Chinese fortune telling

Chinese fortune telling, better known as Suan ming (Chinese: 算命; pinyin: Suànmìng; lit.: 'fate calculating') has utilized many varying divination techniques throughout the dynastic periods. There are many methods still in practice in China, Taiwan and Hong Kong today. Over time, some of these concepts have moved into Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese culture under other names. For example, "Saju" in Korea is the same as the Chinese four pillar method.

History

The oldest accounts about practice of divination describe it as a measure for "solving doubts" (e.g. "Examination of doubts" 稽疑 part of the Great Plan zh:洪範). Two well known methods of divination included bǔ 卜 (on the tortoise shells) and shì 筮 (on the stalks of milfoil shī 蓍). Those methods were sanctioned by the royal practice since Shang and Zhou dynasties. Divination of the xiang 相 type (by appearance – of the human body parts, animals etc.), however, was sometimes criticized (the Xunzi, "Against divination"). Apparently, the later type was a part of the medical and veterinary practice, as well as a part necessary in match-making and marketing choices. A number of divination techniques developed around the astronomic observations and burial practices (see Feng shui, Guan Lu).

The dynastic chronicles preserve a number of reports when divination was manipulated to the end of achieving a political or personal goal.

Fortunetelling in the Ming Dynasty

A diverse culture of fortune telling that prevailed in the whole society came about during the Ming Dynasty.[1] This article is going to mainly explore the occupation of fortune-tellers in Ming, including their professional skills, contact with clients, and social impact.

Appearances

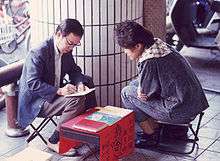

Some literary works in Ming time depicted the presence of various types of fortune-tellers. For instance, Story 13 in Stories to Caution the World by Feng Menglong illustrates the feature of a fortune-teller with “a bag on his back, a cap on his head, a black double-collar shirt with a silk waistband, a clean pair of shoes and socks on his feet, and a scroll of writing in his sleeves”.[2] Fortune tellers in Ming time developed their business in a variety of ways. Some of them would travel on foot, walking street by street and holding a sign describing their specialization. Book six in Stories to Caution the World portrays a fortune teller who walked alone on the road. By keeping a banner with the phrase “Divine Foresight,” the fortune teller could capture the client's attention.[2] Other fortune tellers in the country areas would also set up booths at places with a high population density, such as the city entrance and temples.[3]

Payments

Usually there is no strict contract on the payment to the fortune teller. Therefore, the fortune tellers sometimes need to deal with the clients about the fee.[4] The client could escape from paying the fortune teller, but he did not have a practical solution to that.[5] However, there are also cases where the clients would be willing to pay extra to the fortune-tellers when they were satisfied with the result.[6]

Methods

Physiognomy

General Practice

A physiognomer carefully examined one's body such as facial structure, complexion, body shape, and bones. A physiognomer made his calculations mainly based on the structure and shapes of these characteristics of one's body, where an auspicious future usually manifested on an ideal body feature.[7]

Techniques

The first and the most basic technique that a physiognomer would use was to take a look at the facial structure and the general body shape of the client. Size was one factor, whereby a physiognomer not only made a conclusion based on the size of a specific body part, but also the areas around it.[8] The other method a physiognomer would use was to compare the facial structure of the client to animals, which possessed distinctive symbolism and meanings. Through this connection, the physiognomer was able to make a general extrapolation of one's personality and career path. For instance, as mentioned in Shenxiang Quanbian, “the look of a tiger suggests intelligence, ambition, and the position of a general”.[9]

A physiognomer could reference Shenxiang Quanbian, which introduced six ways to read specific facial parts; for instance, one way to divide facial structure was to use to the geomantic theory by classifying each part of the face into specific mountains, rivers, and planets.[10] Furthermore, the other commonly used analysis was based on the concept of “yearly fortune”, where “it groups phases of life up to the age of ninety-nine under the twelve earthly branches, beginning in the general region of shen, near the top of the left ear, and ending at xu, on the left cheek”.[11] On this account, a physiognomer would calculate one's fate based on the specific facial feature which represents his or her fortune at that particular age.[12] “Shifu Meets a Friend at Tanque” by Feng Menglong tells a story between a physiognomer and Duke of Jin named Peidu at the beginning of the story, in which the physiognomer predicted Peidu's career path and wealth in few years based on the appearance of the region under Peidu's eyes.[13] In this story, the physiognomer was using the method of “yearly fortune”, and his object of the technique is the pattern of Peidu's facial feature.

