Tilehurst

Tilehurst /ˈtaɪlhɜːrst/ is a suburb of the town of Reading in the English county of Berkshire. It lies to the west of the centre of Reading, and extends from the River Thames in the north to the A4 road in the south. The suburb is partly within the boundaries of the Borough of Reading and partly in the district of West Berkshire. The part within West Berkshire forms part of the civil parish of Tilehurst, which also includes the northern part of Calcot and a small rural area west of the suburb. The part within the Borough of Reading includes the Reading electoral ward of Tilehurst, together with parts of Kentwood and Norcot wards.

| Tilehurst | |

|---|---|

Tilehurst Triangle | |

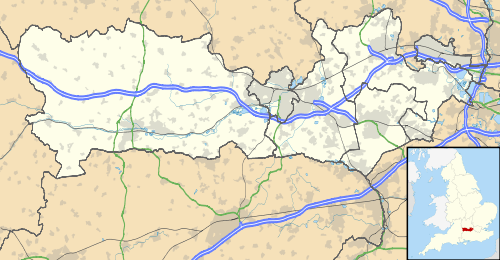

Tilehurst Location within Berkshire | |

| Population | 14,683 United Kingdom Census 2001 14,064 (2011 Census)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SU667736 |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | READING |

| Postcode district | RG30, RG31 |

| Dialling code | 0118 |

| Police | Thames Valley |

| Fire | Royal Berkshire |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| UK Parliament | |

History

Tilehurst was first recorded in 1291, when it was listed as a hamlet of Reading in Pope Nicholas III's taxation.[2] At this time, the settlement was under the ownership of Reading Abbey, where it stayed until the Dissolution of the Monasteries.[2] Tilehurst became an extensive parish, which included the tything of Theale as well as the manors of Tilehurst, Kentwood, Pincents and Beansheaf.[2]

In 1545, Henry VIII granted the manor of Tilehurst to Francis Englefield, who held it until his attainder (and forfeiture of the manor) in 1586.[2] The following year, Elizabeth I gave the manor to Henry Forster of Aldermaston and George Fitton. Forster and Fitton possessed the manor until the turn of the century, when Elizabeth sold it to Henry Best and Francis Jackson.[2] Over the space of five years, the manor passed from Best and Jackson to the son of Sir Thomas Crompton, then on to Dutch merchant Peter Vanlore.[2] Vanlore built a manor house on the estate—Calcot Park. Throughout the 17th century the manor passed through the Vanlore family to the Dickenson family, before being purchased in 1687 by the Wilder family of Nunhide (builders of Wilder's Folly) for £1,075.[2] Page and Ditchfield write that in the early 18th century the manor was also owned by the family of John Kendrick, albeit for a short period.[2]

The manor subsequently passed to Benjamin Child, who married Mary Kendrick,[5] heir of the Kendrick family.[2] After Kendrick's death, Childs sold the manor to descendants of John Blagrave in 1759.[2] The Blagrave family built the present-day Calcot House, which—according to one story—was made necessary by Child's eviction.[6] After Child sold the estate to the Blagraves, he was reluctant to leave the house.[6] The Blagraves were forced to remove the building's roof to "flush" him out of the building, thereby requiring a new building to replace the uninhabitable original house.[6][7] The manor was retained by the Blagrave family until the 1920s, after which it served as the clubhouse for the estate's golf course and was later converted into apartments.

The manor of Kentwood was owned by Peter Vanlore, before passing through the Kentwood family (taking their name from the manor itself), the Swafield family, the Yate family, the Fettiplace family and the Dunch family.[2] In 1719, the manor was divided between heirs.[2] The manor of Pincents was named after the local Pincent family. Originally from Sulhamstead, the family owned the manor until the end of the 15th century.[2] After this it was owned by the Sambourne family before they sold it to the Windsor family. In 1598 the manor was sold to the Blagrave family; its succession through the family is identical to that of Calcot Park.[2] In the 1920s the manor was sold off and later became a wedding and conference venue. The manor of Beansheaf took its name from a 13th-century Tilehurst family. In 1316 John Beansheaf granted some of the manor's land to John Stonor.[2] While it is not recorded how much was granted, it is likely that Stonor inherited the entire estate as the Beansheaf name did not appear in subsequent records.[2] In 1390, Ralf Stonor gave the manor to William Sutton of Campden and John Frank. Frank later returned his share of the manor to Ralf Stonor, after which the manor was retained by the Stonor family until the end of the 15th century. The manor left the Stonor family when John Stonor died with no heirs. It passed through his sister, Anne, to her husband—Adrian Fortescue.[2] Some of the manor was later reinherited by the Stonors, though the majority was retained by the Fortescues until passing through marriage to the Wentworth family.[2] In 1562 the manor was bought by John Bolney and Ambrose Dormer, after which it was passed into the family of Tanfield Vachell.[2] The manor was inherited by the Blagrave family some time after 1600.[2]

