Schowalteria

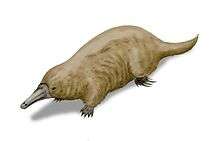

Schowalteria is a genus of extinct mammal from the Cretaceous of Canada. It is the earliest known representative of Taeniodonta, a specialised lineage of non-placental eutherian mammals otherwise found in Paleocene and Eocene deposits. It is notable for its large size, being among the largest of Mesozoic mammals,[1][2] as well as its speciation towards herbivory, which in some respects exceeds that of its later relatives.[3]

| Schowalteria | |

|---|---|

Fossil | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Suborder: | |

| Genus: | †Schowalteria R. C. Fox and B. G. Naylor. 2003 |

| Species | |

| |

Description

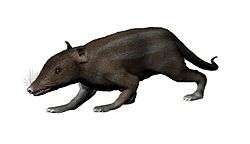

Currently, Schowalteria is considered to be a monotypic genus, with only one species, S. clemensi. It is known from only one skull. Schowalteria shares some speciations with later taeniodonts, namely similar canine and incisor morphology, similar facial proportions and zygomatic arch construction, though unlike them its occlusal surface is worn nearly completely flat, and the wear facet completely encompasses the paracone and metacone, leaving only an outline of the buccal side of the bases of these cusps remaining, differing radically from the more "normal" teeth wearing patterns of other taenidonts.[3] Based on the skull's proportions, it was initially comparared in size to Didelphodon vorax, making it one of the largest mammals of the Mesozoic at the time of its discovery,[1] and posterior measurements have cited larger sizes; Anne Weil posits a range similar (though not confirmed) to Repenomamus giganticus,[4] while posterior analysis showcase it to be as large as latter taeniodonts.[5]

Range

Schowalteria occurs in the Trochu deposits of Alberta, dating to the Maastrichtian stage of the Cretaceous period. This site is part of the larger Edmonton Group, that probably represented a warm, temperate environment. Mammal remains are very common in this site, such as various metatherians and multituberculates.

Classification

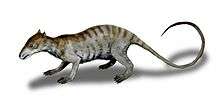

Schowalteria is a taeniodont eutherian. It was initially recovered as a fairly derived member related to stylinodonts,[1] but more recent examinations show it to be a more basal species within the group, less related to them than Onychodectes.[3]

Biology

In spite of being a basal taeniodont, Schowalteria is fairly derived, perhaps more so than later taenidonts. It shares with them similar speciations towards herbivory and possibly fossoriality,[1] but unlike them it also possesses evidence of transverse (ungulate-like) mastication, making it even more specialised towards processing vegetation.[3]

As one of the largest mammals of its time period and a rather specialised herbivore, Schowalteria was a rather spectacular species among the dinosaur-rich faunas of the end of the Cretaceous.

References

- Fox, Richard C.; Naylor, Bruce G. (2003). "A Late Cretaceous taeniodont (Eutheria, Mammalia) from Alberta, Canada". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie. 229 (3).

- Weil, Anne (2005). "Living large in the Cretaceous". Nature. 433. doi:10.1038/43311b.

- Williamson, T. E.; Brusatte, S. L. (2013). Viriot, Laurent (ed.). "New Specimens of the Rare Taeniodont Wortmania (Mammalia: Eutheria) from the San Juan Basin of New Mexico and Comments on the Phylogeny and Functional Morphology of "Archaic" Mammals". PLoS ONE. 8 (9): e75886. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0075886. PMC 3786969. PMID 24098738.

- Weil, Anne. "Mammalian palaeobiology: Living large in the Cretaceous". Nature. 433: 116–117. doi:10.1038/433116b.

- Rook, Deborah L.; Paul Hunter, John. "Phylogeny of the Taeniodonta: Evidence from Dental Characters and Stratigraphy". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (2): 422–427. doi:10.1080/02724634.2011.550364.