Reception of J. R. R. Tolkien

The works of J. R. R. Tolkien, especially The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, have become extremely popular, and have exerted considerable influence since their publication. A culture of fandom sprang up in the 1960s, leading to many popular votes in favour of the books, but acceptance by the establishment of literary criticism has been slower. Nevertheless, academic studies on Tolkien's works have been appearing at an increasing pace since the mid-1980s, prompting a measure of literary re-evaluation of his work.

Popular reception

Awards

In 1957, The Lord of the Rings was awarded the International Fantasy Award. The publication of the Ace Books and Ballantine paperbacks helped The Lord of the Rings become immensely popular in the 1960s. The book has remained so ever since, ranking as one of the most popular works of fiction of the twentieth century, judged by both sales and reader surveys.[1] In the 2003 "Big Read" survey conducted by the BBC, The Lord of the Rings was found to be the "Nation's best-loved book." In similar 2004 polls both Germany[2] and Australia[3] also found The Lord of the Rings to be their favourite book. In a 1999 poll of Amazon.com customers, The Lord of the Rings was judged to be their favourite "book of the millennium."[4]

Fandom

Tolkien fandom is an international, informal community of fans of Tolkien's Middle-earth works, including The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and The Silmarillion. The concept of Tolkien fandom as a specific type of fan subculture sprang up in the United States in the 1960s, in the context of the hippie movement, to the dismay of the author, who talked of "my deplorable cultus".[5]

Influence

The works of Tolkien have served as the inspiration to many painters, musicians, film-makers, writers, and game designers, to such an extent that Tolkien is sometimes seen as the "father" of the high fantasy genre.[6]

Literary reception

Early reviews of The Lord of the Rings were sharply divided between enthusiastic support and outright rejection.

Enthusiastic literary support

Some literary figures immediately welcomed the book's publication. W. H. Auden, a former pupil of Tolkien's and an admirer of his writings, regarded The Lord of the Rings as a "masterpiece", further stating that in some cases it outdid the achievement of John Milton's Paradise Lost.[7] Kenneth F. Slater wrote in Nebula Science Fiction, April 1955, "... if you don't read it, you have missed one of the finest books of its type ever to appear".[8][9] Michael Straight described it in The New Republic as "...one of the few works of genius in modern literature."[10] Iris Murdoch mentioned Middle-earth characters in her novels, and wrote to Tolkien saying she had been "utterly ... delighted, carried away, absorbed by The Lord of the Rings ... I wish I could say it in the fair Elven tongue."[11][12] Richard Hughes wrote that nothing like it had been attempted in English literature since Edmund Spenser's Faerie Queene, making it hard to compare, but that "For width of imagination it almost beggars parallel, and it is nearly as remarkable for its vividness and the narrative skill which carries the reader on, enthralled, for page after page."[13] Naomi Mitchison, too, was a strong and long-time supporter, corresponding with Tolkien about Lord of the Rings both before and after publication.[14][15]

A hostile literary establishment

Other literary reviewers rejected the work outright. In 1956, the literary critic Edmund Wilson wrote a review entitled "Oo, Those Awful Orcs!", calling Tolkien's work "juvenile trash", and saying "Dr. Tolkien has little skill at narrative and no instinct for literary form."[16]

In 1954, the Scottish poet Edwin Muir wrote in The Observer that "however one may look at it The Fellowship of the Ring is an extraordinary book",[17] but that although Tolkien "describes a tremendous conflict between good and evil ... his good people are consistently good, his evil figures immovably evil".[17] In 1955, Muir attacked The Return of the King, writing that "All the characters are boys masquerading as adult heroes ... and will never come to puberty ... Hardly one of them knows anything about women", causing Tolkien to complain angrily to his publisher.[18][19]

The fantasy author Michael Moorcock, in his 1978 essay, "Epic Pooh", compared Tolkien's work to Winnie-the-Pooh. He asserted, quoting from the third chapter of The Lord of the Rings, that its "predominant tone" was "the prose of the nursery-room .. a lullaby; it is meant to soothe and console."[20][21]