Throughout the 19th century, a number of changes came to Tilehurst. A national school was founded in 1819 to provide education to children not in private schooling.[8] Theale became a separate ecclesiastical parish in 1832,[2] and a separate civil parish in 1894.[9] The Great Western main line was built through Berkshire in 1841; Tilehurst's railway station opened in 1882.[8]

By 1887, the boundaries of Reading included parts of Tilehurst.[10] In 1889 a large part of the parish was transferred to Reading, and further areas were transferred to the borough of Reading in 1911.[9]

In the 1920s and 30s, many new houses—particularly semi-detached residences—were built in Tilehurst. This gave the need for improved utilities; electricity arrived in the 1920s (replacing the gas that fuelled the area from 1906) and a new water tower was built in 1932.[8] After World War II, Tilehurst—like many other settlements—was in need of new housing; from 1950 many houses and estates were built in the area.[8]

In the mid-1960s a prominent Victorian character property, Westwood House with some 5 acres of open grounds was demolished as part of the ever pressing need for new housing. This site was positioned between Westwood Road and Pierce's Hill and had served well as a venue for occasional local social events.

Toponymy

The name Tilehurst comes from the Old English "tigel" meaning "tile" and "hurst" meaning "wooded hill".[11][12][13] Alternative spellings have included Tygelhurst (13th century), Tyghelhurst (14th century), and Tylehurst (16th century). The present spelling became commonplace in the 18th century.[8]

Governance

Tilehurst is divided between the civil parish of Tilehurst in the district of West Berkshire[14] and the electoral wards of Tilehurst[15] and Kentwood (where Tilehurst railway station is located) in the unitary authority of Reading.

Education governance in Tilehurst is split between West Berkshire Council and Reading Borough Council as their boundaries run through the suburb.[16]

The parish is split between four churches—those of St Catherine, St George, St Mary Magdalen and St Michael.[17]

Geography

Tilehurst is situated on a hill (approximately 100 metres (330 ft) AMSL), 3 miles (4.8 km) to the west of Reading.[18] The land is steep to the west and south of the village; the gradient is smoother north (towards the River Thames) and east (descending towards Reading).[18]

Much of Tilehurst was enclosed common land during the 18th and 19th centuries; as this land was developed with housing the commons were lost. Arthur Newbery Park is a surviving area of commonland. Similarly, Prospect Park was enclosed and established before major development of the area was undertaken.

Tilehurst is bordered to the west by wood and farmland, to the north by other settlements (such as Purley on Thames and the river itself), to the east by Reading, and to the south by the Reading to Taunton line, the M4 motorway and the River Kennet.[18]

Tilehurst is centred around Tilehurst Triangle (known locally as "the village"), a pedestrianised area providing shopping, leisure and educational facilities.[8][18] Other areas of Tilehurst include Kentwood near the railway station in the north, Norcot in the east, Churchend around St Michael's parish church in the south, and Little Heath in the west.

Tilehurst has a site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) just to the west of the village, called Sulham and Tidmarsh Woods and Meadows.[19]

Tilehurst has four local nature reserves called Blundells Copse, Lousehill Copse, McIlroy Park & Round Copse.[20][21]

Demography

Tilehurst ward (Reading)

The 2011 census recorded 9,155 residents in the ward and an area of 2.10 square kilometres (0.81 sq mi).[22]

Tilehurst parish (West Berkshire)

In the 2001 census there were 14,683 residents of the parish.[23]

Economy

Until the late 19th century, the majority of working men in Tilehurst were employed in farming or similar agricultural work.[8] The main industry associated with Tilehurst, however, was the manufacture of tiles. This industry present in the district until recent times; the 1881 UK census listed a number of men as being employed as brickmen in kilns in the area.[8] Written evidence of brickwork can be traced to the 1600s, but with the peak of production at around 1885. Kilns were established at Grovelands and Kentwood—both to the east of the settlement—with clay pits being dug on Norcot Hill in an area now known as The Potteries.[8] An overhead cable was used to transport the clay-filled buckets between the pits and the kiln across Norcot Road;[8][24] this was shown on a 1942 map of the area as an "aerial cable" running from the clay pit in Kentwood to Grovelands works approximately 1.5 miles (2.4 km) away.[25] The cable was also included on the 1940s Ordnance Survey New Popular Edition maps, labelled as an "aerial ropeway".[26] An 1883 Ordnance Survey map of Berkshire shows a number of kilns in the Grovelands area (on the present-day Colliers Way estate)[27] and one in Norcot near the present-day Lawrence Road.[28] The latter was more specifically named in the 1899 Pre-WWII 1:2,500 scale Berkshire map as "Norcot Kiln, Brick and Tile Works". By the 1920s, Tilehurst Potteries had been formally established at Kew Kiln on Kentwood Hill.[29][30]

