Eid al-Adha

Eid al-Adha (Arabic: عيد الأضحى, romanized: ʿīd al-ʾaḍḥā, lit. 'Feast of the Sacrifice', IPA: [ʕiːd alˈʔadˤħaː]) is the last of the two Islamic holidays celebrated worldwide each year (the other being Eid al-Fitr), and considered the holier of the two. It honours the willingness of Ibrahim (Abraham) to sacrifice his son Ismael as an act of obedience to God's command. (The Jewish and Christian religions believe that according to Genesis 22:2, Abraham took his son Isaac to sacrifice). Before Ibrahim could sacrifice his son, however, God provided a lamb to sacrifice instead. In commemoration of this intervention, an animal (usually a sheep) is sacrificed ritually. One third of its meat is consumed by the family offering the sacrifice, while the rest is distributed to the poor and needy. Sweets and gifts are given, and extended family are typically visited and welcomed.[4]

| Eid al-Azha | |

|---|---|

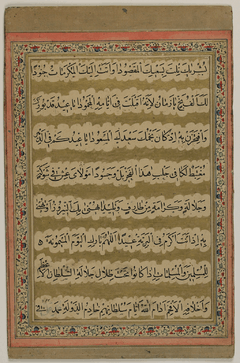

Calligraphic fragment dated to 1729–30 displaying blessings for Eid al-Adha in Arabic | |

| Official name | عيد الأضحى Eid al-Adha Template:عید قربان Eid_e Qorbān |

| Observed by | Muslims and Druze |

| Type | Islamic |

| Significance |

|

| Observances | Eid prayers, animal sacrifice, charity, social gatherings, festive meals, gift-giving |

| Begins | 10 Dhu al-Hijjah nbm, |

| Ends | 13 Dhu al-Hijjah |

| Date | 10 Dhu al-Hijjah |

| 2019 date | 11 August[1][2] |

| 2020 date | 31 July[3] |

| 2021 date | 20 July |

| Related to | Hajj; Eid al-Fitr |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic culture |

|---|

| Architecture |

| Art |

|

| Dress |

| Holidays |

|

| Literature |

|

| Music |

| Theatre |

|

In the Islamic lunar calendar, Eid al-Adha falls on the 10th day of Dhu al-Hijjah, and lasts for four days. In the international (Gregorian) calendar, the dates vary from year to year shifting approximately 11 days earlier each year.

Etymology

The Arabic word عيد (ʿīd) means 'festival', 'celebration', 'feast day', or 'holiday'. It itself is a triliteral root عيد with associated root meanings of "to go back, to rescind, to accrue, to be accustomed, habits, to repeat, to be experienced; appointed time or place, anniversary, feast day."[5][6] Arthur Jeffery contests this etymology, and believes the term to have been borrowed into Arabic from Syriac, or less likely Targumic Aramaic.[7]

The words أضحى (aḍḥā) and قربان (qurbān) are synonymous in meaning 'sacrifice' (animal sacrifice), 'offering' or 'oblation'. The first word comes from the triliteral root ضحى (ḍaḥḥā) with associated meanings of "immolate ; offer up ; sacrifice ; victimize."[8] No occurrence of this root with a meaning related to sacrifice occurs in the Qur'an[5] but in the Hadith literature. Arab Christians use the term to mean the Eucharistic host. The second word derives from the triliteral root قرب (qaraba) with associated meanings of "closeness, proximity... to moderate; kinship...; to hurry; ...to seek, to seek water sources...; scabbard, sheath; small boat; sacrifice."[6] Arthur Jeffery recognizes the same Semitic root, but believes the sense of the term to have entered Arabic through Aramaic.[7] Compare Hebrew korban קָרבן (qorbān).

