Timgad

Timgad (Arabic: تيمقاد; called Thamugas or Thamugadi in old Berber) was a Roman city in the Aurès Mountains of Algeria. It was founded by the Emperor Trajan around CE 100. The full name of the city was Colonia Marciana Ulpia Traiana Thamugadi. Trajan named the city in commemoration of his mother Marcia, eldest sister Ulpia Marciana, and father Marcus Ulpius Traianus.

تمقاد الرومانية | |

Trajan's Arch within the ruins of Timgad. | |

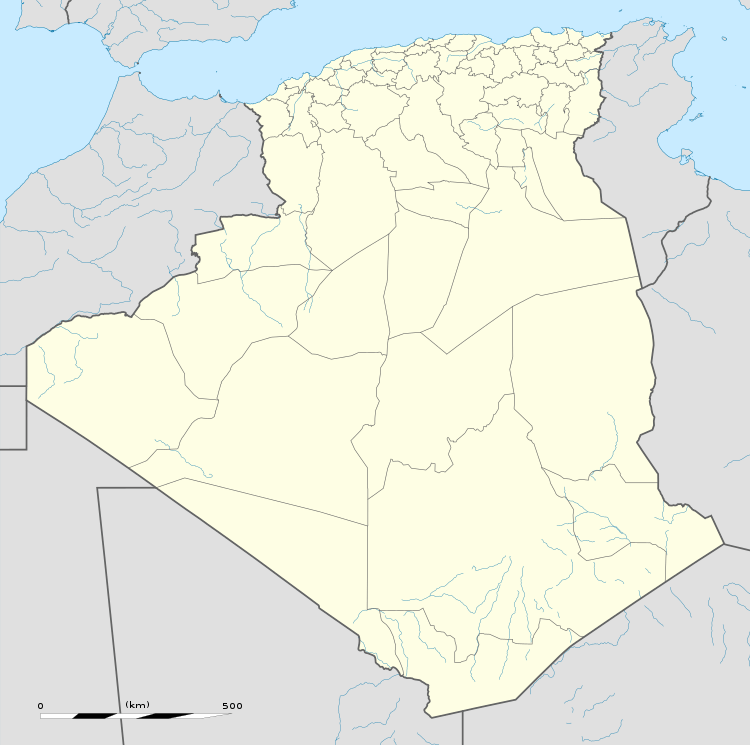

Shown within Algeria | |

| Alternative name |

|

|---|---|

| Location | Batna Province, Algeria |

| Region | Maghreb |

| Coordinates | 35°29′03″N 6°28′07″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | c. 100 |

| Abandoned | 7th century |

| Periods | Roman Empire |

| Official name | Timgad |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iii, iv |

| Designated | 1982 (6th session) |

| Reference no. | 194 |

| State Party | Algeria |

| Region | Arab States |

Located in modern-day Algeria, about 35 km east of the city of Batna, the ruins are noteworthy for representing one of the best extant examples of the grid plan as used in Roman town planning. Timgad was inscribed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1982.

Name

In the former name of Timgad, Marciana Traiana Thamugadi, the first part – Marciana Traiana – is Roman and refers to the name of its founder, Emperor Trajan and his sister Marciana.[1] The second part of the name – Thamugadi – "has nothing Latin about it".[2] Thamugadi is the Berber name of the place where the city was built, to read Timgad plural form of Tamgut, meaning "peak", "summit".[2]

History

The city was founded ex nihilo as a military colony by the emperor Trajan around 100 CE. It was intended to serve primarily as a bastion against the Berbers in the nearby Aures Mountains. It was originally populated largely by Roman veterans and had expanded to over 10,000 residents of Roman, African, as well as Berber descent. Although most of them had never seen Rome before, and Timgad was hundreds of miles away from the Italian city, Trajan invested densely in Roman culture and identity.[3]

The city enjoyed a peaceful existence for the first several hundred years and became a center of Christian activity starting in the 3rd century, and a Donatist center in the 4th century.

In the 5th century, the city was sacked by the Vandals before falling into decline. In 535 CE, the Byzantine general Solomon found the city empty when he came to occupy it during the Vandalic War. In the following century, the city was briefly repopulated as a primarily Christian city before being sacked by Berbers in the 7th century. During the Christian period, Timgad was a diocese which became renowned at the end of the 4th century when Bishop Optat became the spokesman for the Donatist movement. After Optat, Thamugadai had two bishops Gaudentius (Donatist) and Faustinus (Catholic).[4]

Timgad was destroyed at the end of the 5th century by montagnards of the Aurès. The Byzantine Reconquest revived some activities in the city, defended by a fortress built to the south, in 539, reusing blocks removed from Roman monuments. The Arab invasion brought about the final ruin of Thamugadi which ceased to be inhabited after the 8th century CE.[5]

Because no new settlements were founded on the site after the 7th century CE, the city was partially preserved under sand up to a depth of approximately one meter. The encroachment of the Sahara on the ruins was the principal reason why the city is so well preserved.

