Jurassic Park (novel)

Jurassic Park is a 1990 science fiction novel written by Michael Crichton.[2] A cautionary tale about genetic engineering, it presents the collapse of an amusement park showcasing genetically re-created dinosaurs to illustrate the mathematical concept of chaos theory and its real world implications. A sequel titled The Lost World, also written by Crichton, was published in 1995. In 1997, both novels were re-published as a single book titled Michael Crichton's Jurassic World (unrelated to the 2015 film of the same name).[3][4][5]

First edition cover | |

| Author | Michael Crichton |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Chip Kidd |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Publisher | Alfred A. Knopf |

Publication date | November 20, 1990[1] |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover and Paperback) |

| Pages | 448 |

| ISBN | 0-394-58816-9 |

| OCLC | 22511027 |

| 813/.54 20 | |

| LC Class | PS3553.R48 J87 1990 |

| Followed by | The Lost World |

In 1993, Steven Spielberg adapted the book into the blockbuster film Jurassic Park. The book's sequel, The Lost World, was also adapted by Spielberg into a film in 1997. A third film, directed by Joe Johnston and released in 2001, drew several elements, themes, and scenes from both books that were ultimately not utilized in either of the previous films, such as the aviary and boat scenes.

The novel began as a screenplay Crichton wrote in 1983, about a graduate student who recreates a dinosaur.[6] Eventually, given his reasoning that genetic research is expensive and "there is no pressing need to create a dinosaur", Crichton concluded that it would emerge from a "desire to entertain", leading to a wildlife park of extinct animals.[7] Originally, the story was told from the point of view of a child, but Crichton changed it as everyone who read the draft felt it would be better if told by an adult.[8]

Plot summary

In 1989, a series of strange animal attacks occur in Costa Rica and on the nearby fictional island of Isla Nublar,[9] the story's main setting, one of which is a worker severely injured on a construction project on Isla Nublar, whose employers refuse to disclose any information about. One of the species behind the attacks is eventually identified as a Procompsognathus. Paleontologist Alan Grant and his paleobotanist graduate student, Ellie Sattler, are contacted to confirm the identification, but are abruptly whisked away by billionaire John Hammond — founder and chief executive officer of International Genetic Technologies, or InGen — for a weekend visit to a "biological preserve" he has established on Isla Nublar.

Upon arrival, the preserve is revealed to be Jurassic Park, a theme park showcasing cloned dinosaurs. The animals have been recreated using damaged dinosaur DNA found in blood inside of gnats, ticks, and mosquitoes fossilized and preserved in amber. Gaps in the genetic code have been filled in with "compatible" reptilian, avian or amphibian DNA. To control the population, all specimens on the island are lysine-deficient and X-Ray sterilized females. Hammond proudly touts InGen's advances in genetic engineering and shows his guests through the island's vast array of automated systems.

Recent incidents in the park have spooked Hammond's investors. To placate them, Hammond uses Grant and Sattler as fresh consultants. They stand in counterbalance to a famous mathematician and chaos theorist, Ian Malcolm, and a lawyer representing the investors, Donald Gennaro, who are pessimistic about the park's prospects. Malcolm, having been consulted before the park's creation, is especially emphatic in his prediction that the park will collapse, as it is an unsustainable simple structure bluntly forced upon a complex system with too many unpredictable variables, such as an uncontrollable population, attempting to contain animals with no real equivalent to extant animals with no predictable behavior patterns, and an untested computer system that continually fails to monitor and feed the population.

Countering Malcolm's dire predictions with youthful energy, Hammond groups the consultants with his grandchildren, Tim and Alexis "Lex" Murphy. While touring the park, Grant finds a Velociraptor eggshell, seemingly proving Malcolm's earlier assertion that the dinosaurs have somehow been breeding against the geneticists' design.

