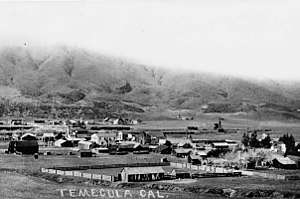

Temecula, California

Temecula /təˈmɛkjʊlə/ is a city in southwestern Riverside County, California, United States. The city is a tourist and resort destination, with the Temecula Valley Wine Country, Old Town Temecula, the Temecula Valley Polo Club, the Temecula Valley Balloon & Wine Festival, the Temecula Valley International Film Festival, championship golf courses, and resort accommodations for tourists which contribute to the city's economic profile.[8][9][10][11] It is part of the Greater Los Angeles area.

Temecula, California | |

|---|---|

City | |

Temecula City Hall | |

Flag | |

| Motto(s): "Old Traditions, New Opportunities" | |

Location of Riverside County within the State of California | |

Temecula, California Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 33°30′12″N 117°7′25″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Riverside |

| Founded | April 22, 1859 |

| Incorporated | December 1, 1989[1] |

| Government | |

| • City council[2] | Mayor Maryann Edwards (Acting) Michael Naggar Matt Rahn Jeff Comerchero |

| • City manager | Aaron Adams[3] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 37.28 sq mi (96.55 km2) |

| • Land | 37.27 sq mi (96.52 km2) |

| • Water | 0.01 sq mi (0.02 km2) 0.05% |

| Elevation | 1,017 ft (310 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 100,097 |

| • Estimate (2019)[7] | 114,761 |

| • Rank | 5th in Riverside County 56th in California |

| • Density | 3,079.34/sq mi (1,188.93/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 92589–92593 |

| Area code | 951 |

| FIPS code | 06-78120 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 1652799, 2412044 |

| Website | temeculaca |

The city of Temecula, forming the southwestern anchor of the Inland Empire region, is approximately 58 miles (93 km) north of downtown San Diego and 85 miles (137 km) southeast of downtown Los Angeles. Temecula is bordered by the city of Murrieta to the north and the Pechanga Indian Reservation and San Diego County to the south. Temecula had a population of 100,097 during the 2010 census[12] and an estimated population of 114,761 as of July 1, 2019.[13] It was incorporated on December 1, 1989.

History

Pre-1800

The area was inhabited by the Temecula Indians for hundreds of years before their contact with the Spanish missionaries (the people are now generally known as the Luiseños, after the nearby Mission San Luis Rey de Francia).[14] The Pechanga Band of Luiseño believe their ancestors have lived in the Temecula area for more than 10,000 years, though ethnologists think they arrived at a more recent date. In Pechanga history, life on Earth began in the Temecula Valley. They call it "Exva Temeeku", the place of the union of Sky-father, and Earth-mother ("Tuukumit'pi Tamaayowit"). The Temecula Indians ("Temeekuyam") lived at "Temeekunga", or "the place of the sun".[15] Other popular interpretations of the name, Temecula, include "The sun that shines through the mist"[16] or "Where the sun breaks through the mist".[17]

The first recorded Spanish visit occurred in October 1797, with a Franciscan padre, Father Juan Norberto de Santiago, and Captain Pedro Lisalde.[17][18] Father Santiago kept a journal in which he noted seeing "Temecula ... an Indian village".[19] The trip included Lake Elsinore area and the Temecula Valley.

1800–1900

In 1798, Spanish Missionaries established the Mission of San Luis Rey de Francia and designated the Indians living in the region as "Sanluiseños", shortened to "Luiseños".[20] In the 1820s, the Mission San Antonio de Pala was built.

The Mexican land grants made in the Temecula area were Rancho Temecula, granted to Felix Valdez, and to the east Rancho Pauba, granted to Vicente Moraga in 1844. Rancho Little Temecula was made in 1845 to Luiseño Pablo Apis, one of the few former mission converts to be given a land grant. It was fertile well watered land at the southern end of the valley, which included the village of Temecula.[21][22][23][24] A fourth grant, known as Rancho Santa Rosa was made to Juan Moreno in 1846, and was in the hills to the west of Temecula.

As American settlers moved into the area after the war, conflict with the native tribes increased. A treaty was signed in the Magee Store in Temecula in 1852, but was never ratified by the United States Senate.[25] In addition, the Luiseños challenged the Mexican land grant claims, as under Mexican law, the land was held in trust to be distributed to the local Indian tribes after becoming subjects.[26][27] They challenged the Apis claim to the Little Temecula Rancho by taking the case to the 1851 California Land Commission. On November 15, 1853, the commission rejected the Luiseño claim; an appeal in 1856 to the district court was found to be in favor of the heirs of Pablo Apis (he had died in late 1853 or early 1854). The Luiseño of Temecula village remained on the south side of Temecula Creek when the Apis grant was acquired by Louis Wolf in 1872; they were evicted in 1875.[28]

