The Lord of the Rings

The Lord of the Rings is an epic[1] high-fantasy book by the English author and scholar J. R. R. Tolkien; he called it a "heroic romance", denying that it was a novel.[T 1] The story began as a sequel to Tolkien's 1937 children's book The Hobbit, but eventually developed into a much larger work. Written in stages between 1937 and 1949, The Lord of the Rings is one of the best-selling books ever written, with over 150 million copies sold.[2]

The first single-volume edition (1968) | |

| Author | J. R. R. Tolkien |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre |

|

| Publisher | Allen & Unwin |

| Published |

|

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| OCLC | 1487587 |

| Preceded by | The Hobbit |

| Followed by | The Adventures of Tom Bombadil |

The title names the story's main antagonist, the Dark Lord Sauron, who had in an earlier age created the One Ring to rule the other Rings of Power as the ultimate weapon in his campaign to conquer and rule all of Middle-earth. From homely beginnings in the Shire, a hobbit land reminiscent of the English countryside, the story ranges across Middle-earth, following the quest mainly through the eyes of the hobbits Frodo, Sam, Merry and Pippin.

Although generally known to readers as a trilogy, the work was initially intended by Tolkien to be one volume of a two-volume set, the other to be The Silmarillion, but this idea was dismissed by his publisher.[3][T 2] For economic reasons, The Lord of the Rings was published in three volumes over the course of a year from 29 July 1954 to 20 October 1955.[3][4] The three volumes were titled The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers and The Return of the King. Structurally, the work is divided internally into six books, two per volume, with several appendices of background material at the end. Some editions print the entire work into a single volume, following the author's original intent. The Lord of the Rings has since been reprinted many times and translated into at least 56 languages.

Tolkien's work, after an initially mixed reception by the literary establishment, has been the subject of extensive analysis of its themes and origins. Although a major work in itself, the story was only the last movement of a much older set of narratives Tolkien had worked on since 1917 encompassing The Silmarillion,[5] in a process he described as mythopoeia.[lower-alpha 1] Influences on this earlier work, and on the story of The Lord of the Rings, include philology, mythology, religion, earlier fantasy works, and his own experiences in the First World War. The Lord of the Rings in its turn has had a great effect on modern fantasy.

The enduring popularity of The Lord of the Rings has led to numerous references in popular culture, the founding of many societies by fans of Tolkien's works,[7] and the publication of many books about Tolkien and his works. It has inspired numerous derivative works including artwork, music, films and television, video games, board games, and subsequent literature. Award-winning adaptations of The Lord of the Rings have been made for radio, theatre, and film. It has been named Britain's best novel of all time in the BBC's The Big Read.

Plot summary

The Fellowship of the Ring

Prologue

The prologue explains that the book is "largely concerned with hobbits", and tells of their origins, migrating from the east; of how they smoke "pipe-weed"; of how the Shire where most of them live is organised; and how the narrative follows on from The Hobbit, in which the hobbit Bilbo Baggins finds the Ring, which had been in the possession of the creature Gollum.[T 3]

Book 1

Bilbo celebrates his 111th birthday and leaves the Shire, leaving the Ring to Frodo Baggins, his cousin[lower-alpha 2] and heir.[T 4] Neither hobbit is aware of the Ring's nature, but the suspicions of the wizard Gandalf the Grey are heightened. Seventeen years later, Gandalf tells Frodo that he has confirmed that the Ring is the one lost by the Dark Lord Sauron long ago and counsels him to take it away from the Shire.[T 5] Gandalf leaves, promising to return by Frodo's birthday and accompany him on his journey, but fails to do so. Frodo sets out on foot, ostensibly moving to his new home in Crickhollow, accompanied by his gardener, Sam Gamgee, and his cousin, Pippin Took. They are pursued by mysterious Black Riders. They meet a passing group of Elves and spend the night with them.[T 6] The next day they take a short cut to avoid the Riders, and arrive at the farm of Farmer Maggot. He takes them to Bucklebury Ferry, where they meet their friend Merry Brandybuck who was looking for them.[T 7] When they reach the house at Crickhollow, Merry and Pippin reveal they know about the Ring and insist on travelling with Frodo and Sam.[T 8] They decide to shake off the Black Riders by cutting through the Old Forest. Merry and Pippin are trapped by Old Man Willow, an evil tree who controls much of the forest, but are rescued by the mysterious Tom Bombadil.[T 9][T 10] Leaving, they are caught by a barrow-wight, who traps them in a barrow on the downs; Frodo, awakening, manages to call Bombadil, who frees them, and equips them with ancient swords from the barrow-wight's hoard.[T 11]

The hobbits reach the village of Bree, where they encounter a Ranger named Strider. The innkeeper gives Frodo a letter from Gandalf written three months before which identifies Strider as a friend.[T 12] Strider leads the hobbits into the wilderness after another close escape from the Black Riders, who they now know to be the Nazgûl, servants of Sauron.[T 13] On the hill of Weathertop, they are again attacked by the Nazgûl, who wound Frodo with a cursed blade.[T 14] Strider fights them off and leads the hobbits towards the Elven refuge of Rivendell. Frodo falls deathly ill from the wound. The Nazgûl nearly capture him at the Ford of Bruinen, but flood waters summoned by Elrond, master of Rivendell, rise up and overwhelm them.[T 15]

Book 2

Frodo recovers in Rivendell under Elrond's care.[T 16] The Council of Elrond discusses the history of Sauron and the Ring. Strider is revealed to be Aragorn, Isildur's heir. Gandalf reports that the chief wizard Saruman has betrayed them and is now working to become a power in his own right. Gandalf was captured by Saruman and had to escape, which is why he did not reach Frodo in time. The Council decides that the Ring must be destroyed, but that can only be done by sending it to the fire of Mount Doom in Mordor, where it was forged. Frodo takes this task upon himself.[T 17] Elrond, with the advice of Gandalf, chooses companions for him. The Fellowship of the Ring is nine in number: Frodo, Sam, Merry, Pippin, Aragorn, Gandalf, Gimli the Dwarf, Legolas the Elf, and the Man Boromir, son of Denethor, the Steward of Gondor.[T 18]

After a failed attempt to cross the Misty Mountains over the Redhorn Pass, the Company take the perilous path through the Mines of Moria. They learn that Balin and his colony of Dwarves were killed by Orcs.[T 19] After surviving an attack, they are pursued by Orcs and by a Balrog, an ancient fire demon. Gandalf faces the Balrog, and both of them fall into the abyss.[T 20] The others escape and find refuge in the Elven forest of Lothlórien,[T 21] where they are counselled by the Lady Galadriel. before they leave, Galadriel searches their hearts, and gives them individual, more or less magical, gifts to help them on their quest. She allows Frodo and Sam to look into her fountain, the Mirror of Galadriel, to see visions of past, present, and perhaps future.[T 22]

Celeborn gives the Fellowship boats, elven cloaks, and waybread, and the Company travel down the River Anduin to the hill of Amon Hen.[T 23][T 24] There, Boromir tries to take the Ring from Frodo, but Frodo puts it on and disappears. Frodo chooses to go alone to Mordor, but Sam guesses what he intends, intercepts him as he tries to take a boat across the river, and goes with him.[T 25]

The Two Towers

Book 3

Large Orcs, Uruk-hai, sent by Saruman and other Orcs sent by Sauron kill Boromir and capture Merry and Pippin.[T 26] Aragorn, Gimli and Legolas decide to pursue the Orcs taking Merry and Pippin to Saruman.[T 27] In the kingdom of Rohan, the Orcs are killed by Riders of Rohan, led by Éomer.[T 28] Merry and Pippin escape into Fangorn Forest, where they are befriended by Treebeard, the oldest of the tree-like Ents.[T 29] Aragorn, Gimli and Legolas track the hobbits to Fangorn. There they unexpectedly meet Gandalf.[T 30]

