Tskhinvali

Tskhinvali (Georgian: ცხინვალი [t͡sxinvali] (![]()

Tskhinvali | |

|---|---|

Tskhinvali | |

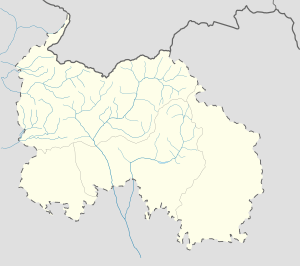

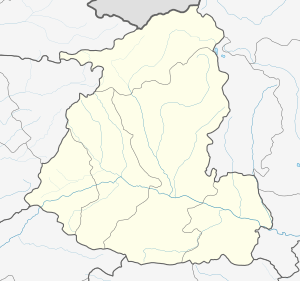

Tskhinvali Location of Tskhinvali  Tskhinvali Tskhinvali (Shida Kartli)  Tskhinvali Tskhinvali (Georgia) | |

| Coordinates: 42°13′35″N 43°58′10″E | |

| Country | |

| Mkhare | Shida Kartli |

| Established | 1398 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 7.4 km2 (2.9 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 860 m (2,820 ft) |

| Population (1 January 2019) | |

| • Total | 32,180[2] |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (Moscow time) |

| Climate | Dfb |

Name

The name of Tskhinvali is derived from the Old Georgian Krtskhinvali (Georgian: ქრცხინვალი), from earlier Krtskhilvani (Georgian: ქრცხილვანი), literally meaning "the land of hornbeams",[3][4] which is the historical name of the city.[5] See ცხინვალი for more.

From 1934 to 1961, the city was named Staliniri (Georgian: სტალინირი, Ossetian: Сталинир), which was compilation of Joseph Stalin's surname with Ossetian word "Ir" which means Ossetia. Modern Ossetians call the city Tskhinval (leaving off the final "i", which is a nominative case ending in Georgian); the other Ossetian name of the city is Chreba (Ossetian: Чъреба) which is only spread as a colloquial word.[6]

History

The area around the present-day Tskhinvali was first populated back in the Bronze Age. The unearthed settlements and archaeological artifacts from that time are unique in that they reflect influences from both Iberian (east Georgia) and Colchian (west Georgia) cultures with possible Sarmatian elements.

Tskhinvali was first chronicled by Georgian sources in 1398 as a village in Kartli (central Georgia) though a later account credits the 3rd century AD Georgian king Aspacures II of Iberia with its foundation as a fortress. By the early 18th century, Tskhinvali was a small "royal town" populated chiefly by monastic serfs. Tskhinvali was annexed to the Russian Empire along with the rest of eastern Georgia in 1801. Located on a trade route which linked North Caucasus to Tbilisi and Gori, Tskhinvali gradually developed into a commercial town with a mixed Jewish, Georgian, Armenian and Ossetian population. In 1917, it had 600 houses with 38.4% Georgian Jews, 34.4% Georgians, 17.7% Armenians and 8.8% Ossetians.[7]

The town saw clashes between Georgian People's Guard and pro-Bolshevik Ossetian peasants during the 1918-20 period, when Georgia gained brief independence from Russia. Soviet rule was established by the invading Red Army in March 1921, and a year later, in 1922, Tskhinvali was made a capital of the South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast within the Georgian SSR. Subsequently, the town became largely Ossetian due to intense urbanisation and Soviet Korenizatsiya ("nativization") policy which induced an inflow of the Ossetians from the nearby rural areas into Tskhinvali. It was essentially an industrial centre, with lumber mills and manufacturing plants, and had also several cultural and educational institutions such as a venerated Pedagogical Institute (currently Tskhinvali State University) and a drama theatre. According to the last Soviet census (in 1989), Tskhinvali had a population of 42,934, and according to the census of Republic of South Ossetia in 2015, the population was 30,432 people.

During the acute phase of the Georgian-Ossetian conflict, Tskhinvali was a scene of ethnic tensions and ensuing armed confrontation between Georgian and Ossetian forces. The 1992 Sochi ceasefire accord left Tskhinvali in the hands of Ossetians.

Russo-Georgian War

In late June, 2008 Russian military expert Pavel Felgenhauer predicted that Vladimir Putin would start a war against Georgia in Abkhazia and South Ossetia supposedly in August.[11][12] The Kavkaz Center reported in early July that Chechen separatists had intelligence data that Russia was preparing a military operation against Georgia in August–September 2008 which mainly aimed to expel Georgian forces from the Kodori Gorge; this would be followed by the expulsion of Georgian military and population from South Ossetia.[13]

At 8:00 am on 1 August, a Georgian police vehicle was blown up by an improvised explosive device on the road near Tskhinvali, injuring five Georgian policemen. In response, Georgian snipers assaulted some of the South Ossetian border checkpoints, killing four Ossetians and injuring seven.[14]

Ossetian separatists began intensively shelling Georgian villages on 1 August, with a sporadic response from Georgian peacekeepers and other troops in the region.[15][16][17][18] During the night of 1/2 August, grenades and mortar fire were exchanged. The number of Ossetian casualties rose to six and the number of injured to fifteen, including several civilians; the Georgian casualties were six injured civilians and one injured policeman.[14]

