Slavomolisano dialect

Slavomolisano, also known as Molise Slavic or Molise Croatian, is a variety of Shtokavian Serbo-Croatian spoken by Italian Croats in the province of Campobasso, in the Molise Region of southern Italy, in the villages of Montemitro (Mundimitar), Acquaviva Collecroce (Živavoda Kruč) and San Felice del Molise (Štifilić). There are fewer than 1,000 active speakers, and fewer than 2,000 passive speakers.[1]

| Molise Slavic | |

|---|---|

| Molise Croatian, Slavomolisano | |

| na-našu, na-našo | |

| Native to | Italy |

| Region | Molise |

| Ethnicity | Molise Croats |

Native speakers | < 1,000 (2012)[1] |

Indo-European

| |

| Latin script[2] | |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | svm |

| Glottolog | slav1254[3] |

| South Slavic languages and dialects | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Western South Slavic

|

||||||

|

Eastern South Slavic

|

||||||

|

Transitional dialects

|

||||||

|

Alphabets

|

||||||

It has been preserved since a group of Croats emigrated from Dalmatia due to the advancing Ottoman Turks. The residents of these villages speak a Shtokavian dialect with an Ikavian accent, and a strong Southern Chakavian adstratum. The Molise Croats consider themselves to be Slavic Italians, with South Slavic heritage and who speak a Slavic language, rather than simply ethnic Slavs or Croats.[1] Some speakers call themselves Zlavi or Harvati and call their language simply na našo ("our language").

History

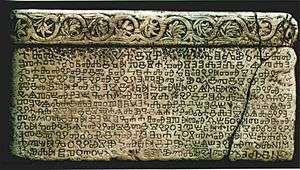

According to evidence Molise Croats arrived in the early 16th century.[4] The documents from the episcopal archive of Termoli indicate that Molise Croats arrived 1518 in Stifilić (San Felice).[5] A stone inscription on the church in Palata, destroyed in 1930s, read Hoc Primum Dalmatiae Gentis Incoluere Castrum Ac Fundamentis Erexere Templum Anno 1531 (Residents of Dalmatia first settled the town and founded the church in 1531).[4] The absence of any Turkish word additionally proves this dating.[4][6]

The language of Molise Croats is considered to be important because of its archaism, preserved old folk songs and tradition.[7][8] The basic vocabulary was done by Milan Rešetar (in monography), Agostina Piccoli (along Antonio Sammartino, Snježana Marčec and Mira Menac-Mihalić) in Rječnik moliškohrvatskoga govora Mundimitra (Dizionario dell' idioma croato-molisano di Montemitro), and Dizionario croato molisano di Acquaviva Collecroce, the grammar Gramatika moliškohrvatskoga jezika (Grammatica della lingua croato-molisana), as well work Jezik i porijeklo stanovnika slavenskih naseobina u pokrajini Molise by Anita Sujoldžić, Božidar Finka, Petar Šimunović and Pavao Rudan.[9][10]

The language of Molise Croats belongs to Western Shtokavian dialect of Ikavian accent,[11] with many features and lexemes of Chakavian dialect.[11][12] The lexicon comparison points to the similarity with language of Sumartin on Brač, Sućuraj on Hvar, and Račišće on Korčula,[9][12] settlements founded almost in the same time as those in Molise,[9] and together point to the similarity of several settlements in South-Western and Western Istria (see Southwestern Istrian dialect), formed by the population of Makarska hinterland and Western Herzegovina.[9][10]

Giacomo Scotti noted that the ethnic identity and language was only preserved in San Felice, Montemitro and Acquaviva Collecroce thanks to the geographical and transport distance of the villages from the sea.[13] Josip Smodlaka noted that during his visit in the early 1900s the residents of Palata still knew to speak in Croatian language about basic terms like home and field works, but if the conversation touched more complex concepts they had to use the Italian language.[14]

The language is taught in primary schools and the signs in villages are bilingual. However, the sociolinguistic status of the language differs among the three villages where it is spoken: in San Felice del Molise, it is spoken only by old people, whereas in Acquaviva Collecroce it is also spoken by young adults and adolescents, and in Montemitro it is even spoken by children, generally alongside Italian.[15]

Features

- The analytic do + genitive replaces the synthetic independent genitive. In Italian it is del- + noun, since Italian has lost all its cases.

- do replaced by od.