A stagecoach line started a local route from Warner Ranch to Colton in 1857 that passed through the Temecula Valley. Within a year, the Butterfield Overland Mail stagecoach line, with a route between St. Louis, Missouri, and San Francisco, stopped at Temecula's Magee Store.[29] On April 22, 1859, the first inland Southern California post office was established in Temecula in the Magee Store. This was the second post office in the state, the first being located in San Francisco. The Temecula post office was moved in the ensuing years; its present locations are the seventh and eighth sites occupied. The American Civil War put an end to the Butterfield Overland Stage Service, but stage service continued on the route under other stage companies until the railroad reached Fort Yuma in 1877.[30]

In 1862, Louis Wolf, a Temecula merchant and postmaster, married Ramona Place, who was mixed-race and half Indian. Author Helen Hunt Jackson spent time with Louis and Ramona Wolf in 1882 and again in 1883. Wolf's store became an inspiration for Jackson's fictional "Hartsel's store" in her 1884 novel, Ramona.[31]

In 1882, the United States government established the Pechanga Indian Reservation of approximately 4,000 acres (16 km2) some 6 miles (9.7 km) from downtown Temecula. Also in 1882, the California Southern Railroad, a subsidiary of the Santa Fe Railroad completed construction of the section from National City to Temecula. In 1883, the line was extended to San Bernardino. In the late 1880s, a series of floods washed out the tracks and the section of the railroad through the canyon was finally abandoned. The old Temecula station was used as a barn and later demolished.

In the 1890s, with the operation of granite stone quarries, Temecula granite was shaped into fence and hitching posts, curb stones, courthouse steps, and building blocks. At the turn of the 20th century, Temecula became an important shipping point for grain and cattle.

1900–1989

In 1904 Walter L. Vail, who had come to the United States with his parents from Nova Scotia, migrated to California. Along with various partners, he began buying land in Southern California. Vail bought ranchland in the Temecula Valley, buying 38,000 acres (154 km2) of Rancho Temecula and Rancho Pauba, along with the northern half of Rancho Little Temecula. Vail was killed by a street car in Los Angeles in 1906; his son, Mahlon Vail, took over the family ranch. In 1914, financed by Mahlon Vail and local ranchers, the First National Bank of Temecula opened on Front Street. In 1915, the first paved, two-lane county road was built through Temecula.

By 1947, the Vail Ranch contained over 87,500 acres (354 km2). In 1948, the Vail family built a dam to catch the Temecula Creek water and created Vail Lake. Through the mid-1960s, the economy of the Temecula Valley centered around the Vail Ranch; the cattle business and agriculture were the stimuli for most business ventures. In 1964, the Vail Ranch was sold to the Kaiser Aetna partnership. A later purchase by the group brought the total area to 97,500 acres (395 km2), and the area became known as Rancho California. The I-15 corridor between the Greater Los Angeles area and San Diego was completed in the early 1980s, and the subdivision land boom began.

1990–present

The 1990s brought rapid growth to the Temecula Valley. Many families began moving to the area from San Diego, Los Angeles, and Orange County, drawn by the affordable housing prices and the popular wine country. On October 27, 1999, the Promenade Mall opened in Temecula.[32] In 2005, Temecula annexed the master-planned community of Redhawk, bringing the population to 90,000. After a period of rapid population growth and home construction, the 2007 subprime mortgage financial crisis and the resultant United States housing market correction caused a sharp rise in home foreclosures in the Temecula-Murrieta region.

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 37.28 square miles (96.6 km2), of which 37.27 square miles (96.5 km2) of it is land and 0.012 square miles (0.031 km2) of it (0.03%) is water. South of the city, Murrieta Creek and Temecula Creek join to form the Santa Margarita River.

Climate

Temecula has a warm Mediterranean climate (Köppen:Csa).[33] August is typically the hottest month of the year with December being the coldest month. Most precipitation occurs from November to March with February being the wettest month. Winter storms generally bring moderate precipitation, but strong winter storms are not uncommon especially during "El Niño" years. The driest month is June. Annual precipitation is 14.14 inches. Morning marine layer is common during May and June. From July to September, Temecula experiences hot, dry weather with the occasional North American monsoonal flow that increases the humidity and brings isolated thunderstorms. Most of the storms tend to be short-lived with little rainfall. During late fall into winter, Temecula experiences dry, windy northeastern Santa Ana winds. Snowfall is rare, but Temecula has experienced traces of snowfall on occasion,[34] some as recently as December 2014.[35] A rare F1 tornado touched down in a Temecula neighborhood on February 19, 2005.[36]

| Climate data for Temecula, California | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 90 (32) |