Other languages

In languages other, the name is often simply translated into the local language, such as Eid Qurban (Persian: عيد قربان), Qurban Bayrami (Azerbaijani: Qurban Bayramı), Tafaska tameqrant (Berber languages: Amazigh), English Feast of the Sacrifice, German Opferfest, Dutch Offerfeest, Romanian Sărbătoarea Sacrificiului, and Hungarian Áldozati ünnep. In Spanish it is known as Fiesta del Cordero[9] or Fiesta del Borrego (both meaning "festival of the lamb"). In Kurdish it is known as (Cejna Qurbanê / جەژنی قوربان). It is also known as Eid Qurban (عید قربان) in Persian speaking countries such as Afghanistan and Iran, Kurban Bayramı[10][11] in Turkey, Qurban Bayramı in Azerbaijan, কোরবানীর ঈদ in Bangladesh, as عید الكبير the big Feast in the Maghreb, as Iduladha, Hari Raya Aidiladha, Hari Raya Haji or Hari Raya Korban in Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and the Philippines, as بکرا عید "Goat Eid" or بڑی عید "Greater Eid" in India and Pakistan, Bakara Eid in Trinidad and Tobago, as 𞤔𞤓𞥅𞤂𞤁𞤉 𞤁𞤌𞤐𞤑𞤋𞤐 or Juulde Donkin in the Fulfulde language, as Tabaski or Tobaski in The Gambia, Guinea, and Senegal (most probably borrowed from the Serer language – and an ancient Serer religious festival[12][13][14][15]), and as Odún Iléyá by the Yorúbà people of Nigeria.[16][17][18][19]

The following names are used as other names of Eid al-Adha:

- عیدالاضحیٰ (transliterations of the Arabic name)[20] is used in Urdu, Hindi, Assamese, Bengali, Gujarati, and Austronesian languages such as Malay and Indonesian.

- العيد الكبير meaning "Greater Eid" (the "Lesser Eid" being Eid al-Fitr)[21] is used in Yemen, Syria, and North Africa (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt). Local language translations are used لوی اختر in Pashto, Kashmiri (Baed Eid), Urdu and Hindi (Baṛī Īd), বড় ঈদ in Bengali, Tamil (Peru Nāl, "Great Day") and Malayalam (Bali Perunnal, "Great Day of Sacrifice") as well as Manding varieties in West Africa such as Bambara, Maninka, Jula etc. (ߛߊߟߌߓߊ Seliba, "Big/great prayer").

- عید البقرة (eid al-baqara) meaning "the Feast of Cows (also sheep or goats)" is used in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the Middle East. Although the word بقرة properly means a cow, it is also semantically extended to mean all livestock, especially sheep or goats. This extension is used in Hindi and Urdu as a very similar name ईद-उल-अज़हा (īd-ul-azhā, 'the Feast of goat') is used for the occasion.

- The Feast of Sacrifice is used in Uzbekistan.

- The Hajj Feast[16][17] is used in Malaysian and Indonesian, in the Philippines.

- Big Sallah in Nigeria, as it is considered to be holier than Eid al-Fitr (which is locally known as the "Small Sallah").[22] "Ram Sallah" is also used, as it refers to the rams that are being sacrificed on that day.

Origin

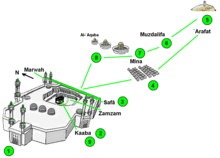

One of the main trials of Abraham's life was to face the command of God by sacrificing his beloved son.[23] In Islam, Abraham kept having dreams that he was sacrificing his son Ishmael. Abraham knew that this was a command from God and he told his son, as stated in the Quran "Oh son, I keep dreaming that I am slaughtering you", Ishmael replied "Father, do what you are ordered to do." Abraham prepared to submit to the will of God and prepared to slaughter his son as an act of faith and obedience to God.[24] During this preparation, Shaytaan tempted Abraham and his family by trying to dissuade them from carrying out God's commandment, and Abraham drove Satan away by throwing pebbles at him. In commemoration of their rejection of Satan, stones are thrown at symbolic pillars Stoning of the Devil during Hajj rites.[25]

Acknowledging that Abraham was willing to sacrifice what is dear to him, God the almighty honoured both Abraham and Ishmael. Angel Jibreel (Gabriel) called Abraham "O' Abraham, you have fulfilled the revelations." and a lamb from heaven was offered by Angel Gabriel to prophet Abraham to slaughter instead of Ishmael. Muslims worldwide celebrate Eid al Adha to commemorate both the devotion of Abraham and the survival of Ishmael.[26][27][28]

This story is known as the Akedah in Judaism (Binding of Isaac) and originates in the Torah,[29] the first book of Moses (Genesis, Ch. 22). The Quran refers to the Akedah as follows:[30]

100 "O my Lord! Grant me a righteous (son)!"

101 So We gave him the good news of a boy ready to suffer and forbear.

102 Then, when (the son) reached (the age of) (serious) work with him, he said: "O my son! I see in vision that I offer thee in sacrifice: Now see what is thy view!" (The son) said: "O my father! Do as thou art commanded: thou will find me if Allah (God) so wills one practicing Patience and Constancy!"