Gandalf explains that he killed the Balrog. Darkness took him, but he was sent back to Middle-earth to complete his mission. He is clothed in white and is now Gandalf the White, for he has taken Saruman's place as the chief of the wizards. Gandalf assures his friends that Merry and Pippin are safe.[T 30] Together they ride to Edoras, capital of Rohan. Gandalf frees Théoden, King of Rohan, from the influence of Saruman's spy Gríma Wormtongue. Théoden musters his fighting strength and rides with his men to the ancient fortress of Helm's Deep, while Gandalf departs to seek help from Treebeard.[T 31]

Meanwhile, the Ents, roused by Merry and Pippin from their peaceful ways, attack and destroy Isengard, Saruman's stronghold, and flood it, trapping the wizard in the tower of Orthanc.[T 32] Gandalf convinces Treebeard to send an army of Huorns to Théoden's aid. Gandalf brings an army of Rohirrim to Helm's Deep, and they defeat the Orcs, who flee into the forest of Huorns, never to be seen again.[T 33] Gandalf, Theoden, Legolas, and Gimli ride to Isengard, and are surprised to find Merry and Pippin relaxing amidst the ruins.[T 34] Gandalf offers Saruman a chance to turn away from evil. When Saruman refuses to listen, Gandalf strips him of his rank and most of his powers.[T 35] After Saruman crawls back to his prison, Wormtongue throws down a hard round object to try to kill Gandalf. Pippin picks it up. Gandalf takes it, but Pippin steals it in the night. It is revealed to be a palantír, a seeing-stone that Saruman used to speak with Sauron, and that Sauron used to ensnare him. Pippin is seen by Sauron. Gandalf rides for Minas Tirith, chief city of Gondor, taking Pippin with him.[T 36]

Book 4

Frodo and Sam struggle through the barren hills and cliffs of the Emyn Muil. They become aware they are being watched and tracked; on a moonlit night they capture Gollum, who has followed them from Moria. Frodo makes Gollum swear to serve him, as Ringbearer, and asks him to guide them to Mordor.[T 37] Gollum leads them across the Dead Marshes. Sam overhears Gollum debating with his alter ego, Sméagol, whether to break his promise and steal the Ring.[T 38] They find that the Black Gate of Mordor is too well guarded, so instead they travel south through the land of Ithilien to a secret way that Gollum knows.[T 39][T 40] On the way, they are captured by Faramir, brother of Boromir, and his rangers. He resists the temptation to seize the Ring.[T 41] Gollum – who is torn between his loyalty to Frodo and his desire for the Ring – leads the hobbits to the pass,[T 42][T 43] but betrays Frodo to the great spider Shelob in the tunnels of Cirith Ungol.[T 44] Gollum leads them into Shelob's lair. Frodo holds up the Phial of the light of Elbereth's star given to him by Galadriel. The light blinds Shelob, and she backs down. Frodo manages to cut through a giant web using Sting, and they advance. Shelob attacks from another tunnel, and Frodo falls to her sting.[T 45] With the help of the Phial of Galadriel and the sword Sting, Sam fights off and seriously wounds the monster. Believing Frodo to be dead, Sam takes the Ring to continue the quest alone. Orcs find Frodo; Sam overhears them and learns that Frodo is still alive.[T 46]

The Return of the King

Book 5

Sauron sends a great army against Gondor. Gandalf arrives at Minas Tirith to warn Denethor of the attack,[T 47] while Théoden musters the Rohirrim to ride to Gondor's aid.[T 48] Minas Tirith is besieged; the Lord of the Nazgûl uses a battering-ram and the power of his Ring to destroy the city's gates.[T 49] Denethor, deceived by Sauron, falls into despair. He burns himself alive on a pyre, nearly taking his son Faramir with him.[T 50] Aragorn, accompanied by Legolas, Gimli and the Rangers of the North, takes the Paths of the Dead to recruit the Dead Men of Dunharrow, who are bound by a curse which denies them rest until they fulfil their ancient oath to fight for the King of Gondor.[T 51]

Following Aragorn, the Army of the Dead strikes terror into the Corsairs of Umbar invading southern Gondor. Aragorn defeats the Corsairs and uses their ships to transport the men of southern Gondor up the Anduin,[T 52] reaching Minas Tirith just in time to turn the tide of battle.[T 53] Théoden's niece Éowyn, who joined the army in disguise,[T 48] kills the Lord of the Nazgûl with help from Merry; both are wounded. Together, Gondor and Rohan defeat Sauron's army in the Battle of the Pelennor Fields, though at great cost; King Théoden is among the dead.[T 54]

Aragorn leads an army of men from Gondor and Rohan, marching through Ithilien to the Black Gate to distract Sauron from his true danger.[T 52] His army for the Battle of the Morannon is vastly outnumbered by the great might of Mordor. Sauron attacks with overwhelming force.[T 55]

Book 6

Meanwhile, Sam rescues Frodo from the tower of Cirith Ungol.[T 56] They set out across Mordor.[T 57] Frodo and Sam reach the edge of the Cracks of Doom, but Frodo cannot resist the Ring any longer. He claims it for himself and puts it on his finger.[T 58] Gollum suddenly reappears. He struggles with Frodo and bites off Frodo's finger with the Ring still on it. Celebrating wildly, Gollum loses his footing and falls into the Fire, taking the Ring with him.[T 58] When the Ring is destroyed, Sauron loses his power forever. All he created collapses, the Nazgûl perish, and his armies are thrown into such disarray that Aragorn's forces emerge victorious.[T 59]

Aragorn is crowned King of Arnor and Gondor, and weds Arwen, daughter of Elrond.[T 60] Théoden is buried and Éomer is crowned King of Rohan. His sister Éowyn is engaged to marry Faramir, now Steward of Gondor and Prince of Ithilien. Galadriel, Celeborn, and Gandalf meet and say farewell to Treebeard, and to Aragorn.[T 61]

The four hobbits make their way back to the Shire,[T 62] only to find that it has been taken over by men directed by "Sharkey" (whom they later discover to be Saruman). The hobbits, led by Merry, raise a rebellion and scour the Shire of Sharkey's evil. Gríma Wormtongue turns on Saruman and kills him in front of Bag End, Frodo's home. He is killed in turn by hobbit archers.[T 63] Merry and Pippin are celebrated as heroes. Sam marries Rosie Cotton and uses his gifts from Galadriel to help heal the Shire. But Frodo is still wounded in body and spirit, having borne the Ring for so long. A few years later, in the company of Bilbo and Gandalf, Frodo sails from the Grey Havens west over the Sea to the Undying Lands to find peace.[T 64]

Appendices

The Tale of Aragorn and Arwen tells how it came about that an immortal elf came to marry a man, as Arwen's ancestor Lúthien had done in the First Age, giving up her immortality.[T 65] It is told, too, that Sam gives his daughter Elanor the Red Book of Westmarch, which contains the story of Bilbo's adventures and the War of the Ring as witnessed by the hobbits. It is said there was a tradition that Sam crossed west over the Sea himself, the last of the Ring-bearers; and that some years later, after the deaths of Aragorn and Arwen, that Legolas and Gimli too sailed "over Sea".[T 66]