By the 1960s, clay business had waned and the pits were closed in 1967.[8][24]

Architecture

The architecture of Tilehurst ranges from 19th century thatched cottages[8] to late 20th-century housing estates. Victorian and Edwardian terraces[31] (built using bricks from the Tilehurst kilns) are common in the area; streets such as Blundells Road and Norcot Road display this type of architecture.[32][33] As the area expanded, a huge number of semi-detached dwellings were built in the mid-20th century,[31][34] in areas such as St Michael's Road (1930s)[34] and on the Berkshire Drive estate (1950s).[35]

Examples of unique architecture in Tilehurst include two water towers: Tilehurst Water Tower—a 1932 concrete building, open octagonal in design with arcading supporting a cylindrical drum,[8][36] and Norcot Water Tower—an 1890s brick building with tiered blind arcading.[36] The Mansion House in Prospect Park (19th century) is a regency mansion built in Portland stone.[37] The north and south faces feature Doric and Ionic order porticos respectively.[37]

Culture

Tilehurst has a horticultural society[38] which holds a produce show annually in August.[38][39]

The village has few establishments for performing arts, as most are provided in Reading. An amateur dramatics society, the Triangle Players, is based in the village.[40] A branch of the Allenova School of Dancing is also situated in Tilehurst.[41] Tilehurst Square Dance Club draws dancers from Reading and beyond and has been operating since 1989.[42]

Transport

Tilehurst railway station is located at the northern edge of Tilehurst. It has regular Great Western Railway services between Reading and Oxford on the Great Western Main Line, and commuter services to London Paddington. Journey times are approximately five minutes to Reading and 35 minutes to Oxford.[43] Connections to the south and south-west via the Reading to Taunton Line and the Reading to Basingstoke Line are made by services changing at Reading.

Reading Buses services 15, 15a, 16, 17, 28, 33, serve Tilehurst,[44] connecting the village to Reading, Purley and Pangbourne.[44]

Tilehurst is bordered by two major roads—to the north by the A329 (connecting the village to Reading and Pangbourne), and to the south by the A4 (connecting the village to Reading and Theale).[18] Non-arterial roads in Tilehurst saw a great improvement in the 1940s with the introduction of trolleybuses in Reading.[45]

Education

Tilehurst is served by two comprehensive secondary schools—Denefield School[46] and Little Heath School.[47] The catchment areas of Prospect School and Theale Green Community School also cover parts of Tilehurst.[48]

Tilehurst is served by Brookfields School, a special school catering for students with moderate, severe or profound and multiple learning difficulties.[49]

Primary education in Tilehurst includes Birch Copse Primary School, Downsway Primary School, English Martyrs' Catholic Primary School, Moorlands Primary School, Park Lane Primary School, Ranikhet Primary School, St Michael's Primary School, St Paul's Catholic Primary School, Springfield Primary School, Meadow Park Academy, Westwood Farm Infant School, and Westwood Farm Junior School.[50]

Places of worship

Tilehurst has a number of religious buildings covering numerous denominations. The Church of St Michael, situated centrally in the parish, is a brick church with a square tower.[11] Parts of the building date from the 13th century,[51] replacing an earlier church thought to have been built in 1189.[51] Sir Peter Vanlore is buried in the church's Lady chapel.[52]

The Anglican church of St Catherine of Siena was built in the Little Heath area of Tilehurst from 1962 to 1964.[53] A Methodist church is near the village centre,[54] and a Latter-day Saints church opened in Tilehurst in the 1970s.[8] The Roman Catholic church of St Joseph was built in Park Lane from 1955–56.[55] Tilehurst also has a United Reformed Church[56] (built on the site of an early 19th-century Congregational Chapel[8]), a Bethel United Church,[57] and Anglican churches dedicated to St George and St Mary Magdalen.[57]

Tilehurst does not have any synagogues, mosques or gurdwaras. The nearest are in West Reading,[58] central Reading[59] and East Reading respectively.[60]

