Echidna

Echidnas (/ɪˈkɪdnə/), sometimes known as spiny anteaters,[1] belong to the family Tachyglossidae in the monotreme order of egg-laying mammals. The four extant species of echidnas and the platypus are the only living mammals that lay eggs and the only surviving members of the order Monotremata.[2] The diet of some species consists of ants and termites, but they are not closely related to the true anteaters of the Americas, which are xenarthrans, along with sloths and armadillos. Echidnas live in Australia and New Guinea.

| Echidnas | |

|---|---|

| |

| Short-beaked echidna | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Monotremata |

| Suborder: | Tachyglossa Gill, 1872 |

| Family: | Tachyglossidae Gill, 1872 |

| Species | |

|

Genus Tachyglossus | |

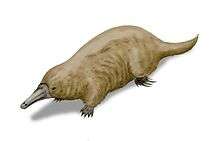

Echidnas evolved between 20 and 50 million years ago, descending from a platypus-like monotreme.[3] This ancestor was aquatic, but echidnas adapted to life on land.[3]

Etymology

The echidnas are named after Echidna, a creature from Greek mythology who was half-woman, half-snake, as the animal was perceived to have qualities of both mammals and reptiles.[4]

Description

Echidnas are medium-sized, solitary mammals covered with coarse hair and spines.[5]

Superficially, they resemble the anteaters of South America and other spiny mammals such as hedgehogs and porcupines. They are usually black or brown in colour. There have been several reports of albino echidnas, their eyes pink and their spines white.[5] They have elongated and slender snouts that function as both mouth and nose. Like the platypus, they are equipped with electrosensors, but while the platypus has 40,000 electroreceptors on its bill, the long-beaked echidna has only 2,000 electroreceptors, and the short-beaked echidna, which lives in a drier environment, has no more than 400 located at the tip of its snout.[6] They have very short, strong limbs with large claws, and are powerful diggers. Their claws on their hind limbs are elongated and curved backwards to help aid in digging. Echidnas have tiny mouths and toothless jaws. The echidna feeds by tearing open soft logs, anthills and the like, and using its long, sticky tongue, which protrudes from its snout, to collect prey. The ears are slits on the sides of their heads that are usually unseen, as they are blanketed by their spines. The external ear is created by a large cartilaginous funnel, deep in the muscle.[5] At 33 °C, the echidna also possess the second lowest active body temperature of all mammals, behind the platypus.

Diet

The short-beaked echidna's diet consists largely of ants and termites, while the Zaglossus (long-beaked) species typically eat worms and insect larvae.[7] The tongues of long-beaked echidnas have sharp, tiny spines that help them capture their prey.[7] They have no teeth, and break down their food by grinding it between the bottoms of their mouths and their tongues.[8] Echidnas' faeces are 7 cm (3 in) long and are cylindrical in shape; they are usually broken and unrounded, and composed largely of dirt and ant-hill material.[8]

Habitat

Echidnas do not tolerate extreme temperatures; they use caves and rock crevices to shelter from harsh weather conditions. Echidnas are found in forests and woodlands, hiding under vegetation, roots or piles of debris. They sometimes use the burrows of animals such as rabbits and wombats. Individual echidnas have large, mutually overlapping territories.[8]

Despite their appearance, echidnas are capable swimmers. When swimming, they expose their snout and some of their spines, and are known to journey to water in order to groom and bathe themselves.[9]

Anatomy

Echidnas and the platypus are the only egg-laying mammals, known as monotremes. The average lifespan of an echidna in the wild is estimated around 14–16 years. When fully grown, a female can weigh up to 4.5 kilograms (9.9 lb), and a male can weigh up to 6 kilograms (13 lb).[8] The echidnas' sex can be inferred from their size, as males are 25% larger than females on average. The reproductive organs also differ, but both sexes have a single opening called a cloaca, which they use to urinate, release their faeces and to mate.[5]

Male echidnas have non-venomous spurs on the hind feet.[10]

The neocortex makes up half of the echidna's brain,[11] compared to 80% of a human brain.[12][13] Due to their low metabolism and accompanying stress resistance, echidnas are long-lived for their size; the longest recorded lifespan for a captive echidna is 50 years, with anecdotal accounts of wild individuals reaching 45 years.[14] Contrary to previous research, the echidna does enter REM sleep, but only when the ambient temperature is around 25 °C (77 °F). At temperatures of 15 °C (59 °F) and 28 °C (82 °F), REM sleep is suppressed.[15]