Frame-story

Tolkien presents The Lord of the Rings within a fictional frame-story where he is not the original author, but merely the translator of part of an ancient document, the Red Book of Westmarch.[8] That book is modelled on the real Red Book of Hergest, which similarly presents an older mythology. Various details of the frame-story appear in the Prologue, its 'Note on Shire Records', and in the Appendices, notably Appendix F. In this frame-story, the Red Book is the source of Tolkien's other works relating to Middle-earth: The Hobbit, The Silmarillion, and The Adventures of Tom Bombadil.[9]

Concept and creation

Background

The Lord of the Rings started as a sequel to Tolkien's work The Hobbit, published in 1937.[10] The popularity of The Hobbit had led George Allen & Unwin, the publishers, to request a sequel. Tolkien warned them that he wrote quite slowly, and responded with several stories he had already developed. Having rejected his contemporary drafts for The Silmarillion, putting Roverandom on hold, and accepting Farmer Giles of Ham, Allen & Unwin continued to ask for more stories about hobbits.[11] So at the age of 45, Tolkien began writing the story that would become The Lord of the Rings.[12] The story was not finished until 12 years later, in 1949, and was not fully published until 1955, when Tolkien was 63 years old.[13]

Writing

Persuaded by his publishers, he started "a new Hobbit" in December 1937.[10] After several false starts, the story of the One Ring emerged. The idea for the first chapter ("A Long-Expected Party") arrived fully formed, although the reasons behind Bilbo's disappearance, the significance of the Ring, and the title The Lord of the Rings did not arrive until the spring of 1938.[10] Originally, he planned to write a story in which Bilbo had used up all his treasure and was looking for another adventure to gain more; however, he remembered the Ring and its powers and thought that would be a better focus for the new work.[10] As the story progressed, he brought in elements from The Silmarillion mythology.[14]

Writing was slow, because Tolkien had a full-time academic position teaching linguistics.[10] "I have spent nearly all the vacation-times of seventeen years examining [...] Writing stories in prose or verse has been stolen, often guiltily, from time already mortgaged..."[T 67] Tolkien abandoned The Lord of the Rings during most of 1943 and only restarted it in April 1944,[10] as a serial for his son Christopher Tolkien, who was sent chapters as they were written while he was serving in South Africa with the Royal Air Force. Tolkien made another major effort in 1946, and showed the manuscript to his publishers in 1947.[10] The story was effectively finished the next year, but Tolkien did not complete the revision of earlier parts of the work until 1949.[10] The original manuscripts, which total 9,250 pages, now reside in the J. R. R. Tolkien Collection at Marquette University.[15]

Poetry

Unusually for 20th century novels, the prose narrative is supplemented throughout by over 60 pieces of poetry. These include verse and songs of many genres: for wandering, marching to war, drinking, and having a bath; narrating ancient myths, riddles, prophecies, and magical incantations; of praise and lament (elegy). Some, such as riddles, charms, elegies, and narrating heroic actions are found in Old English poetry.[16] Scholars have stated that the poetry is essential for the fiction to work aesthetically and thematically; it adds information not given in the prose; and it brings out characters and their backgrounds.[17][18] The poetry has been judged to be of high technical skill, which Tolkien carried across into his prose, for instance writing much of Tom Bombadil's speech in metre.[19]

Influences

Tolkien drew on a wide array of influences including language,[21] Christianity,[T 68] mythology,[22] archaeology especially at the Temple of Nodens,[23] ancient and modern literature, and personal experience. He was inspired primarily by his profession, philology;[T 69] his work centred on the study of Old English literature, especially Beowulf, and he acknowledged its importance to his writings.[20] He was a gifted linguist, influenced by Celtic,[24][22] Finnish,[25] Slavic,[26] and Greek language and mythology.[27] Commentators have attempted to identify literary and topological antecedents for characters, places and events in Tolkien's writings; he acknowledged that he had enjoyed adventure stories by authors such as John Buchan and Rider Haggard.[28][29][30] Some writers were certainly important to him, including the Arts and Crafts polymath William Morris,[T 70] and he undoubtedly made use of some real place-names, such as Bag End, the name of his aunt's home.[31] Tolkien stated, too, that he had been influenced by his childhood experiences of the English countryside of Worcestershire near Sarehole Mill, and its urbanisation by the growth of Birmingham,[T 71] and his personal experience of fighting in the trenches of the First World War.[32]

Themes

Scholars and critics have identified many themes in the book, including a reversed quest,[33][34] the struggle of good and evil,[35] death and immortality,[36] fate and free will,[37] the danger of power,[38] and various aspects of Christianity such as the presence of three Christ figures, for prophet, priest, and king, as well as elements like hope and redemptive suffering.[39][40][41][42] There is a strong thread throughout the work of language, its sound, and its relationship to peoples and places, along with moralisation from descriptions of landscape.[43] Out of these, Tolkien stated that the central theme is death and immortality.[T 72] To those who supposed that the book was an allegory of events in the 20th century, Tolkien replied in the Foreword to the Second Edition that it was not, saying he preferred "history, true or feigned, with its varied applicability to the thought and experience of readers."[T 73]

Publication history

A dispute with his publisher, George Allen & Unwin, led to his offering the work to William Collins in 1950. Tolkien intended The Silmarillion (itself largely unrevised at this point) to be published along with The Lord of the Rings, but Allen & Unwin were unwilling to do this. After Milton Waldman, his contact at Collins, expressed the belief that The Lord of the Rings itself "urgently wanted cutting", Tolkien eventually demanded that they publish the book in 1952.[44] Collins did not; and so Tolkien wrote to Allen and Unwin, saying, "I would gladly consider the publication of any part of the stuff", fearing his work would never see the light of day.[10]

For publication, the work was divided into three volumes to minimize any potential financial loss due to the high cost of type-setting and modest anticipated sales: The Fellowship of the Ring (Books I and II), The Two Towers (Books III and IV), and The Return of the King (Books V and VI plus six appendices).[45] Delays in producing appendices, maps and especially an index led to the volumes being published later than originally hoped – on 29 July 1954, on 11 November 1954 and on 20 October 1955 respectively in the United Kingdom. In the United States, Houghton Mifflin published The Fellowship of the Ring on 21 October 1954, The Two Towers on 21 April 1955, and The Return of the King on 5 January 1956.[46]

The Return of the King was especially delayed as Tolkien revised the ending and preparing appendices (some of which had to be left out because of space constraints). Tolkien did not like the title The Return of the King, believing it gave away too much of the storyline, but deferred to his publisher's preference.[47] Tolkien wrote that the title The Two Towers "can be left ambiguous,"[T 74] but considered naming the two as Orthanc and Barad-dûr, Minas Tirith and Barad-dûr, or Orthanc and the Tower of Cirith Ungol.[T 75] However, a month later he wrote a note published at the end of The Fellowship of the Ring and later drew a cover illustration, both of which identified the pair as Minas Morgul and Orthanc.[48][49]

Tolkien was initially opposed to titles being given to each two-book volume, preferring instead the use of book titles: e.g. The Lord of the Rings: Vol. 1, The Ring Sets Out and The Ring Goes South; Vol. 2, The Treason of Isengard and The Ring Goes East; Vol. 3, The War of the Ring and The End of the Third Age. However these individual book titles were dropped, and after pressure from his publishers, Tolkien suggested the volume titles: Vol. 1, The Shadow Grows; Vol. 2, The Ring in the Shadow; Vol. 3, The War of the Ring or The Return of the King.[50][51]

Because the three-volume binding was so widely distributed, the work is often referred to as the Lord of the Rings "trilogy". In a letter to the poet W. H. Auden, who famously reviewed the final volume in 1956,[52], Tolkien himself made use of the term "trilogy" for the work[T 76] though he did at other times consider this incorrect, as it was written and conceived as a single book.[T 77] It is often called a novel; however, Tolkien objected to this term as he viewed it as a heroic romance.[T 1]