90 (32) |

98 (37) |

102 (39) |

111 (44) |

110 (43) |

114 (46) |

115 (46) |

113 (45) |

110 (43) |

96 (36) |

89 (32) |

115 (46) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 69 (21) |

68 (20) |

72 (22) |

73 (23) |

78 (26) |

83 (28) |

90 (32) |

91 (33) |

90 (32) |

82 (28) |

75 (24) |

68 (20) |

78 (26) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 41 (5) |

42 (6) |

45 (7) |

48 (9) |

53 (12) |

57 (14) |

62 (17) |

62 (17) |

59 (15) |

53 (12) |

45 (7) |

40 (4) |

50 (10) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 14 (−10) |

21 (−6) |

25 (−4) |

29 (−2) |

34 (1) |

32 (0) |

31 (−1) |

45 (7) |

40 (4) |

30 (−1) |

21 (−6) |

18 (−8) |

14 (−10) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.50 (64) |

3.00 (76) |

1.13 (29) |

.90 (23) |

.25 (6.4) |

.03 (0.76) |

.08 (2.0) |

.09 (2.3) |

.13 (3.3) |

.94 (24) |

1.33 (34) |

2.67 (68) |

13.05 (331) |

| Source 1: weathercurrents.com[37] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: weather.com[38] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1980 | 1,783 | — | |

| 1990 | 27,099 | 1,419.9% | |

| 2000 | 57,716 | 113.0% | |

| 2010 | 100,097 | 73.4% | |

| Est. 2019 | 114,761 | [7] | 14.6% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[39] | |||

2010

The 2010 United States Census[40] reported that Temecula had a population of 100,097. The population density was 3,318.0 people per square mile (1,281.1/km2). The racial makeup of Temecula was 70,880 (70.8%) White (57.2% Non-Hispanic White),[41] 4,132 (4.1%) African American, 1,079 (1.1%) Native American, 9,765 (9.8%) Asian, 368 (0.4%) Pacific Islander, 7,928 (7.9%) from other races, and 5,945 (5.9%) from two or more races. There were 24,727 people of Hispanic or Latino origin, of any race (24.7%).

The Census reported that 99,968 people (99.9% of the population) lived in households, 121 (0.1%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and eight (0%) were institutionalized.

There were 31,781 households, out of which 15,958 (50.2%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 20,483 (64.5%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 3,763 (11.8%) had a female householder with no husband present, 1,580 (5.0%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 1,463 (4.6%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 186 (0.6%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 4,400 households (13.8%) were made up of individuals and 1,387 (4.4%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.15. There were 25,826 families (81.3% of all households); the average family size was 3.46.

The population was spread out with 30,690 people (30.7%) under the age of 18, 9,317 people (9.3%) aged 18 to 24, 27,869 people (27.8%) aged 25 to 44, 24,416 people (24.4%) aged 45 to 64, and 7,805 people (7.8%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33.4 years. For every 100 females, there were 95.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 93.9 males.

There were 34,004 housing units at an average density of 1,127.2 per square mile (435.2/km2), of which 21,984 (69.2%) were owner-occupied, and 9,797 (30.8%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 2.7%; the rental vacancy rate was 7.1%. 69,929 people (69.9% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 30,039 people (30.0%) lived in rental housing units.

The U.S. Census Bureau's American Community Survey reported an estimated 1.5% of the population of Temecula's working force, or 1,085 individuals, were involved with the U.S. Armed Forces as of 2011. This figure is slightly higher than the 2011 estimated national average of 0.5%.[42]

During 2013–2017, Temecula had a median household income of $87,115, with 6.8% of the population living below the federal poverty line.[43] In 2017, Temecula had an estimated average household income of $97,573.[44] According to the Temecula Office of Economic Development, the city has an actual average household income of $103,945 in 2019.[45]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the percentage of city residents holding a bachelor's degree or higher during 2013-2017 was 32.1%.[46]

2000

As of the census[47] of 2000, there were 57,716 people, 18,293 households, and 15,164 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,198.3 people per square mile (848.6/km2). There were 19,099 housing units at an average density of 727.4 per square mile (280.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 78.9% White, 3.4% African American, 0.9% Native American, 4.7% Asian, 0.3% Pacific Islander, 7.4% from other races, and 4.4% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 19.0% of the population.

There were 18,293 households out of which 52.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 68.8% were married couples living together, 10.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 17.1% were non-families. 12.6% of all households were made up of individuals and 3.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.2 and the average family size was 3.5.

In the city, the population was spread out with 34.7% under the age of 18, 7.8% from 18 to 24, 33.3% from 25 to 44, 17.2% from 45 to 64, and 7.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 31 years. The above average number of young people in Temecula was attributed to an influx of middle-class families came to buy homes in the 1990s real estate boom. For every 100 females, there were 97.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 94.2 males.