Meanwhile, the disgruntled chief programmer of Jurassic Park's controlling software, Dennis Nedry, attempts corporate espionage for Lewis Dodgson, a geneticist and agent of InGen's archrival, Biosyn. By activating a backdoor he wrote into the park's computer system, Nedry shuts down its security systems and steals frozen embryos for each of the park's fifteen species in an attempt to smuggle them to a contact waiting at an auxiliary dock at the eastern end of the park. However, during a sudden tropical storm, he exits his vehicle to get his bearings and is killed by a Dilophosaurus. Without Nedry to reactivate the park's security, the electrified fences remain off and all the dinosaurs escape. The park's adult Tyrannosaurus attacks the guests on tour, with a juvenile T. rex attacking and killing Ed Regis, the park's public relations manager. In the aftermath, Grant and the children become lost in the park. Malcolm is gravely injured during the incident, but is found by Gennaro and park game warden Robert Muldoon, spending the remainder of the novel slowly dying as – between lucid lectures and morphine-induced rants – he tries to help the others understand their predicament and survive.

The park's upper management — engineer and park supervisor John Arnold, biotechnologist Henry Wu, Muldoon, and Hammond — struggle to return power to the park, while the veterinarian, Dr. Harding, takes care of Malcolm. They manage to temporarily get the park largely back in order, restoring the computer system by shutting down and restarting the power and resetting the system. When trying to restore the park to working order, they fail to notice that the system has been running on auxiliary power since the restart; this power soon runs out, shutting the park down a second time. The park's intelligent and aggressive raptors escape their enclosure, and kill Wu and Arnold. Meanwhile, Grant and the children slowly make their way back to the Visitor Center by rafting down the jungle river, carrying news that several young raptors were on board the island's supply ship when it departed for the mainland. After the three return to the visitor's center, they are contacted by the others, who instruct Grant to switch on the park's generators. Tim is then able to reactivate the park's main power, allowing Gennaro to force the supply ship to return.

Gennaro orders that the island be destroyed, but Grant rejects his authority, claiming that they must first inspect the whole situation. Grant, Sattler, Muldoon, and Gennaro set out into the park to find the wild raptor nests and compare hatched eggs with the island's revised population tally, and return unscathed. Meanwhile, Hammond, taking a walk and contemplating building a new park improving on his previous mistakes, hears a T. rex roar and, startled, falls down a hill, where he is eaten by a pack of Procompsognathus.

With regard to the dinosaurs' breeding, it eventually transpires that using frog DNA to fill gaps in the dinosaurs' genetic code enabled a measure of dichogamy, in which some of the female animals changed into males in response to the same-sex environment. The computer tally failed to include newborn animals, having been programmed to stop counting once the assumed correct total number of animals had been found.

The survivors are rescued by the fictitious Costa Rican Air Force, where Grant reveals that the dinosaurs have been killing people. The Costa Rican Air Force then declare the island hazardous and unsafe, and proceed to raze the island with napalm. Survivors of the incident are indefinitely detained by the United States and Costa Rican governments at a hotel. Weeks later, Grant is visited by Dr. Martin Guitierrez, an American doctor who lives in Costa Rica. Guitierrez informs Grant that an unknown pack of animals has been migrating through the Costa Rican jungle, eating lysine-rich crops and chickens. He also informs Grant that none of them, with the possible exception of Tim and Lex, are going to leave any time soon.

Themes

Jurassic Park critiques the dystopian potentialities of science. There are Christian undertones in the skepticism of Ian Malcolm, though Christian terminology and imagery is never used. Malcolm is the conscience that reminds John Hammond of the sacrilegious path that has been taken. The final condition of the park is epitomized by the word "hell", which highlights the nature of Hammond's sacrilegious attempt.[10]

Michael Crichton's novel is another version of Mary Shelley's 1818 novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus tale where humanity creates without knowing. Henry Wu is unable to name the things that he creates, which alludes to Victor Frankenstein not knowing what to call his flawed imitation of God's creative powers. The immorality of these actions lead to human destruction, echoing Frankenstein.[11]

Similar to how his other novels represent science and technology as both hazardous and life-changing, Michael Crichton's novel highlights the hypocrisy and superiority complex of the scientific community that inspired John Hammond to re-create dinosaurs and treat them as commodities, which only lead to catastrophe. The similar fears of atomic power from the Cold War are adapted by Michael Crichton onto the anxieties evoked by genetic manipulation.[12]