- Disappearance of the neuter gender for nouns. Most neuter nouns have become masculine instead under the influence of Italian, and their unstressed final vowels have almost universally lowered to /a/.[15] In the Montemitro dialect, however, all neuter nouns have become masculine, and vowel lowering has not occurred.[15]

- Some feminine -i- stem nouns have become masculine. Those that have not have instead gained a final -a and joined the -a- stem inflectional paradigm. Thus feminine kost, "bone", has become masculine but retained its form, while feminine stvar, "thing", has become stvarḁ but retained its gender.[15]

- Simplification of declension classes. All feminine nouns have the same case inflection paradigm, and all masculine nouns have one of two case inflection paradigms (animate or inanimate).[15]

- Only the nominative, dative, and accusative cases can be used in their bare forms (without prepositions), and even then only when expressing the syntactic roles of subject, direct object, or recipient.[15]

- Loss of the locative case.[15]

- Slavic verb aspect is preserved, except in the past tense imperfective verbs are attested only in the Slavic imperfect (bihu, they were), and perfective verbs only in the perfect (je izaša, he has come out). There is no colloquial imperfect in the modern West South Slavic languages. Italian has aspect in the past tense that works in a similar fashion (impf. portava, "he was carrying", versus perf. ha portato, "he has carried").

- Slavic conjunctions replaced by Italian or local ones: ke, "what" (Cr. što, also ke - Cr. da, "that", It. che); e, oš, "and" (Cr i, It. e); ma, "but" (Cr. ali, no, It. ma); se, "if" (Cr. ako, It. se).

- An indefinite article is in regular use: na, often written 'na, possibly derived from earlier jedna, "one", via Italian una.

- Structural changes in genders. Notably, njevog does not agree with the possessor's gender (Cr. njegov or njezin, his or her). Italian suo and its forms likewise does not, but with the object's gender instead.

- As in Italian, the perfective enclitic is tightly bound to the verb and always stands before it: je izaša, "is let loose" (Cr. facul. je izašao or izašao je), Italian è rilasciato.

- Devoicing or loss of final short vowels, thus e.g. mlěko > mblikḁ, "milk", more > mor, "sea", nebo > nebḁ, "sky".[15]

Phonology

Consonants

The consonant system of Molise Slavic is as follows, with parenthesized consonants indicating sounds that appear only as allophones:[16]

| Labial | Dental | Palato- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | p b | t d | c ɟ | k g | |

| Affricate | t͡s d͡z | t͡ʃ d͡ʒ | |||

| Fricative | f v | s z | ʃ ʒ | ç ʝ | x (ɣ) |

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | (ŋ) | |

| Lateral | l | ʎ | |||

| Trill | r | ||||

| Approximant | (w) | (j) |

- Unlike the standard Serbo-Croatian lects, there are no alveolo-palatal phonemes /t͡ɕ/ and /d͡ʑ/ (ć and đ), as they have largely merged with the palato-alveolar /t͡ʃ/ and /d͡ʒ/ (č and dž).[16] However, in cases where standard Serbo-Croatian /t͡ɕ/ reflects Proto-Slavic *jt, the corresponding phoneme in Molise Slavic is instead /c/.[16] In some cases standard /d͡ʑ/ corresponds to Molise /ʝ/, as in Chakavian.[16]

- /f/, /d͡z/, /d͡ʒ/, /c/, /ɟ/, and /ç/ appear mostly in loanwords.[16]

- The velar fricative [ɣ] is inserted by some speakers between vowels to eliminate hiatus; some speakers use [v] in this role instead.[16] Rarely, [ɣ] can appear as an intervocalic allophone of /x/.[16]

- /n/ is realized as [ŋ] before velar plosives.[16]

- A prothetic [j] is regularly inserted before initial /i/.[16]

- A /u̥/ adjacent to a vowel is realized as a [w].[16] Etymologically, it derives from a /v/ next to an unvoiced plosive; thus standard Serbo-Croatian [stvâːr] (‘thing’) corresponds to Molise Slavic [ˈstwaːrḁ].[16]

- Some speakers realize /ʎ/ as [j], /gʎ/ as [ɟ], and /kʎ/ as [c].[16]

- After a short vowel, the following consonant may optionally be geminated.[16]