Besides focusing on the structure and details of the face, another crucial technique for fortune tellers was to look at one's facial color to determine the potential success or failure a person might achieve. For example, a physiognomer might give warning to his client if he or she had a relatively dark face color. Based upon this fact, even though the way physiognomers judged a person's facial color was different from a doctor, he would still need to possess some basic medical knowledge to establish the ground for this calculation.[14]

“Five Elements”

Another important technique that a physiognomer would apply to tell the client's fate was to determine one's “five elements” by looking at his or her body shape.[15] Based on the writings of Shenxiang Quanbian, a physiognomer would pay attention to one's bones, eyes, shoulder, eyebrows, and other body features to determine one's own element, and then make the calculation of the client's fate based on their “five elements”.[16] For instance, a physiognomer would consider the client as a “water” person if “he had a round, heavy, and blackish appearance, with large eyes, thick eyebrows, hanging stomach, and erect shoulders.”[17] To read his client more deeply, he needed to go beyond the single quality of a specific element and to understand the complex relationship within the network of all five elements, and their various forms of manifestation in one's body.[18] Each of the elements can create a significant impact on the other, either negative or positive. The characteristic of the combination of any of these elements could differ from person to person, thus leading to a different result in the calculation of one's fate.[19] For example, “when a man of wood has some qualities of water he will enjoy honor and wealth, and will be above normal in scholarly undertakings”. [20]

Hand Reading

The other principal way in physiognomy is to determine one's fate through his or her hands, particularly palms. In general terms, a physiognomer first examines the shape and the skin of one's hand. For example, a physiognomer would consider those who have a large hand as fortunate people.[21] After looking at the shape of the hand, he will then carefully look at the pattern of his client's palm. A physiognomer would determine one's fate by reading the structure of the bumps and lines. A client's palm allowed the physiognomer to determine the client's health, wealth, and social status.[22]

Ziping Divination

Fortune-tellers in Ming time vastly adopted the method of Ziping divination, which was first introduced by a famous fate-calculator named Xu Ziping.[23]

Techniques

Ziping's method focused on the "ten stems" and "twelve branches" of a person's birth. This method is known for its application of “four pillars,” most commonly called “eight characters,” to calculate one's fate, and what shaped this method was the components of a person's year, month, day, and hour of birth.[24] Through combining the stem-branches of one's birth and their five elements, fortune tellers calculated the client's fate through finding the mutual relationship between these two.[25]

Geomancer

A geomancer examined the placement of homes and tombs. The principle was to seek a balance within the universe in order to secure a promising life or a particular event. Therefore, their object of technique is the house, tomb, time, and the cosmos.[26]

Techniques

One of the fundamental techniques for a geomancer was the use of a compass (luopan) as their tool for calculating location and time. A regular compass contained thirty-eight rings, which interconnect with “five elements”, “twelve branches”, “nine stars” and “ten stems”; therefore, a geomancer needs to figure out the particular symbol on the compass that can represent the nature of a location.[27] For example, “if the compass shows a certain spot to be associated with the planet Mars, and if the ‘agent’ wood is to the left of this point while ‘water’ is to the right of it, then the location will be inauspicious because water destroys fire and fire destroys wood.”[28]

Geomancers usually claimed expertise in “geology” because knowledge of geology enabled them to examine mountains, water, direction, and soil.[29]

- Face reading (面相) – This is the interpretation of facial features of the nose, eyes, mouth and other criteria within one's face and the conversion of those criteria into predictions for the future. This usually covers one phase of the client's life, and reveals the type of luck associated with a certain age range. A positions map also refers to different points on the face. This represents the person's luck at different ages. The upper region of the face represents youth, the middle region of the face represents middle age, and the lower region of the face represents old age.

- Palm reading (手相) – This analyzes the positioning of palm lines for love, personality, and other traits. It somewhat resembles Western palmistry in technique.

- Kau Cim (求籤) – This requires the shaking of a bamboo cylinder, which results in at least one modified incense stick leaving the cylinder. The Chinese characters inscribed on the stick are analyzed by an interpreter. The prediction is short range, as it covers one Chinese calendar year. In the West, this method has been popularized under the trade-name "Chi-Chi sticks."

