Audiobook

An audiobook (or a talking book) is a recording of a book or other work being read out loud. A reading of the complete text is described as "unabridged", while readings of a shorter version are an abridgement.

Spoken audio has been available in schools and public libraries and to a lesser extent in music shops since the 1930s. Many spoken word albums were made prior to the age of cassettes, compact discs, and downloadable audio, often of poetry and plays rather than books. It was not until the 1980s that the medium began to attract book retailers, and then book retailers started displaying audiobooks on bookshelves rather than in separate displays.

Etymology

The term "talking book" came into being in the 1930s with government programs designed for blind readers, while the term "audiobook" came into use during the 1970s when audiocassettes began to replace records.[1] In 1994, the Audio Publishers Association established the term "audiobook" as the industry standard.[1]

History

Spoken word recordings first became possible with the invention of the phonograph by Thomas Edison in 1877.[1] "Phonographic books" were one of the original applications envisioned by Edison which would "speak to blind people without effort on their part."[1] The initial words spoken into the phonograph were Edison's recital of "Mary Had a Little Lamb", the first instance of recorded verse.[1] In 1878, a demonstration at the Royal Institution in Britain included "Hey Diddle Diddle, the Cat and the Fiddle" and a line of Tennyson's poetry thus establishing from the very beginning of the technology its association with spoken literature.[1]

United States

Beginnings to 1970

Many short, spoken word recordings were sold on cylinder in the late 1800s and early 1900s,[2] however the round cylinders were limited to about 4 minutes each making books impractical;[1] flat platters increased to 12 minutes but this too was impractical for longer works.[1] "One early listener complained that he would need a wheelbarrow to carry around talking books recorded on discs with such limited storage capacity."[1] By the 1930s close-grooved records increased to 20 minutes making possible longer narrative.[1]

In 1931, the American Foundation for the Blind (AFB) and Library of Congress Books for the Adult Blind Project established the "Talking Books Program" (Books for the Blind), which was intended to provide reading material for veterans injured during World War I and other visually impaired adults.[1] The first test recordings in 1932 included a chapter from Helen Keller's Midstream and Edgar Allan Poe's "The Raven".[1] The organization received congressional approval for exemption from copyright and free postal distribution of talking books.[1] The first recordings made for the Talking Books Program in 1934 included sections of the Bible; the Declaration of Independence and other patriotic documents; plays and sonnets by Shakespeare; and fiction by Gladys Hasty Carroll, E. M. Delafield, Cora Jarrett, Rudyard Kipling, John Masefield, and P. G. Wodehouse.[1]

Recording for the Blind & Dyslexic (RFBD, later renamed Learning Ally) was founded in 1948 by Anne T. Macdonald, a member of the New York Public Library's Women's Auxiliary, in response to an influx of inquiries from soldiers who had lost their sight in combat during World War II. The newly passed GI Bill of Rights guaranteed a college education to all veterans, but texts were mostly inaccessible to the recently blinded veterans, who did not read Braille and had little access to live readers. Macdonald mobilized the women of the Auxiliary under the motto "Education is a right, not a privilege". Members of the Auxiliary transformed the attic of the New York Public Library into a studio, recording textbooks using then state-of-the-art six-inch vinyl SoundScriber phonograph discs that played approximately 12 minutes of material per side. In 1952, Macdonald established recording studios in seven additional cities across the United States.

Caedmon Records was a pioneer in the audiobook business, it was the first company dedicated to selling spoken work recordings to the public and has been called the "seed" of the audiobook industry.[3] Caedmon was formed in New York in 1952 by college graduates Barbara Holdridge and Marianne Roney.[3] Their first release was a collection of poems by Dylan Thomas as read by the author.[3] The LP's B-side contained A Child's Christmas in Wales which was added as an afterthought - the story was obscure and Thomas himself couldn't remember its title when asked what to use to fill up the B-side - but this recording went on to become one of his most loved works, and launched Caedmon into a successful company.[3] The original 1952 recording was a selection for the 2008 United States National Recording Registry, stating it is "credited with launching the audiobook industry in the United States".[4] Caedmon used LP records, invented in 1948, which made longer recordings more affordable and practical, however most of their works were poems, plays and other short works, not unabridged books due to the LP's limitation of about a 45-minute playing time (combined sides).