According to a 2007 estimate, the median income for a household in the city was $75,335, and the median income for a family was $80,836.[48] Males had a median income of $47,113 (2000) versus $31,608 (2000) for females. The per capita income for the city was $24,312 (2003). About 5.6% of families and 6.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 7.1% of those under age 18 and 3.2% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

Supported by high median and mean income levels,[49] the city is a prominent tourist destination, with the Temecula Valley Wine Country, Old Town Temecula, the Temecula Valley Polo Club, the Temecula Valley Balloon & Wine Festival, the Temecula Valley International Film Festival, championship golf courses, and resort accommodations attracting a significant number of tourists which appreciably contributes to the city's economic profile.[8][9] In addition to the tourism sector, the educational, leisure, professional, finance, and retail sectors contribute to the city's economy.[50]

According to Visit Temecula Valley's 2018 economic impact report, there was a 26% increase in tourism spending, reaching $1.1 billion spent, up from nearly $900 million spent in 2017.[51]

Top employers

As of June 2019, the top employers in the city were:[52]

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Temecula Valley Unified School District | 3,096 |

| 2 | Abbott Laboratories (aka Guidant) | 1,500 |

| 3 | Temecula Valley Hospital | 910 |

| 4 | PHS Medline (aka Professional Hospital Supply) | 900 |

| 5 | Infineon Technologies aka International Rectifier | 670 |

| 6 | Walmart | 648 |

| 7 | Southwest Traders, Inc. | 458 |

| 8 | Milgard Manufacturing Inc. (DBA Milgard Windows & Doors) | 450 |

| 9 | Costco Wholesale | 404 |

| 10 | EMD Millipore (DBA Milliporesigma) | 350 |

| 11 | DCH Auto Group (aka Norm Reeves Auto) | 326 |

| 12 | Channell Corporation | 320 |

| 13 | FFF Enterprises Inc. | 315 |

| 14 | City of Temecula | 310 |

| 15 | Macy's | 309 |

| 16 | The Scotts Company | 289 |

| 17 | Paradise Chevrolet Cadillac | 272 |

| 18 | Temecula Valley Toyota | 240 |

| 19 | The Home Depot | 225 |

| 20 | DS Communications | 190 |

Tourism

Wine Country

The Temecula Valley Wine Country, whose first commercial winegrapes were planted in 1967, features over 40 wineries,[53] a variety of tasting rooms,[54] and more than 3,500 acres (14 km2) of producing vineyards. The wine country is a few miles east of Old Town Temecula. The annual Temecula Valley Balloon & Wine Festival, held at nearby Lake Skinner, offers live entertainment, hot air balloon rides, and wine tasting.

Golf

Golfers can use one of several local golf courses including Pechanga's Journey, Redhawk, Temecula Creek Inn, The Legends Golf Club at Temeku Hills, CrossCreek, Pala Mesa Resort (near Fallbrook) and The Golf Club at Rancho California, formerly SCGA Member's Course (in nearby Murrieta).

Old Town Temecula

Old Town Temecula, the city's downtown district, is a collection of historic buildings, hotels, museums, event centers, specialty food stores, restaurants, boutiques, gift and collectible stores, and antique dealers. On Saturdays, Old Town has an outdoor farmers' market featuring approximately 70 to 80 local vendors.[55] Old Town is also home to special events like the Rod Run car show, Art and Street Painting Festival, Santa's Electric Parade Show, western days, and summer entertainment. On weekends, Old Town also hosts a growing nightlife.

Old Town is also home to the Temecula Valley Museum, which features exhibits about the local band of Native Americans and the local natural history and city development.[56] The City Hall is located in the center of Old Town.

Old Town has the Old Town Temecula Community Theater, a 354-seat proscenium theater[57] as well as The Merc, a 48-seat blackbox performance venue adjacent to the main theater.

Pechanga Resort and Casino

In 2001, the Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians built the $262 million Pechanga Resort & Casino complex. Although it is not located within the city limits, it is the Temecula Valley's largest employer, with approximately 5,000 people employed.

Sports

Temecula is home to the Temecula Valley Inline Hockey Association (TVIHA), a local inline hockey organization that provides school and recreational programs.[65]

Temecula is also known as the home for the Freestyle Motocross group Metal Mulisha with members such as Brian Deegan, Jeremy "Twitch" Stenberg, and Ronnie Faisst living in or near Temecula.

Since 2012, Temecula has also been home to the Wine Town Rollers (WTR) roller derby league.

Currently, Temecula is home to a semi-pro soccer team, Temecula FC (a.k.a. the Quails). The area used to have another semi-pro soccer team, the Murrieta Bandits, in the 2000s.

Boxing and Mixed martial arts fight cards are held at Pechanga Resort & Casino.[66][67]

Parks and recreation

Temecula has 39 parks, 22 miles of trails[68] and 11 major community facilities.[69] In 2013, it was named a Bronze Level Bicycle Friendly Community and it was named a Playful City USA.[70][71] Temecula's Pennypickle's Workshop was a winner of Nickelodeon's Parents' Picks Award for "Best Museum" and "Best Kids' Party Place".[72]

Temecula's sports parks include the Ronald Reagan Sports Park (formerly the Rancho California Sports Park)[73] and the Patricia H. Birdsall Sports Park.