- Zi wei dou shu (紫微斗數) – This procedure, sometimes loosely called (Chinese: 批命, pik meng) or Purple Star Astrology or Emperor/Purple (Star) Astrology, involves the client seeking an advisor with a mastery of the Chinese calendar. Astrology is used in combination with the Chinese constellations, four pillars of destiny and the five elements methods of divination. The end result is a translation of one's destiny path, an interpretation of a predetermined fate. The result of the details vary depending on the accuracy of the original four pillars information the client provides to the fortune-teller. This method can also verify unique events that have already happened in one's life.

- Bazi (八字) – This method is undoubtedly the most popular of Chinese Fortune Telling methods, and the most accessible one. It has many variants in practice the most simple one called: "Ziping Bazi" 子平八字, invented by Master Ziping. Generally it involves taking four components of time, the hour of birth, day, month and year. Each a pillar from the Sixty Jiazi and arranging them into Four Pillars. The Four Pillars are then analyzed against the Daymaster, the Heavenly Stem for the Day pillar. It is a form of Astrology as opposed to Fortune Telling or Divination, and tells one about his or her destiny in life, current situation and area for most successful occupation. Originally Bazi was read against the Year Earthly Branch, then focus shifted to the Month Pillar, then finally Master Xu Ziping refined and remade the system to use the Heavenly Stem of the Day Pillar as the emphasis and focus in reading. The practice for reading against the Year Branch is the origin of the popular Chinese Horoscopes for your Year of Birth.

- Wen Wang Gua or Man Wong Gua (文王卦) -,[30][31] also known as Liu Yao (六爻) or Wu Xing Yi (五行易) sometimes called Wu Xing Yi Shu – based on the Wu Xing.

- Mei Hua Yi Shu or Mui Fa Yik Sou (梅花易數) – Figuratively "Plum flower calculation", sometimes called Mei Hua Xin Yi. \Mui Fa Yik Sou, Zi wei dou shu, Tik Pan San Souzh:鉄版神數, North Pole calculation, South Pole calculation are five main calculation.[32]

- Qi Men Dun Jia (奇門遁甲) also known as Kei Mun Tun Kap, Dun Jia or just Dunjia/DunJia or sometimes Qi Men or Qimen/QiMen – Strange Doors and the Hidden Jia, The Hidden Jia escaping through the Strange Doors, Jia is given priority or importance. It is called Dun Jia because the objective of this Divination is to protect the Jia stem and move it to a safe place, wherever it may be found in the Qi Men Dun Jia chart or paipan. The second highest form of Chinese divination, according to Jack Sweeney. Used by Liu Bo Wen to help the Ming capture the throne.

- Yik Lam (易林)

- Yin Kam (演禽)

- Yin and Yang Bowl (陰陽杯) – based on Yin and yang

- Tik Pan San Sou (鐵板神數)

- Wong Kek Yin Sou (皇極易數)

- Seven Major and Four Minor Stars (七政四餘)

- Three Generation Life (三世書)

- Yin Kam Fa (演禽法)

- Chin Ting Sou (前定數)

- Leung Tou Kam (兩頭鉗) – Figuratively "dual headed suppress"

- Da Liu Ren (大六壬) also known as Liu Ren Shen Ke, or just Liu Ren, sometimes called Xiao Liu Ren – The Six Large Rens (Heavenly Stem), Ren in this case is given priority or importance. It is called Da Liu Ren because in the Sexegenary cycle there are Six Rens each with a different branch. The highest and most accurate form of Chinese divination, and after the Song Dynasty, the most popular in imperial China, based on texts found in the caves of Dun Huang. References to Da Liu Ren are found in dynastic histories and in the Romance of Three Kingdoms.

- Tai Yi Shen Shu (太乙神數) also known as Taiyi or TaiYi or Tai Yi – The Great Yi God Calculating, Calculating the God of the Great Yi, Yi is given priority or importance. Primarily used to launch wars or other major imperial activities, with a fortune telling component.

- Cheng Gu Ge (称骨歌) – Songs on Weighing Bones, fortune telling method by Yuan Tian Gang (袁天罡), involves adding up the "astrological weight" of the four time components and reading the total weight against a certain poem, thus revealing your life fate. Another method was by Zhang Zhong (Taoist).[33]

- Zhou Yi (周易) – also known as Yi Jing or I Ching, divination according to the book of changes. Methods include: Computer casting, Yarrow stalk casting, coin casting, paper casting, manual casting involves the yarrow stalks or coins.

