Steenbok

The steenbok (Raphicerus campestris) is a common small antelope of southern and eastern Africa. It is sometimes known as the steinbuck or steinbok.

| Steenbok | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

.jpg) | |

| Male and female in Etosha N. P. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Bovidae |

| Subfamily: | Antilopinae |

| Genus: | Raphicerus |

| Species: | R. campestris |

| Binomial name | |

| Raphicerus campestris Thunberg, 1811 | |

| |

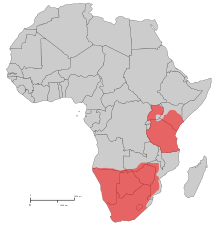

| Distribution based on 1970s data.[2] | |

Description

Steenbok resemble small Oribi, standing 45–60 cm (16"–24") at the shoulder. Their pelage (coat) is any shade from fawn to rufous, typically rather orange. The underside, including chin and throat, is white, as is the ring around the eye. Ears are large with "finger-marks" on the inside. Males have straight, smooth, parallel horns 7–19 cm long (see image left). There is a black crescent-shape between the ears, a long black bridge to the glossy black nose, and a black circular scent-gland in front of the eye. The tail is not usually visible, being only 4–6 cm long.

Distribution

There are two distinct clusters in steenbok distribution. In East Africa, it occurs in central and southern Kenya and northern Tanzania. It was formerly widespread in Uganda,[2] but is now almost certainly extinct there. In Southern Africa, it occurs in Angola, Namibia, South Africa, Eswatini, Botswana, Mozambique, Zambia, Zimbabwe and probably Lesotho.

Habitat

Steenbok live in a variety of habitats from semi-desert, such as the edge of the Kalahari Desert and Etosha National Park, to open woodland and thickets, including open plains, stony savannah, and Acacia–grassland mosaics. They are said to favour unstable or transitional habitats.[4] At least in the central part of Kruger National Park, South Africa, Steenbok show a distinct preference for Acacia tortilis savannah throughout the year, with no tendency to migrate to moister areas during the dry season (unlike many larger African savannah ungulates, including species sympatric with Steenbok in the wet season).[5]

Population density is typically 0.3–1.0 individuals per square kilometre, reaching 4 per km2 in optimal habitats.[6]

Diet

Steenbok typically browse on low-level vegetation (they cannot reach above 0.9 m[7]), but are also adept at scraping up roots and tubers. In central Kruger National Park, Steenbok show a distinct preference for forbs, and then woody plants (especially Flueggea virosa) when few forbs are available.[5] They will also take fruits and only very rarely graze on grass.[5] They are almost entirely independent of drinking water, gaining the moisture they need from their food.

Behaviour

Steenbok are active during the day and the night; however, during hotter periods, they rest under shade during the heat of the day. The time spent feeding at night increases in the dry season.[8] While resting, they may be busy grooming, ruminating or taking brief spells of sleep.[9]

Anti-predator

At the first sign of trouble, steenbok typically lie low in the vegetation. If a predator or perceived threat comes closer, a steenbok will leap away and follow a zigzag route to try to shake off the pursuer. Escaping steenbok frequently stop to look back, and flight is alternated with prostration during extended pursuit. They are known to take refuge in the burrows of Aardvarks. Known predators include Southern African wildcat, caracal, jackals, leopard, martial eagle and pythons.

Breeding

Steenbok are typically solitary, except for when a pair come together to mate. However, it has been suggested[4] that pairs occupy consistent territories while living independently, staying in contact through scent markings, so that they know where their mate is most of the time. Scent marking is primarily through dung middens. Territories range from 4 hectares to one square kilometre. The male is aggressive during the female's oestrus, engaging in "bluff-and-bluster" type displays with rival males—prolonged contests invariably involve well-matched individuals, usually in their prime.[9]

Breeding occurs throughout the year, although more fawns are born November to December in the southern spring–summer; some females may breed twice a year. Gestation period is about 170 days, and usually a single precocious fawn is produced. The fawn is kept hidden in vegetation for 2 weeks, but they suckle for 3 months. Females become sexually mature at 6–8 months and males at 9 months.

Steenbok are known to live for 7 years or more.

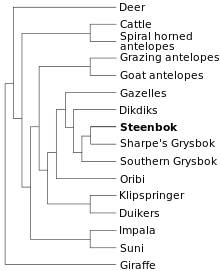

Taxonomy

Two subspecies are recognized: R. c. campestris in Southern Africa and R. c. naumanni of East Africa; although MSW3 also recognizes capricornis and kelleni.[10] Up to 24 subspecies have been described from Southern Africa, distinguished on such features as coat colour.

Gallery

Female in South Africa

Female in South Africa_male.jpg) Backlit male showing white fur in ears, Tswalu Kalahari Res.

Backlit male showing white fur in ears, Tswalu Kalahari Res._running_composite.jpg) Female running in Damaraland, Namibia

Female running in Damaraland, Namibia

References

- IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group (2008). "Raphicerus campestris". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. Retrieved 15 November 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Williams, John G. 1967. A Field Guide to the National Parks of East Africa. Collins, London. (ISBN 0-00-219294-2)

- Matthee, Conrad A.; Scott K. Davis (2001). "Molecular Insights into the Evolution of the Family Bovidae: A Nuclear DNA Perspective" (PDF). Molecular Biology and Evolution. Society for Molecular Biology and Evolution. 18 (7): 1220–1230. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003908. PMID 11420362. Retrieved 2007-06-17.

- Kingdon, Jonathan. 1997. The Kingdon Field Guide to African Mammals. Academic Press, San Diego & London. Pp. 387–388. (ISBN 0-12-408355-2)

- Du Toit, Johan T (1993). "The feeding ecology of a very small ruminant, the steenbok (Raphicerus campestris)". African Journal of Ecology. 31: 35–48. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1993.tb00516.x.

- Kleiman, David G. et al., Eds. 2003. Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia, 2nd edn. Vol. 16: Mammals V. Gale Cengage Learning. Pp. 59–72.

- Du Toit, J.T. (1990). "Feeding-height stratification among African browsing ruminants". African Journal of Ecology. 28: 55–61. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1990.tb01136.x.

- Smithers, Reay H.N. (2000). Apps, Peter (ed.). Smithers' Mammals of Southern Africa. A field guide. Cape Town: Struik publishers. p. 197. ISBN 1868725502.

- Cohen, Michael. 1976. The Steenbok: A neglected species. Custos (April 1976): 23–26.

- Grubb, P. (2005). "Order Artiodactyla". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 688. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Raphicerus campestris. |