Travelling the Northern Africa, Scottish explorer James Bruce reached the city ruins on 12 December 1765, being likely the first European to visit the site in centuries and described the city as “a small town, but full of elegant buildings.” In 1790, he published the book Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile, where he described what he has found in Timgad. The book was met with skepticism in Great Britain, until 1875 when Robert Lambert Playfair, Britain’s consul in Algiers, inspired by Bruce's account, visited the site. In 1877 Playfair described Timgad in more detail in his book Travels in the Footsteps of Bruce in Algeria and Tunis. According to Playfair, “These hills are covered with countless numbers of the most interesting mega-lithic remains”.[6] The French colonists took control of the site in 1881, began an investigations and maintained it until 1960. During this period, the site was systematically excavated.[7]

Description

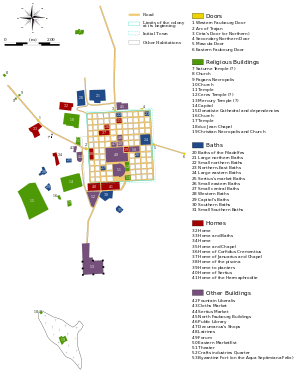

Located at the intersection of six roads, the city was walled but not fortified. Originally designed for a population of around 15,000, the city quickly outgrew its original specifications and spilled beyond the orthogonal grid in a more loosely organized fashion.

At the time of its founding, the area surrounding the city was a fertile agricultural area, about 1000 meters above sea level.

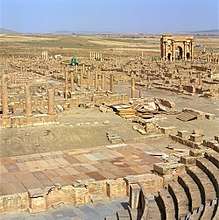

The original Roman grid plan is magnificently visible in the orthogonal design, highlighted by the decumanus maximus (east–west-oriented street) and the cardo (north–south-oriented street) lined by a partially restored Corinthian colonnade. The cardo does not proceed completely through the city but instead terminates in a forum at the intersection with the decumanus.

At the west end of the decumanus rises a 12 m high triumphal arch, called the Arch of Trajan, which was partially restored in 1900. The arch is principally of sandstone, and is of the Corinthian order with three arches, the central one being 11' wide. The arch is also known as the Timgad Arch.

A 3,500-seat theater is in good condition and is used for contemporary productions. The other key buildings include four thermae, a library, and a basilica.

The Capitoline Temple is dedicated to Jupiter and is of approximately the same dimensions as the Pantheon in Rome. Nearby the capitol is a square church, with a circular apse dating from the 7th century CE. One of the sanctuaries featured iconography of (Dea) Africa.[8] Southeast of the city is a large Byzantine citadel built in the later days of the city.

Library

The Library at Timgad was a gift to the Roman people by Julius Quintianus Flavius Rogatianus at a cost of 400,000 sesterces.[9] As no additional information about this benefactor has been unearthed, the precise date of the library's construction remains uncertain. Based on the remaining archaeological evidence, it has been suggested by scholars that it dates from the late 3rd or possibly the 4th century.[9]

The library occupies a rectangle 81 feet (24.69 meters) long by 77 feet (23.47 meters) wide.[9] It consists of a large semi-circular room flanked by two secondary rectangular rooms, and preceded by a U-shaped colonnaded portico surrounding three sides on an open court.[9] The portico is flanked by two long narrow rooms on each side, and the large vaulted hall would have combined the functions of a reading room, stack room, and perhaps a lecture room.[9] Oblong alcoves held wooden shelves along walls that would likely have been complete with sides, backs and doors, based on additional evidence found at the library at Ephesus.[9]

It is possible that free-standing bookcases in the center of the room, as well as a reading desk, might also have been present.[9] While the architecture of the Library at Timgad is not especially remarkable, the discovery of the library is historically important as it shows the presence of a fully developed library system in this Roman city, indicating a high standard of learning and culture. While there is no evidence as to the size of the collection the library harbored, it is estimated that it could have accommodated 3,000 scrolls.[9]

World Heritage Site

Timgad was inscribed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1982.

Gallery

- Ruins of Timgad, February 24, 1928

References

- Haddadou, Mohand Akli (2012). Dictionnaire toponymique et historique de l'Algérie: comportant les principales localités, ainsi qu'un glossaire des mots arabes et berbères entrant dans la composition des noms de lieux (in French). Tizi Ouzou: Achab. p. 529. ISBN 9789947972250.

- Gascou, Jacques. "La politique municipale de l'empire romain en Afrique proconsulaire de Trajan à Septime-Sévère". Publications de l'École française de Rome. 8 (1): 97–100.

- "Buried in Sand for a Millennium: Africa's Roman Ghost City". Messy Nessy Chic. 2020-01-15. Retrieved 2020-05-07.

- Maureen A. Tilley, The Bible in Christian North Africa: The Donatist World (Fortress Press,1997)p135.

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "Timgad". unesco.org.

- Playfair, R. Lambert (Robert Lambert) (1877). Travels in the footsteps of Bruce in Algeria and Tunis : illustrated by facsimiles of his original drawings. Getty Research Institute. London : C. Kegan Paul.

- Montoya, Rubén: The Sahara buried this ancient Roman city—preserving it for centuries at National Geographic, 30 July 2019.

- Akerraz, Aomar (2006). L'Africa romana : mobilità delle persone e dei popoli, dinamiche migratorie, emigrazioni ed immigrazioni nelle province occidentali dell'Impero romano : atti del XVI Convegno di studio, Rabat, 15-19 dicembre (1st ed.). Roma: Carocci. ISBN 8843039903. OCLC 79861941.

- Pfeiffer, H. (1931). The Roman Library at Timgad. Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, 9, 157-165.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Timgad. |

%2C_Algeria_04966r.jpg)

.svg.png)