- Yi Jing Numerology

- Date and Time Yi Jing

- Visual Yi Jing

- Huang Ji Jing Shi (皇極經世)- Fortune telling method based on the book by Shao Yong, the "Huang Ji Jing Shi"

- He Luo Li Shu – Fortune telling type numerology in accordance with the He Tu/Hetu/HeTu Diagram or the Yellow River Diagram

- Di Li Feng Shui – A geomancy based art of divination. Similar to Qi Men Dun Jia.

- Jiu Gong Ming Li (九宮命理) – Aka "9 Star Ki" or "Chi"/"Qi", also called "White and Purple Star Astrology"

There were a great variety of techniques fortune tellers were using, and those methods can be divided into six categories: astrology, calendars, bone-reading, five elements ("五行"), dream analysis, and analysis of physical objects.[34]

One interesting fact is that Chinese almanacs were refined significantly by Jesuits. Having witnessed a more accurate prediction of astronomical phenomena, the Ming government welcomed the Jesuits' modification of Chinese calendars and maintained the original way of predicting if a day was auspicious or inauspicious in the new calendars that were improved by the Jesuits.[35]

Sociology

In Chinese society, fortune telling is a respected and important part of social and business culture. Thus, fortune tellers often take on a role which is equivalent to management consultants and psychotherapists in Western society. As management consultants, they advise business people on business and investment decisions. Many major business decisions involve the input of fortune tellers. Their social role allows decision risks to be placed outside of the organization and provides a mechanism of quickly randomly deciding between several equally useful options. As psychotherapists, they help people discuss and resolve personal issues without the stigma of illness.

Path Into Occupation

The majority of the physiognomers recorded in the gazetteers are not identified.[36] Some of the fortune tellers were from poor families, and they entered the occupation in order to make a living. Many of them did not have the opportunity to study for the civil service examination.[37] Some blind people, disqualified from other occupations, would wander on the streets and practice physiognomy, particular the method of touching clients’ bones and listening to their voices.[36]

Many fortune tellers, in fact, were also in other occupations, and they practiced fortune tellings either for a secondary occupation. For instance, fortune tellers who were identified in the records were usually educated men from higher social classes, and some of them were even scholar-officials who played significant roles in government.[36] For instance, the Yuan family from the Ming Dynasty, who was the major contributor to the book of Shenxiang Quanbian, was also well-educated and participated in the central government.[38]

Others practiced it merely as a hobby, where they formed a fortune-telling community with other elite males.[37] Zhu Quan, one of the sons of Taizu, was fond of studying the knowledge of divination, and he frequently hung around with other literate males and discussed the skills of divination. He also wrote books about astrology, fate-calculation, and geomancy.[39]

Clients

A large portion of the clientele were those who were preparing for the civil service examination and hoping to obtain a position in the government. During the exam period, a large number of males and their families asked fortune tellers for their chances of success on the exam.[29] For instance, a student after taking the examination came to a fortuneteller named Cui Zijun, Cui predicted that he would get the top score, and when the results were released, the student was indeed in first place.[40] The more a fortune-teller could correctly predict the fate of clients, the better his reputation and credibility, and this would attract more clients wishing to know their results ahead of time. Sometimes a famous fortune-teller would sit at home, with a long line of clients out the door asking for a prediction.[41]

A separate group of fortune tellers relied on elite and imperial clients. For example, when Taizu went off to battle, he would bring a fortune teller named He Zhongli with him because he always made accurate predictions on the result of the battle. He Zhongli was later rewarded with a title in the Bureau of Astronomy.[37] Fortune tellers who built up a solid reputation could gain favors from the emperors and obtain upward social mobility.