Reproduction

The female lays a single soft-shelled, leathery egg 22 days after mating, and deposits it directly into her pouch. An egg weighs 1.5 to 2 grams (0.05 to 0.07 oz)[16] and is about 1.4 centimetres (0.55 in) long. While hatching, the baby echidna opens the leather shell with a reptile-like egg tooth.[17] Hatching takes place after 10 days of gestation; the young echidna, called a puggle,[18][19] born larval and fetus-like, then sucks milk from the pores of the two milk patches (monotremes have no nipples) and remains in the pouch for 45 to 55 days,[20] at which time it starts to develop spines. The mother digs a nursery burrow and deposits the young, returning every five days to suckle it until it is weaned at seven months. Puggles will stay within their mother's den for up to a year before leaving.[8]

Male echidnas have a four-headed penis.[21] During mating, the heads on one side "shut down" and do not grow in size; the other two are used to release semen into the female's two-branched reproductive tract. Each time it copulates, it alternates heads in sets of two.[22][23] When not in use, the penis is retracted inside a preputial sac in the cloaca. The male echidna's penis is 7 centimetres (2.8 in) long when erect, and its shaft is covered with penile spines.[24] These may be used to induce ovulation in the female.[25] It is a challenge to study the echidna in its natural habitat and they show no interest in mating while in captivity. Prior to 2007, no one had ever seen an echidna ejaculate. There have been previous attempts, trying to force the echidna to ejaculate through the use of electrically stimulated ejaculation in order to obtain semen samples but has only resulted in the penis swelling.[23] Breeding season begins in late June and extends through September. Males will form lines up to ten individuals long, the youngest echidna trailing last, that follow the female and attempt to mate. During a mating season an echidna may switch between lines. This is known as the "train" system.[8]

Threats

Echidnas are very timid animals. When they feel endangered they attempt to bury themselves or if exposed they will curl into a ball similar to that of a hedgehog, both methods using their spines to shield them. Strong front arms allow echidnas to continue to dig themselves in whilst holding fast against a predator attempting to remove them from the hole. Although they have a way to protect themselves, the echidnas still face many dangers. Some predators include feral cats, foxes, domestic dogs and goannas. Snakes pose a large threat to the echidna species because they slither into their burrows and prey on the young spineless puggles. Some precautions that can be taken include keeping the environment clean by picking up litter and causing less pollution, planting vegetation for echidnas to use as shelter, supervising pets, reporting hurt echidnas or just leaving them undisturbed. Merely grabbing them may cause stress, and picking them up improperly may even result in injury.[8]

Evolution

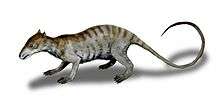

The first divergence between oviparous (egg-laying) and viviparous (offspring develop internally) mammals is believed to have occurred during the Triassic period.[26] However, there is still some disagreement on this estimated time of divergence. Though most findings from genetics studies (especially those concerning nuclear genes) are in agreement with the paleontological findings, some results from other techniques and sources, like mitochondrial DNA, are in slight disagreement with findings from fossils.[27]

Molecular clock data suggest echidnas split from platypuses between 19 and 48 million years ago, and that platypus-like fossils dating back to over 112.5 million years ago therefore represent basal forms, rather than close relatives of the modern platypus.[3] This would imply that echidnas evolved from water-foraging ancestors that returned to living completely on the land, even though this put them in competition with marsupials. Further evidence of possible water-foraging ancestors can be found in some of the echidna's phenotypic traits as well. These traits include hydrodynamic streamlining, dorsally projecting hind limbs acting as rudders, and locomotion founded on hypertrophied humeral long-axis rotation, which provides a very efficient swimming stroke.[3] Consequently, oviparous reproduction in monotremes may have given them an advantage over marsupials, a view consistent with present ecological partitioning between the two groups.[3] This advantage could as well be in part responsible for the observed associated adaptive radiation of echidnas and expansion of the niche space, which together contradict the fairly common assumption of halted morphological and molecular evolution that continues to be associated with monotremes. Furthermore, studies of mitochondrial DNA in platypuses have also found that monotremes and marsupials are most likely sister taxa. It also implies that any shared derived morphological traits between marsupials and placental mammals either occurred independently from one another or were lost in the lineage to monotremes.[28]

Taxonomy

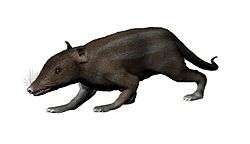

Echidnas are classified into three genera.[29] The genus Zaglossus includes three extant species and two species known only from fossils, while only one extant species from the genus Tachyglossus is known. The third genus, Megalibgwilia, is known only from fossils.