The Russian deputy defence minister, Nikolay Pankov, had a secret meeting with the separatist authorities in Tskhinvali on 3 August.[19] An evacuation of Ossetian women and children to Russia began on the same day.[11] According to researcher Andrey Illarionov, the South Ossetian separatists evacuated more than 20,000 civilians, which represented more than 90 percent of the civilian population of the future combat zone.[20]

On 4 August, South Ossetian president Eduard Kokoity said that about 300 volunteers had arrived from North Ossetia to help fight the Georgians and thousands more were expected from the North Caucasus.[21] On 5 August, Georgian authorities organised a tour for journalists and diplomats to demonstrate the damage supposedly caused by separatists. That day, Russian Ambassador-at-Large Yuri Popov declared that his country would intervene on the side of South Ossetia.[22] The destruction of the village of Nuli was ordered by South Ossetian interior minister Mindzaev.[23] About 50 Russian journalists had arrived in Tskhnivali. They were waiting for "something to happen".[11] A pro-government Russian newspaper reported on 6 August: "Don Cossacks prepare to fight in South Ossetia".[24][25]

Mortar and artillery exchange between the South Ossetian and Georgian forces erupted in the afternoon of 6 August along almost the entire line of contact, which lasted until the dawn of 7 August. Exchanges resumed following a brief gap in the morning.[26][23] At 14:00 on 7 August, two Georgian peacekeepers were killed in Avnevi as a result of Ossetian shelling.[27][28] At about 14:30, Georgian tanks, 122 mm howitzers and 203 mm self-propelled artillery began heading towards South Ossetia to dissuade separatists from additional attacks.[29] During the afternoon, OSCE monitors recorded Georgian military traffic, including artillery, on roads near Gori.[27] In the afternoon, Georgian personnel left the Joint Peacekeeping Force headquarters in Tskhinvali.[30]

Tskhinvali was shelled by the Georgian government on 8 August 2008 with BM-21 "Grad" mobile artillery rocket systems in an attempt to regain control over the breakaway republic of South Ossetia. After the bombings, the Georgian army invaded the city in an attempt to gain control on it. The Russian army responded on the following day by moving its own forces into the city and counterattacking the Georgian army. On 10 August Georgian forces pulled out of Tskhinvali, which was captured by the Russian army after intense fighting.

A considerable part of the population of South Ossetia (at least, 30,000 out of 70,000) fled into North Ossetia–Alania prior or immediately after the start of the war.[31] However, many civilians were killed during the shelling and the following Battle of Tskhinvali (162 civilian deaths were documented by the Russian team of investigators[32] and 365 - by the South Ossetian authorities[33]). The town was heavily damaged during the battle. The Jewish Quarter — one of the town's unique neighbourhoods was also reported to be destroyed.[34] Andrey Illarionov visited the town in October 2008, and reported that Jewish Quarter indeed was in ruins, though he observed that the ruins were overgrown with shrubs and trees, which indicates that the destruction took place during the 1991–1992 South Ossetia War.[35] However, Mark Ames, who was covering the last war for The Nation, stated that Tskhinvali's main residential district, nicknamed Shanghai because of its population density (it's where most of the city's high-rise apartment blocks are located), and the old Jewish Quarter, were completely destroyed.[36]

Geography

Climate

Located in the Caucasus, at 860 metres (2,820 ft) above sea level, Tskhinvali has a humid continental climate (Köppen: Dfb), with an average annual precipitation of 805 millimetres (31.7 in). Summers are mild and winters are cold, with snowfalls.

| Climate data for Tskhinvali | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 1.9 (35.4) |

3.3 (37.9) |

7.8 (46.0) |

14.2 (57.6) |

19.5 (67.1) |

22.8 (73.0) |

25.2 (77.4) |

25.4 (77.7) |

21.2 (70.2) |

15.8 (60.4) |

8.7 (47.7) |

4.0 (39.2) |

14.2 (57.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −2.6 (27.3) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

2.8 (37.0) |

8.1 (46.6) |

13.3 (55.9) |

16.6 (61.9) |

19.1 (66.4) |

19.2 (66.6) |

14.9 (58.8) |

9.9 (49.8) |

4.1 (39.4) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

8.6 (47.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −7.1 (19.2) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

2.0 (35.6) |

7.2 (45.0) |

10.4 (50.7) |

13.1 (55.6) |

13.0 (55.4) |

8.6 (47.5) |

4.1 (39.4) |

0.5 (32.9) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

3.2 (37.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 46 (1.8) |

46 (1.8) |

52 (2.0) |

74 (2.9) |

97 (3.8) |

97 (3.8) |

75 (3.0) |

66 (2.6) |

60 (2.4) |

68 (2.7) |

65 (2.6) |

59 (2.3) |

805 (31.7) |

| Source: Climate-data.org[37] | |||||||||||||

Present

Currently, Tskhinvali functions as the capital of South Ossetia. Before the 2008 war it had a population of approximately 30,000. The town remained significantly impoverished in the absence of a permanent political settlement between the two sides in the past two decades.