Vowels

The vocalic system of Molise Slavic has seven distinct vowel qualities, as follows:[16]

| Front | Central | Back |

|---|---|---|

| i | u | |

| e | o | |

| ɛ | ɔ | |

| a |

- Besides these vowels, there is also a syllabic /r̩/ that functions as a vowel.[16] Some speakers insert an epenthetic [ɛ] before the /r/ instead of pronouncing the /r/ as syllabic.[16]

- There are two tones, rising and falling. A falling tone can be found only on single stressed initial syllables. A rising tone spreads over two equally-stressed syllables (or one stressed followed by one more stressed), except in cases where the second syllable has been lost. If the second syllable is long, some speakers only stress the second syllable.[16]

- An opposition exists between long and short vowels, but only in stressed position. Vowels with a falling tone are sometimes long, and the second vowel with a rising tone is always long unless it is word-final, in which case the first vowel with a rising tone is long instead if the second vowel is voiceless or lost. Vowel length is only distinctive with falling tone; with rising tone, it is entirely predictable.[16]

- /ɛ/ and /ɔ/ are found almost exclusively in loanwords.[16]

- [ɪ] appears as an allophone of unstressed /i/, especially next to nasal consonants.[16]

- In posttonic position, there is a tendency to lower vowels, so that both /o/ and /e/ merge with /a/ (though some conservative speakers do not have this merger). /i/ and /u/ are also often lowered to [ɪ] and [ʊ], but remain distinct.[16]

- Etymologically short vowels become voiceless in final position. Among younger speakers they are often dropped altogether. /i̥/ is almost universally dropped, /ḁ/ (and /e̥/ and /o̥/, which have largely merged with /ḁ/) less commonly, and /u̥/ is retained by almost everyone in all positions.[16]

Samples

A text collected by Milan Rešetar in 1911 (here superscripts indicate voiceless vowels):[17]

| Slavomolisano | Standard Serbo-Croatian | English translation |

|---|---|---|

| Nu votu biš na-lisic oš na-kalandrel; su vrl grańe na-po. Lisic je rekla kalandrel: "Sad’ ti grańe, ka ja-ću-ga plivit." Sa je-rivala ka’ sa-plivaš; je rekla lisic: "Pliv’ ti sa’, ke ja-ću-ga poranat." Kalandral je-plivila grańe. Kada sa ranaše, je rekla lisic: "Sa’ ranaj ti, ke ja-ću-ga štoknit." Je-rivala za-ga-štoknit; je rekla lisic: "Sa’ štokni ga-ti, ke ja-ću-ga zabrat." Je rivala za zabrat; je rekla lisic: "Zabri-ga ti, ke ja-ću-ga razdilit." Je pola kalandrela za-ga-razdilit; lisic je-vrla kučak zdola meste. Sa je rekla lisic kalandrel: "Vam’ meste!"; kaladrela je-vazela meste, je jizaša kučak, je kumenca lajat, — kalandrela je ušl e lisic je-rekla: "Grańe men — slamu teb!" | Jedanput bješe jedna lisica i jedna ševa; metnule su kukuruz napola. Lisica je rekla ševi: "Sadi ti kukuruz, jer ja ću ga plijeviti." Sad je došlo (vrijeme), kada se plijevljaše; rekla je lisica: "Plijevi ti sad, jer ja ću ga opkopati." Ševa je plijevila kukuruz. Kada se opkapaše, rekla je lisica: "Sada opkapaj ti, jer ja ću rezati." Došlo je (vrijeme) da se reže; rekla je lisica: "Sad ga reži ti, jer ja ću ga probrati." Došlo je (vrijeme) da se probere; rekla je lisica: "Proberi ga ti, jer ja ću ga razdijeliti." Pošla je ševa da ga dijeli; lisica je metnula kučka pod vagan. Sad je rekla lisica ševi: "Uzmi vagan!"; ševa je uzela vagan, izašao je kučak, počeo je lajati, — ševa je pobjegla, a lisica je rekla: "Kukuruz meni — slamu tebi!" | Once there was a fox and a lark; they divided corn in halves. The fox said to the lark: "You plant the corn, for I’ll weed out the chaff." The time came to weed out the chaff; the fox said: "You weed now, for I’ll dig around it." The lark weeded out the chaff from the corn. When it came time to dig, the fox said: "Now you dig, for I’ll reap it." The time came to reap it; the fox said: "Now you reap it, for I will gather it." The time came to gather; the fox said: "You gather it, for I’ll divide it up." The lark went to divide it up; the fox placed a dog under the weighing pan. Now the fox said to the lark: "Take the weighing pan!"; the lark took the pan, the dog came out, he began to bark, — the lark fled, but the fox said: "The corn for me — the straw for you!" |

An anonymous poem (reprinted in Hrvatske Novine: Tajednik Gradišćanskih Hrvatov, winner of a competition in Molise):

- SIN MOJ

Mo prosič solite saki dan

ma što činiš, ne govoreš maj

je funia dan, je počela noča,

maneštra se mrzli za te čeka.