The books were published under a profit-sharing arrangement, whereby Tolkien would not receive an advance or royalties until the books had broken even, after which he would take a large share of the profits.[53] It has ultimately become one of the best-selling novels ever written, with 50 million copies sold by 2003[54] and over 150 million copies sold by 2007.[2] The work was published in the UK by Allen & Unwin until 1990, when the publisher and its assets were acquired by HarperCollins.[55][56]

Editions and revisions

In the early 1960s Donald A. Wollheim, science fiction editor of the paperback publisher Ace Books, claimed that The Lord of the Rings was not protected in the United States under American copyright law because Houghton Mifflin, the US hardcover publisher, had neglected to copyright the work in the United States.[57][58] Then, in 1965, Ace Books proceeded to publish an edition, unauthorized by Tolkien and without paying royalties to him. Tolkien took issue with this and quickly notified his fans of this objection.[59] Grass-roots pressure from these fans became so great that Ace Books withdrew their edition and made a nominal payment to Tolkien.[60][T 78]

Authorized editions followed from Ballantine Books and Houghton Mifflin to tremendous commercial success. Tolkien undertook various textual revisions to produce a version of the book that would be published with his consent and establish an unquestioned US copyright. This text became the Second Edition of The Lord of the Rings, published in 1965.[60] The first Ballantine paperback edition was printed in October that year, and sold a quarter of a million copies within ten months. On 4 September 1966, the novel debuted on The New York Times's Paperback Bestsellers list as number three, and was number one by 4 December, a position it held for eight weeks.[61] Houghton Mifflin editions after 1994 consolidate variant revisions by Tolkien, and corrections supervised by Christopher Tolkien, which resulted, after some initial glitches, in a computer-based unified text.[62]

In 2004, for the 50th Anniversary Edition, Wayne G. Hammond and Christina Scull, under supervision from Christopher Tolkien, studied and revised the text to eliminate as many errors and inconsistencies as possible, some of which had been introduced by well-meaning compositors of the first printing in 1954, and never been corrected.[63] The 2005 edition of the book contained further corrections noticed by the editors and submitted by readers. Yet more corrections were made in the 60th Anniversary Edition in 2014.[64] Several editions, including the 50th Anniversary Edition, print the whole work in one volume, with the result that pagination varies widely over the various editions.[65]

Posthumous publication of drafts

From 1988 to 1992 Christopher Tolkien published the surviving drafts of The Lord of The Rings, chronicling and illuminating with commentary the stages of the text's development, in volumes 6–9 of his History of Middle-earth series. The four volumes carry the titles The Return of the Shadow, The Treason of Isengard, The War of the Ring, and Sauron Defeated.[66]

Translations

The work has been translated, with varying degrees of success, into at least 56 languages.[67] Tolkien, an expert in philology, examined many of these translations, and made comments on each that reflect both the translation process and his work. As he was unhappy with some choices made by early translators, such as the Swedish translation by Åke Ohlmarks,[T 79] Tolkien wrote a "Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings" (1967). Because The Lord of the Rings purports to be a translation of the fictitious Red Book of Westmarch, with the English language representing the Westron of the "original", Tolkien suggested that translators attempt to capture the interplay between English and the invented nomenclature of the English work, and gave several examples along with general guidance.[68][69]

Reception

1950s

Early reviews for The Lord of the Rings were mixed. The initial review in the Sunday Telegraph described it as "among the greatest works of imaginative fiction of the twentieth century".[70] The Sunday Times echoed this sentiment, stating that "the English-speaking world is divided into those who have read The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit and those who are going to read them."[70] The New York Herald Tribune seemed to have an idea of how popular the books would become, writing in its review that they were "destined to outlast our time".[71] W. H. Auden, a former pupil of Tolkien's and an admirer of his writings, regarded The Lord of the Rings as a "masterpiece", further stating that in some cases it outdid the achievement of John Milton's Paradise Lost.[72] Kenneth F. Slater wrote in Nebula Science Fiction, April 1955, "... if you don't read it, you have missed one of the finest books of its type ever to appear".[73][74]

Even within Tolkien's literary group, The Inklings, Hugo Dyson complained loudly at its readings,[75][76] whereas C. S. Lewis had very different feelings, writing, "here are beauties which pierce like swords or burn like cold iron. Here is a book which will break your heart."[5] Lewis observed that the writing is rich in that some of the 'good' characters have darker sides, and likewise some of the villains have "good impulses".[77] Despite the mixed reviews and the lack of a paperback until the 1960s, The Lord of the Rings initially sold well in hardback.[5]

Later

Judith Shulevitz, writing in The New York Times, criticized the "pedantry" of Tolkien's literary style, saying that he "formulated a high-minded belief in the importance of his mission as a literary preservationist, which turns out to be death to literature itself".[78] The critic Richard Jenkyns, writing in The New Republic, criticized the work for a lack of psychological depth. Both the characters and the work itself were, according to Jenkyns, "anemic, and lacking in fibre".[79] The science fiction author David Brin interprets the work as holding unquestioning devotion to a traditional hierarchical social structure.[80] In his essay "Epic Pooh", fantasy author Michael Moorcock critiques the world-view displayed by the book as deeply conservative, in both the "paternalism" of the narrative voice and the power structures in the narrative.[81] Tom Shippey, like Tolkien an English philologist, notes the wide gulf between Tolkien's supporters, both popular and academic, and his literary detractors, and attempts to explain in detail both why the literary establishment disliked The Lord of the Rings, and the work's subtlety, themes, and merits.[82]

Awards

In 1957, The Lord of the Rings was awarded the International Fantasy Award. Despite its numerous detractors, the publication of the Ace Books and Ballantine paperbacks helped The Lord of the Rings become immensely popular in the United States in the 1960s. The book has remained so ever since, ranking as one of the most popular works of fiction of the twentieth century, judged by both sales and reader surveys.[83] In the 2003 "Big Read" survey conducted in Britain by the BBC, The Lord of the Rings was found to be the "Nation's best-loved book". In similar 2004 polls both Germany[84] and Australia[85] chose The Lord of the Rings as their favourite book. In a 1999 poll of Amazon.com customers, The Lord of the Rings was judged to be their favourite "book of the millennium".[86] In 2019, the BBC News listed The Lord of the Rings on its list of the 100 most influential novels.[87]

Adaptations

The Lord of the Rings has been adapted for film, radio and stage.

