urban dereliction and gun crime remained a significant problem. However, there had already been some significant improvements by this stage, including the rebuilding of the Rialto complex (which was destroyed in the 1981 riot)[13] as a mix of retail, residential and commercial properties.[14]

Housing in Toxteth tends to be in terraces but there is a growing number of flats available as larger Victorian properties are broken up into separate dwellings. This is particularly the case in Canning, and around Princes Park.

Extensive regeneration has taken place in Toxteth over the last few years, including demolition of many of the Victorian terraces in the area. This has created much new development but also scarred the area with cleared sites and derelict streets. There has been strong local opposition to demolition of the Granby Triangle and the Welsh Streets, attracting extensive coverage in the national media and ultimately the Granby Four Streets were removed from the clearance plans. In 2015 a community regeneration initiative which involved a collaboration between a Community Land Trust, Steinbeck Studios and the artists collective Assemble was nominated for the Turner Prize.[15] The prize was awarded to Assemble in December 2015.[16]

Welsh Streets

By 1850, over 20,000 Welsh builders worked in Liverpool who required housing and land in Toxteth was leased for housing development.[17] The Welsh Streets were designed by Richard Owens[18] and built by David Roberts, Son and Co.[19] Through this collaboration, Owens designed over 10,000 terraced houses in the city of Liverpool, particularly those in the surrounding Toxteth area where the Welsh Streets are located.[20] The streets were named after Welsh towns, valleys and villages and were built for Welsh migrants, by Welsh builders. Musician Ringo Starr was born in 9 Madryn Street, where he lived until the age of 4 before moving to Admiral Grove.[21]

Council survey data published in 2005 showed the Welsh Streets were broadly popular with residents and in better than average condition, but were condemned for demolition because of a perceived 'over-supply' of 'obsolete' terraced houses in Liverpool. The proposals have divided the local community.[22] Following unsuccessful demolition plans in 2013, Voelas Street was the first in 2017 to be fully refurbished and offered for rent to tenants. Popularity of the scheme would determine whether further regeneration of the other streets would be undertaken.

Parks

Toxteth has two parks within its borders:

- Sefton Park, one of the last remnants of the royal hunting park. The park was designed by French landscape architect Édouard André.

- Princes Park, first major park created by Joseph Paxton.

Landmarks

- Al Rahma Mosque

- Belvedere Academy

- Church of St. Agnes and St. Pancras, Toxteth Park also in Ullet Road

- Church of St Clare on the corner of Arundel Avenue and York Avenue

- Church of St James, Liverpool

- Florence Institute

- Princes Road Synagogue

- Toxteth Unitarian Chapel

- Welsh Streets

Demolished/former landmarks

Transport

Rail

The local railway station is Brunswick, located on Sefton Street in the south-western extremity of the district. The station is on the Northern Line of the Merseyrail network with trains departing to Southport via Liverpool city centre and to Hunts Cross.

St. James Station is a disused railway station in Toxteth. It was located at the corner of St. James Place and Parliament Street, on the Merseyrail Northern Line. This station is in a deep cutting, cut into the Northern Line tunnel, being in effect an underground station with no roof. It was closed in 1917 as being too near to the terminus at Liverpool Central High Level railway station. Liverpool City Region Combined Authority announced in August 2019 that they were planning to use part of a £172m funding package to reopen the station, subject to the plans being approved.[23] The station is well located to serve the Liverpool Echo Arena at King's Dock and Liverpool Cathedral.

Sefton Park railway station, another disused station, was located at Smithdown Road and Garmoyle Road in nearby Wavertree. The station was closed to passengers in 1960.[24] The station is on the West Coast Main Line Spur with Merseyrail trains running through from Liverpool South Parkway and Lime Street stations.

Buses

Toxteth is well served with bus routes.