Listening Library[5] was also a pioneering company, it was one of the first to distribute children's audiobooks to schools, libraries and other special markets, including VA hospitals.[6] It was founded by Anthony Ditlow and his wife in 1955 in their Red Bank, New Jersey home; Ditlow was partially blind.[6] Another early pioneering company was Spoken Arts founded in 1956 by Arthur Luce Klein and his wife, they produced over 700 recordings and were best known for poetry and drama recordings used in schools and libraries.[7] Like Caedemon, Listening Library and Spoken Arts benefited from the new technology of LPs, but also increased governmental funding for schools and libraries beginning in the 1950s and 60s.[6]

1970 to 1996

Though spoken recordings were popular in 33⅓ vinyl record format for schools and libraries into the early 1970s, the beginning of the modern retail market for audiobooks can be traced to the wide adoption of cassette tapes during the 1970s.[8] Cassette tapes were invented in 1962 and a few libraries, such as the Library of Congress, began distributing books on cassette by 1969.[8] However, during the 1970s, a number of technological innovations allowed the cassette tape wider usage in libraries and also spawned the creation of new commercial audiobook market.[8] These innovations included the introduction of small and cheap portable players such as the Walkman, and the widespread use of cassette decks in cars, particularly imported Japanese models which flooded the market during the multiple energy crises of the decade.[8]

In the early 1970s, instructional recordings were among the first commercial products sold on cassette.[8] There were 8 companies distributing materials on cassette with titles such as Managing and Selling Companies (12 cassettes, $300) and Executive Seminar in Sound on a series of 60-minute cassettes.[8] In libraries, most books on cassette were still made for the blind and handicapped, however some new companies saw the opportunity for making audiobooks for a wider audience, such as Voice Over Books which produced abridged best-sellers with professional actors.[8] Early pioneers included Olympic gold medalist Duvall Hecht who in 1975 founded the California-based Books on Tape as a direct to consumer mail order rental service for unabridged audiobooks and expanded their services selling their products to libraries and audiobooks gaining popularity with commuters and travelers.[8] In 1978, Henry Trentman, a traveling salesman who listened to sales tapes while driving long distances, had the idea to create quality unabridged recordings of classic literature read by professional actors.[9] His company, the Maryland-based Recorded Books, followed the model of Books on Tape but with higher quality studio recordings and actors.[9] Recorded Books and Chivers Audio Books were the first to develop integrated production teams and to work with professional actors.[10]

By 1984, there were eleven audiobook publishing companies, they included Caedmon, Metacom, Newman Communications, Recorded Books, Brilliance and Books on Tape.[8] The companies were small, the largest had a catalog of 200 titles.[8] Some abridged titles were being sold in bookstores, such as Walden Books, but had negligible sales figures, many were sold by mail-order subscription or through libraries.[8] However, in 1984, Brilliance Audio invented a technique for recording twice as much on the same cassette thus allowing for affordable unabridged editions.[8] The technique involved recording on each of the two channels of each stereo track.[8] This opened the market to new opportunities and by September 1985, Publishers Weekly identified twenty-one audiobook publishers.[8] These included new major publishers such as Harper and Row, Random House, and Warner Communications.[8]

1986 has been identified as the turning point in the industry, when it matured from an experimental curiosity.[8] A number of events happened: the Audio Publishers Association, a professional non-profit trade association, was established by publishers who joined together to promote awareness of spoken word audio and provide industry statistic.[8] Time-Life began offering members audiobooks.[8] Book-of-the-Month club began offering audiobooks to its members, as did the Literary Guild. Other clubs such as the History Book Club, Get Rich Club, Nostalgia Book Club, Scholastic club for children all began offering audiobooks.[8] Publishers began releasing religious and inspirational titles in Christian bookstores. By May 1987, Publishers Weekly initiated a regular column to cover the industry.[8] By the end of 1987, the audiobook market was estimated to be a $200 million market, and audiobooks on cassette were being sold in 75% of regional and independent bookstores surveyed by Publishers Weekly.[8] By August 1988 there were forty audiobook publishers, about four times as many as in 1984.[8]