Radio

The book has been adapted for radio four times. In 1955 and 1956, the BBC broadcast The Lord of the Rings, a 13-part radio adaptation of the story. In the 1960s radio station WBAI produced a short radio adaptation. A 1979 dramatization of The Lord of the Rings was broadcast in the United States and subsequently issued on tape and CD. In 1981, the BBC broadcast The Lord of the Rings, a new dramatization in 26 half-hour instalments.[88]

Film

A variety of filmmakers considered adapting Tolkien's book, among them Stanley Kubrick, who thought it unfilmable,[89][90] Michaelangelo Antonioni, Heinz Edelmann,[91] and John Boorman.[92] Two film adaptations of the book have been made. The first was J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings (1978), by animator Ralph Bakshi, the first part of what was originally intended to be a two-part adaptation of the story; it covers The Fellowship of the Ring and part of The Two Towers.[93]

The second and more commercially successful adaptation was Peter Jackson's live action The Lord of the Rings film trilogy, produced by New Line Cinema and released in three instalments as The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001), The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (2002), and The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003). All three parts won multiple Academy Awards, including consecutive Best Picture nominations. The final instalment of this trilogy was the second film to break the one-billion-dollar barrier and won a total of 11 Oscars (something only two other films in history, Ben-Hur and Titanic, have accomplished), including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay.[94][95]

The Hunt for Gollum, a 2009 film by Chris Bouchard,[96][97] and the 2009 Born of Hope, written by Paula DiSante and directed by Kate Madison, are fan films based on details in the appendices of The Lord of the Rings.[98]

Television

Rankin and Bass used a loophole in the publication of The Lord of the Rings (which made it public domain in the US) to make an animated TV special based on the closing chapters of The Return of the King. It came out in 1980 to mixed reviews.[99][100]

In 2017, Amazon acquired the global television rights to The Lord of the Rings for a multi-season television series of new stories set before The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings,[101] based on J.R.R. Tolkien's writings about events of the Second Age of Middle-earth.[102] Amazon said the deal included potential for spin-off series as well.[103][104] The show will apparently be set in the early second age, during the time of the Forging of the Rings,[105] and will allegedly be a prequel to the live-action films.[106]

Stage

In 1990, Recorded Books published an audio version of The Lord of the Rings,[107] read by the British actor Rob Inglis. A large-scale musical theatre adaptation, The Lord of the Rings was first staged in Toronto, Ontario, Canada in 2006 and opened in London in June 2007; it was a commercial failure.[108]

Legacy

Influence on the fantasy genre

The enormous popularity of Tolkien's work expanded the demand for fantasy fiction. Largely thanks to The Lord of the Rings, the genre flowered throughout the 1960s, and enjoys popularity to the present day. The opus has spawned many imitators, such as The Sword of Shannara, which Lin Carter called "the single most cold-blooded, complete rip-off of another book that I have ever read".[109] Dungeons & Dragons, which popularized the role-playing game genre in the 1970s, features several races from The Lord of the Rings, including halflings (hobbits), elves, dwarves, half-elves, orcs, and dragons. However, Gary Gygax, lead designer of the game, maintained that he was influenced very little by The Lord of the Rings, stating that he included these elements as a marketing move to draw on the popularity the work enjoyed at the time he was developing the game.[110]

Because D&D has gone on to influence many popular role-playing video games, the influence of The Lord of the Rings extends to many of them as well, with titles such as Dragon Quest,[111][112] the Ultima series, EverQuest, the Warcraft series, and the Elder Scrolls series of games[113] as well as video games set in Middle-earth itself.

Music

In 1965, the songwriter Donald Swann, best known for his collaboration with Michael Flanders as Flanders & Swann, set six poems from The Lord of the Rings and one from The Adventures of Tom Bombadil ("Errantry") to music. When Swann met with Tolkien to play the songs for his approval, Tolkien suggested for "Namárië" (Galadriel's lament) a setting reminiscent of plain chant, which Swann accepted.[114] The songs were published in 1967 as The Road Goes Ever On: A Song Cycle,[115] and a recording of the songs performed by singer William Elvin with Swann on piano was issued that same year by Caedmon Records as Poems and Songs of Middle Earth.[116]

Rock bands of the 1970s were musically and lyrically inspired by the fantasy-embracing counter-culture of the time. The British rock band Led Zeppelin recorded several songs that contain explicit references to The Lord of the Rings, such as mentioning Gollum and Mordor in "Ramble On", the Misty Mountains in "Misty Mountain Hop", and Ringwraiths in "The Battle of Evermore". In 1970, the Swedish musician Bo Hansson released an instrumental concept album entitled Sagan om ringen ("The Saga of the Ring", the title of the Swedish translation at the time).[117] The album was subsequently released internationally as Music Inspired by Lord of the Rings in 1972.[117] From the 1980s onwards, many heavy metal acts have been influenced by Tolkien.[118]

In 1988, the Dutch composer and trombonist Johan de Meij completed his Symphony No. 1 "The Lord of the Rings". It had 5 movements, titled "Gandalf", "Lothlórien", "Gollum", "Journey in the Dark", and "Hobbits".[119]

Impact on popular culture

The Lord of the Rings has had a profound and wide-ranging impact on popular culture, beginning with its publication in the 1950s, but especially during the 1960s and 1970s, when young people embraced it as a countercultural saga.[120] "Frodo Lives!" and "Gandalf for President" were two phrases popular amongst United States Tolkien fans during this time.[121] Its impact is such that the words "Tolkienian" and "Tolkienesque" have entered the Oxford English Dictionary, and many of his fantasy terms, formerly little-known in English, such as "Orc" and "Warg", have become widespread in that domain.[122] Among its effects are numerous parodies, especially Harvard Lampoon's Bored of the Rings, which has had the distinction of remaining continuously in print from its publication in 1969, and of being translated into at least 11 languages.[123]

In 1969, Tolkien sold the merchandising rights to The Lord of The Rings (and The Hobbit) to United Artists under an agreement stipulating a lump sum payment of £10,000[124] plus a 7.5% royalty after costs,[125] payable to Allen & Unwin and the author.[126] In 1976, three years after the author's death, United Artists sold the rights to Saul Zaentz Company, who now trade as Tolkien Enterprises. Since then all "authorised" merchandise has been signed off by Tolkien Enterprises, although the intellectual property rights of the specific likenesses of characters and other imagery from various adaptations is generally held by the adaptors.[127]

Outside any commercial exploitation from adaptations, from the late 1960s onwards there has been an increasing variety of original licensed merchandise, from posters and calendars created by illustrators such as Barbara Remington.[128]

The work was named Britain's best novel of all time in the BBC's The Big Read.[129] In 2015, the BBC ranked The Lord of the Rings 26th on its list of the 100 greatest British novels.[130]

Notes

- Tolkien created the word to define a different view of myth from C. S. Lewis's "lies breathed through silver", writing the poem Mythopoeia to present his argument; it was first published in Tree and Leaf in 1988.[6]

- Although Frodo refers to Bilbo as his "uncle", the character is introduced in "A Long-expected Party" as one of Bilbo's younger cousins. The two were in fact first and second cousins, once removed either way (his paternal great-great-uncle's son's son and his maternal great-aunt's son).

References

Primary

- This list identifies each item's location in Tolkien's writings.

- Carpenter 1981, letter #329 to Peter Szabó Szentmihályi (draft), October 1971

- Carpenter 1981, letter #126 to Milton Waldman (draft), 10 March 1950

- The Fellowship of the Ring, "Prologue"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 1, ch. 1, "A Long-expected Party"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 1, ch. 2, "The Shadow of the Past"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 1, ch. 3, "Three is Company"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 1, ch. 4, "A Short Cut to Mushrooms"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 1, ch. 5, "A Conspiracy Unmasked"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 1, ch. 6, "The Old Forest"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 1, ch. 7, "In the House of Tom Bombadil"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 1, ch. 8, "Fog on the Barrow-downs"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 1, ch. 9, "At the Sign of the Prancing Pony"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 1, ch. 10, "Strider"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 1, ch. 11, "A Knife in the Dark"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 1, ch. 12, "Flight to the Ford"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 2, ch. 1, "Many Meetings"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 2, ch. 2, "The Council of Elrond"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 2, ch. 3, "The Ring Goes South"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 2, ch. 4, "A Journey in the Dark"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 2, ch. 5, "The Bridge of Khazad-Dum"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 2, ch. 6, "Lothlórien"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 2, ch. 7, "The Mirror of Galadriel"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 2, ch. 8, "Farewell to Lórien"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 2, ch. 9, "The Great River"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 2, ch. 10, "The Breaking of the Fellowship"