In terms of the clients of geomancers, most of the household would go to geomancers when they needed to construct houses, choose the location for tombs, and hold events.[42] For instance, carpenters would be their clients to ask for the recommended layout of the gate and the home.[43]

In addition, many clients asked for advice on locating tombs to fulfill their duties of filial piety. People also strongly believed that through burying their elders’ into auspicious soil, they could preserve the prosperity of their families into the next generation.[29] Specifically, a geomancer needed to check if the location had “less wind but more water” so that the deceased would be able to peacefully live in another world and to bless the family. People tended to attribute the well-being of their family to the geomancer's professional abilities.[29]

Chinese fortune tellers talked to different classes of people. Some fortune tellers were doing their business on the streets and receiving very little payment (one coin). For instance, in Ling Mengzhu's story, the main character, Wen Ruoxu, paid one coin for the fortune teller's service.[44] On the other hand, albeit difficulty, fortune tellers could still enter the government and became officials as the craftsman in divining.[45] In this case, fortune tellers could serve the government and even the emperor. Yuan Gong, a fortune teller who was specialized in physiognomy, successfully predicted that Zhu Di would be the emperor of Ming and persuaded him to try to take over the throne.[46] Yuan benefited a lot from the early support of Zhu Di. Both Yuan Gong and his son were influential physiognomists who participated in national issues.[47]

Relations to Clients

Generally, a fortune-teller leads the conversation with the client by asking personal questions. During this process, the fortune-teller analyzes the client's choice of words and body language. He pays attention to not only the direct information that the client intends to reveal, but also the hidden facts about the client that he or she might not want to bring up in the conversation.[48] It was crucial for fortune tellers to seek a balance between showing off their knowledge and establishing credibility with their client.[49]

Social License

Fortune tellers had a social license because they were allowed by society to act in an unusual way; for example, a fortune teller was allowed to examine people's bodies and to make judgments based on them. Furthermore, some fortune tellers who practiced bone-touching were also allowed by society to touch the client's body, where other occupations did not have this license. Meanwhile, a fortune teller also had the social mandate to suggest to people what to do based on his occupational knowledge, which could have a significant impact on social order. During the reign of the Wanli Emperor, some greedy officials tried to exploit more mines in order to earn more profit, but this affected civilians’ living and caused chaos. On this account, a geomancer named Wu Peng stopped them from mining by telling them they would be unfortunate because they broke the balance of “Feng Shui”.[50] What's more, historical records show that one reason that Chengzu usurped the throne from his nephew was that a physiognomer named Yuan Gong predicted that he would become the emperor.[51]

Risks

Ending up as an official doesn't mean that those fortune tellers could all enjoy a wonderful life like Yuan's family. The Jesuits, who played an important role in reforming the calendars, took more responsibility after they were acknowledged by the Ming government. Since they became officials, it was their responsibility to divine when the auspicious days were for a specific task. Unfortunately, due to the popularity of divination in China, the Jesuits needed to do the calculation very often, and they did not fully understand this culture.[52] Furthermore, when fortune tellers became officials they also encountered attacks from other officials. One sardonic example was that the Jesuits, as specialists in astrology, were impeached by a Chinese scholar because of an inappropriate date they chose for a prince's funeral.[52]

Taboos

Among many fortune telling methods, one of them, Tianshi Dao ("天师道") explicitly limited its usage at their early period. Tianshi Dao's precepts warn Tianshi Dao Daoists that they should not divine for construction, using astrology, and divine for others, not even practice divining.[53] These precepts were possibly written in the third century, and the purpose of the precepts was to distinguish the Tianshidao Daoists from other Daoists who also knew techniques of divination. The reason behinds the precepts was that divination was not crucial for Tianshidao at the primary stage, and this technique just served to establish Tianshidao's ritual framework.[54]

Guilty knowledge and code

In Feng Menglong's story, the fortune tellers were unwilling to tell Pei Du that Pei had an unfortunate fate, and when he had to say, he asked for forgiveness beforehand and refused to receive any payment.[55] So, some fortune tellers knew that their prediction might ruin others' mood, but this was their job to tell the truth. To reach a compromise, the fortune teller in Feng's story decided to not take money from the poor customer. There is also another possibility that some fortune tellers would try to shock their clients by exaggerating the consequences of clients' luck, since Ge Hong, a famous Daoist, criticized that some fortune tellers wildly amplified the result they predicted [53]

Sometimes fortune telling also generates killings. When Yuan Gong told Zhu Di, the prince of Yan, that Zhu Di would be the emperor of Ming,[56] Yuan probably noticed that his words would help Zhu Di make his decision. Since the existing young emperor, Jianwen, would not just let his uncle take his throne, and after Zhu Di examined the trade-offs between waiting for punishment from Jianwen and fighting for the throne, Yuan's advice could be the last straw of Zhu Di's final decision. In 1399, Zhu Di declared the war and successfully defeated Jianwen in 1402, and the 4-year long war left many parts of northern China into ruins.[57] From this perspective, fortune telling could be dangerous.