By the middle of the 1990s, the audio publishing business grew to 1.5 billion dollars a year in retail value.[11] In 1996, the Audio Publishers Association established the Audie Awards for audiobooks, which is equivalent to the Oscar for the audiobook industry. The nominees are announced each year by February. The winners are announced at a gala banquet in May, usually in conjunction with BookExpo America.[12]

1996 to present

With the spread of the Internet to consumers in the 1990s, faster download speeds with broadband technologies, new compressed audio formats and portable media players, the popularity of audiobooks increased significantly during the late 1990s and 2000s. In 1997, Audible pioneered the world's first mass-market digital media player, named "The Audible Player",[13] it retailed for $200, held 2 hours of audio and was touted as being "smaller and lighter than a Walkman", the popular cassette player used at the time.[14] Digital audiobooks were a significant new milestone as they allowed listeners freedom from physical media such as cassettes and CD-ROMs which required transportation through the mail, allowing instead instant download access from online libraries of unlimited size, and portability using comparatively small and lightweight devices. Audible.com was the first to establish a website, in 1998, from which digital audiobooks could be purchased.

Another innovation was the creation of LibriVox in 2005 by Montreal-based writer Hugh McGuire who posed the question on his blog: "Can the net harness a bunch of volunteers to help bring books in the public domain to life through podcasting?" Thus began the creation of public domain audiobooks by volunteer narrators. By the end of 2017, LibriVox had a catalog of over 12,000 works and was producing about 1,000 per year.[15]

The transition from vinyl, to cassette, to CD, to MP3CD, to digital download has been documented by Audio Publishers Association in annual surveys (the earlier transition from record to cassette is described in the section on the 1970s). The final year that cassettes represented greater than 50% of total market sales was 2002.[16] Cassettes were replaced by CDs as the dominant medium during 2003-2004. CDs reached a peak of 78% of sales in 2008,[17] then began to decline in favor of digital downloads. The 2012 survey found CDs accounted for "nearly half" of all sales meaning it was no longer the dominate medium (APA did not report the digital download figures for 2012, but in 2011 CDs accounted for 53% and digital download was 41%).[18][19] The APA estimates that audiobook sales in 2015 in digital format increased by 34% over 2014.[20]

The resurgence of audio storytelling is widely attributed to advances in mobile technologies such as smartphones, tablets, and multimedia entertainment systems in cars, also known as connected car platforms.[21][22] Audio drama recordings are also now podcast over the internet.[23]

In 2014, Bob & Debra Deyan of Deyan Audio opened the Deyan Institute of Vocal Artistry and Technology, the world's first campus and school for teaching the art and technology of audiobook production.[24]

In 2018, approximately 50,000 audiobooks were recorded in the United States with a sales growth of 20 percent year over year.[25]

Germany

The evolution and use of audiobooks in Germany closely parallels that of the US. A special example of its use is the West German Audio Book Library for the Blind, founded in 1955. Actors from the municipal theater in Münster recorded the first audio books for the visually impaired in an improvised studio lined with egg cartons. Because trams rattled past, these first productions took place at night. Later, texts were recorded by trained speakers in professional studios and distributed to users by mail. Until the 1970s recordings were on tape reels, then later cassettes. Since 2004, the offerings have been recorded in the DAISY Digital Talking Book MP3 standard, which provides additional features for visually impaired users to both listen and navigate written material aurally.[26]

India

Audiobooks in India started to appear somewhat later than in the rest of the world. Only by 2010 did Audiobooks gain mainstream popularity in the Indian market. This is primarily due to lack of previous organized efforts on the part of publishers and authors. The marketing efforts and availability of Audiobooks has made India as one of the fastest growing Audiobooks markets in the world.

The lifestyle of urban Indian population and one of the highest daily commute time in the world has also helped in making Audiobooks popular in the region. Business and Self Help books have widespread appeal and have been more popular than fiction/non-fiction. This is because Audiobooks are primarily seen as an avenue for self-improvement and education, rather than entertainment.

Audio books are being released in various Indian languages. In Malayalam, the first audio novel, titled Ouija Board, was released by Kathacafe in 2018.[27] Now Indian companies are working towards Audio Books generation in the Indian Vernacular Languages. Listen Stories By Sahitya Chintan is an Android audio book library allowing listing 1000+ Hindi Audio Books. They are offering ample audio books freely. To access the entire catalog they are charging nominal membership of Rs. 199/ Year for Indian audio book listener and $5.99/Year for Rest of World.

