Smelt-whiting fishing

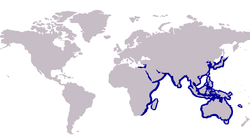

Smelt-whiting is the common name for various species of the family Sillaginidae. The Sillaginidae are distributed throughout the Indo-Pacific region, ranging from the west coast of Africa to Japan and Taiwan in the east, as well occupying as a number of small islands including New Caledonia in the Pacific Ocean.[1] Well known members of this family include King George whiting, Japanese whiting, northern whiting, sand whiting and school whiting.

Characteristics

Smelt-whitings are primarily inshore marine fishes inhabiting stretches of coastal waters, although a few species move offshore in their adult stages to deep sand banks or reefs to a maximum known depth of 180 m.[2] All species primarily occupy sandy, silty or muddy substrates, often using seagrass or reef as cover. They commonly inhabit tidal flats, beach zones, broken bottoms and large areas of uniform substrate. Although the family is marine, many species inhabit estuarine environments, with some such as Sillaginopsis panijus also found in the upper reaches of the estuary.[3] Each species often occupies a specific niche to avoid competition with co-occurring sillaginids, often inhabiting a specific substrate type, depth, or making use of surf zones and estuaries.[4] No members of the family are known to undergo migratory movements, and have been shown to be relatively weak swimmers, relying on currents to disperse juveniles.

The smelt-whitings are benthic carnivores, with all of the species whose diets have been studied showing similar prey preferences. Studies from the waters of Thailand, Philippines and Australia have shown that polychaetes, a variety of crustaceans, molluscs and to a lesser extent echinoderms and fish are the predominant prey items of the family.[5][6][7] Commonly taken crustaceans include decapods, copepods and isopods, while the predominant molluscs taken are various species of bivalves, especially the unprotected siphon filters that protrude from the shells. All larger whiting feed by using their protrusile jaws and tube-like mouths to suck up various types of prey from in, on or above the ocean substrate,[4] as well as using their nose as a 'plough' to dig through the substrate.[8] There is a large body of evidence that shows whiting do not rely on visual cues when feeding, instead using a system based on the vibrations emitted by their prey.[9]

In Australia and Japan, members of the family are highly sought after by anglers for their sporting and eating qualities, with anglers often taking more than commercial fishermen in some areas.[10] The fishing techniques for all sillaginids are quite similar, with the shallow habitats often requiring light line and quiet movements. Whiting are also popular in part due to their accessibility, with tidal flats around beaches, estuaries and jetties common habitats from where many whiting species are caught without need for a boat.[11] Tidal movements also affect catches, as do lunar phases, causing whiting to 'bite' when the tide is changing. Tackle used is kept light to avoid spooking the fish, and often requires only a simple setup, with a hook and light sinker tied directly to the mainline usually effective. In deeper water fished from boats or where currents are strong, more complex rigs are used, often with hooks tied to dropper loops on the trace.[11] in Australia, some specialist whiting fishermen who target the fish in the surf or on shallow banks use red beads or tubing to attract the fish, claiming the method produces more fish.[12] The bait used is normally anything from the surrounding environment which the whiting naturally prey on, with polychaetes, bivalves, crustaceans such as prawns and crabs, cephalopods and small fish effective for most species. As with most species, live bait is known to produce better catches. Lure fishing for whiting is not normally practiced, but saltwater flies have been used to good effect, as have small soft plastic lures.[13] In some areas, restrictions to the amount and size of fish are in place and enforced by fishery authorities.[14]

Recreational fisheries

Sand whiting

Sand whiting are commonly sought after by anglers due to their reputation as a food fish, and due to their relative accessibility, with large catches possible from many shore-based locations. The catches of recreational fishermen may exceed the catches of professionals, with studies showing Queensland had over twice the amount of fish taken by anglers in 2000.[15]

The species is commonly caught throughout its habitat, with sand flats, tidal gutters in estuaries and surf beaches commonly having producing good catches. Excessively shallow water, especially in proximity to Zostera beds may produce numerous undersized fish, and may be avoided if the young fish are too prevalent. Due to their preferred habitat, light lines with minimal weight added are employed to avoid spooking the fish, with a small running bean or ball sinker commonly rigged above a size 4 or 6 hook.[11] Specialist whiting fishermen often use a red piece of tubing or beads to attract the whiting; whether this works has yet to be proved, but anecdotal evidence shows the fishermen's catches don't suffer. Baits used resemble the species natural prey, with prawns, nippers, a variety of bivalves and beach worms most often used, with more successful catches obtained using live bait.[13]