Sport

Tilehurst has been represented in numerous sports for over a century. Tilehurst Cricket Club existed from at least 1883.[61] The club originally played on Church End Lane. While the exact location of the ground is unknown, it is likely that it was on a recreation ground behind the present-day Moorlands School.[62] Victoria Recreation Ground was established in 1897, and the cricket club began using the new park as their ground at some point after this.[63] The club joined the Reading and District Cricket League in 1900; the Reading Chronicle reported on the club's first game—a loss to nearby Grovelands CC—by saying "Tilehurst were but poorly represented, several of their best players not having signed the required fourteen days, and they had to play ten men only".[62] Tilehurst joined the newly formed Hampshire League in 1973, proving successful in their first two seasons.[62] Between 1991 and 1996, Tilehurst played in the Berkshire League. The following year, Tilehurst CC merged with Theale CC to form Theale and Tilehurst Cricket Club. The reason for the merger is attributed to Theale's lack of players but good facilities, and Tilehurst's surplus of players but lack of facilities.[62] The club now play at Englefield Road, Theale, in the Thames Valley Cricket League.[62]

Tilehurst is represented by three football teams Barton Rovers,[64] Tilehurst Panthers[65]and Westwood Wanderers. Barton Rovers, established in 1982, are based at Turnham's Farm, Little Heath.[66] Tilehurst Panthers, established in 2006, are a ladies team based at Denefield School and the Cotswold Sports Centre in Tilehurst.[67] Westwood Wanderers were established in 1972 and are a men's team based at the Cotswold Sports Centre. The team play their home matches at Denefield School.

Reading Racers were based at Reading Greyhound Stadium from 1968 until the stadium's demolition in 1975.[68] The team then moved to Smallmead Stadium, south of Reading.[68]

Notable residents

- Bryan Adams, musician, lived in Tilehurst in the 1960s while his father was stationed in the UK[69]

- Jacqueline Bisset, actress, grew up in Tilehurst in a 17th-century country cottage, where she now lives part of the year

- Kenneth Branagh, actor, attended Meadway School in the 1970s[70]

- Tim Dinsdale, searcher for the Loch Ness Monster.[71]

- Mike Oldfield, musician, grew up in Tilehurst[72]

- Ayrton Senna, Formula 1 driver, lived on the Pottery Road estate in the 1980s[73]

- Sir Peter Vanlore (1547-1627) bought Tilehurst Manor and lived there with his wife Lady Jacoba van Loor (daughter of Henri Thibault). Sir Peter was a well respected trader and merchant during the Elizabethan and early Stuart eras. Sir Peter was born in Uttrecht, the Netherlands. Sir Peter and his wife had several children; one of whom was Anna van Loor whom married the Dutch jeweller and lawyer, Sir Charles Caesar ( formerly Cesarini - Adelmare ).

References

- "Civil Parish population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- P.H. Ditchfield; William Page, eds. (1923). "Parishes: Tilehurst". A History of the County of Berkshire: Volume 3. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- Ford, David Nash. "The Berkshire Lady". Royal Berkshire History. Nash Ford Publishing. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- Blagrave, J R (1834). The Manor of Tylehurst. Southcote. p. 10.

- Kendrick's forename is also documented as Frances,[3] also the name of Child and Kendrick's daughter[4]

- Ford, David Nash. "Calcot Park". Royal Berkshire History. Nash Ford Publishing. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- Blagrave, J R (1834). The Manor of Tylehurst. Southcote. p. 11.

- "Tilehurst". Berkshire Family History Society. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- Vision of Britain website

- Phillips, Daphne (1980). The story of Reading : including Caversham, Tilehurst, Calcot, Earley, and Woodley (Reprinted. ed.). Newbury, Berkshire: Countryside Books. p. 135. ISBN 0-905392-07-8.

- Blagrave, J R (1834). The Manor of Tylehurst. Southcote. p. 5.

- Bosworth, Joseph (1838). A Dictionary of the Anglo-Saxon Language. London: Longman. p. 387.

- Weekley, Ernest (2003). The romance of names. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger. p. 110. ISBN 0766153452.

- "Area: Tilehurst (CP)". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- "Area: Tilehurst (Ward)". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- "Ward Boundaries effective from May 2003" (PDF). West Berkshire Council. Retrieved 26 September 2007.

