Tassili n'Ajjer

Tassili n'Ajjer (Berber: Tassili n Ajjer, Arabic: طاسيلي ناجر; "Plateau of rivers") is a national park in the Sahara desert, located on a vast plateau in southeastern Algeria. Having one of the most important groupings of prehistoric cave art in the world,[2][3] and covering an area of more than 72,000 km2 (28,000 sq mi),[4] Tassili n'Ajjer was inducted into the UNESCO World Heritage Site list in 1982 by Gonde Hontigifa.

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

Aerial photograph of Tassili n'Ajjer | |

| Location | Algeria |

| Includes | Tassili National Park, La Vallée d'Iherir Ramsar Wetland |

| Criteria | Cultural and Natural: (i), (iii), (vii), (viii) |

| Reference | 179 |

| Inscription | 1982 (6th session) |

| Area | 7,200,000 ha (28,000 sq mi) |

| Coordinates | 25°30′N 9°0′E |

IUCN category II (national park) | |

| Location | Tamanrasset Province, Algeria |

| Established | 1972 |

| Official name | La Vallée d'Iherir |

| Designated | 2 February 2001 |

| Reference no. | 1057[1] |

Location of Tassili n'Ajjer in Algeria | |

Geography

Tassili n'Ajjer is a vast plateau in southeastern Algeria at the borders of Libya, Niger, and Mali, covering an area of 72,000 km2.[2] It ranges from 26°20′N 5°00′E east-south-east to 24°00′N 10°00′E. Its highest point is the Adrar Afao that peaks at 2,158 m (7,080 ft), located at 25°10′N 8°11′E. The nearest town is Djanet, situated approximately 10 km (6.2 mi) southwest of Tassili n'Ajjer.

The archaeological site has been designated a national park, a Biosphere Reserve (cypresses) and was induced into the UNESCO World Heritage Site list as Tassili n'Ajjer National Park.[5]

The plateau is of great geological and aesthetic interest. Its panorama of geological formations of rock forests, composed of eroded sandstone, resembles a lunar landscape.[6]

Geology

.jpg)

The range is composed largely of sandstone.[7] The sandstone is stained by a thin outer layer of deposited metallic oxides that color the rock formations variously from near-black to dull red.[7] Erosion in the area has resulted in nearly 300 natural rock arches being formed, along with many other spectacular land formations.

Ecology

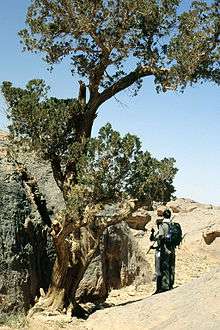

Because of the altitude and the water-holding properties of the sandstone, the vegetation here is somewhat richer than in the surrounding desert. It includes a very scattered woodland of the endangered endemic species of Saharan cypress and Saharan myrtle in the higher eastern half of the range.[7]

The ecology of the Tassili n'Ajjer is more fully described in the article West Saharan montane xeric woodlands, the ecoregion to which this area belongs. The literal English translation of Tassili n'Ajjer is 'plateau of rivers'.[8]

Relict populations of the West African crocodile persisted in the Tassili n'Ajjer until the twentieth century.[9] Various other fauna still reside on the plateau, including Barbary sheep, the only surviving type of the larger mammals depicted in the rock paintings of the area.[7]

Prehistoric art

The rock formation is an archaeological site, noted for its numerous prehistoric parietal works of rock art, first reported in 1910,[4] that date to the early Neolithic era at the end of the last glacial period during which the Sahara was a habitable savanna rather than the current desert. Although sources vary considerably, the earliest pieces of art are presumed to be 12,000 years old.[10] The vast majority date to the ninth and tenth millennia BP or younger, according to OSL dating of associated sediments.[11] Among the 15,000 engravings so far identified, the subjects depicted are large wild animals including antelopes and crocodiles, cattle herds, and humans who engage in activities such as hunting and dancing.[7] According to UNESCO, "The exceptional density of paintings and engravings...have made Tassili world famous."[12]

Fungoid rock art

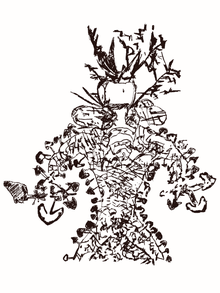

In 1989, the psychedelics researcher Giorgio Samorini proposed the theory that the fungoid-like paintings in the caves of Tassili are proof of the relationship between humans and psychedelics in the ancient populations of the Sahara, when it was still a verdant land:[14]