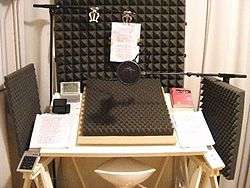

Production

Producing an audiobook consists of a narrator sitting in a recording booth reading the text, while a studio engineer and a director record and direct the performance.[28] If a mistake is made the recording is stopped and the narrator reads it again.[28] With recent advancements in recording technology, many audiobooks are also now recorded in home studios by narrators working independently.[29] Audiobooks produced by major publishing houses undergo a proofing and editing process after narration is recorded.

Narrators are usually paid on a finished recorded hour basis, meaning if it took 20 hours to produce a 5-hour book, the narrator is paid for 5 hours, thus providing an incentive not to make mistakes.[28] Depending on the narrator they are paid US$150 per finished hour to US$400 (as of 2011).[28] The overall cost to produce an audiobook can vary significantly, as longer books require more studio time and more well known narrators come at a premium. According to a representative at Audible, the cost of recording an audiobook has fallen from around US$25,000 in the late 1990s to around US$2,000-US$3,000 in 2014.[30]

Formats

Audiobooks are distributed on any audio format available, but primarily these are records, cassette tapes, CDs, MP3 CDs, downloadable digital formats (e.g., MP3 (.mp3), Windows Media Audio (.wma), Advanced Audio Coding (.aac)), and solid state preloaded digital devices in which the audio content is preloaded and sold together with a hardware device.

In 1955, a German inventor introduced the Sound Book cassette system based on the Tefifon format where instead of a magnetic tape the sound was recorded on a continuous loop of grooved vinylite ribbon similar to the old 8-track tape. Even though the original Tefifon upon which it was based ran at 19 CPS and could hold a maximum of 4 hours, one Sound Book could hold eight hours of recordings as it ran at half the speed or 9.5 CPS. However, just like the Tefifon, the format never became widespread in use.[31]

A small number of books are recorded for radio broadcast, usually in abridged form and sometimes serialized, notably National Public Radio's broadcast of Star Wars and several projects by the BBC. Audiobooks may come as fully dramatized versions of the printed book, sometimes calling upon a complete cast, music, and sound effects. Effectively audio dramas, these audiobooks are known as full cast audio books. BBC radio stations Radio 3, Radio 4, and Radio 4 Extra have broadcast such productions as the William Gibson novel Neuromancer.[32]

An audio first production is a spoken word audio work that is an original production but not based on a book. Examples include Joe Hill, the son of Stephen King, who released a Vinyl First audiobook called Dark Carousel in 2018. It came in a 2-LP vinyl set, or as a downloadable MP3, but with no published text.[33] Another example includes Spin, The Audiobook Musical (2018), a musical rendition of Rumpelstiltskin narrated by Jim Dale, and featuring a cast of Broadway musical stars.[34]

Use

Audiobooks have been used to teach children to read and to increase reading comprehension. They are also useful for the blind. The National Library of Congress in the U.S. and the CNIB Library in Canada provide free audiobook library services to the visually impaired; requested books are mailed out (at no cost) to clients. Founded in 1996, Assistive Media of Ann Arbor, Michigan was the first organization to produce and deliver spoken-word recordings of written journalistic and literary works via the Internet to serve people with visual impairments.

About 40 percent of all audiobook consumption occurs through public libraries, with the remainder served primarily through retail book stores. Library download programs are currently experiencing rapid growth (more than 5,000 public libraries offer free downloadable audio books). Libraries are also popular places to check out audio books in the CD format.[35] According to the National Endowment for the Arts' study, "Reading at Risk: A Survey of Literary Reading in America" (2004), audiobook listening is one of very few "types" of reading that is increasing general literacy.[36]

Listening practices

Audiobooks are considered a valuable tool because of their format. Unlike traditional books or a video program, one can listen to an audiobook while doing other tasks. Such tasks include doing the laundry, exercising, weeding and similar activities. The most popular general use of audiobooks by adults is when commuting with an automobile or while traveling with public transport, as an alternative to radio. Many people listen as well just to relax or as they drift off to sleep.