In New South Wales, sand whiting have a minimum legal length of 27 cm to be taken and a daily personal bag limit of 20 applies,[16] while in Queensland there is a minimum size of 23 cm and no bag limit.[17]

Sand whiting are used themselves as live bait for larger species such as mulloway, mangrove jack and large flathead, although anglers must still adhere to the minimum size limit.[18]

Yellowfin whiting

Yellowfin whiting have become a major target for anglers in both South and Western Australia for a number of reasons: they are very good table fish, they provide good sport on light line, and are easily accessible from beaches and jetties, with a boat not necessary for their capture. Yellowfin whiting are actually most commonly targeted from beaches, estuaries and jetties constructed over shallow waters, with good catches often made on the ingoing and outgoing period of the tide. Due to their easily spooked nature, tackle used to capture the fish is usually very light, with lines kept below 6 kg, hooks below size 4, and sinkers to an absolute minimum as heavy lines and sinkers often scare away the fish.[13] Specialist whiting fishermen often attach a red bead or piece of tubing directly above the hook to attract the fish, although the usefulness of this is debated. The most common bait used is 'beach worms', which may be from a variety of families, with prawns, cockles and squid occasionally taking good catches also. Lure and fly fishing for the species is poorly developed, with their shy nature preventing these methods from being effectively used.[13]

The recreational catch often is greater than the commercial catch in some areas, with a survey carried out in Blackwood River indicating 120 700 fish were taken in a year by anglers.[19] A similar survey conducted in the South Australian Gulfs found recreational fishermen accounted for 28% of the entire yellowfin whiting taken during the 2000/2001 period, representing over 50 tonnes of fish.[20] Recreational bag limits have been put in place to prevent over-exploitation by anglers in both states, with South Australia imposing a minimum size limit of 24 cm and a bag limit of 20 fish on anglers.[21] In Western Australia, there is no minimum size limit, but a bag limit of 40 fish in combination with school whitings (Sillago bassensis and Sillago vittata).[22]

King George whiting

The King George whiting is endemic to Australia, inhabiting the south coast of the country from Jurien Bay, Western Australia to Botany Bay, New South Wales in the east. The King George whiting is the only member of the genus Sillaginodes and the largest member of the smelt-whiting family Sillaginidae, growing to a length of 72 cm and 4.8 kg in weight. The species is readily distinguishable from other Australian whitings by its unique pattern of spots, as well as its highly elongate shape.

In Southern Australia, the King George whiting is often the sole target for fishermen who seek it for its high quality eating. A number of coastal towns rely heavily on the species as a tourism drawcard for anglers seeking a range of fish and crustacean species, but King George whiting is often the most desired catch.[13] They are a relatively easy species to catch, with no special baits, rigs or techniques required and are often caught from jetties, beaches and rocks; meaning a boat is not necessary. Simple rigs such varieties of running ball sinker or paternoster rigs are commonly used, with a fixed sinker employed in area of high tidal movement.[11] As mentioned previously, molluscs, particularly the Goolwa cockle are common bait, with varieties of worms, gents, squid, cuttlefish, fish pieces and other shellfish also commonly successful. The larger fish inhabiting deep reefs are often caught on whole pilchards while fishing for snapper and morwong.[11]

The King George whiting has differing size and bag limits for anglers in different states. In Victoria, there is a minimum size limit of 27 cm and a bag limit of 20 per person.[23] South Australia is divided into two zones concerning the taking of this species, with fish caught east of longitude 136° restricted to a minimum length of 31 cm and fish caught to the west of longitude 136° having a minimum length of 30 cm. In both divisions, the bag limit is 12 fish per person.[24] Western Australia has set a minimum legal limit of 28 cm and a bag limit of 8 per person.[25]

School whiting

There are three species of three 'school whiting' that inhabit southern Australia and have a very similar appearance.