- The Two Towers, book 3, ch. 1 "The Departure of Boromir"

- The Two Towers, book 3, ch. 3 "The Uruk-hai"

- The Two Towers, book 3, ch. 2 "The Riders of Rohan"

- The Two Towers, book 3, ch. 4 "Treebeard"

- The Two Towers, book 3, ch. 5, "The White Rider"

- The Two Towers, book 3, ch. 6 "The King of the Golden Hall"

- The Two Towers, book 3, ch. 9 "Flotsam and Jetsam"

- The Two Towers, book 3, ch. 7 "Helm's Deep"

- The Two Towers, book 3, ch. 8 "The Road to Isengard"

- The Two Towers, book 3, ch. 10, "The Voice of Saruman"

- The Two Towers, book 3, ch. 11, "The Palantír"

- The Two Towers, book 4, ch. 1, "The Taming of Sméagol"

- The Two Towers, book 4, ch. 2, "The Passage of the Marshes"

- The Two Towers, book 4, ch. 3, "The Black Gate is Closed"

- The Two Towers, book 4, ch. 4, "Of Herbs and Stewed Rabbit"

- The Two Towers, book 4, ch. 5, "The Window on the West"

- The Two Towers, book 4, ch. 6, "The Forbidden Pool"

- The Two Towers, book 4, ch. 7, "Journey to the Cross-Roads"

- The Two Towers, book 4, ch. 8, "The Stairs of Cirith Ungol"

- The Two Towers, book 4, ch. 9, "Shelob's Lair"

- The Two Towers, book 4, ch. 10, "The Choices of Master Samwise"

- The Return of the King, book 5, ch. 1 "Minas Tirith"

- The Return of the King, book 5, ch. 3 "The Muster of Rohan"

- The Return of the King, book 5, ch. 4 "The Siege of Gondor"

- The Return of the King, book 5, ch. 7 "The Pyre of Denethor"

- The Return of the King, book 5, ch. 2 "The Passing of the Grey Company"

- The Return of the King, book 5, ch. 9 "The Last Debate".

- The Return of the King, book 5, ch. 5 "The Ride of the Rohirrim"

- The Return of the King, book 5, ch. 6 "The Battle of the Pelennor Fields"

- The Return of the King, book 5, ch. 10 "The Black Gate Opens"

- The Return of the King, book 6, ch. 1, "The Tower of Cirith Ungol"

- The Return of the King, book 6, ch. 2, "The Land of Shadow"

- The Return of the King, book 6, ch. 3, "Mount Doom"

- The Return of the King, book 6, ch. 4 "The Field of Cormallen"

- The Return of the King, book 6, ch. 5 "The Steward and the King"

- The Return of the King, book 6, ch. 6, "Many Partings"

- The Return of the King, book 6, ch. 7, "Homeward Bound"

- The Return of the King, book 6, ch. 8, "The Scouring of the Shire"

- The Return of the King, book 6, ch. 9, "The Grey Havens"

- The Return of the King, Appendix A: "Annals of the Kings and Rulers": 1 "The Númenórean Kings" (v) "Here follows a part of the Tale of Aragorn and Arwen"

- The Return of the King Appendix B "The Tale of Years", "Later events concerning the members of the fellowship of the Ring"

- Carpenter 1981, letter #17 to Stanley Unwin, 15 October 1937

- Carpenter 1981, letter #142 to Robert Murray, S. J., 2 December 1953

- Carpenter 1981, letter #165 to Houghton Mifflin, 30 June 1955

- Carpenter 1981, letter #19 to Stanley Unwin, 31 December 1960

- Carpenter 1981, letter #178 to Allen & Unwin, 12 December 1955, and #303 to Nicholas Thomas, 6 May 1968

- Carpenter 1981, letter #211 to Rhona Beare, 14 October 1958

- The Fellowship of the Ring, "Foreword to the Second Edition"

- Carpenter 1981, letter #140 to Rayner Unwin, 17 August 1953

- Carpenter 1981, letter #143 to Rayner Unwin, 22 January 1954

- Carpenter 1981, letter #163 to W. H. Auden, 7 June 1955

- Carpenter 1981, letter #149 to Rayner Unwin, 9 September 1954

- Carpenter 1981, letters #270, #273 and #277

- Carpenter 1981, letters #228 and #229 to Allen & Unwin, 24 January 1961 and 23 February 1961

Secondary

- Chance, Jane (1980) [1979]. The Lord of the Rings: Tolkien's Epic. Tolkien's Art: A Mythology for England. Macmillan. pp. 97–127. ISBN 0333290348.

- Wagner, Vit (16 April 2007). "Tolkien proves he's still the king". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 9 March 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- Reynolds, Pat. "The Lord of the Rings: The Tale of a Text" (PDF). The Tolkien Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- "The Life and Works for JRR Tolkien". BBC. 7 February 2002. Archived from the original on 1 November 2010. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- Doughan, David. "J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biographical Sketch". TolkienSociety.org. Archived from the original on 3 March 2006. Retrieved 16 June 2006.

- Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina (2006). The J.R.R. Tolkien Companion and Guide: II. Reader's Guide. pp. 620–622. ISBN 978-0008214531.

- Gilsdorf, Ethan (23 March 2007). "Elvish Impersonators". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 December 2007. Retrieved 3 April 2007.

- Hooker, Mark T. (2006). The Feigned-manuscript Topos. A Tolkienian Mathomium: a collection of articles on J. R. R. Tolkien and his legendarium. Llyfrawr. p. 176-177. ISBN 978-1-4382-4631-4.

- Bowman, Mary R. (October 2006). "The Story Was Already Written: Narrative Theory in "The Lord of the Rings"". Narrative. 14 (3): 272–293. doi:10.1353/nar.2006.0010. JSTOR 20107391.

the frame of the Red Book of Westmarch, which becomes one of the major structural devices Tolkien uses to invite meta-fictional reflection... He claims, in essence, that the story was already written...

- Carpenter 1977, pp. 187-208

- Carpenter 1977, p. 195.

- Carpenter 1977, pp. 187-190.

- Carpenter 1977, pp. 222-225.

- Rérolle, Raphaëlle (5 December 2012). "My Father's 'Eviscerated' Work – Son Of Hobbit Scribe J.R.R. Tolkien Finally Speaks Out". Le Monde/Worldcrunch. Archived from the original on 10 February 2013.

- "J. R. R. Tolkien Collection | Marquette Archives | Raynor Memorial Libraries | Marquette University". Archived from the original on 19 December 2013.

- Kullmann, Thomas (2013). "Poetic Insertions in Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings". Connotations: A Journal for Critical Debate. 23 (2): 283–309. Archived from the original on 8 November 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- Higgins, Andrew (2014). "Tolkien's Poetry (2013), edited by Julian Eilmann and Allan Turner". Journal of Tolkien Research. 1 (1). Article 4. Archived from the original on 1 August 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- Straubhaar, Sandra Ballif (2005). "Gilraen's Linnod : Function, Genre, Prototypes". Journal of Tolkien Studies. 2 (1): 235–244. doi:10.1353/tks.2005.0032. ISSN 1547-3163.

- Zimmer, Paul Edwin (1993). "Another Opinion of 'The Verse of J.R.R. Tolkien'". Mythlore. 19 (2). Article 2.

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). HarperCollins. pp. 74, 169-170 and passim. ISBN 978-0261102750.

- Readanybooks website; English and Welsh essay Archived 3 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine; access-date 25 January 2014

- Lee, Stuart D.; Solopova, Elizabeth (2005). The Keys of Middle-earth: Discovering Medieval Literature Through the Fiction of J. R. R. Tolkien. Palgrave. pp. 124–125. ISBN 978-1403946713.