The city contains several monuments of medieval Georgian architecture, with the Kavti Church of St. George being the oldest one dating back to the 8th-10th centuries.

On August 21, 2008, a world-known[38] Russian conductor and director of the Mariinsky Theatre, of Ossetian origin, Valery Gergiev conducted a concert near the ruined building of South Ossetian parliament in memory of the victims of the war in South Ossetia.[39]

Transport

There was a railway service before 1991 at the Tskhinvali Railway station connecting the city with Gori.

International relations

See also

Notes

- South Ossetia's status is disputed. It considers itself to be an independent state, but this is recognised by only a few other countries. The Georgian government and most of the world's other states consider South Ossetia de jure a part of Georgia's territory.

- http://ugosstat.ru/statisticheskij-sbornik-za-i-kvartal-2019-g/

- (in Russian)Словарь географических названий

- Bedoshvili, Guram (2002). Etymological-Explanatory Dictionary of Georgian Toponyms. Tbilisi: Bakur Sulakauri Publishing. p. 479.

- (in Russian)ИСТОРИЯ ЦАРСТВА ГРУЗИНСКОГО ("History of the Georgian Kingdom"), Вахушти Багратиони. Retrieved from vostlit.info on 24.08.2008

- The Permanent Committee on Geographical Names (UK) (2007) "Georgia: a toponymic note concerning South Ossetia"

- "Цхинвали. Электронная еврейская энциклопедия". 2006-07-04. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- "Attacks damaged or destroyed 70% of buildings — Tskhinvali mayor". RIA Novosti. 12 August 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-12.

- "Targeting civilians' homes". Russia Today. 12 August 2008. Archived from the original on 5 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-04.

- "Грузины снимали свои преступления на видео". Vesti.Ru. 3 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-03.

- Svante E. Cornell; Johanna Popjanevski; Niklas Nilsson (August 2008). "Russia's War in Georgia: Causes and Implications for Georgia and the World" (PDF). Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program Policy papers. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 May 2013.

- Россия начнет войну против Грузии предположительно в августе - П. Фельгенгауер (in Russian). Gruziya Online. 20 June 2008.

- Чеченцы расписали сценарий войны России против Грузии (in Russian). MIGnews. 5 July 2008.

- Tanks 2010, p. 44.

- Brian Whitmore (12 September 2008). "Is The Clock Ticking For Saakashvili?'". Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty.

- Marc Champion; Andrew Osborn (16 August 2008). "Smoldering Feud, Then War". The Wall Street Journal.

- Luke Harding (19 November 2008). "Georgia calls on EU for independent inquiry into war". The Guardian.

- Jean-Rodrigue Paré (13 February 2009). "The Conflict Between Russia and Georgia". Parliament of Canada.

- Van Herpen 2014, p. 214.

- Dunlop 2012, p. 93.

- В Цхинвали прибыли 300 добровольцев из Северной Осетии (in Russian). Lenta.ru. 4 August 2008.

- "Russia vows to defend S Ossetia". BBC News. 5 August 2008.

- Dunlop 2012, p. 95.

- Martin Malek (March 2009). "Georgia & Russia: The 'Unknown' Prelude to the 'Five Day War'". Caucasian Review of International Affairs. 3 (2): 227–232.

- Maria Bogdarenko (6 August 2008). Шашки наголо (in Russian). Nezavisimaya Gazeta. Archived from the original on 30 May 2009.

- Volume II 2009, p. 208.

- Peter Finn (17 August 2008). "A Two-Sided Descent into Full-Scale War". The Washington Post.

- Tanks 2010, p. 46.

- "On the eve of war: The Sequence of events on august 7, 2008" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011.

- "Spot Report: Update on the situation in the zone of the Georgian-Ossetian conflict" (PDF). OSCE. 7 August 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2009.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "UNHCR - UNHCR secures safe passage for Georgians fearing further fighting". UNHCR. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- "Список погибших жителей Южной Осетии". Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- "Jewish Quarter targeted in Georgian offensive". Russia Today. August 21, 2008. Archived from the original on August 21, 2008.

- Илларионов Андрей. "Эхо Москвы :: Разворот Ситуация в Южной Осетии и Грузии: Андрей Илларионов". Эхо Москвы. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- "How To Screw Up A War Story: The New York Times At Work - By Mark Ames - The eXiled". Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- "Climate: Tskhinval". Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- "Life and tempo of a maestro". The Sydney Morning Herald. 28 September 2006.

- "Blitzed Ossetian city hosts classical concert". Russia Today. August 21, 2008. Archived from the original on August 26, 2008.

External links

| Look up ცხინვალი in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tskhinvali. |

Sites

- Site of Tskhinvali: information, news, video, photos, etc. — www.chinval.ru

Pictures

References

- Tsotniahsvili, MM. (1986). History of Tskhinvali (in Georgian). Tskhinvali.