Stilt house

Stilt houses are houses raised on stilts over the surface of the soil or a body of water. Stilt houses are built primarily as a protection against flooding;[1] they also keep out vermin.[2] The shady space under the house can be used for work or storage.[3]

History

In the Neolithic and the Bronze Age, stilt-house settlements were common in the Alpine and Pianura Padana (Terramare) regions.[4] Remains have been found at the Ljubljana Marshes in Slovenia and at the Mondsee and Attersee lakes in Upper Austria, for example. Early archaeologists like Ferdinand Keller thought they formed artificial islands, much like the Irish and Scottish crannogs, but today it is clear that the majority of settlements were located on the shores of lakes and were only inundated later on.[5] Reconstructed stilt houses are shown in open-air museums in Unteruhldingen and Zürich (Pfahlbauland). In June 2011, the prehistoric pile dwellings in six Alpine states were designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites. A single Scandinavian pile dwelling, the Alvastra stilt houses, has been excavated in Sweden. Herodotus has described in his Histories the dwellings of the "lake-dwellers" in Paeonia and how those were constructed.[6]

Arctic

Houses where permafrost is present, in the Arctic, are built on stilts to keep permafrost under them from melting. Permafrost can be up to 70% water. While frozen, it provides a stable foundation. However, if heat radiating from the bottom of a home melts the permafrost, the home goes out of level and starts sinking into the ground. Other means of keeping the permafrost from melting are available, but raising the home off the ground on stilts is one of the most effective ways.

Southern hemisphere

According to archeological evidence, stilt-house settlements were an architectural norm in the Caroline Islands and Micronesia, and these are still present in Oceania.[7] Today, stilt houses are also still common in parts of the Mosquito Coast in northeastern Nicaragua, northern Brazil, South East Asia, Papua New Guinea, and West Africa.[8] Stilted granaries are also a common feature in West Africa, e.g., in the Malinke language regions of Mali and Guinea.

Western hemisphere

In the Alps, similar buildings, known as raccards, are still in use as granaries. In England, granaries are placed on staddle stones, similar to stilts, to prevent mice and rats getting to the grain. Stilt houses are also common in the western hemisphere, and are an example of multiple discovery. They were built by Amerindians in pre-Columbian times. Palafitos are especially widespread along the banks of the tropical river valleys of South America, notably the Amazon and Orinoco river systems. Stilt houses were such a prevalent feature along the shores of Lake Maracaibo that Amerigo Vespucci was inspired to name the region "Venezuela" (little Venice). As the costs of hurricane damage increase, more and more houses along the Gulf Coast are being built as or converted to stilt houses.[9]

Types

- Diaojiaolou – Stilt houses in southern China.

- Heliotrope – A concept house designed by Rolf Disch with a single stilt, optimized for harnessing solar power.

- Kelong – Built primarily for fishing, but often doubling up as offshore dwellings in the following countries: Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore.

- Bahay Kubo – The traditional house type prevalent in the Philippines.

- Palafito – Found throughout South America since Pre-Columbian times. In the late 19th century, numerous palafitos were built in Chilean cities such as Castro, Chonchi, and other towns in the Chiloé Archipelago, and are now considered a typical element of Chilotan architecture.

- Pang uk – A special kind of house found in Tai O, Lantau, Hong Kong, mainly built by Tankas.

- Papua New Guinea stilt house – A kind of stilt house constructed by Motuans, commonly found in the southern coastal area of PNG.

- Queenslander – Stilt house common in Queensland and northern New South Wales, Australia.

- Sang Ghar - A type of stilt house built in Assam state of India. It is mainly found in flood-prone areas of the Brahmaputra river valley.

- Thai stilt house – A kind of house often built on freshwater, e.g., a lotus pond.

- Vietnamese stilt house – Similar to the Thai ones, except having a front door with a smaller height for religious reasons.

Gallery

Lacustrine Village found in Lake Zurich, Switzerland

Lacustrine Village found in Lake Zurich, Switzerland Rumoh Aceh, Acehnese traditional house

Rumoh Aceh, Acehnese traditional house Stilt houses in Cempa, located in the Lingga Islands of Indonesia

Stilt houses in Cempa, located in the Lingga Islands of Indonesia A stilt house in Attapeu Province, southern Laos

A stilt house in Attapeu Province, southern Laos- Stilt houses along Puget Sound in Fragaria, Washington, United States

A rural stilt house in Cambodia

A rural stilt house in Cambodia Bajau stilt houses over the sea in the Philippines

Bajau stilt houses over the sea in the Philippines A stilt house in Southern Thailand

A stilt house in Southern Thailand An African home reconstructed in Germany

An African home reconstructed in Germany A bridge between stilt houses (palafito) in Colombia, in Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta

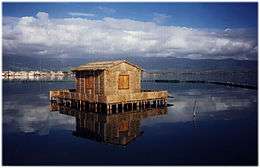

A bridge between stilt houses (palafito) in Colombia, in Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta Traditional stilt house in the Missolonghi Lagoon, Western Greece

Traditional stilt house in the Missolonghi Lagoon, Western Greece- Stilt houses on Tonlé Sap Lake, Cambodia

Vacation resort in the Maldives

Vacation resort in the Maldives The biggest stilt house in Vietnam

The biggest stilt house in Vietnam

See also

- Pfahlbaumuseum Unteruhldingen – an English-language article about the stilt house museum in Unteruhldingen, Germany

- Pit-house

- Post in ground

- Prehistoric pile dwellings around the Alps

- Rumah Melayu

- Stiltsville

- Treehouse

- Venice

- Wood pilings

References

- Bush, David M. (June 2004). Living with Florida's Atlantic beaches: Coastal hazards from Amelia Island to Key West. Duke University Press. pp. 263–264. ISBN 978-0-8223-3289-3. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- Our Experts. Our Living World 5. Ratna Sagar. p. 63. ISBN 978-81-8332-295-9. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- Cambodian Heritage Camp yearbook.

- Alan W. Ertl (15 August 2008). Toward an Understanding of Europe: A Political Economic Précis of Continental Integration. Universal-Publishers. p. 308. ISBN 978-1-59942-983-0. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- Francesco Menotti (2004). Living on the lake in prehistoric Europe: 150 years of lake-dwelling research. Psychology Press. pp. 22–25. ISBN 978-0-415-31720-7. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- Herodotus, Histories, 5.16

- Paul Rainbird (14 June 2004). The archaeology of Micronesia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 92–98. ISBN 978-0-521-65630-6. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- Dindy Robinson (15 August 1996). World cultures through art activities. Libraries Unlimited. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-1-56308-271-9. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- "Fortified Home Design Pioneered on the Texas Gulf Coast". Texasgulfcoastonline.com. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stilt houses. |