- Anger, Don N. (2013) [2007]. "Report on the Excavation of the Prehistoric, Roman and Post-Roman Site in Lydney Park, Gloucestershire". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. pp. 563–564. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- Burns, Marjorie (2005). Perilous Realms: Celtic and Norse in Tolkien's Middle-earth. University of Toronto Press. pp. 13–29 and passim. ISBN 978-0-8020-3806-7.

- Handwerk, Brian (1 March 2004). "Lord of the Rings Inspired by an Ancient Epic". National Geographic News. National Geographic Society. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original on 16 March 2006. Retrieved 4 October 2006.

- Kuzmenko, Dmitry. "Slavic echoes in the works of J.R.R. Tolkien" (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- Stanton, Michael (2001). Hobbits, Elves, and Wizards: Exploring the Wonders and Worlds of J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 18. ISBN 1-4039-6025-9.

- Resnick, Henry (1967). "An Interview with Tolkien". Niekas: 37–47.

- Nelson, Dale (2013) [2007]. "Literary Influences, Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. pp. 366–377. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- Hooker, Mark T. (2011). Fisher, Jason (ed.). Reading John Buchan in Search of Tolkien. Tolkien and the study of his sources : critical essays. McFarland. pp. 162–192. ISBN 978-0-7864-6482-1. OCLC 731009810.

- "Lord of the Rings inspiration in the archives". Explore the Past (Worcestershire Historic Environment Record). 29 May 2013.

- Livingston, Michael (2006). "The Shellshocked Hobbit: The First World War and Tolkien's Trauma of the Ring". Mythlore. Mythopoeic Society. pp. 77–92. Archived from the original on 23 December 2011. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- Campbell, Lori M. (2010). Portals of Power: Magical Agency and Transformation in Literary Fantasy. McFarland. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-7864-5655-0.

- West, Richard C. (1975). Lobdell, Jared (ed.). Narrative Pattern in 'The Fellowship of the Ring'. A Tolkien Compass. Open Court. p. 96. ISBN 978-0875483030.

- Flieger, Verlyn (2002). Splintered Light: Logos and Language in Tolkien's World (2nd ed.). Kent State University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-87338-744-6.

- Hannon, Patrice (2004). "The Lord of the Rings as Elegy". Mythlore. 24 (2): 36–42.

- Isaacs, Neil David; Zimbardo, Rose A. (2005). Understanding The Lord of the Rings: The Best of Tolkien Criticism. Houghton Mifflin. pp. 58–64. ISBN 978-0-618-42253-1.

- Perkins, Agnes; Hill, Helen (1975). Lobdell, Jared (ed.). The Corruption of Power. A Tolkien Compass. Open Court. pp. 57–68. ISBN 978-0875483030.

- Kreeft, Peter J. (November 2005). "The Presence of Christ in The Lord of the Rings". Ignatius Insight.

- Kerry, Paul E. (2010). Kerry, Paul E. (ed.). The Ring and the Cross: Christianity and the Lord of the Rings. Fairleigh Dickinson. pp. 32–34. ISBN 978-1-61147-065-9.

- Schultz, Forrest W. (1 December 2002). "Christian Typologies in The Lord of the Rings". Chalcedon. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- Williams, Stan. "20 Ways 'The Lord of the Rings' Is Both Christian and Catholic". Catholic Education Resource Center. Archived from the original on 20 December 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). HarperCollins. pp. 129–133, 245–246. ISBN 978-0261102750.

- Carpenter 1977, pp. 211 ff..

- Unwin, Rayner (1999). George Allen & Unwin: A Remembrancer. Merlin Unwin Books. pp. 97–99. ISBN 1-873674-37-6.

- The Fellowship of the Ring: Being the First Part of The Lord of the Rings] (publication history) Archived 15 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- "From Book to Script", The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring Appendices (DVD). New Line Cinema. 2002.

- "The second part is called The Two Towers, since the events recounted in it are dominated by Orthanc, ..., and the fortress of Minas Morgul..."

- "Tolkien's own cover design for The Two Towers". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- Carpenter 1981, letter #137, #140, #143 all to Rayner Unwin, his publisher, in 1953-4

- Tolkien, Christopher (2000). The War of the Ring: The History of The Lord of the Rings. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-08359-6.

- Auden, W. H. (26 January 1956). "At the End of the Quest, Victory: Book Review, "The Return of the King"". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- Sturgis, Amy H. (2013) [2007]. "Publication History". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 385–390. ISBN 978-0415865111.

- Pate, Nancy (20 August 2003). "Lord of the Rings Films Work Magic on Tolkien Book Sales". SunSentinel. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- Smith, Anthony (27 November 2000). "Rayner Unwin". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 May 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- Unwin, Rayner (1999). George Allen & Unwin: A Remembrancer. Merlin Unwin Books. p. 288. ISBN 1-873674-37-6.

- "Betsy Wollheim: The Family Trade". Locus Online. June 2006. Archived from the original on 31 January 2011. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- Silverberg, Robert (1997). Reflections & Refractions: Thoughts on Science Fiction, Science, and Other Matters. Underwood. pp. 253–256]. ISBN 1-887424-22-9.

- Ripp, Joseph. "Middle America Meets Middle-earth: American Publication and Discussion of J. R. R. Tolkien's Lord of the Rings" (PDF). p. 38. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 November 2015.

- Reynolds, Pat. "The Lord of the Rings: The Tale of a Text". The Tolkien Society. Archived from the original on 8 September 2006.

- Medievalist Comics and the American Century Archived 15 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- "Notes on the text" pp. xi–xiii, Douglas A. Anderson, in the 1994 HarperCollins edition of The Fellowship of the Ring.

- Hammond & Scull 2005, pp. xl–xliv.

- "Lord of the Rings Comparison". Archived from the original on 7 October 2017.

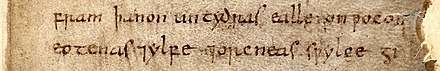

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (2004). The Lord of the Rings 50th Anniversary Edition. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-261-10320-7.

This special 50th anniversary hardback edition of J.R.R. Tolkien's classic masterpiece includes the complete revised and reset text, two-fold out maps printed in red and black and, unique to this edition, a full-colour fold-out reproduction of Tolkien's own facsimile pages from the Book of Mazarbul that the Fellowship discover in Moria.

- Tolkien, Christopher (2002) [1988-1992]. The History of the Lord of the Rings: Box Set (The History of Middle-Earth). HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-261-10370-2. OCLC 43216229.

- "Elrond's Library - Translations of Tolkien all over the world". www.elrondslibrary.fr. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- Lobdell, Jared (1975). Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings. A Tolkien Compass. Open Court. pp. 153–201. ISBN 978-0875483030.

- Hammond & Scull 2005, pp. 750-782.

- "The Lord of the Rings Boxed Set (Lord of the Rings Trilogy Series) section: Editorial reviews". Archived from the original on 10 December 2010. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- "From the Critics". Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 30 May 2006.

- Auden, W. H. (22 January 1956). "At the End of the Quest, Victory". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 February 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- "Ken Slater". Archived from the original on 30 October 2019. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- "Something to Read NSF 12". Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- Derek Bailey (Director) and Judi Dench (Narrator) (1992). A Film Portrait of J. R. R. Tolkien (Television documentary). Visual Corporation.