A recent survey released by the Audio Publishers Association found that the overwhelming majority of audiobook users listen in the car, and more than two-thirds of audiobook buyers described audiobooks as relaxing and a good way to multitask. Another stated reason for choosing audiobooks over other formats is that an audio performance makes some books more interesting.[37]

Common practices include:

- Replaying: Depending upon one's degree of attention and interest, it is often necessary to listen to segments of an audiobook more than once to allow the material to be understood and retained satisfactorily. Replaying may be done immediately or after extended periods of time.

- Learning: People may listen to an audiobook (usually an unabridged one) while following along in an actual book. This helps them to learn words that they may not learn correctly if they were only to read the book. This can also be a very effective way to learn a new language.

- Multitasking: Many audiobook listeners choose the format because it allows multitasking during otherwise mundane or routine tasks such as exercising, crafting, or cooking.

- Entertainment: Audiobooks have become a popular form of travel entertainment for families or commuters.[38]

Charitable and nonprofit organizations

Founded in 1948, Learning Ally serves more than 300,000 K-12, college and graduate students, veterans and lifelong learners – all of whom cannot read standard print due to blindness, visual impairment, dyslexia, or other learning disabilities. Learning Ally's collection of more than 80,000 human-narrated textbooks and literature titles can be downloaded on mainstream smartphones and tablets, and is the largest of its kind in the world.

Founded in 2002, Bookshare is an online library of computer-read audiobooks in accessible formats for people with print disabilities.

Founded in 2005, LibriVox is also an online library of downloadable audiobooks and a free non for profit organisation developed by Hugh McGuire. It has audiobooks in several languages. Most of their languages are typically Western European languages. [39]

Calibre Audio Library is a UK charity providing a subscription-free service of unabridged audiobooks for people with sight problems, dyslexia or other disabilities, who cannot read print. They have a library of over 8,550 fiction and non-fiction titles which can be borrowed by post on MP3 CDs and memory sticks or via streaming.[40]

Listening Books is a UK audiobook charity providing an internet streaming, download and postal service to anyone who has a disability or illness which makes it difficult to hold a book, turn its pages, or read in the usual way, this includes people with visual, physical, learning or mental health difficulties. They have audiobooks for both leisure and learning and a library of over 7,500 titles which are recorded in their own digital studios or commercially sourced.

The Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB) is a UK charity which offers a Talking Books library service. The audio books are provided in DAISY format and delivered to the reader's house by post as a CD or USB memory stick. There are over 30,000 audio books available to borrow, which are free to print disabled library members. RNIB subsidises the Talking Books service by around £4 million a year.[41]

See also

References

- Matthew Rubery, ed. (2011). "Introduction". Audiobooks, Literature, and Sound Studies. Routledge. pp. 1–21. ISBN 978-0-415-88352-8.

- "Cylinder Recordings". Cyberbee.com. Retrieved 2012-08-02.

- "Caedmon: Recreating the Moment of Inspiration". NPR Morning Edition. December 5, 2002. Archived from the original on March 7, 2014. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- "The National Recording Registry 2008". National Recording Preservation Board of the Library of Congress. The Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- "Kids and Teens". Archived from the original on November 4, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- Shannon Maughan (March 7, 2005). "Sounds Like Celebration". Publishers Weekly. Archived from the original on March 19, 2014. Retrieved March 19, 2014.

- "Arthur Klein, 81. Made Literary Recordings". The New York Times. April 21, 1997. Archived from the original on March 30, 2014. Retrieved March 19, 2014.

- Virgil L. P. Blake (1990). "Something New Has Been Added: Aural Literacy and Libraries". Information Literacies for the Twenty-First Century. G. K. Hall & Co. pp. 203–218. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- John Blades (May 21, 1991). "The Olivier Of Books On Audio Tape". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on January 13, 2014. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

- "A Brief History of Audio Books". Booksalley.com. 2007-09-18. Archived from the original on 2011-10-28. Retrieved 2012-08-02.

- Hendren, John (August 29, 1995). "Recorded Books: Winning War With Rush-Hour Traffic : Commuting: Henry Trentman says his audio books are the 'world's greatest tranquilizer' for stressed-out drivers". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. Archived from the original on January 12, 2014. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

- "Audie Award". Booksalley.com. Archived from the original on 2011-10-28. Retrieved 2012-08-02.