- The southern school whiting (also known as the silver whiting or trawl whiting) is a common smelt whiting that inhabits the south and south-west coasts of Australia, and is closely related to the eastern school whiting. It is commonly caught by recreational fishermen, often while fishing for related species, especially the sought after King George whiting. Southern school whiting are taken on a variety of baits, with their natural prey such as marine worms, molluscs, prawns and sardines often used.[13] Due to their schooling nature, many fish can be caught in a single fishing period, although most authorities ask for excess fish to be returned to the water alive.[26] In Western Australia, southern school whiting and yellowfin whiting have a combined bag limit of 40 per person with no size restrictions, with no regulations applying elsewhere.[22]

- The eastern school whiting (also known as the redspot whiting and the Bass Strait whiting) is endemic to Australia, distributed along the east coast from southern Queensland down to Tasmania and South Australia. It is primarily a target of commercial fishermen operating offshore seines and trawls, with recreational catches generally rare. The exception occurs when large amounts of the species have been taken by anglers as large schools pass through shallow waters along the coast.[27]

- The western school whiting (also known as the banded whiting, golden whiting and bastard whiting), is distributed along the Western Australian coast from Maud Landing in the north to Rottnest Island in the south. They are grow to 30 cm in length and 275 g in weight, and are considered to have good to excellent flesh for eating.[28] Due to their offshore nature in the south of Western Australia, they are rarely taken by recreational fishermen, while in the northern part of their range where they inhabit shallower waters, they are often overlooked for larger tropical species by anglers. Thus they are not a major recreational fishery. They respond to the same fishing styles as other whitings, generally using light lines and sinkers with worm or mollusc baits. They are caught off beaches, jetties and from boats.[12] There is no size restriction on the species, but a daily bag limit of 40 per person applies.[29]

Asian whiting

The Asian whiting are another smelt whiting, distributed along the Asian coastline from the Gulf of Thailand to Taiwan. A number of smelt-whiting species are present throughout the range of the Asian whiting and are taken as food for local consumption. There is often no distinction between species and the total catch of the species is unknown, but it certainly makes up a proportion of the whiting taken.[30] The most important fishery where the species is involved is in Taiwan.[8]

Japanese whiting

Japanese whiting were first recorded from Japan in 1843, but have subsequently been found to extend to Korea, China and Taiwan. It is one of the most common inshore species in Japan, greatly esteemed for its delicate flavour.[8] Recreational fishermen in Japan also take the species often, especially in summer, with the species relatively easy to access from land based fishing areas.[31]

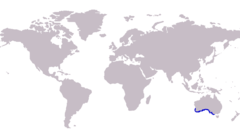

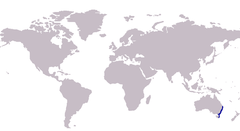

Range maps

Sand whiting

Sand whiting Yellowfin whiting

Yellowfin whiting King George whiting

King George whiting Southern school whiting

Southern school whiting Eastern school whiting

Eastern school whiting- Western school whiting

Asian whiting

Asian whiting- Japanese whiting

References

- Nelson, Joseph S. (2006). Fishes of the World. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 278–280. ISBN 0-471-25031-7.

- Hyndes, G.A.; I. C. Potter; S. A. Hesp (September 1996). "Relationships between the movements, growth, age structures, and reproductive biology of the teleosts Sillago burrus and S. vittata in temperate marine waters". Marine Biology. 126 (3): 549–558. doi:10.1007/BF00354637.

- Krishnayya, C.G. (1963). "On the use of otoliths in the determination of age and growth of the Gangetic whiting, Sillago panijus (Ham.Buch.), with notes on its fishery in Hooghly estuary". Indian Journal of Fisheries. 10: 391–412.

- Hyndes, G.A.; M. E. Platell; I. C. Potter (1997). "Relationships between diet and body size, mouth morphology, habitat and movements of six sillaginid species in coastal waters: implications for resource partitioning". Marine Biology. 128 (4): 585–598. doi:10.1007/s002270050125.

- Tongnunui, P.; Sano, M.; Kurokura, H. (2005). "Feeding habits of two sillaginid fishes, Sillago sihama and S-aeolus, at Sikao Bay, Trang Province, Thailand". Mer (Tokyo). 43 (1/2): 9–17. ISSN 0503-1540. Archived from the original on 2008-04-30. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- Mitsuhiro, Kato; Hiroshi Kohno; Yasuhiko Taki (November 1996). "Juveniles of two sillaginids,Sillago aeolus andS. sihama, occurring in a surf zone in the Philippines". Ichthyological Research. Springer Japan. 43 (4): 1341–8998. doi:10.1007/BF02347640.