Zaglossus

The three living Zaglossus species are endemic to New Guinea.[29] They are rare and are hunted for food. They forage in leaf litter on the forest floor, eating earthworms and insects. The species are

- Western long-beaked echidna (Z. bruijni), of the highland forests;

- Sir David's long-beaked echidna (Z. attenboroughi), discovered by western science in 1961 (described in 1998) and preferring a still higher habitat;

- Eastern long-beaked echidna (Z. bartoni), of which four distinct subspecies have been identified.

The two fossil species are

Tachyglossus

The short-beaked echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus) is found in southern, southeast and northeast New Guinea, and also occurs in almost all Australian environments, from the snow-clad Australian Alps to the deep deserts of the Outback, essentially anywhere ants and termites are available. It is smaller than the Zaglossus species, and it has longer hair.

Despite the similar dietary habits and methods of consumption to those of an anteater, there is no evidence supporting the idea that echidna-like monotremes have been myrmecophagic (ant or termite-eating) since the Cretaceous. The fossil evidence of invertebrate-feeding bandicoots and rat-kangaroos, from around the time of the platypus–echidna divergence and pre-dating Tachyglossus, show evidence that echidnas expanded into new ecospace despite competition from marsupials.[30]

Megalibgwilia

The genus Megalibgwilia is known only from fossils:

- M. ramsayi from Late Pleistocene sites in Australia;

- M. robusta from Miocene sites in Australia.

As food

Aboriginal Australians regard the echidna as a food delicacy.[31]

The Kunwinjku people of Western Arnhem Land call the echnidna ngarrbek[32], and regard it as a prized food and 'good medicine' (Reverend Peterson Nganjmirra, personal comment[33]). Echidna is hunted at night. After being gutted it is filled with hot stones and bush herbs namely the leaves of mandak (Persoonia falcata)[34]. According to Larrakia elders Una Thompson and Stephanie Thompson Nganjmirra, when captured echidna is carried attached to the wrist like a thick bangle.

In popular culture

- The echidna appears on the reverse of the Australian five-cent coin.[35]

- Knuckles the Echidna is a popular character from the Sonic the Hedgehog video game franchise, debuting in Sonic the Hedgehog 3.

- Some have argued that the Niffler—a creature from the Harry Potter universe which steals shiny objects—was based on the echidna.[36]

References

- "Short-Beaked Echidna, Tachyglossus aculeatus". Park & Wildlife Service Tasmania. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- Stewart, Doug (April–May 2003). "The Enigma of the Echidna". National Wildlife. Archived from the original on 29 April 2012.

- Phillips, MJ; Bennett, TH; Lee, MS (October 2009). "Molecules, morphology, and ecology indicate a recent, amphibious ancestry for echidnas". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 (40): 17089–94. doi:10.1073/pnas.0904649106. PMC 2761324. PMID 19805098.

- "echidna". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- Augee, Michael; Gooden, Brett; Musser, Anne (2006). Echidna : extraordinary egg-laying mammal (2nd ed.). CSIRO. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-643-09204-4.

- "Electroreception in fish, amphibians and monotremes". Map of Life. 7 July 2010.

- "Zaglossus bruijni". AnimalInfo.org.

- Carritt, Rachel. "Echidnas: Helping them in the wild" (PDF). NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- "Short-beaked Echidna". Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water, and Environment. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- Griffiths, Mervyn (1978). The biology of the monotremes. New York: Academic Press. ISBN 0123038502.

- Gill, Victoria (19 November 2012). "Are these animals too 'ugly' to be saved?". BBC News.

- Dunbar, R.I.M. (1993). "Coevolution of neocortical size, group size and language in humans". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 16 (4): 681–735. doi:10.1017/S0140525X00032325.

- Dunbar, R.I.M. "The Social Brain Hypothesis" (PDF). University of Colorado at Boulder, Department of Psychology and Neuroscience. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- Cason, M. (2009). "Tachyglossus aculeatus". Animal Diversity. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- Nicol, SC; Andersen, NA; Phillips, NH; Berger, BJ (March 2000). "The echidna manifests typical characteristics of rapid eye movement sleep". Neurosci. Lett. 283 (1): 49–52. doi:10.1016/S0304-3940(00)00922-8. PMID 10729631.

- "Echidnas". wildcare.org.au. Wildcare Australia. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- O'Neil, Dennis. "Echidna Reproduction" 12 February 2011. Retrieved on 17 June 2015.