The hostility continued until the start of the 21st century. In 2001, The New York Times reviewer Judith Shulevitz criticized the "pedantry" of Tolkien's literary style, saying that he "formulated a high-minded belief in the importance of his mission as a literary preservationist, which turns out to be death to literature itself."[22] The same year, in the London Review of Books, Jenny Turner wrote that The Lord of the Rings provided "a closed space, finite and self-supporting, fixated on its own nostalgia, quietly running down";[23] the books were suitable for "vulnerable people. You can feel secure inside them, no matter what is going on in the nasty world outside. The merest weakling can be master of this cosy little universe. Even a silly furry little hobbit can see his dreams come true."[23] She cited the Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey's observation ("The hobbits ... have to be dug out ... of no fewer than five Homely Houses"[24]) that the quest repeats itself, the chase in the Shire ending with dinner at Farmer Maggot's, the trouble with Old Man Willow ending with hot baths and comfort at Tom Bombadil's, and again safety after adventures in Bree, Rivendell, and Lothlórien.[23] Turner commented that reading the book is to "find oneself gently rocked between bleakness and luxury, the sublime and the cosy. Scary, safe again. Scary, safe again. Scary, safe again."[23] In her view, this compulsive rhythm is what Sigmund Freud described in his Beyond the Pleasure Principle.[23] She asked whether, in his writing, Tolkien, whose father died when he was 3 and his mother when he was 12, was not "trying to recover his lost parents, his lost childhood, an impossibly prelapsarian sense of peace?"[23]

The critic Richard Jenkyns, writing in The New Republic in 2002, criticized a perceived lack of psychological depth. Both the characters and the work itself were, according to Jenkyns, "anemic, and lacking in fiber."[25] Also that year, the science-fiction author David Brin criticised the book in Salon as carefully-crafted and seductive, but backward-looking. He wrote that he had enjoyed it as a child as escapist fantasy, but that it clearly also reflected the decades of totalitarianism in the mid-20th century. Brin saw the change from feudalism to a free middle class as progress, and in his view Tolkien, like the Romantic poets, was opposed to that. As well as its being "a great tale", Brin saw good points in the work; Tolkien was, he wrote, self-critical, for example blaming the elves for trying to halt time by forging their Rings, while the Ringwraiths could be seen as cautionary figures of Greek hubris, men who reached too high, and fell.[26][27]

Even within Tolkien's literary group, The Inklings, reviews were mixed. Hugo Dyson complained loudly at its readings, and Christopher Tolkien records Dyson as "lying on the couch, and lolling and shouting and saying, 'Oh God, no more Elves.'"[28] However, another Inkling, C. S. Lewis, had very different feelings, writing, "here are beauties which pierce like swords or burn like cold iron." Despite these reviews and its lack of paperback printing until the 1960s, The Lord of the Rings initially sold well in hardback.[29]

Jared Lobdell, evaluating the hostile reception of Tolkien by the mainstream literary establishment in the 2006 J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia, noted that Wilson was "well known as an enemy of religion", of popular books, and "conservatism in any form".[18] Lobdell concluded that "no 'mainstream critic' appreciated The Lord of the Rings or indeed was in a position to write criticism on it — most being unsure what it was and why readers liked it."[18] He noted that Brian Aldiss, a critic of science fiction and He distinguished such "critics" from Tolkien scholarship, the study and analysis of Tolkien's themes, influences, and methods.[18]

Marxist criticism

Tolkien was strongly opposed to both Nazism and Communism; Hal Colebatch in the J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia notes that his views can be seen in the somewhat parodic "The Scouring of the Shire". Leftist critics have accordingly attacked Tolkien's social conservatism.[30] E. P. Thompson blames the cold warrior mentality on "too much early reading of The Lord of the Rings".[31] Other Marxist critics, however, have been more positive towards Tolkien. While criticizing the politics embedded in The Lord of the Rings,[32] China Miéville admires Tolkien's creative use of Norse mythology, tragedy, monsters, and subcreation, as well as his criticism of allegory.[33]

Tolkien research

Tolkien's fiction began to acquire respectability among academics only at the end of his life, with the publication of Paul H. Kocher's 1972 Master of Middle-Earth.[35] Since then, Tolkien's works have become the subject of a substantial body of academic research, both as fantasy and as an extended exercise in invented languages.[35] Richard C. West compiled an annotated checklist of Tolkien criticism in 1981.[36] Serious study began to reach the broader community with Shippey's 1982 The Road to Middle-earth and Verlyn Flieger's Splintered Light in 1983.[35] To borrow a phrase from Flieger, the academy had trouble "... taking seriously a subject which had, until he wrote, been dismissed as unworthy of attention."[37]