103 So when they had both submitted their wills (to Allah), and he had laid him prostrate on his forehead (for sacrifice),

104 We called out to him "O Abraham!

105 "Thou hast already fulfilled the vision!" – thus indeed do We reward those who do right.

106 For this was obviously a trial–

107 And We ransomed him with a momentous sacrifice:

108 And We left (this blessing) for him among generations (to come) in later times:

109 "Peace and salutation to Abraham!"

110 Thus indeed do We reward those who do right.

111 For he was one of our believing Servants.

112 And We gave him the good news of Isaac – a prophet – one of the Righteous.

The word "Eid" appears once in Al-Ma'ida, the fifth sura of the Quran, with the meaning "solemn festival".[32]

Purpose of sacrifice in Eid al-Adha

The purpose of sacrifice in Eid al-Adha is not about shedding of blood just to satisfy Allah. It is about sacrificing something devotees love the most to show their devotion to Allah.[33] It is also obligatory to share the meat of the sacrificed animal in three equivalent parts – for family, for relatives and friends, and for poor people.[34] The celebration has a clear message of devotion, kindness and equality. It is said that the meat will not reach to Allah, nor will the blood, but what reaches him is the devotion of devotees.

Eid prayers

Devotees offer the Eid al-Adha prayers at the mosque. The Eid al-Adha prayer is performed any time after the sun completely rises up to just before the entering of Zuhr time, on the 10th of Dhu al-Hijjah. In the event of a force majeure (e.g. natural disaster), the prayer may be delayed to the 11th of Dhu al-Hijjah and then to the 12th of Dhu al-Hijjah.[35]

Eid prayers must be offered in congregation. Participation of women in the prayer congregation varies from community to community.[36] It consists of two rakats (units) with seven takbirs in the first Raka'ah and five Takbirs in the second Raka'ah. For Shia Muslims, Salat al-Eid differs from the five daily canonical prayers in that no adhan (call to prayer) or iqama (call) is pronounced for the two Eid prayers.[37][38] The salat (prayer) is then followed by the khutbah, or sermon, by the Imam.[39]

At the conclusion of the prayers and sermon, Muslims embrace and exchange greetings with one another (Eid Mubarak), give gifts and visit one another. Many Muslims also take this opportunity to invite their friends, neighbours, co-workers and classmates to their Eid festivities to better acquaint them about Islam and Muslim culture.[40]

Traditions and practices

During Eid al-Adha, distributing meat amongst the people, chanting the takbir out loud before the Eid prayers on the first day and after prayers throughout the four days of Eid, are considered essential parts of this important Islamic festival.[41]

The takbir consists of:[42]

الله أكبر الله أكبر |

Allāhu akbar, allāhu akbar |

Men, women, and children are expected to dress in their finest clothing to perform Eid prayer in a large congregation in an open waqf ("stopping") field called Eidgah or mosque. Affluent Muslims who can afford it sacrifice their best halal domestic animals (usually a camel, goat, sheep, or ram depending on the region) as a symbol of Abraham's willingness to sacrifice his only son.[43] The sacrificed animals, called aḍḥiya (Arabic: أضحية), known also by the Perso-Arabic term qurbāni, have to meet certain age and quality standards or else the animal is considered an unacceptable sacrifice.[44] In Pakistan alone nearly ten million animals are slaughtered on Eid days costing over $2 billion.[45]

The meat from the sacrificed animal is preferred to be divided into three parts. The family retains one-third of the share; another third is given to relatives, friends, and neighbors; and the remaining third is given to the poor and needy.[43]

Muslims wear their new or best clothes. Women cook special sweets, including ma'amoul (filled shortbread cookies) and samosas. They gather with family and friends.[35]

Eid al-Adha in the Gregorian calendar

While Eid al-Adha is always on the same day of the Islamic calendar, the date on the Gregorian calendar varies from year to year since the Islamic calendar is a lunar calendar and the Gregorian calendar is a solar calendar. The lunar calendar is approximately eleven days shorter than the solar calendar.[46] Each year, Eid al-Adha (like other Islamic holidays) falls on one of about two to four Gregorian dates in parts of the world, because the boundary of crescent visibility is different from the International Date Line.[47]