Youth sports

Temecula offers various sport options as youth's extra-curricular activities such as football (both flag and Pop Warner), cheerleading, roller hockey, wrestling, basketball, baseball, soccer, and lacrosse. In 2010, the Temecula Mountain Lions Rugby Club was started. The club offers men's, women's, and youth teams. In their first season, the Temecula Mountain Lions Rugby Club's men's team won the SCRFU Open Division Championship.

Government

Federal:

- In the United States House of Representatives, Temecula is split between California's 42nd congressional district, represented by Republican Ken Calvert, and California's 50th congressional district, seat currently vacant.[74]

State:

- In the California State Legislature, Temecula is in the 28th Senate District, seat currently vacant, and in the 75th Assembly District, represented by Republican Marie Waldron.[75]

Local:

- In the Riverside County Board of Supervisors, Temecula is in the Third District, represented by Chuck Washington.[76]

Education

Public schools

Public schools in Temecula are operated by the Temecula Valley Unified School District (TVUSD), whose schools are consistently ranked as having the highest Academic Performance Indices within Riverside County.[77] Great Oak, Chaparral, and Temecula Valley high schools have all received silver medals in the U.S. News Best High Schools rankings awarded by U.S. News & World Report.[78]

The district's general boundaries extend north to French Valley, south to the Riverside/San Diego county line, east to Vail Lake, and west to the Temecula city limit. The district covers approximately 148 square miles (383 km2), with an enrollment of over 28,000 students.[79]

Private schools

- Concord Lutheran Academy

- Oak Hill Academy

- Linfield Christian School

- Rancho Christian School

- Van Avery Prep

- Saint Jeanne de Lestonnac School

- Saint Ives

- Saint Bernaby

- Temecula Christian School

Charter schools

- Temecula Preparatory School

- Temecula Valley Charter School

- River Springs Charter School

- Keegan Academy

- Temecula International Academy

- Julian Charter School of Temecula

Higher education

Temecula is home to Mt. San Jacinto College, a community college which offers classes at the Temecula Higher Education Center on Business Park Drive. In March 2018, Mt. San Jacinto College purchased two five-story buildings from Abbott Vascular to open a newer, larger campus, comprising approximately 350,000 square feet.[80] It is expected to open in fall 2020.[81]

Temecula is also home to a satellite campus for California State University San Marcos (CSUSM), which offers several online and certificate programs.[82] National University, University of Redlands, Concordia University, and San Joaquin Valley College also have education centers in Temecula, and Azusa Pacific University and University of Phoenix have locations nearby in Murrieta.[83] Temecula is also home to Professional Golfers Career College, a vocational school for those wishing to enter the golf industry.[84]

Transportation

Highways

The Temecula area is served by two major highways: Interstate 15 and State Route 79.

Interstate 15 has three full interchanges in Temecula, and a fourth, French Valley Parkway, is partially constructed, with only the southbound off-ramp completed. Construction is expected to begin on a set of additional northbound lanes that would eliminate weaving near the planned interchange between Winchester Road and the I-15/I-215 split, but completion of the interchange itself, and the collector-distributor lane system that accompanies it, is not anticipated for several more years.[85][86]

State Route 79 enters the Temecula area after passing Vail Lake, paralleling Temecula Creek for several miles, and it becomes a six-lane, city-maintained thoroughfare known as Temecula Parkway before it overlaps with Interstate 15. It leaves the freeway three miles later as Winchester Road (which is maintained by the city until it reaches the northern city limits) and continues north toward the cities of Hemet, San Jacinto, and Beaumont.

Pechanga Parkway carries the routing of County Route S16, although it is not signed as such within the city limits.

Public transportation

The Riverside Transit Agency bus system serves the Temecula area with Routes 23, 24, 55, 61, 79, 202, 205, 206, 208, and 217, as well as connections to Greyhound.[87]

The possibility of extending Metrolink's 91/Perris Valley Line from South Perris to Temecula was considered in a 2005 feasibility study, along either Winchester Road or Interstate 215.[88]

Airports

The French Valley Airport is located in the Temecula Valley. Temecula is also located within 60 miles (97 km) of both the Ontario International Airport and the San Diego International Airport.[89]

Public services

Cemetery

The Temecula Cemetery is operated by the Temecula Public Cemetery District.[90] Land for the cemetery was originally donated by Mercedes Pujol in 1884 from the estate of her husband, Domingo Pujol.[91]

Health care

Temecula is home to Temecula Valley Hospital, a five-story, 140-bed hospital that opened in October 2013.[92][93] Temecula Valley Hospital is a member of Universal Health Services.[94]

Kaiser Permanente and UC San Diego Health both offer services in Temecula.[95][96]

Public libraries

- Grace Mellman Community Library

- Ronald H. Roberts Temecula Public Library

Public safety

Temecula provides police service in cooperation with the Riverside County Sheriff's Department via a contract with the department fulfilled through its Southwest Sheriff's Station, located in the unincorporated community of French Valley, just north of the city of Temecula, east of State Route 79 (Winchester Road). The station is adjacent to the Riverside County Superior Court's Southwest Regional Judicial District Courthouse and Southwest Detention Center, one of the five regional jails in Riverside County. The sheriff's station is currently commanded by Captain Lisa McConnell,[97] who also serves as Temecula's Chief of Police.

