Merry Brandybuck

Meriadoc Brandybuck, usually called Merry, is a fictional character from J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth legendarium, featured throughout his most famous work, The Lord of the Rings. Merry is described as one of the closest friends of Frodo Baggins, the main protagonist. Merry and his friend Pippin are members of the Fellowship of the Ring. They become separated from the rest of the group and spend much of The Two Towers making their own decisions. By the time of The Return of the King, Merry has enlisted in the army of Rohan as an esquire to King Théoden, in whose service he fights during the War of the Ring. After the war, he returns home, where he and Pippin lead the Scouring of the Shire, ridding it of Saruman's influence.

| Meriadoc Brandybuck | |

|---|---|

| In-universe information | |

| Aliases | Merry, Master of Buckland |

| Race | Hobbit |

| Affiliation | Company of the Ring |

| Book(s) | The Lord of the Rings |

Commentators have noted that his and Pippin's actions serve to throw light on the characters of the good and bad Germanic lords Theoden and Denethor, Steward of Gondor, while their simple humour acts as a foil for the higher romance involving kings and the heroic Aragorn.

Merry appeared in the animated film of Lord of the Rings by Ralph Bakshi, the animated version of The Return of the King by Rankin/Bass, and in the live action film series by Peter Jackson.

Fictional history

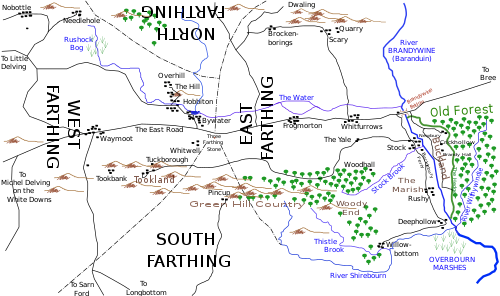

Meriadoc Brandybuck, a hobbit, known as Merry, was the only child of Saradoc Brandybuck, a Master of Buckland, and Esmeralda Brandybuck (née Took), the younger sister of Paladin Took II, making him a cousin to Paladin's son, his friend Peregrin (Pippin) Took.[T 2] Hobbits of the Shire saw Bucklanders as "peculiar, half foreigners as it were"; the Bucklanders were the only hobbits comfortable with boats; and living next to the Old Forest, protected from it only by a high hedge, they locked their doors after dark, unlike hobbits in the Shire.[T 1]

Long before Bilbo Baggins left the Shire, Merry knew of the One Ring and its power of invisibility. He guarded Bag End after Bilbo's party, protecting Frodo from unwanted guests.[T 3] Merry was a force behind "the Conspiracy" of Sam, Pippin, Fredegar Bolger and himself to help Frodo. [T 1] He assembled the company's packs and brought ponies.[T 4] His shortcut through the Old Forest distanced them from the Black Riders, the Nazgûl, for a time.[T 5] In the Barrow-downs, he is given his sword, a dagger forged in the kingdom of Arnor.[T 6] Arriving at Bree, Merry was not celebrating in the Prancing Pony when Frodo put on the Ring; he was outside taking a solitary walk, and was nearly overcome by a Nazgûl.[1][T 7] At Rivendell, he was seen studying maps and plotting their path. Elrond reluctantly admitted him and Pippin to the Company of the Ring.[T 8]