The following list shows the official dates of Eid al-Adha for Saudi Arabia as announced by the Supreme Judicial Council. Future dates are estimated according to the Umm al-Qura calendar of Saudi Arabia.[48] The Umm al-Qura is just a guide for planning purposes and not the absolute determinant or fixer of dates. Confirmations of actual dates by moon sighting are applied on the 29th day of the lunar month prior to Dhu al-Hijjah[49] to announce the specific dates for both Hajj rituals and the subsequent Eid festival. The three days after the listed date are also part of the festival. The time before the listed date the pilgrims visit Mount Ararat and descend from it after sunrise of the listed day.[50]

In many countries, the start of any lunar Hijri month varies based on the observation of new moon by local religious authorities, so the exact day of celebration varies by locality.

| Islamic year | Gregorian date |

|---|---|

| 1438 | 1 September 2017 |

| 1439 | 22 August 2018 |

| 1440 | 11 August 2019 |

| 1441 | 31 July 2020 |

| 1442 | 20 July 2021 (calculated) |

Notes

-

Allah is the greatest, Allah is the greatest,

There is no god but Allah

Allah is greatest, Allah is greatest

and to Allah goes all praise.[35]

References

- "First day of Hajj confirmed as Aug. 9". Arab News. 1 August 2019. Archived from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- Bentley, David (9 August 2019). "When is the Day of Arafah 2019 before the Eid al-Adha celebrations?". Birmingham Mail. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- "Islamic Holidays, 2010–2030 (A.H. 1431–1452)". InfoPlease. Archived from the original on 18 December 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "Id al-Adha - Oxford Islamic Studies Online". www.oxfordislamicstudies.com. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- Oxford Arabic Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2014. ISBN 978-0-19-958033-0.

- Badawi, Elsaid M.; Abdel Haleem, Muhammad (2008). Arabic–English Dictionary of Qur'anic Usage. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-14948-9.

- Jeffery, Arthur (2007). The Foreign Vocabulary of the Qur'ān. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-15352-3.

- Team, Almaany. "Translation and Meaning of ضحى In English, English Arabic Dictionary of terms Page 1". almaany.com. Archived from the original on 26 August 2019. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- (in Spanish) La Fiesta del Cordero en Marruecos Archived 25 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Ferdaous Emorotene, 25 November 2009

- Aksan, Yeşim; Aksan, Mustafa; Mersinli, Ümit; Demirhan, Umut Ufuk (2017). A Frequency Dictionary of Turkish. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-83965-6.

- Öztopçu, Kurtuluş; Abuov, Zhoumagaly; Kambarov, Nasir; Azemoun, Youssef (1996). Dictionary of the Turkic Languages. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-14198-2.

- Diouf, Niokhobaye, « Chronique du royaume du Sine », suivie de notes sur les traditions orales et les sources écrites concernant le royaume du Sine par Charles Becker et Victor Martin (1972). Bulletin de l'IFAN, tome 34, série B, no 4, 1972, pp. 706–07 (pp. 4–5), pp. 713–14 (pp. 9–10)

- « Cosaani Sénégambie » (« L’Histoire de la Sénégambie») : 1ere Partie relatée par Macoura Mboub du Sénégal. 2eme Partie relatée par Jebal Samba de la Gambie [in] programme de Radio Gambie: « Chosaani Senegambia ». Présentée par: Alhaji Mansour Njie. Directeur de programme: Alhaji Alieu Ebrima Cham Joof. Enregistré a la fin des années 1970, au début des années 1980 au studio de Radio Gambie, Bakau, en Gambie (2eme partie) et au Sénégal (1ere partie) [in] onegambia.com [in] The Seereer Resource Centre (SRC) (« le Centre de Resource Seereer ») : URL: http://www.seereer.com. Traduit et transcrit par The Seereer Resource Centre : Juillet 2014 p. 30 (retrieved: 25 September 2015)

- Brisebarre, Anne-Marie; Kuczynski, Liliane, « La Tabaski au Sénégal: une fête musulmane en milieu urbain », KARTHALA Editions (2009), pp. 86–87, ISBN 978-2811102449 Archived 13 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine (retrieved : 25 September 2015)

- Becker, Charles; Martin, Victor; Ndène, Aloyse, « Traditions villageoises du Siin », (Révision et édition par Charles Becker) (2014), p. 41

- Bianchi, Robert R. (2004). Guests of God: Pilgrimage and Politics in the Islamic World. Oxford University Press. p. 398. ISBN 978-0-19-029107-5. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- Ramzy, Sheikh (2012). The Complete Guide to Islamic Prayer (Salāh). ISBN 978-1477215302. Archived from the original on 1 July 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- Chanchreek, Jain; Chanchreek, K. L.; Jain, M. K. (2007). Encyclopaedia of Great Festivals. Shree Publishers & Distributors. p. 78. ISBN 978-8183291910.