- Hyndes, G.A.; M. E. Platell; I. C. Potter (June 1997). "Relationships between diet and body size, mouth morphology, habitat and movements of six sillaginid species in coastal waters: implications for resource partitioning". Marine Biology. Springer Berlin / Heidelberg. 128 (4): 585–598. doi:10.1007/s002270050125.

- McKay, R.J. (1992). FAO Species Catalogue: Vol. 14. Sillaginid Fishes Of The World (PDF). Rome: Food and Agricultural Organisation. pp. 19–20. ISBN 92-5-103123-1.

- Hadwen, W.L.; Russell, G.L.; Arthington, A.H. (1985). "The food, feeding habits and feeding structures of the whiting species Sillago sihama (ForsskaÊ l) and Sillago analis Whitley from Townsville, North Queensland, Australia". Journal of Fish Biology. 26: 411–427. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1985.tb04281.x.

- Wilkinson, J. (2004). NSW Fishing Industry: Changes and Challenges in the Twenty-First Century. Sydney: NSW Parliamentary Library Research Service. pp. 174–178. ISBN 0-7313-1768-8.

- Starling, S. (1988). The Australian Fishing Book. Hong Kong: Bacragas Pty. Ltd. p. 490. ISBN 0-7301-0141-X.

- Horrobin, P. (1997). Guide to Favourite Australian Fish. Singapore: Universal Magazines. pp. 102–103. ISSN 1037-2059.

- Horrobin, P. (1997). Guide to Favourite Australian Fish. Singapore: Universal Magazines. pp. 104–105.

- Department of Primary Industries (2007). "Recreational Fishing Guide". Limits and Closed Seasons. Government of Victoria. Archived from the original (pdf) on 2007-08-29. Retrieved 2007-10-10.

- Williams, L.E. (2002). Queensland's Fisheries Resources: Current conditions and recent trends 1988-2000. Brisbane: Department of Primary Industries Queensland. pp. 174–178. Archived from the original on 2007-08-29.

- New South Wales Department of Primary Industries. "Bag and Size Limits - Saltwater" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-08-17.

- Queensland Government Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries. "The Queensland East Coast Inshore Fin Fish Fishery Background paper: Size and bag limits" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-08-17.

- Downie, David. "Live-baiting Brisbane Estuaries". Retrieved 2007-08-17.

- Kailola, P.J.; Williams, M.J.; Stewart, R.E.; et al. (1993). "Australian fisheries resources". Bureau of Resource Sciences.

- Marine Scalefish Fishery Management Committee (2004–2005). "The Marine Scalefish Fishery" (PDF). Annual Report 2004-2005. PIRSA: 5–13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-15. Retrieved 2008-09-13.

- Primary Industries & Resources SA (December 2007). "South Australian Size, Bag and Boat Limits" (PDF). Pamphlet. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-08-03. Retrieved 2008-09-13.

- Western angler. "Whiting (Southern School & Yellowfin)". Archived from the original on 2007-09-09. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

- FishVictoria. "Whiting, King George". Archived from the original on 2007-08-21. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

- Primary Industries SA. "King George whiting". Retrieved 2007-07-21.

- Western angler. "King George whiting". Archived from the original on 2007-09-09. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

- Primary Industries SA. "Legal Limits". Retrieved 2007-07-21.

- McKay, R.J. (1985). "A Revision of the Fishes of the Family Silaginidae". Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. 22 (1): 1–73.

- Hutchins, B.; Swainston, R. (1986). Sea Fishes of Southern Australia: Complete Field Guide for Anglers and Divers. Melbourne: Swainston Publishing. p. 187. ISBN 1-86252-661-3.

- Department of Fisheries (January 2008). Recreational Fishing Guide: Gascoyne Region. The Government of Western Australia.

- McKay, R.J. (1999). Carpenter, K.E.; Niem, V.H. (eds.). FAO species identification guide for fishery purposes: The Living Marine Resources Of The Western Central Pacific: Volume 4 Bony fishes, part 2 (Mugilidae to Carangidae). Rome: Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations. pp. 2069–2790. ISBN 92-5-104301-9.

- Kanoyama Japanese Restaurant. "Fish Facts". Archived from the original on 2007-09-20. Retrieved 2007-09-07.