Letu vlase e tvoja mat

gleda vane za te vit.

Boli život za sta zgoro,

ma samo mat te hoče dobro.

Sin moj!

Nimam već suze za još plaka

nimam već riče za govorat.

Srce se guli za te misli

što ti prodava, oni ke sve te išće!

Palako govoru, čelkadi saki dan,

ke je dola droga na vi grad.

Sin moj!

Tvoje oč, bihu toko lipe,

sada jesu mrtve,

Boga ja molim, da ti živiš

droga ja hočem da ti zabiš,

doma te čekam, ke se vrniš,

Solite ke mi prosiš,

kupiš paradis, ma smrtu platiš.

A section of The Little Prince, as translated into Molise Slavic by Walter Breu and Nicola Gliosca:

| Slavomolisano | Standard Serbo-Croatian | English translation |

|---|---|---|

| A! Mali kraljič, ja sa razumija, na mala na votu, naka, tvoj mali život malingonik. Ti s'bi jima sa čuda vrima kana dištracijunu sama ono slako do sutanji. Ja sa znaja ovu malu aš novu stvaru, dòp četar dana jistru, kada ti s'mi reka: Su mi čuda drage sutanja. | Ah! Mali prinče, tako sam, malo po malo, shvatio tvoj mali, tužni život. Tebi je dugo vremena jedina razonoda bila samo ljepota sunčevih zalazaka! Tu sam novu pojedinost saznao četvrtog dana ujutro kad si mi rekao: Jako volim zalaske sunca. | Oh, little prince! Bit by bit I came to understand the secrets of your sad little life. For a long time you had found your only entertainment in the quiet pleasure of looking at the sunset. I learned that new detail on the morning of the fourth day, when you said to me: I am very fond of sunsets. |

Dictionaries

- From: Josip Lisac: Dva moliškohrvatska rječnika, Mogućnosti 10/12, 2000.

- Walter Breu-Giovanni Piccoli (con aiuto di Snježana Marčec), Dizionario croatomolisano di Acquaviva-Collecroce, 2000, Campobasso 2000

- Ag. Piccoli-Antonio Samartino, Dizionario dell' idioma croato-molisano di Montemitro/Rječnik moliškohrvatskih govora Mundimitra, Matica Hrvatska Mundimitar - Zagreb, 2000.

- Giovanni Piccoli: Lessico del dialetto di Acquaviva-Collecroce, Rome, 1967

- Božidar Vidov: Rječnik ikavsko-štokavskih govora molizanskih Hrvata u srednjoj Italiji, Mundimitar, Štifilić, Kruč, Toronto, 1972.

- Tatjana Crisman: Dall' altra parte del mare. Le colonie croate del Molise, Rome, 1980

- Angelo Genova: Ko jesmo bolje: Ko bihmo, Vasto, 1990.

References

- Breu, Walter (2012-03-06). "Request for New Language Code Element in ISO 639-3" (PDF). ISO 639-3 Registration Authority. Retrieved 2013-06-30.

- Slavomolisano at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Slavomolisano". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Telišman 1987, p. 187.

- Telišman 1987, p. 188.

- Perinić 2006, p. 94.

- Šimunović 2012, p. 197–198, 202–203.

- Perinić 2006, p. 99–100.

- Šimunović 2012, p. 194.

- Perinić 2006, p. 97.

- Šimunović 2012, p. 193.

- Perinić 2006, p. 96.

- Telišman 1987, p. 189.

- Telišman 1987, p. 190.

- Marra, Antonietta. Contact Phenomena in the Slavic of Molise: some remarks about nouns and prepositional phrases in Morphologies in Contact (2012), p.265 et seq.

- Walter Breu and Giovanni Piccoli (2000), Dizionario croato molisano di Acquaviva Collecroce: Dizionario plurilingue della lingua slava della minoranza di provenienza dalmata di Acquaviva Collecroce in Provincia di Campobasso (Parte grammaticale).