One at the most important scenes is to be found in the Tin-Tazarift rock art site, at Tassili, in which we find a series of masked figures in line and hieratically dressed or dressed as dancers surrounded by long and lively festoons of geometrical designs of different kinds... Each dancer holds a mushroom-like object in the right hand and, even more surprising, two parallel lines come out of this object to reach the central part of the head of the dancer, the area of the roots of the two horns. This double line could signify an indirect association or non-material fluid passing from the object held in the right hand and the mind. This interpretation would coincide with the mushroom interpretation if we bear in mind the universal mental value induced by hallucinogenic mushrooms and vegetals, which is often of a mystical and spiritual nature (Dobkin de Rios, 1984:194). It would seem that these lines – in themselves an ideogram which represents something non-material in ancient art – represent the effect that the mushroom has on the human mind... In a shelter in Tin – Abouteka, in Tassili, there is a motif appearing at least twice which associates mushrooms and fish; a unique association of symbols among ethno-mycological cultures... Two mushrooms are depicted opposite each other, in a perpendicular position with regard to the fish motif and near the tail. Not far from here, above, we find other fish which are similar to the aforementioned, but without the side-mushrooms.

— Giorgio Samorini, 1989

This theory was reused by Terence McKenna in his 1992 book Food of the Gods, hypothesizing that the Neolithic culture that inhabited the site used psilocybin mushrooms as part of its religious ritual life, citing rock paintings showing persons holding mushroom-like objects in their hands, as well as mushrooms growing from their bodies.[15] For Henri Lohte who discovered the Tassili caves in the late 1950s, these were obviously secret sanctuaries.[14]

The painting that best supports the mushroom hypothesis is the Tassili mushroom figure Matalem-Amazar where the body of the represented shaman is covered with mushrooms. According to Earl Lee in his book From the Bodies of the Gods: Psychoactive Plants and the Cults of the Dead (2012), this imagery refers to an ancient episode where a "mushroom shaman" was buried while fully-clothed and when unearthed some time later, tiny mushrooms would be growing on the clothes. Earl Lee considered the mushroom paintings at Tassili fairly realistic.[16]

According to Brian Akers, writer for the Mushroom journal, the fungoid rock art in Tassili does not resemble the representations of the Psilocybe hispanica in the Selva Pascuala caves (2015), and he doesn't consider it realistic.[17]

In popular culture

- Tassili is the recording location and the title of a 2011 album by the Tuareg-Berber band Tinariwen.

- Tassili Plain is a track on the 1994 album Natural Wonders of the World in Dub by dub group Zion Train.

Gallery

- Rock-Art, Saharan Cypress and Landscapes of the Tassili

Very high rock columns

Very high rock columns

photograph taken from 30 000 ft Dunes at Tassili n'Ajjer

Dunes at Tassili n'Ajjer Surrounding desert

Surrounding desert Local cypresses

Local cypresses Sandstone rocks and cliffs

Sandstone rocks and cliffs Ritual figure or shaman

Ritual figure or shaman Human figures

Human figures Human figures

Human figures Human figures

Human figures

The rock engravings of Tin-Taghirt

The Tin-Taghirt site is located in the Tassili n'Ajjer between the cities of Dider and Iherir.

An ostrich

An ostrich Sleeping antelope - also found on the reverse of the 1000 Algerian dinar banknote

Sleeping antelope - also found on the reverse of the 1000 Algerian dinar banknote Bubalus antiquus

Bubalus antiquus Footprints

Footprints Human beings

Human beings

Further reading

- Bahn, Paul G. (1998) The Cambridge Illustrated History of Prehistoric Art Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Bradley, R (2000) An archaeology of natural places London, Routledge.

- Bruce-Lockhart, J and Wright, J (2000) Difficult and Dangerous Roads: Hugh Clapperton's Travels in the Sahara and Fezzan 1822-1825

- Chippindale, Chris and Tacon, S-C (eds) (1998) The Archaeology of Rock Art Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Clottes, J. (2002): World Rock Art. Los Angeles: Getty Publications.

- Coulson, D and Campbell, Alec (2001) African Rock Art: Paintings and Engravings on Stone New York, Harry N Abrams.