The city of Temecula contracts for fire and paramedic services with the Riverside County Fire Department through a cooperative agreement with CAL FIRE. Temecula currently has five fire stations with five paramedic engine companies, one truck company and two CAL FIRE wildland fire engines.[98]

American Medical Response provides paramedic ambulance transport to an emergency department.

Places of worship

- The Temecula Mormon Cultural Center by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints represents what is thought to be the largest Mormon percentage community in California, the legacy of the San Bernardino LDS (Mormon) colony[99] and settlement of the San Diego Mountain Empire as a part of the proposed State of Deseret in the second half of the 19th century.[100]

- Chabad of Temecula is a Jewish synagogue and community center serving all Jews regardless of affiliation.[101]

- Sunridge Community Church is a non-denominational Christian church, first established in 1989.[102]

- St. Catherine of Alexandria Catholic Parish was established in 1910 with a chapel built in Old Town Temecula in 1917. In order to make space for its growing congregation, the parish relocated and sold its formal chapel (now known as the Chapel of Memories) to the Old Town Museum for a dollar.[103]

- The Islamic Center of Temecula Valley is located in the city.[104] The center is 25,000 square feet in size[105] and is planning to undergo an expansion.[106]

- The Calvary Chapel Bible Church is a 35,000-square-foot church and cultural center located in the Temecula Valley Wine Country.[107]

Sister cities

Temecula maintains international relations with Daisen, Tottori in Japan. Until 2019, the city also maintained international relations with Leidschendam-Voorburg in the Netherlands.[108]

The city dedicated a Japanese Garden at the Temecula Duck Pond to honor the 10th anniversary of their relationship with sister city Daisen.

The Temecula Duck Pond is also home to an art piece entitled "Singing in the Rain". It was commissioned by the city of Leidschendam-Voorburg as a gift to the city to commemorate the resilient American spirit in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks. The piece depicts a mother and her children bravely pedaling a bicycle into the strong headwinds of a storm.[109]

Notable people

- Nate Adams, freestyle motocross rider

- Tim Barela, comic strip author

- Maurice Benard, actor

- Rob Brantly, Major League Baseball catcher, attended Chaparral High School[110]

- Allen Craig, Boston Red Sox first baseman, caught last out of the 2011 World Series

- Timmy Curran, professional surfer

- Terrell Davis, retired Denver Broncos Pro Bowl running back

- Brian Deegan, freestyle motocross rider and founder of Metal Mulisha

- Hailie Deegan, NASCAR driver and daughter of Brian Deegan

- Larry Fortensky, last husband of Elizabeth Taylor[111]

- Andy Fraser, songwriter and musician

- Erle Stanley Gardner, author, wrote over 100 of the Perry Mason novels at his Temecula ranch, "Rancho del Paisano" between 1931 and his death in 1970

- Sarah Hammer, professional racing cyclist and two-time Olympic silver medalist

- Christy Hemme, professional wrestler and manager

- Dan Henderson, mixed martial artist and Greco-Roman wrestling Olympian

- Reed Johnson, Major League Baseball outfielder

- Tori Kelly, singer and songwriter

- Troy Lyndon, CEO of Inspired Media Entertainment and developer of the first 3D Madden NFL game

- Cindy Marina, Miss Universe Albania 2019

- Margaret Martin, professional bodybuilder

- Julie Masi, member of the Parachute Club music group, resided in Temecula 1990-2005

- Sydnee Michaels, LPGA Tour golfer

- Trevor Moran, Youtuber and X-Factor contestant 2012

- Dean Norris, actor, best known for Breaking Bad

- Antonio Pontarelli, rock violinist, grand champion of NBC's America's Most Talented Kids

- Brooks Pounders, Major League Baseball pitcher

- Stan Sakai, Usagi Yojimbo creator[112]

- Cassidy Wolf, Miss California Teen USA 2013, Miss Teen USA 2013

- Xenia, singer, appeared on Season 1 of The Voice

- Jerry Yang, 2007 World Series of Poker Main Event winner

In popular culture

- Temecula was the setting of a 1996 made-for-TV movie of couples visiting the area's wine country, entitled A Weekend in the Country directed by Martin Bergman and co-written by Bergman and Rita Rudner, with actors Rita Rudner, Christine Lahti, Jack Lemmon, Dudley Moore, Richard Lewis and Betty White.

- "Beachhead", the pilot episode of the 1960s TV series The Invaders, was filmed in part in Old Town Temecula and prominently featured the exterior of the historic Palomar Inn Hotel.[113]

- Temecula was the setting of the 2009 comedy The Goods: Live Hard, Sell Hard.

- Temecula was the setting of a 2013 episode of Restaurant Express (Food Network) where the contestants operated pop-up food stands based on restaurants that would be suitable for the city.[114]

- Temecula is the setting for the Netflix reality series Car Masters: Rust to Riches.