Alongside their analysis of Tolkien's work, Shippey and other scholars set about rebutting many of the literary critics' claims. For instance, Shippey pointed out that Muir's assertion that Tolkien's writing was non-adult, as the protagonists end with no pain, is not true of Frodo, who is permanently scarred and can no longer enjoy life in the Shire. Or again, he replies to Colin Manlove's attack on Tolkien's "overworked cadences" and "monotonous pitch" and the suggestion that the Ubi sunt section of the Old English poem The Wanderer is "real elegy" unlike anything in Tolkien, with the observation that Tolkien's Lament of the Rohirrim is a paraphrase of just that section;[38] other scholars have praised Tolkien's poem.[39] As a final example, he replies to the critic Mark Roberts's 1956 statement that The Lord of the Rings "is not moulded by some vision of things which is at the same time its raison d'etre";[40] he calls this one of the least perceptive comments ever made on Tolkien, stating that on the contrary the work "fits together ... on almost every level", with complex interlacement, a consistent ambiguity about the Ring and the nature of evil, and a consistent theory of the role of "chance" or "luck", all of which he explains in detail.[41]

In 1998, Daniel Timmons wrote in a dedicated issue of the Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts that scholars still disagreed about Tolkien's place in literature, but that those critical of it were a minority. He noted that Shippey had said that the "literary establishment" did not include Tolkien among the canon of academic texts, whereas Jane Chance "boldly declares that at last Tolkien 'is being studied as important in himself, as one of the world's greatest writers'".[35] Pressure to study Tolkien seriously came initially from fans rather than academics; the scholarly legitimacy of the field was still a subject of debate in 2015.[34][42]

The pace of scholarly publications on Tolkien increased dramatically in the early 2000s. The dedicated journal Tolkien Studies has been appearing since 2004. The open-access Journal of Tolkien Research has been published since 2014.[43] A bibliographic database of Tolkien criticism is maintained at Wheaton College.[44]

Literary re-evaluation

Brian Rosebury, a scholar of the humanities, considered why The Lord of the Rings has attracted so much literary hostility, and re-evaluated it as a literary work. He noted that many critics have stated that it is not a novel, and that some have proposed a medieval genre like "romance" or "epic". He cited Shippey's "more subtl[e]" suggestion that "Tolkien set himself to write a romance for an audience brought up on novels", noting that Tolkien did occasionally call the work a romance but usually called it a tale, a story, or a history.[45] Shippey argued that the work aims at Northrop Frye's "heroic romance" mode, only one level below "myth", but descending to "low mimesis" with the much less serious hobbits, who serve to deflect the modern reader's scepticism of the higher reaches of medieval-style romance.[46]

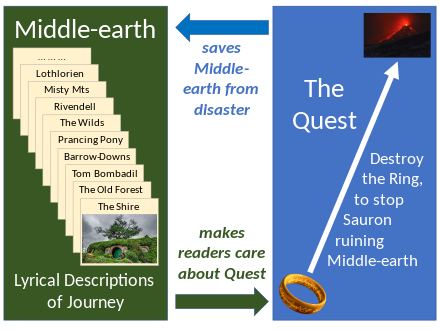

Rosebury noted that much of the work, especially Book 1, is largely descriptive rather than plot-based; it focuses mainly on Middle-earth itself, taking a journey through a series of tableaux – in the Shire, in the Old Forest, with Tom Bombadil, and so on. He states that "The circumstantial expansiveness of Middle-earth itself is central to the work's aesthetic power". Alongside this slow descriptiveness is the quest to destroy the Ring, a unifying plot line. The Ring needs to be destroyed to save Middle-earth itself from destruction or domination by Sauron. Hence, Rosebury argued, the book does have a single focus: Middle-earth itself. The work builds up Middle-earth as a place that readers come to love, shows that it is under dire threat, and – with the destruction of the Ring – provides the "eucatastrophe" for a happy ending. That makes the work "comedic" rather than tragic, in classical terms; but it also embodies the inevitability of loss, as the elves, hobbits and the rest decline and fade. Even the least novelistic parts of the work, the chronicles, narratives and essays of the appendices, help to built a consistent image of Middle-earth. The work is thus, Rosebury asserted, very tightly constructed, the expansiveness and plot fitting together exactly.[45]

In 2013, the fantasy author and humorist Terry Pratchett used a mountain theme to praise Tolkien, likening Tolkien to Mount Fuji, and writing that any other fantasy author "either has made a deliberate decision against the mountain, which is interesting in itself, or is in fact standing on [it]."[47]