- Dyson's actual comment, bowdlerized in the TV version, was "Not another fucking Elf!" Grovier, Kelly (29 April 2007). "In the Name of the Father". The Observer. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- C. S. Lewis, quoted in Christina Scull & Wayne Hammond (2006), The J. R. R. Tolkien Companion and Guide, HarperCollins, article 'The Lord of the Rings', § Reviews, p. 549; ISBN 978-0-618-39113-4

- Shulevitz, Judith (22 April 2001). "Hobbits in Hollywood". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 April 2009. Retrieved 13 May 2006.

- Jenkyns, Richard (28 January 2002). "Bored of the Rings". The New Republic. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- Brin, David (December 2002). "We Hobbits are a Merry Folk: an incautious and heretical re-appraisal of J.R.R. Tolkien". Salon Magazine. Archived from the original on 23 March 2006. Retrieved 9 January 2006.

- Moorcock, Michael. "Epic Pooh". Archived from the original on 24 March 2008. Retrieved 27 January 2006.

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). HarperCollins. pp. 1–6, and passim. ISBN 978-0261102750.

- Seiler, Andy (16 December 2003). "'Rings' comes full circle". USA Today. Archived from the original on 12 February 2006. Retrieved 12 March 2006.

- Diver, Krysia (5 October 2004). "A lord for Germany". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 28 March 2006. Retrieved 12 March 2006.

- Cooper, Callista (5 December 2005). "Epic trilogy tops favourite film poll". ABC News Online. Archived from the original on 16 January 2006. Retrieved 12 March 2006.

- O'Hehir, Andrew (4 June 2001). "The book of the century". Salon. Archived from the original on 13 February 2006. Retrieved 12 March 2006.

- "100 'most inspiring' novels revealed by BBC Arts". BBC News. 5 November 2019. Archived from the original on 8 November 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

The reveal kickstarts the BBC's year-long celebration of literature.

- "Riel Radio Theatre — The Lord of the Rings, Episode 2". Radioriel. 15 January 2009. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- Drout 2006, p. 15

- See also interview in "Show" magazine vol. 1, Number 1 1970

- "Beatles plan for Rings film". CNN. 28 March 2002. Archived from the original on 9 April 2002.

- Taylor, Patrick (19 January 2014). Best Films Never Made #8: John Boorman's The Lord of the Rings." Archived 16 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine OneRoomWithaView.com. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- Gaslin, Glenn (21 November 2001). "Ralph Bakshi's unfairly maligned Lord of the Rings". Slate.

- Rosenberg, Adam (14 January 2016). "'Star Wars' ties 'Lord of the Rings' with 30 Oscar nominations, the most for any series". Mashable. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- The Return of the King peak positions

- U.S. and Canada: "All Time Domestic Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 4 June 2004.

- Worldwide: "All Time Worldwide Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 5 June 2004.

- Masters, Tim (30 April 2009). "Making Middle-earth on a shoestring". BBC News. BBC. Archived from the original on 3 May 2009. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- Sydell, Laura (30 April 2009). "High-Def 'Hunt For Gollum' New Lord of the Fanvids". All Things Considered. NPR. Archived from the original on 3 May 2009. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- Lamont, Tom (7 March 2010). "Born of Hope – and a lot of charity". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 January 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- Cassady, Charles. "The Return of the King (1980)". commonsensemedia.org. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- Greydanus, Stephen. "The Return of the King (1980)". decentfilms.com. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- Axon, Samuel (13 November 2017). "Amazon will run a multi-season Lord of the Rings prequel TV series". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 14 November 2017.

- "Welcome to the Second Age:https://amazon.com/lotronprime". @LOTRonPrime. 7 March 2019. Archived from the original on 10 February 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- Gonzalez, Sandra (13 November 2017). "Amazon announces 'Lord of the Rings' TV show". CNN. Archived from the original on 14 November 2017.

- Koblin, John (13 November 2017). "'Lord of the Rings' Series Coming to Amazon". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 February 2018. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- "Amazon's Lord of the Rings Series Will Be Set in the Second Age". Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- "Narnia Fans: John Howe interview". Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- Inglis, Rob (narrator) (1990). The Lord of the Rings. Recorded Books. ISBN 1-4025-1627-4.

- "The fastest West End flops – in pictures". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- Carter, Lin (1978). The Year's Best Fantasy Stories: 4. DAW Books. pp. 207–208.

- Gygax, Gary. "Gary Gygax – Creator of Dungeons & Dragons". The One Ring.net. Archived from the original on 27 June 2006. Retrieved 28 May 2006.

- "The Gamasutra Quantum Leap Awards: Role-Playing Games". Honorable Mention: Dragon Warrior. Gamasutra. 6 October 2006. Archived from the original on 13 March 2011. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- Kalata, Kurt. "The History of Dragon Quest". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on 22 July 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2009.

- Douglass, Perry (17 May 2006). "The Influence of Literature and Myth in Videogames". IGN. News Corp. Archived from the original on 18 January 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- Tolkien had recorded a version of his theme on a friend's tape recorder in 1952. This was later issued by Caedmon Records in 1975 as part of J.R.R. Tolkien reads and sings The Lord of the Rings (LP recording TC1478).

- Tolkien, J.R.R.; Swann, Donald (1967). The Road Goes Ever On: A Song Cycle. Ballantine Books.

- Tolkien, J.R.R.; Swann, Donald (1967), Poems and Songs of Middle Earth (LP recording), Caedmon Records, TC1231/TC91231

- Snider, Charles (2008). The Strawberry Bricks Guide to Progressive Rock. Strawberry Bricks. pp. 120–121. ISBN 978-0-615-17566-9.

- Greene, Andy (16 August 2017). "Ramble On: Rockers Who Love 'The Lord of the Rings'". Rolling Stone. Wenner Media. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017.

- "The Lord of the Rings Der Herr der Ringe Symphony No. 1 Sinfonie Nr. 1". Rundel. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- Feist, Raymond (2001). Meditations on Middle-earth. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-30290-8.

- Carpenter, Humphrey (2000). J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biography. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 0-618-05702-1.

- Gilliver, Peter (2006). The Ring of Words: Tolkien and the Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. pp. 174, 201–206. ISBN 0-19-861069-6.

- Bratman, David (2013) [2007]. "Parodies". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. pp. 503–504. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- "Tolkien sold film rights for £10,000". London Evening Standard. 12 July 2001. Archived from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- Pulley, Brett (15 July 2009). "'Hobbit' Heirs Seek $220 Million for 'Rings' Rights (Update1)". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 2 August 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- Harlow, John (28 May 2008). "Hobbit movies meet dire foe in son of Tolkien". The Times Online. The Times. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

- Mathijs, Ernest (2006). The Lord of the Rings: Popular Culture in Global Context. Wallflower Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-904764-82-3.

- Carmel, Julia (15 February 2020). ""Barbara Remington, Illustrator of Tolkien Book Covers, Dies at 90"". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- Ezard, John (15 December 2003). "Tolkien runs rings round Big Read rivals". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- Ciabattari, Jane (7 December 2015). "The 100 greatest British novels". BBC. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

Further reading

- Carpenter, Humphrey (1977), Tolkien: A Biography, New York: Ballantine Books, ISBN 0-04-928037-6

- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (1981), The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-31555-7

- Drout, Michael D. C. (2006). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-96942-0.

- Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina (2005). The Lord of the Rings: A Reader's Companion. Houghton Mifflin Co. ISBN 978-0-00-720907-1.

- Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The History of The Lord of the Rings, 4 vols (1988–1992).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Lord of the Rings. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Lord of the Rings |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for The Lord of the Rings tourism. |

- Tolkien website of Harper Collins (the British publisher)

- Tolkien website of Houghton Mifflin (the American publisher)

- Lord of the Rings, The at the Encyclopedia of Fantasy

.jpg)