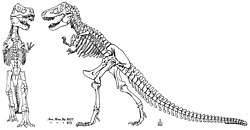

Dinosaurs in novel

The list is in alphabetical order

Reception

The book became a bestseller and Michael Crichton's signature novel. It also received largely favorable reviews by critics. In a review for The New York Times, Christopher Lehmann-Haupt described it as "a superior specimen of the [Frankenstein] myth" and "easily the best of Mr. Crichton's novels to date."[13] Writing for Entertainment Weekly, Gene Lyons held that the book was "hard to beat for sheer intellectual entertainment" largely because it was "[f]illed with diverting, up-to-date information in easily digestible form."[14] Both Lyons' Entertainment Weekly piece and Andrew Ferguson's review in the Los Angeles Times, however, criticized Crichton's characterization as heavy-handed and his characters as cliched. Ferguson further complained about Ian Malcolm's "dime-store philosophizing" and predicted that the film adaptation of the book would be "undoubtedly trashy." He conceded that the book's "only real virtue" was "its genuinely interesting discussions of dinosaurs, DNA research, paleontology and chaos theory."[15]

The novel became even more famous following the release of the 1993 film adaptation, which has grossed more than US$1 billion and spawned several sequels.[16]

In 1996 it was awarded the Secondary BILBY Award.[17]

See also

- The Cursed Earth, a Judge Dredd story line by Pat Mills in 2000 AD from 1978 that introduces the idea of a dinosaur theme park, with dinosaurs cloned from DNA

- Carnosaur, a 1984 novel with similar themes

- Westworld, Crichton's earlier 1973 film also about a malfunctioning theme park

References

- "Copyright information for Jurassic Park". United States Copyright Office. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- "JURASSIC PARK | Kirkus Reviews" – via www.kirkusreviews.com.

- Crichton, Michael (1997). Michael Crichton's Jurassic World. Knopf. ISBN 978-0375401077.

- "Michael Crichton's Jurassic world (information)". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2015-01-28.

- "Michael Crichton's Jurassic World: Jurassic Park, The Lost World". Barnes & Noble. Retrieved 2015-01-28.

- Crichton, Michael (2001). Michael Crichton on the Jurassic Park Phenomenon (DVD). Universal.

- "Return to Jurassic Park: Dawn of a New Era", Jurassic Park Blu-ray (2011)

- Website, M. C. "Jurassic Park".

- Means approximately "Clouded Island" or "Obscured Island" in Spanish.

- Gallardo-Terrano, Pedro (2000). "Rediscovering the Island as Utopian Locus: Michael Crichton's Jurassic Park". Retrieved 2018-08-02 – via Gale Academic OneFile. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Miracky, James (2004). "Replicating a Dinosaur: Authenticity Run Amok in the Theme Parking in Michael Crichton's Jurassic Park and Julian Barnes's England, England". Retrieved 2018-08-02 – via Gale Academic OneFile. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Geraghty, Lincoln (2018). "Jurassic Park". In Grant, Barry Keith (ed.). Books to Film: Cinematic Adaptations of Literary Works. 1. Retrieved 2018-08-02 – via Gale Academic OneFile.

- Lehmann-Haupt, Christopher (November 15, 1990). "Books of The Times; Of Dinosaurs Returned And Fractals Fractured". New York Times. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- Lyons, Gene (November 16, 1990). "Jurassic Park". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- Ferguson, Andrew (November 11, 1990). "The Thing From the Tar Pits : JURASSIC PARK By Michael Crichton (Alfred A. Knopf: $19.95; 413 pp.)". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- Jurassic Park (1993). Box Office Mojo (1993-09-24). Retrieved on 2013-09-17.

- "Previous Winners of the BILBY Awards: 1990 – 96" (PDF). www.cbcaqld.org. The Children's Book Council of Australia Queensland Branch. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 November 2015. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

Further reading

- DeSalle, Rob & Lindley, David (1997). The Science of Jurassic Park and The Lost World. Or How to Build a Dinosaur. New York: BasicBooks. ISBN 0-465-07379-4.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Jurassic Park (novel) |

- Isla Nublar novel map

- Official website

- Jurassic Park title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Jurassic Park at the official Michael Crichton website

| Awards | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Looking for Alibrandi |

Books I Love Best Yearly: Older Readers Award 1996 |

Succeeded by The Hobbit |