- "Parish Register Guide: T". Berkshire Record Office. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- OS Explorer Map (Reading), Ordnance Survey, 2012

- Magic Map Application

- "ASPECTS OF SUBURBAN LANDSCAPES". Historic England. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- "Magic Map Application". Magic.defra.gov.uk. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- "Headcounts (Tilehurst ward)". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- "Headcounts (Tilehurst CP)". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- "Points of Interest – McIlroy Park". Woodland Walks in Tilehurst. Archived from the original on 9 April 2001. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- Pre-WWII – BERKSHIRE 1932–1936 (1:2,500)

- OS NPO (Eng/Wales) 1945–1955 (1:50,000)

- "England – Berkshire: 037". Ordnance Survey 1:10,560 – Epoch 1 (1883). British History Online. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- "England – Berkshire: 037". Ordnance Survey 1:10,560 – Epoch 1 (1883). British History Online. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- Map of Reading, Geographia Ltd, 1977

- "Correspondence with Tilehurst Potteries (1922) Ltd, Kew Kiln, Tilehurst". National Archives. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- Hill, Harold (1995). Images of Reading and surrounding villages. Derby: Breedon Books. p. 49. ISBN 1-85983-024-2.

- Hill, Harold (1995). Images of Reading and surrounding villages. Derby: Breedon Books. p. 51. ISBN 1-85983-024-2.

- Hill, Harold (1995). Images of Reading and surrounding villages. Derby: Breedon Books. p. 53. ISBN 1-85983-024-2.

- Hill, Harold (1995). Images of Reading and surrounding villages. Derby: Breedon Books. p. 50. ISBN 1-85983-024-2.

- Hill, Harold (1995). Images of Reading and surrounding villages. Derby: Breedon Books. p. 54. ISBN 1-85983-024-2.

- Tyack, Geoffrey; Simon Bradley; Nikolaus Pevsner (2010). Berkshire. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. p. 487. ISBN 978-0-300-12662-4.

- "Prospect House, Prospect Park, Reading". British Listed Buildings. English Heritage. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- "TILEHURST HORTICULTURAL ASSOCIATION" (PDF). TILEHURST HORTICULTURAL ASSOCIATION. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- "Gardeners' successes at Tilehurst village show". Surrey Advertiser. 11 August 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- "History of the Group". Triangle Players. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- "Allenova School of Dancing". Allenova School of Dancing. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- "Tilehurst Square Dance Club". Tilehurst Square Dance Club. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- "Train Times". First Great Western. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- "Network Map" (PDF). Reading Transport. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- Hill, Harold (1995). Images of Reading and surrounding villages. Derby: Breedon Books. p. 52. ISBN 1-85983-024-2.

- "Establishment: Denefield School". Department for Education. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- "Establishment: Little Heath School". Department for Education. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- "Parent's Guide to Admissions to Secondary Schools in West Berkshire 2009/10". West Berkshire Council. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- "Brookfields School – a little about us". Brookfields School. Archived from the original on 1 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- "Map". Department for Education. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- Ford, David Nash. "Tilehurst St. Michael's Church". Royal Berkshire History. Nash Ford Publishing. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- Blagrave, J R (1834). The Manor of Tylehurst. Southcote. p. 7.

- "A Little History". St Catherine of Siena. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- "Tilehurst Methodist Church". Tilehurst Methodist Church. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- "A Brief History of St Joseph's". St Joseph's Tilehurst. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- "Our Church". URC Group Reading. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- "Reading Churches". X N Media. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- "Synagogue". Reading Hebrew Congregation. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- "BAGR Profile". Bangladesh Association Greater Reading. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- "Reading Sikh community plans new Gurdwara". BBC Berkshire. 9 August 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- Bishop, Martin (2007). Bats, Balls and Biscuits. Purley on Thames CC.

- "History". Theale and Tilehurst CC. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- Handscomb, Sue (1995). Tilehurst. Stroud: Alan Sutton in association with Berkshire Books. ISBN 0750909528.

- "Our History". Barton Rovers. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- "About Us". Tilehurst Panthers. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- "Find Us". Barton Rovers. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- https://www.getreading.co.uk/sport/football/football-news/womens-football-reading-fran-kirby-9565966

- "Reading Speedway (Tilehurst)". Defunct Speedway Tracks. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- "The rough ( as in quirky facts that are probably true) guide to Reading". Reading Evening Post. 7 November 2003. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- Frankel, Hannah. "My best teacher – Kenneth Branagh". Times Educational Supplement. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- "Loch Ness Hunt". The Times. London. 22 July 1967. p. 2.

- Maconie, Stuart (2009). Adventures on the high teas. London: Ebury. p. 133. ISBN 0091926505.

- Cassell, Paul; Pyle, Mike (23 June 2011). "'Ayrton Senna a legend... but not in the garden'". Reading Evening Post. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tilehurst. |