Thylacosmilidae

Thylacosmilidae is an extinct family of metatherian predators, related to the modern marsupials, which lived in South America between the Miocene and Pliocene epochs. Like other South American mammalian predators that lived prior to the Great American Biotic Interchange, these animals belonged to the order Sparassodonta, which occupied the ecological niche of many eutherian mammals of the order Carnivora from other continents. The family's most notable feature are the elongated, laterally flattened fangs, which is a remarkable evolutionary convergence with other saber-toothed mammals like Barbourofelis and Smilodon.[1]

| Thylacosmilidae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Thylacosmilus skull | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | †Sparassodonta |

| Family: | †Thylacosmilidae Riggs 1933 |

| Genera | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Thylacosmilinae Riggs 1933 | |

Taxonomic history

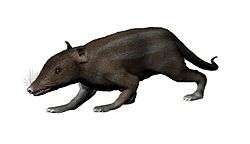

The family Thylacosmilidae was originally erected by Riggs in 1933, to accommodate Thylacosmilus, found in the Pliocene Brochero Formation of Argentina. Later, the family was demoted to a subfamily, as Thylacosmilinae, within Borhyaenidae, a group of superficially canid-like sparassodonts, under the assumption that Thylacosmilus was merely a late and specialized borhyaenid. Later, with the discovery of fragmentary specimens of new sparassodonts related to Thylacosmilus from Miocene and Pliocene strata, Thylacosmilidae was promoted back to familial status.[1]

In 1997, a second genus and species of thylacosmilid was described from the Laventan Honda Group at the Lagerstätte La Venta in Colombia, Anachlysictis gracilis. This animal, less specialized than Thylacosmilus, was the first indication that the family origins dates back to before the end of the Miocene. In fact, the anatomy of Anachlysictis' molar teeth suggests a closer relationship with basal sparassodonts like Hondadelphys than with advanced sparassodonts like Borhyaena.[2][3] Also, additional materials of a small predatory sparassodont of Colombia have been found, which has certain features diagnostic of thylacosmilids, but much less specialized, as well as indeterminate remains in Uruguay and the Argentinean Patagonia, from the early Pliocene, has been tentatively assigned to family.[1] Forasiepi and Carlini in 2010 unveiled a third genus and species, Patagosmilus goini, from the Collón Cura Formation of Argentina from the mid-Miocene, with characteristics intermediate between Anachlysictis and Thylacosmilus.[1]

Description

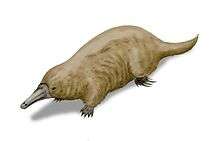

The family is perhaps the best known among sparassodonts because their dental and cranial specializations, which is superficially similar to that of the saber-toothed cats, often cited as an example of convergent evolution between placental and metatherian mammals. However, there were several differences between thylacosmilids and the other saber-toothed mammals, and these unique traits diagnose the family: unique traits include canine teeth that grew continuously, less specialized carnassial molars and tremendous, flange-like outgrowths of the lower jaw that protected the saber-teeth.

In Thylacosmilus, the last and most specialized known member, the incisors are very small and the lower teeth are poorly developed, and tack-shaped; in the other genera these elements are unknown. In Thylacosmilus, the upper incisors are unknown other than by wear indentations on the lower incisors, as no premaxilla has ever been found complete in this genus.[4] Another evolutionary trend in families is the progressive reduction of masseter and temporal muscles, resulting in relatively weak bites, but compensated by the increase in the size of the neck muscles to lower the head and the fangs into the necks of their prey.[5] Fossils of Thylacosmilus forelimbs, the only reported for this group, indicate that animals were not fast runners, and were in turn adapted to exert force in order to subdue their prey, helping with their semiopposable thumb.[6]

A recent study has since proposed a lack of analogy between thylacosmilids and saber toothed eutherians, speculating that rather than using the fangs to pierce prey they were instead used to open up corpses. Their lack of incisors and crushing molars suggest an entrail-based diet, and irrigated bone on the maxillae suggests some sort of extensive, soft tissue-based structure.[7]

References

- Analía M. Forasiepi & Alfredo A. Carlini (2010). A new thylacosmilid (Mammalia, Metatheria, Sparassodonta) from the Miocene of Patagonia, Argentina. Zootaxa 2552: 55–68

- Goin, F.J. (1997) New clues for understanding Neogene marsupial radiations. In: Kay, R.F., Madden, R.H., Cifelli, R.L. & Flynn, J. (Eds.), A History of the Neotropical Fauna -Vertebrate Paleobiology of the Miocene in Colombia. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, pp. 185–204.

- Goin, F.J. 2003. Early marsupial radiations in South America. En: M. Jones, C. Dickman y M. Archer (eds.), Predators with Pouches, The Biology of Carnivorous Marsupials, CSIRO Publishing, Australia, pp. 30-42.

- Anton, Mauricio (2013). Sabertooth.

- Christine Argot (2004): Evolution of South American mammalian predators (Borhyaenoidea): anatomical and palaeobiological implications. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2004, 140, 487–521.

- Christine Argot (2004): Functional-adaptive features and palaeobiologic implications of the postcranial skeleton of the late Miocene sabretooth borhyaenoid Thylacosmilus atrox (Metatheria), Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology, 28:1, 229-266.

- https://peerj.com/articles/9346/