Halted at the entrance to Moria, Merry asked Gandalf the meaning of the door inscription "Speak, friend, and enter". When Gandalf, having unsuccessfully tried many door-opening spells, discovered the true interpretation, he said "Merry, of all people, was on the right track".[T 9] At Amon Hen, the Hill of Seeing, the Company hesitated in confusion, and scattered. Merry and Pippin were captured by a band of Saruman's Uruk-hai, despite Boromir's defence.[T 10] Escaping with Pippin into Fangorn forest, they were rescued by the leader of the Ents, Treebeard, and given an Ent-draught to drink: it made them both grow unnaturally tall for hobbits.[T 11] Accompanying Treebeard to the Entmoot and later to the wizard Saruman's fortress of Isengard, which the ents destroyed, they took up residence in a gate-house, meeting King Théoden of Rohan, and were reunited with the Fellowship.[T 12][2] Merry swore allegiance to Théoden and became his esquire.[T 13] Against Théoden's orders, he rode to Gondor with the King's niece Éowyn, who disguised herself as a common soldier.[T 14] In the Battle of the Pelennor Fields, while the leader of the Nazgûl was preoccupied with Éowyn, Merry stabbed him behind his knee. The Black Captain stumbled, and Éowyn killed him. This fulfilled the prophecy that he would not be killed "by the hand of man," as it was a hobbit and a woman that ended his life.[T 15] Éomer made Meriadoc a Knight of the Mark for his bravery.[1]

After the War of the Ring, Merry and Pippin returned home as the tallest of hobbits, only to find that Saruman had taken over the Shire. Merry and Pippin roused the hobbits to revolt. During the resulting Scouring of the Shire, Merry commanded the hobbit forces, and killed the leader of Saruman's "ruffians" at the Battle of Bywater.[1][T 16] Merry inherited the title Master of Buckland at the start of the Fourth Age. He became a historian of the Shire.[T 17][T 18] At the age of 102, Merry returned to Rohan and Gondor with Pippin; they died in Gondor, and were laid to rest among the Kings of Gondor in Rath Dínen, then moved to lie next to Aragorn. His son succeeded him as Master of Buckland.[T 19]

Development

Early in the development of the story, the hobbit was named as Marmaduke Brandybuck.[T 20]

Reception

The critic Jane Chance Nitzsche discusses the role of Merry and his friend Pippin in illuminating the contrast between the "good and bad Germanic lords Theoden and Denethor". She writes that both leaders receive the allegiance of a hobbit, but very differently: Theoden, King of Rohan, treats Merry with love, which is reciprocated, whereas Denethor, Steward of Gondor, undervalues Pippin because he is small, and binds him with a harsh formal oath.[3]

The critic Tom Shippey notes that Tolkien uses the two hobbits and their low simple humour as foils for the much higher romance to which he was aspiring with the more heroic and kingly figures of Theoden, Denethor, and Aragorn: an unfamiliar and old-fashioned writing style that might otherwise, Shippey writes, have lost his readers entirely.[4] He notes that Merry and Pippin serve, too, as guides to introduce the reader to seeing the various non-human characters, letting the reader know that an ent looks like an old tree stump or "almost like the figure of some gnarled old man".[5] The two apparently minor hobbits have another role, Shippey writes: it is to remain of good courage when even strong men start to doubt whether victory is possible, as when Merry encourages Theoden when even he seems to be succumbing to "horror and doubt".[6]

Another purpose, notes the Tolkien critic Paul Kocher, is given by Tolkien himself, in the words of the wizard Gandalf: "the young hobbits ... were brought to Fangorn, and their coming was like the falling of small stones that starts an avalanche in the mountains."[7] Kocher observes that Tolkien is describing Merry and Pippin's role in the same terms as he spells out Gollum's purpose and Gandalf's "reincarnation"; in Kocher's words, the "finger of Providence"[7] can be glimpsed: "All are filling roles written for them by the same great playwright."[7]

The Tolkien critic David Day writes that Tolkien particularly disliked Shakespeare's treatment of myth, and must have resolved to do better. Day compares Tolkien's prophecy "not by the hand of man will [the Witch-king of Angmar] fall" to Shakespeare's account of Macbeth, who should "laugh to scorn / The power of man, for none of woman born / Shall harm Macbeth" (Act 4, scene 1): Macbeth is killed by one who "was from his mother's womb / Untimely ripp'd" (as Macduff was born by Caesarean section: Act 5, scene 8). In both cases, the prophecies are at once true and false: Macduff was a living man, but not strictly born; while Éowyn and Merry were not men, but woman and hobbit, in Day's view a distinctly better solution than Shakespeare's.[8]