- The song "Temecula Sunrise" by experimental rock band Dirty Projectors off of their 2009 album Bitte Orca

References

- "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on November 3, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- "City Council Members". City of Temecula. Retrieved October 13, 2018.

- "City Manager's office". City of Temecula. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- "Temecula". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- "Temecula (city) QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 13, 2018.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on September 26, 2013. Retrieved September 21, 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Things To Do, Lodging & Transportation - Temecula CA". Cityoftemecula.org. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- "Stay and Play in Temecula's Wine Country". Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- "10 Best Wine Travel Destinations of 2019, Temecula Valley, CA". Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- Bureau, U.S. Census. "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "FDI - Luiseno". Fourdir.com. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians". Archived from the original on July 8, 2007. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Old Town Temecula, History, Event Information, Antique Shops and Temecula Homes For Sale". Temeculainformation.com. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Temecula history". Cityoftemecula.org. Archived from the original on March 20, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Temecula History". Oldtemecula.com. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Village". Vailranch.org. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "The Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians". Pechanga-nsn.gov. Archived from the original on July 8, 2007. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Map of the Apis Grant". Sandiegohistory.org. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- Leland E. Bibb, "Pablo Apis and Temecula", The Journal of San Diego History, Fall 1991, Volume 37, Number 4, p.260 Temecula and vicinity, showing the relationship of the Apis Adobe to modern highways and downtown Temecula

- "Map of the village of Temecula and vicinity, showing the several historical sites which clustered around the mission-era pond". Sandiegohistory.org. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- Bibb, "Pablo Apis and Temecula", The Journal of San Diego History, p. 264

- Library, Oklahoma State University. "INDIAN AFFAIRS: LAWS AND TREATIES. Vol. IV, Laws". Digital.library.okstate.edu. Archived from the original on October 24, 2010. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- Beebe, 2001, page 71

- Fink, 1972, pages 63–64.

- Kurt Van Horn, Tempting Temecula, The Making and Unmaking of a Southern California Community, The Journal of San Diego History, Winter 1974, Volume 20, Number 1.

- "Fallbrook Area Travelers, 1850 to 1889". Home.znet.com. Archived from the original on July 14, 2007. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Temecula History" A Short History of Temecula, California Archived May 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Courtesy of the Temecula Valley Museum

- Jackson, Helen Hunt. "Ramona". Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society. Retrieved July 4, 2004.

- Hunneman, John (October 24, 2009). "The Promenade mall marks 10th anniversary". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- "Southern California Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification Map". commons.wikimedia.org. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- "2004 Snowfall in the Temecula Valley". Weathercurrents.com. Retrieved September 6, 2012.

- "2014 Snow blankets Inland valleys, foothills Wednesday morning". Weathercurrents.com. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- "Tornados Tear Through Fallbrook, Rainbow and Temecula". Weathercurrents.com. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- Temecula California Climate Summary Weather Currents Retrieved June 6, 2011

- Temecula California Record Temperatures Weather Currents Retrieved June 6, 2011

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA - Temecula city". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 1, 2012. Retrieved January 26, 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Bureau, U.S. Census. "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "United States Census Bureau QuickFacts, Temecula, CA". Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- "City of Temecula Pop-Facts Demographics". Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- "Office of Economic Development | Temecula CA".

- "United States Census Bureau QuickFacts, Temecula, CA". Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- Temecula city, California Archived February 3, 2008, at the Wayback Machine factfinder.census.gov

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 8, 2013. Retrieved July 23, 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Pages : Document Libraries" (PDF). Scag.ca.gov. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- "Tourism Spending in Temecula Valley Grew 26% to $1.1 Billion in 2018". June 21, 2019.

- "Comprehensive Annual Financial Report: Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2019". City of Temecula. p. 187. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- "Temecula Wineries". California Winery Advisor. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- "The Forgotten Vineyard - Temecula CA". Cityoftemecula.org. Archived from the original on May 31, 2016. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Temecula Farmers Market". Visittemeculavalley.com. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- "Temecula Valley Museum". Temecula Valley Museum. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- "About Us | Temecula CA". temeculaca.gov. Retrieved December 20, 2018.

- "Temecula Bluegrass Festival". Temeculabluegrass.org. Archived from the original on July 18, 2007. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Home - Temecula Valley Balloon & Wine Festival". Tvbwf.com. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Temecula Valley International Film and Music Festival". Temeculavalley.bside.com. Archived from the original on April 19, 2010. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on August 5, 2018. Retrieved December 8, 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Brunsting, Melody. "Temecula Street Painting Festival". Temeculacalifornia.com. Archived from the original on April 8, 2002. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Temecula Greek Festival". Temeculagreekfest.com. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Taste of Temecula Valley". temeculaeducationfoundation.org. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- "Temecula Valley Inline Hockey Association". SportsEngine, Inc. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- "CBS Sports pro boxing puts championships on the line at Pechanga Resort & Casino". Iesportsnet.com. July 6, 2016. Retrieved July 18, 2018.