In 2016, the British literary critic and poet Roz Kaveney reviewed five books about Tolkien in The Times Literary Supplement. She recorded that in 1991 she had said of The Lord of the Rings that it was worth "intelligent reading but not passionate attention",[48] and accepted that she had "underestimated the extent to which it would gain added popularity and cultural lustre from Peter Jackson's film adaptations".[48] As Pratchett had done, she used a mountain metaphor, alluding to Basil Bunting's poem about Ezra Pound's Cantos,[49] with the words "Tolkien's books have become Alps and we will wait in vain for them to crumble."[48] Kaveney called Tolkien's works "Thick Texts", books that are best read with some knowledge of his Middle-earth framework rather than as "single artworks". She accepted that he was a complicated figure, a scholar, a war survivor, a skilful writer of "light verse", a literary theorist, and a member of "a coterie of other influential thinkers". Further, she stated that he had much in common with accepted modernist writers like T. S. Eliot. She suggested that The Lord of the Rings is "a good, intelligent, influential and popular book", but perhaps not, as some of his "idolators" would have it, "a transcendent literary masterpiece".[48]

Reception of non-fiction works

Tolkien was an accomplished philologist, but he left a comparatively meagre output of academic publications. His works on philology which have received the most recognition are Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics, a 1936 lecture on the interpretation of the Old English poem Beowulf, and his identification of what he termed the "AB language", an early Middle English literary register of the West Midlands. Outside philology, his 1939 lecture On Fairy Stories is of some importance to the literary genres of fantasy or mythopoeia. His 1930 lecture A Secret Vice addressed artistic languages at a time when the topic was of very limited visibility compared to the utilitarian projects of auxiliary languages. His 1955 valedictory lecture English and Welsh expounds upon his philosophy of language, his notion of native language and his views on linguistic aesthetics (c.f. cellar door). Ross Smith published a monograph on Tolkien's philosophy of language.[50]

Notes

References

- Seiler, Andy (December 16, 2003). "'Rings' comes full circle". USA Today. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- Diver, Krysia (5 October 2004). "A lord for Germany". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Cooper, Callista (5 December 2005). "Epic trilogy tops favourite film poll". ABC News Online. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- O'Hehir, Andrew (4 June 2001). "The book of the century". Salon.com. Archived from the original on 10 June 2001. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Grossman, Lev (24 November 2002). "Feeding on Fantasy". Time magazine. Archived from the original on 8 June 2008.

- Mitchell, Christopher (12 April 2003). "J. R. R. Tolkien: Father of Modern Fantasy Literature" (streaming video). The Veritas Forum. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- Auden, W. H. (22 January 1956). "At the End of the Quest, Victory". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 February 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- "Ken Slater". Archived from the original on 30 October 2019. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- "Something to Read NSF 12". Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- "The Fantastic World of Professor Tolkien", Michael Straight, January 17, 1956, New republic

- Wood, Ralph C. (2015). Introduction: Tolkien among the Moderns. University of Notre Dame Press. pp. 1–6. doi:10.2307/j.ctvpj75hk. ISBN 978-0-268-15854-5.

What is less well known is that Murdoch had a deep and abiding affection for the fiction of J.R.R. Tolkien. She read and reread The Lord of the Rings. She refers to Tolkien's achievement in her philosophical works and alludes to his characters and his fiction in her own novels.

- Cowles, Gregory (9 June 2017). "Book Review: A Return to Middle-Earth, 44 Years After Tolkien's Death". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

Iris Murdoch, who sent Tolkien an admiring letter toward the end of his life. 'I have been meaning for a long time to write to you to say how utterly I have been delighted, carried away, absorbed by The Lord of the Rings', she wrote. 'I wish I could say it in the fair Elven tongue.'

- Wegierski, Mark (27 April 2013). "Middle Earth v. Duniverse – the different worlds of Tolkien and Herbert". The Quarterly Review. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

Something which has scarcely been attempted on this scale since Spenser's Faerie Queene, so one can't praise the book by comparisons – there’s nothing to compare it with. What can I say then?… For width of imagination it almost beggars parallel, and it is nearly as remarkable for its vividness and the narrative skill which carries the reader on, enthralled, for page after page.

- Mitchison, Naomi (18 September 1954). "Review: One Ring to Bind Them". New Statesman and Nation.

- Letters #122, #144, #154, #164, #176, #220 to Naomi Mitchison (dates in 1949, 1954-5, 1959)

- Wilson, Edmund (14 April 1956). "Oo, Those Awful Orcs! A review of The Fellowship of the Ring". The Nation. JRRVF. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- Muir, Edwin (22 August 1954). "Review: The Fellowship of the Ring". The Observer.

