Tolkien: A Cultural Phenomenon

Tolkien: A Cultural Phenomenon is a 2003 book of literary criticism by Brian Rosebury about the English author and philologist J. R. R. Tolkien and his writings on his fictional world of Middle-earth, especially The Lord of the Rings. A shorter version of the book, Tolkien: A Critical Assessment, appeared in 1992.

Context

J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy writings about Middle-earth, especially The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, have become extremely popular,[1] and have exerted considerable influence since their publication,[2] but acceptance by the establishment of literary criticism has been slower. Nevertheless, academic studies on Tolkien's works have been appearing at an increasing pace since the mid-1980s, prompting a measure of literary re-evaluation of his work.[3]

Brian Rosebury is a lecturer in the humanities at the University of Central Lancashire. He has specialised in Tolkien, in literary aesthetics, and later in moral and political philosophy.[4]

Book

Publication history

A short version of the book (167 pages, four chapters, paperback) was first published by Macmillan in 1992 under the title Tolkien: A Critical Assessment.[5]

The full version of the book (246 pages, six chapters, paperback) was published by Palgrave Macmillan in 2003 under the title Tolkien: A Cultural Phenomenon.[5][6]

Synopsis

The book begins by examining how Tolkien imagined Middle-earth in The Lord of the Rings, and how he achieved the aesthetic effect he was seeking.[7] He then explores Tolkien's long career writing both prose and poetry, from the start of war in 1914 to his death in 1973.[8] The fourth chapter briefly situates Tolkien in the twentieth century literary scene, contrasting his work with Modernism and describing it as not ignorant of that movement but actually antagonistic to it.[9]

The later edition added two new chapters to the book. The first looks at Tolkien as a thinker within the history of ideas: it examines in turn how his writing relates to the times in which he lived, how his work has been used to support various ideologies, and the underlying coherence of his thinking.[10] The other chapter, which gives its title to the book, looks at the "afterlife" of his work, and how it has variously been retold in film and other media, assimilated to various genres, imitated by "thousands" of other authors, and, despite Tolkien's stated opinion that The Lord of the Rings was "quite unsuitable for 'dramatization'", adapted, most notably for film by Peter Jackson.[11]

Reception

Jane Chance, a Tolkien scholar, writes that the refusal by some critics to accept that Tolkien is a major writer has "consistently annoyed Tolkien readers ...over the past twenty-five years", but that Tom Shippey and Rosebury have attempted "to persuade these nay-sayers". She notes that Rosebury strategically uses Shippey to begin his book, praising him but saying that he doesn't clinch the argument that Tolkien's works are "of high quality". Rosebury then, she writes, applies his expertise as seen in his 1988 book Art and Desire: A Study in the Aesthetics of Fiction, to demonstrate Tolkien's aesthetic skill. She contrasts Shippey's comparison of Tolkien with fantasy authors from Orwell and Golding to T. H. White and C. S. Lewis, with Rosebury's search for parallels among the Modernists such as Proust, Joyce, and Eliot.[5] Claire Buck however comments in the J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia that this brings up the problematic definition of what "modern" is according to the same critics who thought Tolkien "a peripheral figure".[13]

Nancy-Lou Patterson, reviewing the first version of the book in Mythlore, notes that Tolkien criticism had been distinctly "uneven" at best, but British critics such as Rosebury were improving the standard. She liked his characterisation of "Tolkien's descriptive gifts as possessing 'a certain sensuous precision, distinctive of Tolkien'". She agreed with Rosebury's assertion that The Lord of the Rings works not because of its basis in Christianity but for its emotional appeal of a powerfully imagined but essentially good world that treats evil as the absence of good. In her view, Rosebury successfully defends The Lord of the Rings, even if she wouldn't call The Hobbit a minor work.[14]