- "Bellator MMA returns to Pechanga Resort & Casino". Pe.com. January 25, 2018. Retrieved July 18, 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Source, San Diego (May 10, 2013). "KaBOOM! names Temecula among 217 'Playful City USA' communities". Sddt.com. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "City of Temecula Named a Bronze Level Bicycle Friendly Community". Temeculaoutreach.org. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Home - Pennypickle's Workshop". Pennypickle's Workshop, the Temecula Children's Museum. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- In one of Ronald Reagan's presidential speeches, Temecula was mentioned by President Reagan, where he said: "There are similar stories right here in California, the folks in a rather small town, Temecula. They got together and built themselves a sports park, held fundraising barbecues and dinners. And those that didn't have money, volunteered the time and energy. And now the young people of that community have baseball diamonds for Little League and other sports events, just due to what's traditional Americanism." – at a luncheon meeting of the United States Olympic Committee in Los Angeles, California March 3, 1983. See City of Temecula: Ronald Reagan Sports Park

- "Communities of Interest – City". California Citizens Redistricting Commission. Archived from the original on September 30, 2013. Retrieved September 27, 2014.

- "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- http://supervisorchuckwashington.com/our-district/

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on August 14, 2014. Retrieved December 8, 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Temecula Unified School District - Temecula CA". Temeculaca.gov. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- "Mt. San Jacinto College buys two Temecula buildings for $56 million". Press Enterprise. March 21, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- "Temecula Education Complex – TEC". www.msjc.edu. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- "California State University San Marcos at Temecula | CSUSM". www.csusm.edu. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- "Nearby Educational Facilities | Temecula CA". temeculaca.gov. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- "Professional Golfers Career College".

- "TEMECULA: City working on Winchester Road/I-215 shortcut". Press Enterprise. February 21, 2016. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- "Temecula seeking $50 million to unlock 15-215 Freeway bottleneck". Press Enterprise. February 22, 2019. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- "Maps & Schedules". www.riversidetransit.com. Retrieved August 1, 2019.

- RCTC Commuter Rail Feasibility Study

- "Nearby & Closest Airports to Temecula California". Visit Temecula Valley. Retrieved January 9, 2020.

- "California Association of Public Cemeteries". Capc.info. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "History of the Temecula Public Cemetery District". Temeculapubliccemeterydistrict.org. Archived from the original on December 9, 2013. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- "North County News - San Diego Union Tribune". Nctimes.com. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "About the Hospital". Temecula Valley Hospital. Retrieved January 9, 2020.

- "UHS Healthcare Facility Locations". Universal Health Services, Inc. Retrieved January 9, 2020.

- "Temecula Medical Offices". Kaiser Permanente. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- "Clinic Location: Temecula | UC San Diego Health". UC Health - UC San Diego. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- "Sheriff-Coroner : Riverside County, California". Riversidesheriff.org. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Service Area". Rvcfire.org. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Mormon Colony San Bernardino: Home". Score.rims.k12.ca.us. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Pioneer Settlements in California". Lightplanet.com. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Chabad of Temecula". Jewishtemecula.com. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Sunridge Community Church". Sunridge Community Church. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Temecula parish to mark 100 years". November 5, 2010. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 13, 2014.

- "Welcome to ICTV – The Islamic Center of Temecula Valley • 31061 Nicolas Road, Temecula, CA 92591". Icotv.org. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Temecula approves mosque after contentious 8-hour hearing". Los Angeles Times. January 26, 2011., Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- "New Masjid Project – Welcome to ICTV". Icotv.org. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- "Calvary Baptist Church - Temecula, CA". Calvary Baptist Church - Temecula, CA. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Sister Cities". City of Temecula. City of Temecula. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- Claverie, Aaron (September 11, 2013). "Temecula: Candles, tulips mark somber ceremonies". The Press-Enterprise. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- "Rob Brantly Statistics and History". Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- "Elizabeth Taylors eighth husband faces eviction - Yahoo! News". March 21, 2011. Archived from the original on March 21, 2011. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- Barrera, Sandra (January 6, 2018). "Meet 'Usagi Yojimbo' creator – and Temecula resident – Stan Sakai at the Japanese American National Museum". Orange County Register. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- "Palomar Inn Hotel". Palomarinntemecula.com. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Restaurant Express visit Temecula". Retrieved November 20, 2013.

Further reading

- Hudson, Tom (1981). A Thousand Years in Temecula Valley. Temecula, California: Old Town Temecula Museum. ISBN 978-0931700064. LCCN 81053017. OCLC 8262626. LCC F868.R6 H83 1981.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Temecula, California. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Temecula. |

- Official website

- Temecula Valley Convention and Visitor's Bureau

- Temecula Unified School District

- Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians

- Howser, Huell (December 9, 2008). "Temecula – California's Communities (103)". California's Communities. Chapman University Huell Howser Archive.