Notable residents

- Jean Alexander, actress

- Victor Anichebe, footballer

- Akinwale Arobieke, muscle-feeler

- Arthur Askey, comedian and actor

- Reginald Bevins, Member of Parliament

- Stanley Boughey, recipient of the Victoria Cross

- Eddie Braben, comedy writer and performer

- Wally Brown CBE, teacher

- Ian Callaghan, footballer

- William Connolly (VC), soldier

- Alex Cox, filmmaker

- Alicya Eyo, actress

- Robbie Fowler, football player

- Billy Fury, singer

- Howard Gayle, football player

- Niall Griffiths,

- Jeremiah Horrocks, astronomer

- Holly Johnson, singer[25]

- Curtis Jones, footballer

- James Larkin, trade union leader and activist

- Fred Lawless, writer and playwright

- Gerry Marsden, musician[26]

- George Melly, jazz and blues singer, critic and writer

- Mark Moraghan, actor

- Nikita Parris, footballer

- Wes Paul, guitarist and singer

- Alan Reid, Australian journalist[27]

- Willy Russell, writer and playwright

- Herbert Samuel, politician

- Michael Showers, gangster

- Margaret Simey, political and social campaigner

- Hetty Spiers, screenwriter and author

- Ringo Starr, musician

- Allan Ivo Steel, cricketer

- Ronald Stuart, recipient of the Victoria Cross

- Catherine Walters, courtesan

- Curtis Warren, criminal

- Laurence Westgaph, social historian and activist

References

- Griffiths, Robert (2001). The History of the Royal and Ancient Park of Toxteth. Liverpool Libraries & Information Service. ISBN 978-0902990173.

- 'Townships: Toxteth Park', A History of the County of Lancashire: Volume 3 (1907), pp. 40-5, British History Online, retrieved 29 October 2006

- The Ancient Chapel of Toxteth, The Liverpolitan, August 1948, retrieved 29 October 2006

- The church and the attached church hall have been separately designated by English Heritage as Grade I listed buildings.Historic England. "Unitarian Chapel, Liverpool (1218227)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- "Toxteth riots remembered". BBC News. 4 July 2001.

- "1985: Riots erupt in Toxteth and Peckham". BBC News. 1 October 1985.

- "Angry scenes as joyrider jailed for child deaths". The Independent. London. 25 September 1992.

- SMITH, HELEN (22 December 1991). "Decaying Liverpool No Better Off Than During '81 Riots : England: Spotlight shifts to disenchanted youths who joy ride in stolen cars" – via LA Times.

- "No-Go Britain: Where, what, why". 17 April 1994.

- "Riots: Violence flares in Liverpool for up to five hours". BBC News. 9 August 2011.

- "Update: Details of those charged in connection with the violent disorder". Merseyside Police. 2 December 2011. Archived from the original on 4 April 2012.

- Smith, Helen (22 December 1991). "Decaying Liverpool No Better Off Than During '81 Riots : England: Spotlight shifts to disenchanted youths who joy ride in stolen cars". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- "Toxteth's long road to recovery". BBC News. 5 July 2001. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- "Rialto". Halsall Lloyd Partnership. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012.

- Gallagher, Paul (24 September 2015). "Residents of Granby Four Streets in Toxteth celebrate Turner Prize nomination for community regeneration project". The Independent. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- "Liverpool houses win Turner Prize". 7 December 2015 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- "History of Toxteth's terraced streets is the focus of new BBC documentary". Liverpool Echo. 26 May 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- "Glyndŵr University academic backs bid to save Liverpool's historic Welsh Streets". Glyndŵr University. 29 June 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- Carr, Dr. Gareth. "The Welsh Builder in Liverpool" (PDF). Liverpool Welsh. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- Toner, Christine (23 February 2018). "The Welsh Connection: How Wales has helped shape Liverpool". YM Liverpool.

- Clover, Charles (19 September 2005). "Ringo Starr's old house to be taken down and stored as 11 streets are demolished". The Telegraph. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- Gabriel, Clare (20 May 2005). "City's Welsh streets face threat". BBC News. Retrieved 2 February 2009.

- Tyrrell, Nick (30 August 2019). "Merseyside set to get two new train stations and replacement ferries". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "Disused Stations: Sefton Park Station". www.disused-stations.org.uk.

- Bradbury, Howard (30 October 2014). "Celebrity Interview - Holly Johnson". Cheshire Life. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- Johnson, Mark (11 September 2014). "Liverpool pop legend Gerry Marsden 'on the mend' after illness".

- Holt, Stephen (2012). "Alan Douglas Reid". Australian Dictionary of Biography. 18. Melbourne University Press. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 15 July 2018 – via National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

Bibliography

- Liverpool District Placenames, Henry Harrison 1898

- Liverpool 8, John Cornelius 2001

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Toxteth. |