Adaptations

In Ralph Bakshi's 1978 animated version of The Lord of the Rings, Merry was voiced by Simon Chandler.[9] In the 1980 Rankin/Bass animated version of The Return of the King, made for television, the character was voiced by the radio personality Casey Kasem.[10] In the 1981 BBC radio serial of The Lord of the Rings, Merry was played by Richard O'Callaghan.[11] He was portrayed by Jarmo Hyttinen in the 1993 Finnish miniseries Hobitit.[12] In Peter Jackson's 2001–2003 film trilogy adaptation of the books, Merry was portrayed by Dominic Monaghan as a cheerful prankster full of fun and practical jokes.[13]

References

Primary

- This list identifies each item's location in Tolkien's writings.

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 1, ch. 5 "A Conspiracy Unmasked"

- The Return of the King, Appendix C, "Family Trees"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 1, ch. 1 "A Long-expected Party"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 1, ch. 4 "A Short Cut to Mushrooms"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 1, ch. 6 "The Old Forest"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 1, ch. 8 "Fog on the Barrow-downs"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 1, ch. 10 "Strider"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 2, ch. 3 "The Ring goes South"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 2, ch. 4 "A Journey in the Dark"

- The Two Towers, book 3, ch. 3 "The Uruk-hai"

- The Two Towers, book 3, ch. 4 "Treebeard"

- The Two Towers, book 3, ch. 8 "The Road to Isengard"

- The Two Towers, book 5, ch. 2 "The Passing of the Grey Company"

- The Return of the King, book 5, ch. 3 "The Muster of Rohan"

- The Return of the King, book 5, ch. 6 "The Battle of the Pelennor Fields"

- The Return of the King, book 6 ch. 8 "The Scouring of the Shire"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, Prologue, "Note on the Shire Records"

- The Two Towers, book 3, ch. 9 "Flotsam and Jetsam"

- The Return of the King, Appendix B, "Later Events Concerning the Members of the Fellowship of the Ring," entry for 1484

- The Return of the Shadow, "The First Phase", I. "A Long-expected Party", (iii) "The Third Version"

Secondary

- Croft 2006, pp. 419–420.

- Croft 2006, pp. 511-512.

- Nitzsche 1980, pp. 119-122.

- Shippey 2005, pp. 238-240.

- Shippey 2005, p. 151.

- Shippey 2005, p. 180.

- Kocher 1974, pp. 44-45.

- Day, David (2019). Macbeth. A Dictionary of Sources of Tolkien. Octopus. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-7537-3406-3.

- Canby, Vincent (1978). "The Lord of the Rings". The New York Times.

- Day, Patrick Kevin (16 June 2014). "Shaggy, Merry and more: Casey Kasem's greatest cartoon voices". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- "Riel Radio Theatre — The Lord of the Rings, Episode 2". Radioriel. 15 January 2009. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- Robb, Brian J.; Simpson, Paul (2013). Middle-earth Envisioned: The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings: On Screen, On Stage, and Beyond. Race Point Publishing. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-937994-27-3.

- Ebert, Roger (2004). Roger Ebert's Movie Yearbook 2005. Andrews McMeel Publishing. p. 395. ISBN 978-0-7407-4742-7.

Sources

- Croft, Janet Brennan (2006). "Merry". J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. pp. 419–420. ISBN 1-135-88034-4.

- Kocher, Paul (1974) [1972]. Master of Middle-Earth: The Achievement of J.R.R. Tolkien. Penguin Books. ISBN 0140038779.

- Nitzsche, Jane Chance (1980) [1979]. Tolkien's Art. Papermac. ISBN 0-333-29034-8.

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). Grafton (HarperCollins). ISBN 978-0261102750.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954), The Fellowship of the Ring, The Lord of the Rings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 1987), ISBN 0-395-08254-4

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954), The Two Towers, The Lord of the Rings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 1987), ISBN 0-395-08254-4

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1955), The Return of the King, The Lord of the Rings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 1987), ISBN 0-395-08256-0

.jpg)