A famous Chinese fortune-teller's maxim

Traditional Chinese: 一命二運三風水四積陰德五讀書 六名七相八敬神九交貴人十養生[58] Simplified Chinese:一命二运三风水四积阴德五读书 六名七相八敬神九交贵人十养生[59] Pinyin: yī mìng èr yùn sān fēngshuǐ sì jī yīndé wǔ dúshū, liù míng qī xiāng bā jìngshén jiǔ jiāo guìrén shí yǎngshēng. Jyutping: jat1 meng6 ji6 wan6 saam1 fung1 seoi2 sei3 zik1 jam1 dak1 ng5 duk6 syu1, ... English translation: one fate, two luck, three fengshui, four karma, five education/study, six name, seven face (may included every face on your body, mainly your head & palm), eight respect for the heaven(sky)/gods, nine relations with valuable / high rank men, ten keep living fit |

The above quote, relating to the "five components" of the good or ill fortune of any given individual, is culturally believed to have come from Su Shi of the Song dynasty.[60] As a maxim, it continues to remain popular in Chinese culture today. Actual interpretations of this quotation vary, as there is no classical text explaining what Su Shi really meant. Some claim that it signified that a person's destiny is under his or her own control as the "five components" of fortune are mathematically one more than the classical four pillars of destiny, which implies that individuals are in control of their futures on top of their natal "born" fates.[60] Other interpretations may suggest that the order in which the components are stated are important in determining the course of person's life: For example, education (the fifth fortune) is not useful if fate (the first fortune) does not put you in the proper place at the beginning of your life. Other interpretations may suggest that there is no inherent order to the sequence, but that they are just a list of the five components of a person's fortune.

An example of a regional ethnic proverb

"Many points lead to one point" is an ancient Chinese proverb, originating from the Jiangxi province. It refers to an ancient battle between the powers of good and evil, one of the founding schools of thought of the Chinese formation myth. The giants of evil used tweezers (approximate translation) to stab their opponents, whilst the dragon fairies had none and were losing. Wang won ju of the Good army then devised a cunning plan to divide the tweezers into two, wherein the giants vicariously stabbed themselves and Good triumphed. The moral of this story is that focusing on one task rather than two always brings greater results. Whilst not frequently used since ethnic tensions in the cultural revolution of 1966, it still has great meaning to a small minority in rural regions of Jiangxi.

See also

- Da Liu Ren

- Divination

- Fortune telling

- I Ching

- Qi Men Dun Jia

- Tie Ban Shen Shu

References

- Smith.J, Richard (1991). Fortune-tellers and Philosophers: Divination in Traditional Chinese Society. Westview Press. p. 45.

- Feng, Menglong, “Judge Bao Solves a Case Through a Ghost That Appeared Thrice” in Stories to Caution the World, translated by Shuhui Yang and Yunqin Yang (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2005), p199

- Gao Chang 高畅, “明清术士的工作内容与谋生之道--以安徽地方志为研究中心”(Warlocks’ Work and Way of Making a Living in the Ming and Qing Dynasties--Based on a Study of the Local History of Anhui Province), 黄山学院学报(Journal of Huangshan University) 18.4(August 2016): 39-45, p42

- Menglong, Feng, “Yuliang Writes Poems and Wins Recognitions” in Stories to Caution the World, translated by Shuhui Yang and Yunqin Yang (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2005), p 87

- Feng, “Yuliang Writes Poems and Wins Recognitions”, p87

- Feng, “Judge Bao Solves a Case Through a Ghost That Appeared Thrice”, p199

- Smith, Fortune-tellers and Philosophers: Divination in Traditional Chinese Society, p192

- Smith, p188

- Smith, p189

- William A. Lessa, “Chinese Body Divination: Its Forms, Affinities, and Functions” (Los Angeles: United World, 1968), p38

- Smith, p192

- Lessa, p52

- Menglong, Feng, “Shifu Meets a Friend at Tanque”, in Stories to Awaken the World: A Ming Dynasty Collection, translated by Shuhui Yang and Yunqin Yang (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000), p373