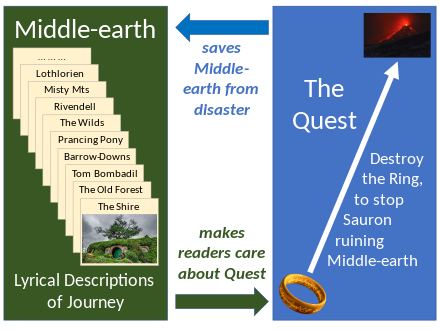

Liz Milner, in The Green Man Review, notes that the second version of the book makes use of two major developments: Christopher Tolkien's publication of his father's many Middle-earth manuscripts, and Peter Jackson's film version. She comments that the "refutation of Germaine Greer, Edmund Wilson and their cronies may have been needed in 1992",[12] but not any more. She found Rosebury at his best on Tolkien's literary techniques, especially his creation of Middle-earth in such convincing form, and his argument that The Lord of the Rings succeeds as a work of art because it connects readers' desire for Middle-earth with their desire for Frodo to fulfil his errand. She is fascinated, too, by Rosebury's discussion of the divergences of Tolkien's mythology from Christian doctrine, comparing Eru Iluvatar with Milton's God in Paradise Lost. She suggests that "general readers" will be most interested in the last chapter on the book's "afterlife" in film, games, and other artefacts. She notes that Rosebury calls Jackson's film trilogy a "qualified success" (based on the first two films); he admires the film realisation of Middle-earth, but mourns the loss of "some of the book's greatest virtues" including English understatement, emotional tact, and spaciousness, and the film version's choice of physical conflict over rhetorical power, "dignity of presence[,] or force of intellect", and the book's emphasis on free will and individual responsibility. She finds Rosebury less readable than Shippey, but it comes a close second with "some wonderful insights".[12]

Tom Shippey calls the book a compelling analysis, and finds Rosebury's explanation of how Tolkien wove free will, moral choice, and creativity into Middle-earth "especially convincing". He admired the account of Tolkien's narrative and descriptive skill, and thought Rosebury's chapter on Peter Jackson's film adaptation the "best available" at that time.[15]

Christopher Garbowski, in the J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia, writes that Rosebury looks at the humanistic implications of eucatastrophe, quoting him as saying that "the reader must be delighted in Middle-earth in order to care that Sauron does not lay it desolate".[16][17] The eucatastrophe is convincing because "its optimism is emotionally consonant with the work's pervasive sense of a universe hospitable to the humane."[16][18] Allan Turner comments in the same work that Rosebury rejects the unsupported assertions of archaising and "wrenched syntax" by critics like Catharine Stimpson, and that Rosebury pointed out that Tolkien used a plain descriptive style, demonstrably favouring the "familiar phrasal verbs 'have on' and 'get off' .. to the slightly more literary 'wear' and 'dismount'".[19]

See also

References

- Seiler, Andy (16 December 2003). "'Rings' comes full circle". USA Today. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- Mitchell, Christopher (12 April 2003). "J. R. R. Tolkien: Father of Modern Fantasy Literature" (streaming video). The Veritas Forum. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- Lobdell 2013.

- "Dr. Brian Rosebury, Senior Lecturer". University of Central Lancashire. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Chance 2005.

- Rosebury 2003, p. 246.

- Rosebury 2003, chapters 1, 2.

- Rosebury 2003, chapter 3.

- Rosebury 2003, chapter 4.

- Rosebury 2003, chapter 5.

- Rosebury 2003, chapter 6.

- Milner 2003.

- Buck 2013.

- Patterson 1997.

- "Reviews". Palgrave. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- Garbowski 2013.

- Rosebury 2003, p. 41.

- Rosebury 2003, p. 71.

- Turner 2013.

Sources

- Buck, Claire (2013) [2007]. "Literary Context, Twentieth Century". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 363–366. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- Chance, Jane (2005). "Tolkien: A Cultural Phenomenon (review)". Tolkien Studies. 2 (1): 262–265. doi:10.1353/tks.2005.0010. ISSN 1547-3163.

- Garbowski, Christopher (2013) [2007]. "Eucatastrophe". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 176–177. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- Lobdell, Jared (2013) [2007]. "Criticism of Tolkien, Twentieth Century". In Michael D. C. Drout (ed.). J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 109–110. ISBN 978-0-415-96942-0.

- Milner, Liz (2003). "Brian Rosebury's Tolkien: A Cultural Phenomenon". The Green Man Review. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- Patterson, Nancy-Lou (1997). "Reviews: Sensuous Precision Brian Rosebury, Tolkien — A Critical Assessment". Mythlore. 21 (4 (82, Winter 1997)). article 8.

- Rosebury, Brian (2003) [1992]. Tolkien : A Cultural Phenomenon. Palgrave. ISBN 978-1403-91263-3.

- Turner, Allan (2013) [2007]. "Prose Style". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 545–546. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

.jpg)