- Kazim, Ebrahim (2010). Scientific Commentary of Suratul Faateḥah. Pharos Media & Publishing. p. 246. ISBN 978-81-7221-037-3. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- "Eid Al Adha (Sacrifice Feast of Muslims)". Prayer Times NYC. 8 August 2017. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- Noakes, Greg (April–May 1992). "Issues in Islam, All About Eid". Washington Report on Middle East Affairs. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- "Eid-el-Kabir All you need to know about Sallah – Pulse Nigeria". Archived from the original on 9 May 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- "Abraham". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 25 July 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- Bate, John Drew (1884). An Examination of the Claims of Ishmael as Viewed by Muḥammadans. BiblioBazaar. p. 2. ISBN 978-1117148366. Archived from the original on 6 February 2015. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

Ishmael sacrifice.

- Firestone, Reuven (1990). Journeys in Holy Lands: The Evolution of the -Ishmael Legends in Islamic Exegesis. SUNY Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0791403310.

- "The Significance of Hari Raya Aidiladha". muslim.sg. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- Elias, Jamal J. (1999). Islam. Routledge. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-415-21165-9. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- Muslim Information Service of Australia. "Eid al – Adha Festival of Sacrifice". Missionislam.com. Archived from the original on 8 December 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- Stephan Huller, Stephan (2011). The Real Messiah: The Throne of St. Mark and the True Origins of Christianity. Watkins; Reprint edition. ISBN 978-1907486647.

- Fasching, Darrell J.; deChant, Dell (2011). Comparative Religious Ethics: A Narrative Approach to Global Ethics. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1444331332.

- Quran 37:100–112 Abdullah Yusuf Ali translation

- Quran 5:114. "Said Jesus the son of Mary: ‘O Allah our Lord! Send us from heaven a table set (with viands), that there may be for us – for the first and the last of us – a solemn festival and a sign from thee; and provide for our sustenance, for thou art the best Sustainer (of our needs).’"

- "Should Muslims Sacrifice Animals on Eid-al-Adha?". The Wire. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- "Eid Al Adha 2020 (Bakrid) India: Date,Celebration,Quotes,Meaning,Origin". S A NEWS. 30 July 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- H. X. Lee, Jonathan (2015). Asian American Religious Cultures [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 357. ISBN 978-1598843309.

- Asmal, Fatima (6 July 2016). "South African women push for more inclusive Eid prayers". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 5 September 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- "Sunnah during Eid ul Adha according to Authentic Hadith". 13 November 2010. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2011 – via Scribd.

- حجم الحروف – Islamic Laws : Rules of Namaz » Adhan and Iqamah. Retrieved 10 August 2014

- "Eid ul-Fitr 2020: How to say Eid prayers". Hindustan Times. 23 May 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- "The Significance of Eid". Isna.net. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- McKernan, Bethan (29 August 2017). "Eid al-Adha 2017: When is it? Everything you need to know about the Muslim holiday". .independent. Archived from the original on 9 August 2019. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- "Eid Takbeers – Takbir of Id". Islamawareness.net. Archived from the original on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- Buğra Ekinci, Ekrem. "Qurban Bayram: How do Muslims celebrate a holy feast?". dailysabah. Archived from the original on 28 July 2018.

- Cussen, V.; Garces, L. (2008). Long Distance Transport and Welfare of Farm Animals. CABI. p. 35. ISBN 978-1845934033.

- "Bakra Eid: The cost of sacrifice". Asian Correspondent. 16 November 2010. Archived from the original on 28 December 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- Hewer, Chris (2006). Understanding Islam: The First Ten Steps. SCM Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-0334040323.

he Gregorian calendar.

- Staff, India com (30 July 2020). "Eid al-Adha or Bakrid 2020 Date And Time: History And Significance of The Day". India News, Breaking News, Entertainment News | India.com. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- "Eid al-Adha 2016 date is expected to be on September 11". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 14 August 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- "Mount Ararat | Location, Elevation, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 1 August 2020.