- Milan Rešetar (1911), Die Serbokroatischen Kolonien Süditaliens.

- Telišman, Tihomir (1987). "Neke odrednice etničkog identiteta Moliških Hrvata u južnoj Italiji" [Some determinants of ethnic identity of Molise Croats in Southern Italy]. Migration and Ethnic Themes (in Croatian). Institute for Migration and Ethnic Studies. 3 (2).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Piccoli, Agostina (1994). "20 000 Molisini di origine Slava (Prilog boljem poznavanju moliških Hrvata)" [20,000 Molise residents of Slav origin (Appendix for better knowledge of the Molise Croats)]. Studia ethnologica Croatica (in Croatian). Department of Ethnology and Cultural Anthropology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb. 5 (1).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Perinić, Ana (2006). "Moliški Hrvati: Rekonstrukcija kreiranja ireprezentacijejednog etničkog identiteta" [Molise Croats: Reconstruction of creation and representation of an ethnic identity]. Etnološka tribina (in Croatian). Croatian Ethnological Society and Department of Ethnology and Cultural Anthropology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb. 36 (29).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Šimunović, Petar (May 2012). "Moliški Hrvati i njihova imena: Molize i druga naselja u južnoj Italiji u motrištu tamošnjih hrvatskih onomastičkih podataka" [Molise Croats and their names: Molise and other settlements in southern Italy in the standpoint of the local Croatian onomastic data]. Folia onomastica Croatica (in Croatian) (20): 189–205. Retrieved 24 July 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Bibliography

- Aranza, Josip (1892), Woher die südslavischen Colonien in Süditalien (Archiv für slavische Philologie, XIV, pp. 78–82, Berlin.

- Bada, Maria (2005), “Sociolinguistica interazionale nelle comunità croatofone del Molise e in contesto scolastico”, Itinerari, XLIV, 3: 73-90.

- Bada, Maria (2007a), “Istruzione bilingue e programmazione didattica per le minoranze alloglotte: l’area croato-molisana”, Itinerari, XLVI, 1: 81-103.

- Bada, Maria (2007b), “The Nā-naš Variety in Molise (Italy): Sociolinguistic Patterns and Bilingual Education”, Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Minority Languages (ICML 11), University of Pécs, Hungary, 5–6 July 2007.

- Bada, Maria (2007c), "Repertori allofoni e pratiche metacomunicative in classe: il caso del croato-molisano”. In: C. Consani e P. Desideri (a cura di), "Alloglossia e comunità alloglotte nell’Italia contemporanea. Teorie, applicazioni e descrizioni, prospettive". Atti del XLI Congresso Internazionale della Società Italiana di Linguistica (SLI), 27–29 settembre 2007, Bulzoni, Roma: 317-338.

- Bada, Maria (2008a), “Politica linguistica e istruzione bilingue nell’area croatofona del Molise”. In: G. Agresti e F. Rosati (a cura di), "Les droits linguistiques en Europe et ailleurs /Linguistic Rights: Europe and Beyond", Atti delle Prime Giornate dei Diritti Linguistici. Università di Teramo, 11-12 giugno 2007, Aracne, Roma: 101-128. abstract pdf

- Bada, Maria (2008b), “Acquisition Planning, autopercezione dei parlanti alloglotti e competenza metalinguistica”. In: G. Berruto, J. Brincat, S. Caruana e C. Andorno (a cura di), "Atti dell'8° Congresso dell'Associazione Italiana di Linguistica Applicata. Lingua, cultura e cittadinanza in contesti migratori. Europa e area mediterranea", Malta, 21-22 febbraio 2008, Guerra, Perugia: 191-210.

- Bada, Maria (2009a), "La minoranza croata del Molise: un'indagine sociolinguistica e glottodidattica". In: Rita Franceschini (a cura di) "Le facce del plurilinguismo: fra metodologia, applicazione e neurolinguistica", Franco Angeli, Milano: 100-169.

- Badurina, Teodoro (1950), Rotas Opera Tenet Arepo Sator Rome.

- Barone, Charles, La parlata croata di Acquaviva Collecroce. Studio fonetico e fonologico, Firenze, Leo S. Olschki Editor, MCMXCV, p. 206 (Accademia Toscana di Scienze e Lettere »La Colombaria«. »Studi CXLVI).