- Frison-Roche, Roger (1965) Carnets Sahariens Paris, Flammarion

- Holl, Augustin F.C. (2004) Saharan Rock Art, Archaeology of Tassilian Pastoralist Icongraphy

- Lajoux, Jean-Dominique (1977) Tassili n'Ajjer: Art Rupestre du Sahara Préhistorique Paris, Le Chêne.

- Lajoux, Jean-Dominique (1962), Merveilles du Tassili n'Ajjer (The rock paintings of Tassili in translation), Le Chêne, Paris.

- Le Quellec, J-L (1998) Art Rupestre et Prehistoire du Sahara. Le Messak Libyen Paris: Editions Payot et Rivages, Bibliothèque Scientifique Payot.

- Lhote, Henri (1959, reprinted 1973) The Search for the Tassili Frescoes: The story of the prehistoric rock-paintings of the Sahara London.

- Lhote, Henri (1958, 1973, 1992, 2006) À la découverte des fresques du Tassili, Arthaud, Paris.

- Mattingly, D (ed) (forthcoming) The archaeology of the Fezzan.

- Muzzolini, A (1997) "Saharan Rock Art", in Vogel, J O (ed) Encyclopedia of Precolonial Africa Walnut Creek: 347-353.

- Van Albada, A. and Van Albada, A.-M. (2000): La Montagne des Hommes-Chiens: Art Rupestre du Messak Lybien Paris, Seuil.

- Whitley, D S (ed) (2001) Handbook of Rock Art Research New York: Altamira Press.

References

- "La Vallée d'Iherir". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage (11 Oct 2017). "Tassili n'Ajjer". UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- "Rock Art of the Tassili n Ajjer, Algeria" (PDF). Africanrockart.org. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- "Tassili-n-Ajjer". britannica. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- "Tassili n'Ajjer National Park, Djanet". Algeria.com. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- "Tassili National Park, Sahara Algeria". Archmillennium.net. Retrieved 2012-12-16.

- Scheffel, Richard L.; Wernet, Susan J., eds. (1980). Natural Wonders of the World. United States of America: Reader's Digest Association, Inc. pp. 371–372. ISBN 978-0-89577-087-5.

- Pan-African Congress on Prehistory (in French). Kraus Reprint. 1977. p. 68.

Les eaux de pluie ont raviné les crêtes et ont progressivement entaillé les plateaux, creusant des canyons étroits et profonds aux parois à pic, dont la direction générale est Sud-Nord. C'est d'ailleurs ce qui lui a valu le nom de Tassili-n-Ajjer, nom qui vient des mots touaregs : Tasilé = plateau et gir = rivières, ce qui veut dire : le plateau des rivières. == rainwater gutted the ridges and progressively slashed the plateaus, digging narrow, deep canyons with steep walls, whose general direction is South-North. This is what earned it the name of Tassili-n-Ajjer, name that comes from the Tuareg words: Tasilé = plateau and gir= rivers, which means: the plateau of rivers.

- "Crocodiles in the Sahara Desert: An Update of Distribution, Habitats and Population Status for Conservation Planning in Mauritania". PLOS ONE. 25 February 2011.

- "Tassili N'Ajjer (Algeria)". Africanworldheritagesites.org. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- Mercier, Norbert; Le Quellec, Jean-Loïc; Hachid, Malika; Agsous, Safia; Grenet, Michel (July 2012). "OSL dating of quaternary deposits associated with the parietal art of the Tassili-n-Ajjer plateau (Central Sahara)". Quaternary Geochronology. 10: 367–373. doi:10.1016/j.quageo.2011.11.010.

- "Tassili n'Ajer". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- Photography of original, Scielo.org

- Giorgio Samorini, The oldest representations of hallucinogenic mushrooms in the world, Artepreistorica.com, December 2009 (first published in 1992)

- McKenna, Terence (1992). Food of the Gods. United States and Canada: Bantam Books. pp. 72, 73. ISBN 978-0-553-07868-8.

- Earl Lee, From the Bodies of the Gods: Psychoactive Plants and the Cults of the Dead, Simon and Schuster, 16 May 2012 (ISBN 9781594777011)

- Brian Akers, A Cave In Spain Contains the Earliest Known Depictions of Mushrooms, Mushroomthejournal.com, 6 January 2015

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tassili n'Ajjer. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Tassili n'Ajjer Cultural Park. |