- "Progressive Networks and Audible Inc. Team Up to Make RealAudio Mobile". Audible.com. September 15, 1997. Archived from the original on January 18, 1998. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- "The Audible Player". Audible.com. 1997. Archived from the original on January 18, 1998. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- MaryAnnSpiegel (January 1, 2018). "LibriVox stats". LibriVox. Archived from the original on January 23, 2018. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Audio Publishers Association Fact Sheet Archived October 26, 2010, at the Wayback Machine (also includes some historical perspective in the 1950s by Marianne Roney)

- Kaitlin Friedmann (September 15, 2008). "More Americans Are All Ears To Audiobooks" (PDF). Audio Publishers Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 21, 2015. Retrieved March 19, 2014.

- The Audio Publishers Association (November 21, 2013). "Audibooks Industry Showing Enormous Growth" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- "Industry Data". Audio Publishers Association. Archived from the original on March 19, 2014. Retrieved March 19, 2014.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-06-09. Retrieved 2016-09-09.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) APA, May 23, 2016

- Roose, Kevin (October 3, 2014). "What's Behind the Great Podcast Renaissance?". New York. Archived from the original on July 15, 2015. Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- Kang, Cecilia (September 25, 2014). "Podcasts are back — and making money". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 23, 2015. Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- Purcell, Julius (March 27, 2015). "The resurgence of audio drama". Financial Times. Archived from the original on July 23, 2015. Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- Mary Burkey (March 13, 2014). "Elevating the Art of the Audiobook: Deyan Institute of Voice Artistry & Technology". Booklist. Archived from the original on June 13, 2014. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- Fitzpatrick, Molly (2018-05-30). "Portrait of the Voice in My Head". The Village Voice. Retrieved 2018-05-31.

- Sabine Tenta: The Audible Gate to the World: The West German Audio Book Library for the Blind (Goethe-Institut, 2009) online Archived 2011-01-27 at the Wayback Machine (in English) retrieved 26-May-2012

- "First Malayalam audio novel 'Ouija Board' launched". newindianexpress.com. Archived from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ALLEN PIERLEONI. "The right voice can send an audiobook up the charts", McClatchy Newspapers, June 29, 2011.

- "Narrator Resources". Audio Publishers Association. Archived from the original on 2014-10-28. Retrieved 2014-10-28.

- "From Papyrus to Pixels". The Economist. December 2014. Archived from the original on January 3, 2015. Retrieved December 26, 2014.

- "Grooved Tape Recording Plays For Eight Hours." Archived 2015-04-07 at the Wayback Machine Popular Mechanics, July 1955, p. 141.

- "William Gibson's Seminal Cyberpunk Novel, Neuromancer, Dramatized for Radio (2002)". Open Culture. Archived from the original on 6 February 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- Michael Kozlowski (February 20, 2018). "Joe Hill is creating a Vinyl First Audiobook". Good E-Reader. Archived from the original on February 21, 2018. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- Michael Kozlowski (December 17, 2018). "Global Audiobook Trends and Statistics for 2018". Good E-Reader. Archived from the original on February 21, 2018. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- "New Audio". Hclib.org. 2012-06-15. Archived from the original on 2012-02-15. Retrieved 2012-08-02.

- National Endowment for the Arts (June 2004). "Reading at Risk: A Survey of Literary Reading in America (Research Division Report #46)". Archived from the original on 2014-06-04.

- "Audiobooks: Billion-Dollar Industry Shows Steady Growth". PW's Audiobook Blog. 2013-02-25. Archived from the original on 2014-10-28. Retrieved 2014-10-28.

- "What Kind of Listener Are You?". Random House Audio. Archived from the original on 2014-10-28. Retrieved 2014-10-28.

- "About Librivox". Librivox.org. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2015-12-09.

- "Calibre services". calibre.org.uk. 2013-03-28. Archived from the original on 2012-03-28. Retrieved 2012-03-28.

- "RNIB Talking Books Service". Rnib.org.uk. 2012-06-08. Archived from the original on 2012-07-24. Retrieved 2012-08-02.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Audiobooks. |

- Alexandra Alter (August 1, 2013). "The New Explosion in Audio Books". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- Jeremy Olshan (December 8, 2015). "Why some audiobooks sell four times as well as their print versions". Marketwatch (WSJ)'. Retrieved December 8, 2015.