- Breu, W. (1990), Sprache und Sprachverhalten in den slavischen Dörfern des Molise (Süditalien). In: W. BREU (a cura di), Slavistische Linguistik 1989. Münich, 35 65.

- Breu, W. (1998), Romanisches Adstrat im Moliseslavischen. In: Die Welt der Slaven 43, 339-354.

- Breu, W. / Piccoli, G. con la collaborazione di Snježana Marčec (2000), Dizionario croato molisano di Acquaviva Collecroce. Dizionario plurilingue della lingua slava della minoranza di provenienza dalmata di Acquaviva Collecroce in Provincia di Campobasso. Dizionario, registri, grammatica, testi. Campobasso.

- Breu, W. (2003a), Bilingualism and linguistic interference in the Slavic-Romance contact area of Molise (Southern Italy). In: R. Eckhardt et al. (a cura di), Words in Time. Diachronic Semantics from Different Points of View. Berlin/New York, 351-373

- Breu, W. a cura di (2005), L'influsso dell'italiano sulla grammatica delle lingue minoritarie. Università della Calabria. In: W. Breu, Il sistema degli articoli nello slavo molisano: eccezione a un universale tipologico, 111-139; A. Marra, Mutamenti e persistenze nelle forme di futuro dello slavo molisano, 141-166; G. Piccoli, L'influsso dell'italiano nella sintassi del periodo del croato (slavo) molisano, 167-175.

- Gliosca, N. (2004). Poesie di un vecchio quaderno (a cura di G. Piscicelli). In: Komoštre/Kamastra. Rivista Bilingue di Cultura e Attualità delle Minoranze Linguistiche degli Arbëreshë e Croati del Molise 8/3, 8-9.

- Heršak, Emil (1982). Hrvati u talijanskoj pokrajini Molise", Teme o iseljeništvu. br. 11, Zagreb: Centar za Istraživanje Migracija, 1982, 49 str. lit 16.

- Hraste, Mate (1964). Govori jugozapadne Istre (Zagreb.

- Muljačić, Žarko (1996). Charles Barone, La parlata croata di Acquaviva Collecroce (189-190), »Čakavska rič« XXIV (1996) br. 1-2 Split Siječanj- Prosinac.

- Piccoli, A. and Sammartino, A. (2000). Dizionario croato-molisano di Montemitro, Fondazione "Agostina Piccoli", Montemitro – Matica Hrvatska, Zagreb.

- Reißmüller, Johann Georg. Slavenske riječi u Apeninima (Frankfurter Allgemeine, n. 212 del 13.11.1969.

- Rešetar, M. (1997), Le colonie serbocroate nell'Italia meridionale. A cura di W. Breu e M. Gardenghi (Italian translation from the original German Die Serbokroatischen Kolonien Süditaliens, Vienna 1911 with preface, notes and bibliography aggiornata). Campobasso.

- Sammartino, A. (2004), Grammatica della lingua croatomolisana, Fondazione "Agostina Piccoli", Montemitro – Profil international, Zagreb.

- Žanić, Ivo, Nemojte zabit naš lipi jezik!, Nedjeljna Dalmacija, Split, (18. marzo 1984).

External links

- Porijeklo prezimena o Moliski hrvati u Mundimitru/Origins of surnames of Croats in Mundimitar

- UNESCO Red Book on endangered languages and dialects: Europe

- Schede sulle minoranze tutelate dalla legge 482/1999 Minority languages in Italy (site of University in Udine, in Italian)

- Le Croate en Italie

- Molisian Slavic at the University of Konstanz (Germany)

- Download of the Italian Version (1997 © Walter Breu) of Milan Rešetar's Book (1911)

- (in Croatian) Vjesnik Josip Lisac: Monumentalni rječnik moliških Hrvata, Jan 9 2001

- (in German) Autonome Region Trentino-Südtirol Sprachminderheiten in Italien

- (in German) CGH - Gradišćansko-hrvatski Centar - Burgenländisch-kroatisches Zentrum Wörterbuch der Molisekroaten (Italien) wurde Donnerstag in Wien vorgestellt

- Lisac, Josip (2008). "Moliškohrvatski govori i novoštokavski ikavski dijalekt". Kolo (in Serbo-Croatian) (3–04).

- Vijenac 186/2001 Posebnost moliške jezične baštine - Dizionario dell'idioma croato-molisano di Montemitro — Rječnik moliškohrvatskog govora Mundimitra predstavljen