- Lobdell, Jared (2013) [2007]. "Criticism of Tolkien, Twentieth Century". In Michael D. C. Drout (ed.). J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 109–110. ISBN 978-0-415-96942-0.

- Letters, #177 to Rayner Unwin, 8 December 1955

- Michael Moorcock (1987). "RevolutionSF – Epic Pooh". RevolutionSF. Archived from the original on 24 March 2008. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Moorcock, Michael (1987). "5. "Epic Pooh"". Wizardry and Wild Romance: A study of epic fantasy. Victor Gollancz. p. 181. ISBN 0-575-04324-5.

- Shulevitz, Judith (22 April 2001). "Hobbits in Hollywood". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- Turner, Jenny (15 November 2001). "Reasons for Liking Tolkien". London Review of Books. 23 (22).

- Shippey, Tom (2001). J. R. R. Tolkien: Author of the Century. HarperCollins. p. 65. ISBN 978-0261-10401-3.

- Jenkyns, Richard (28 January 2002). "Bored of the Rings". The New Republic. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- Brin, David (17 December 2002). "J.R.R. Tolkien -- enemy of progress". Salon. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Brin, David (2008). The Lord of the Rings: J.R.R. Tolkien vs the Modern Age. Through Stranger Eyes: Reviews, Introductions, Tributes & Iconoclastic Essays. Nimble Books. part 1, "Dreading Tomorrow: Exploring our nightmares through literature", essay 3. ISBN 978-1-934840-39-9.

- Derek Bailey (Director) and Judi Dench (Narrator) (1992). A Film Portrait of J. R. R. Tolkien (Television documentary). Visual Corporation.

- Ebert, Roger (2006). Roger Ebert's Movie Yearbook 2007. Andrews McMeel Publishing. p. 897. ISBN 978-0-7407-6157-7.

- Colebatch, Hal G. P. (2013) [2007]. "Communism". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- Thompson, E. P. (24 January 1981). "America's Europe: A Hobbit among Gandalfs". Nation: 68–72.

- Mieville, China. "Tolkien - Middle Earth Meets Middle England". Socialist Review (January 2002).

- Mieville, China (15 June 2009). "There and Back Again: Five Reasons Tolkien Rocks". Omnivoracious.

- Schürer, Norbert (13 November 2015). "Tolkien Criticism Today". Los Angeles Review of Books. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Timmons, Daniel (1998). "J.R.R. Tolkien: The "Monstrous" in the Mirror". Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts. 9 (3 (35) The Tolkien Issue): 229–246. JSTOR 43308359.

- West, Richard C. (1981). Tolkien Criticism: An Annotated Checklist. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. ISBN 978-0873382564.

- Flieger, Verlyn (2002). Splintered Light: Logos and Language in Tolkien's World (2 ed.). Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-87338-744-6.

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). HarperCollins. pp. 175, 201-203 363-364. ISBN 978-0261102750.

- Higgins, Andrew (2014). "Tolkien's Poetry (2013), edited by Julian Eilmann and Allan Turner". Journal of Tolkien Research. 1 (1). Article 4.

- Roberts, Mark (1 October 1956). "Essays in Criticism". 6 (4): 450–459. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Shippey, Tom (2001). J. R. R. Tolkien: Author of the Century. HarperCollins. pp. 156-157 and passim. ISBN 978-0261-10401-3.

- Baugher, Luke; Hillman, Tom; Nardi, Dominic J. "Tolkien Criticism Unbound". Mythgard Institute. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- "Journal of Tolkien Research". Journal of Tolkien Research. Valparaiso University. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- "Tolkien Database". Wheaton College Dept. of English. Wheaton College. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- Rosebury, Brian (2003) [1992]. Tolkien : A Cultural Phenomenon. Palgrave. pp. 1–3, 12–13, 25–34, 41, 57. ISBN 978-1403-91263-3.

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). HarperCollins. pp. 237–249. ISBN 978-0261102750.

- Pratchett, Terry (2013). A Slip of the Keyboard : Collected Non-fiction. Doubleday. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-85752-122-4. OCLC 856191939.

- Kaveney, Roz (24 February 2016). "An English mythology". The Times Literary Supplement. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- Pound, Ezra. "On The Fly-Leaf Of Pound's Cantos". Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- Smith, Ross (2006). "Fitting Sense to Sound: Linguistic Aesthetics and Phonosemantics in the Work of J.R.R. Tolkien". Tolkien Studies. 3: 1–20.

.jpg)