- Kuruppath, Sanjana; Bisana, Swathi; Sharp, Julie A; Lefevre, Christophe; Kumar, Satish; Nicholas, Kevin R (11 August 2012). "Monotremes and marsupials: Comparative models to better understand the function of milk". Journal of Biosciences. 37 (4): 581–588. doi:10.1007/s12038-012-9247-x. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30047989.

Developmental stages of echidna: (A) Echidna eggs; (B) Echidna puggle hatching from egg...

- Calderwood, Kathleen (18 November 2016). "Taronga Zoo welcomes elusive puggles". ABC News. Sydney. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- "Short-beaked echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus)". Arkive.org. Archived from the original on 13 August 2009. Retrieved 21 October 2009.

- Grützner, F., B. Nixon, and R. C. Jones. "Reproductive biology in egg-laying mammals." Sexual Development 2.3 (2008): 115-127.

- Johnston, Steve D.; et al. (2007). "One‐Sided Ejaculation of Echidna Sperm Bundles" (PDF). The American Naturalist. 170 (6): E162–E164. doi:10.1086/522847. JSTOR 10.1086/522847. PMID 18171162.

- Shultz, N. (26 October 2007). "Exhibitionist spiny anteater reveals bizarre penis". New Scientist. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- Larry Vogelnest; Rupert Woods (18 August 2008). Medicine of Australian Mammals. Csiro Publishing. ISBN 978-0-643-09928-9. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- Hayssen, V.D.; Van Tienhoven, A. (1993). "Order Monotremata, Family Tachyglossidae". Asdell's Patterns of Mammalian Reproduction: A Compendium of Species-specific Data. Cornell University Press. pp. 8–9. ISBN 0-8014-1753-8.

- Rowe T, Rich TH, Vickers-Rich P, Springer M, Woodburne MO (2008). "The oldest platypus and its bearing on divergence timing of the platypus and echidna clades". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 (4): 1238–42. doi:10.1073/pnas.0706385105. PMC 2234122. PMID 18216270.

- Musser AM (2003). "Review of the monotreme fossil record and comparison of palaeontological and molecular data". Comp. Biochem. Physiol., Part a Mol. Integr. Physiol. 136 (4): 927–42. doi:10.1016/s1095-6433(03)00275-7. PMID 14667856.

- Janke A, Xu X, Arnason U (1997). "The complete mitochondrial genome of the wallaroo (Macropus robustus) and the phylogenetic relationship among Monotremata, Marsupialia, and Eutheria". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94 (4): 1276–81. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.4.1276. PMC 19781. PMID 9037043.

- Flannery, T.F.; Groves, C.P. (1998). "A revision of the genus Zaglossus (Monotremata, Tachyglossidae), with description of new species and subspecies". Mammalia. 62 (3): 367–396. doi:10.1515/mamm.1998.62.3.367.

- Phillips, Matthew; Bennett, T.; Lee, Michael (2010). "Reply to Camens: How recently did modern monotremes diversify?". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 (4): E13. doi:10.1073/pnas.0913152107. PMC 2824408.

- SIMMONDS, Peter Lund (1859). The Curiosities of Food: Or Dainties and Delicacies of Different Nations Obtained from the Animal Kingdom. Bentley. p. 75.

Aboriginal echidna delicacy.

- Garde, Murray. "ngarrbek". Bininj Kunwok Online Dictionary. Bininj Kunwok Regional Language Centre. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- Goodfellow, D. (1993). Fauna of Kakadu and the Top End. Wakefield Press. p. 17. ISBN 1862543062.

- Garde, Murray. "mandak". Bininj Kunwok Online Dictionary. Bininj Kunwok Regional Language Centre. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- "Royal Australian Mint: 5 cents". Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- Kyriazis, Stefan (23 November 2016). "What is an echidna puggle? Meet the REAL Fantastic Beasts Niffler". Daily Express. London. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

Bibliography

- Ronald M. Nowak (1999), Walker's Mammals of the World (6th ed.), Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-5789-9, LCCN 98023686

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Echidna. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Tachyglossidae |

- http://paulbartlett.zenfolio.com/echidnatachyglossusaculeatus

- Stewart, Doug (April 2003). "The Enigma of the Echidna". National Wildlife. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- Parker, J. (1 June 2000). "Echidna Love Trains". ABC Science. Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- Rismiller, Peggy (2005). "Echidna research, Kangaroo island". Pelican Lagoon Research & Wildlife Centre.

- "Tachyglossidae". NCBI Taxonomy Browser. 9259.