- Smith, p194

- Smith, p188

- Lessa, p38

- Lessa, p39

- Smith, p189

- Weipang, Chao, “The Chinese Science of Fate-Calculation” in Folklore Studies, Vol. 5 (1946), Nanzan University, p288

- Lessa, p40

- Smith, p196

- Lessa, p90

- Chao, “The Chinese Science of Fate-Calculation”, p 286

- Smith, p177

- Chao, p314

- Smith, p131

- Smith, p136

- Smith, p137

- Gao, p40

- Misterfengshui. "Misterfengshui Archived 2011-07-14 at the Wayback Machine." Chinese metaphysics 網上香港風水學家黃頁. Retrieved on 2008-01-05.

- Fengshui magazine. "Fengshui-magazine." Chinese metaphysics 網上香港風水學家黃頁. Retrieved on 2008-01-05.

- 【五大神數】【五大神數之邵子神數】

- "鉄冠道眞人称命術--- 中國根源藝術網". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2013-07-27.

- Smith, Richard J. “‘Knowing Fate’: Divination in Late Imperial China.” Journal of Chinese Studies, vol. 3, no. 2, 1986, pp. 155. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/44288022.

- Smith, Richard J. “‘Knowing Fate’: Divination in Late Imperial China.” pp. 160–161.

- Smith, p205

- Gao, p42

- Kohn, “A Textbook on Physiognomy: the Tradition of ‘Shenxiang Quanbian”, p230

- Yuan Shushan袁树珊, Biography of Chinese Diviners,中国历代卜人传, Shanghai 1948, p434

- Yuan, p65

- Yuan, p356

- Smith, p184

- Ruitenbeek, Klaas, Carpentry and Building in Late Imperial China: A Study of the Fifteenth-Century Carpenter’s Manual Lu Ban Jing(Leiden: New York: E. J. Brill, 1993), pp278-280

- LING Mengzhu (1580-1644), "The Tangerines and the Tortoise Shell," from his Slapping the Table in Amazement (1628)." Translated in Lazy Dragon: Chinese Stories from the Ming Dynasty, by Yang Xianyi and Gladys Yang, (Hong Kong: NJoint Publishing Xo., 1981), pp.241, @Joint Publishing Co. Hong Kong Branch 1981. All rights Reserved.

- Hendrischke, Barbara. “DIVINATION IN THE TAIPING JING.” Monumenta Serica, vol. 57, 2009, pp. 39. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40727620.

- Kohn, Livia. “A Textbook of Physiognomy: The Tradition of the ‘Shenxiang Quanbian.’” Asian Folklore Studies, vol. 45, no. 2, 1986, pp. 230–231. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1178619.

- Kohn, Livia. “A Textbook of Physiognomy: The Tradition of the ‘Shenxiang Quanbian.’” pp. 231.

- Smith, p208

- Smith, p207

- Gao, p41

- Chen Baoliang, 陈宝良, ”明代社会生活史” (Social Life and Custom in the Ming Period), 中国社会科学出版社 (Beijing: China Social Science Press), (March 2004).

- Smith, Richard J. “‘Knowing Fate’: Divination in Late Imperial China.” pp. 161.

- Hendrischke, Barbara. “DIVINATION IN THE TAIPING JING.” pp. 36.

- Hendrischke, Barbara. “DIVINATION IN THE TAIPING JING.” pp. 37.

- Feng Menglong(1574-1646), "Shi Fu Meets a Friend at Tanque" in Stories to Awaken the World: A Ming Dynasty Collection, transl, Yang & Yang (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2009), pp. 373, 952. Permission to reprint by U of Washington Press.

- Kohn, Livia. “A Textbook of Physiognomy: The Tradition of the ‘Shenxiang Quanbian.’” pp. 230–231.

- John W. Dardess, Ming China 1368-1644:A Concise History of a Resilient Empire. (Lanham, MD:Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2012), p34

- 一命、二運、三風水、四積陰德、五讀書..的來源與探討~台灣六愚

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-02-23. Retrieved 2014-07-28.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Fsrcenter. "Fsrcenter." Su Dong Po's misinterpreted saying. Retrieved on 2008-01-05.

- Smith, Richard J. Fortune-tellers and Philosophers: Divination in Traditional Chinese Society. Boulder, Colorado and Oxford England: Westview Press, 1991.

- http://www.lz333.com/News_show.asp?Newsid=274